Scent of Musk: The Woman Who Can Smell Parkinson’s

HEALTH, 18 Nov 2019

Timofey Neshitov and Daniel Etter – Der Spiegel

So far, no cure has been found for Parkinson’s. It is only possible to treat the symptoms. But a nurse in Scotland can smell the disease before it is diagnosed, and researchers are hoping she can help on the search for a breakthrough.

12 Nov 2019 – On St. Andrews beach on Scotland’s east coast, you might run across a solitary woman on occasion, walking close to the water where the sand is wet and firm. The North Sea wind blows her gray hair over her ears as the woman closes her eyes and holds her nose into the wind. Her nose quivers and lifts, as though she’s about to sneeze.

The woman’s name is Joy Milne. She spent 26 years working as a nurse, raised three sons and cared for her ailing husband. Now, she is widowed. She spends her time traveling and enjoys taking long walks. She is 69 years old.

Her nose is a bit crooked perhaps, neither particularly big nor particularly small, and when she takes her glasses off, which she does to look out at the sea, you can see two dimples where they usually rest. But Milne’s nose is special: She has a much better sense of smell than most people.

She can smell coffee even before she opens the door of a café and registers the scent of her grandchildren before she wraps them up in a hug. But she can also smell things during the day that she doesn’t necessarily want to smell.

Exhaust fumes, butcher shops, perfume stores, the air in airplane cabins: Joy Milne’s nose runs and bleeds when the world around her stinks. Not only that, but unpleasant odors make her cold. Her escape is the North Sea.

The scientific term for her extremely acute sense of smell is hyperosmia, from the Greek word “osme,” meaning “odor.” It is a condition associated with epilepsy, psychosis and pregnancy, but Milne has had an elevated sense of smell since childhood. Of herself, she says: “When it comes to my sense of smell, I’m somewhere between a person and a dog.”

Something Monumental

For the last several years, scientists have taken an acute interest in her nose. Milne, after all, is also able to smell diseases. People with Alzheimer’s smell to her like rye bread, diabetes like nail polish, cancer like mushrooms and tuberculosis like damp cardboard. Having provided care to thousands of sick people in her life, she has had plenty of contact with various illnesses. Milne, though, is most familiar with the smell of Parkinson’s. It’s the disease that killed her husband Leslie and his mother, who she also cared for during her illness.

Every few weeks, she shaves the tiny hairs off her upper lip that disturb her sense of smell, jumps into her white Honda Jazz and drives from her home in the Scottish town of Perth, where she lives in a small house with a garden, to Manchester. The drive takes five to six hours, and each time Milne passes through the revolving door at the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology, located on 131 Princess Street, she feels as though she is part of something monumental.

Parkinson’s has been around from time immemorial, with an ancient Egyptian papyrus from the 12th century B.C. describing the suffering of a drooling ruler. But there is still no cure. Nobody even knows how exactly the disease originates.

Researchers recently began warning of a “Parkinson’s pandemic,” saying that the number of patients worldwide will have doubled to around 14 million by 2040. Life expectancy is on the rise and along with it, so too is the risk of coming down with Parkinson’s.

The disease kills brain cells, and patients gradually lose control of their own bodies, their movements and their speech. It is a long, slow slide.

The last three nights before her husband died, Milne lay next to him in the dark and spoke with him, saying they spoke more openly than at any time during their 42 years of marriage. Les, as she called him, apologized to her for what the illness had made of him.

Enemy in the Brain

Evidence suggests that the enemy in the brain is called alpha-synuclein, a protein that for unknown reasons becomes destructive in Parkinson’s patients. Normally, alpha-synuclein regulates dopamine production, and without dopamine, a person likely wouldn’t even be able to lift a coffee cup: The signal from the brain would never reach the hand.

In Parkinson’s patients, though, the protein apparently begins killing precisely those nerve cells that produce dopamine. The process takes place in the midbrain, an area known as the substantia nigra, or black substance. It is a darker color than the rest of the brain and in cranial cross-sections, it looks not unlike a black ribbon around a brightly colored hat. Parkinson’s nibbles its way forward in hiding — until the motoric symptoms begin appearing: slow movement, tremors, muscle stiffness. By the time a doctor is able to diagnose the disease, between 50 and 70 percent of the cells have already been destroyed.

Ever since the British doctor James Parkinson published his “Essay on the Shaking Palsy” in 1817, generations of patients have had the same experience: “So slight and nearly imperceptible are the first inroads of this malady,” wrote Parkinson, “and so extremely slow its progress, that it rarely happens, that the patient can form any recollection of the precise period of its commencement.”

In Manchester, a team of researchers is exploring the question as to whether it might be possible to diagnose Parkinson’s at an earlier stage before clear symptoms begin appearing. Pharmaceutical companies have spent years developing medicines, but what good are even the best drugs if they can only be prescribed after the brain cells have already been destroyed?

‘A Strong, Masculine, Musky Smell’

The team in Manchester is led by Perdita Barran, a woman who likes to wear jeans and sneakers, with her sunglasses pushed up into her hair. She could be Joy Milne’s daughter. When Milne comes to Manchester, she spends the night at Barran’s home.

Barran is a chemist, not a Parkinson’s researcher, but ever since Milne told medical professionals eight years ago that she is able to smell Parkinson’s, Barran has spent quite a bit of her time on the disease.

Milne claims to be able to smell Parkinson’s in the disease’s early stages and Barran is hoping to develop an early-stage diagnostic test with Milne’s help. The project is called NoseToDiagnose.

Odors are made up of molecules and molecules can be measured, heated and accelerated in tubes. In Manchester, Barran is trying to teach a machine to smell what Joy Milne is able to smell. But what exactly does Joy Milne smell? She didn’t know herself for quite some time.

For many years, she loved Leslie’s bodily odor, describing it as “a strong, masculine, musky smell.” Joy and Leslie Milne had their first, somewhat awkward discussion about body odor in 1981. Les was in his early 30s at the time, a successful anesthesiologist and head physician at a large hospital. One evening when he came home from work, Milne recalls, he smelled like a teenager who hadn’t washed his PE clothes in a while. You should shower more often, she told him. Come to bed, he answered, let’s do the crossword.

Les and Joy first met at school in the coastal city of Dundee, where the River Tay flows into the North Sea. She was 16 and he was 17, the captain of the water polo team. Joy had planned to move to Paris to study French, but because of Les, she stayed in Dundee.

The town smelled of jute back then, with Dundee being Britain’s largest grower of the plant, which is used to produce burlap and rope. Milne likes to take visitors to the top of Law Hill, a green, 170-meter (560-foot) high hill in Dundee with a view of the Tay. “Les and I came up here often,” she says. “Now, it smells of cowslip.”

Deep Purple

When Milne closes her eyes, she smells in color. If she puts a flower up to her nose, a “kaleidoscope,” as she puts it, begins spinning in her head. The medical term for this overlapping of sensory perception is synesthesia, and the color of the scent rarely has anything to do with the color of the object in question. Coffee smells “swirly gray” to her, while the smell of the North Sea is emerald green.

People, too, have colors. Dr. Perdita Barran in Manchester — Milne calls her Perdi — smells green to her, sometimes orange, going on red when Perdi laughs. Les, she says, was “deep purple.”

She smelled her Les in the same way that other people might gaze at a painting or listen to a symphony, though Les himself could smell nothing. He lost his sense of smell in his late 20s. Not everyone who loses their sense of smell, of course, will later be diagnosed with Parkinson’s. A head injury, tumors or a heavy cold can also weaken the sense of smell. But those who come down with Parkinson’s usually can no longer rely on their sense of smell. Today, it is considered an early symptom of Parkinson’s.

Another warning sign that they knew nothing about was bouts of constipation. Milne would cook vegetable stew for her husband to provide him relief.

He also had a restless sleep, dreaming of hunting excursions, shooting at blackberry bushes in his sleep, startling awake and pointing his imaginary weapon at his wife. One time, he lost a tooth crown. Difficulty sleeping, as she now knows today, is also a possible symptom.

What happens in the body of a Parkinson’s patient before diagnosis is different from person to person, depending on genetics, on nutrition and on whether and how much one exercises. Joy Milne, though, now believes that much of what transformed her Les into a different Les was the result of Parkinson’s. The halitosis he began developing in his 30s, the earwax on the pillow. The oily skin on his back and face. His complaints that food tasted bland. At the time, of course, neither of them was thinking about Parkinson’s. Les would clean his ears, brush his teeth and add increasing amounts of salt and pepper to his food.

The two of them had three children.

Irreversible at Age 40

According to one hypothesis, Parkinson’s doesn’t start in the brain, but in the stomach. The theory holds that alpha-synuclein mutates in the bowels and makes its way to the brain via the vagus nerve. The manner in which the protein then settles in the brain was described by the German anatomist Heiko Braak. In 2003, 12 years before Leslie Milne died, Braak published his six-stage model, a theory based on the dissection of hundreds of brains.

In the first stage, the vagus nerve — the 10th cranial nerve, which controls most of our internal organs — is afflicted in the brainstem. This is where the first aggregates appear, and it is from here that the illness spreads via the brainstem into the entire brain. The dopamine-producing substantia nigra is only afflicted in stage three. And that stage is the critical one.

Heiko Braak wrote: “Were it possible to diagnose PD already in the early, presymptomatic stages 1 or 2, and were a causal therapy to become available, the subsequent destruction of the substantia nigra could be prevented.”

For Leslie Milne, the process likely became irreversible as he approached the age of 40.

The strange smell for which Joy had no explanation grew stronger and became creamier, fattier. She had stopped mentioning it to Les. He also began suffering from erectile dysfunction.

From that point on, there were essentially two Leslies. The one was attentive, hard-working and an excellent father. The other was moody, distant and weak. His bodily odor became increasingly foreign to Joy, with his nice deep purple growing increasingly brown.

Illnesses affect metabolism. Even Hippocrates and Avicenna used their noses to make diagnoses. The stool of cholera patients has a fishy odor, the urine of those suffering from diabetes smells sweet. When Milne tries to capture the smell of Parkinson’s in words, she has to think for a bit. “Musky,” she says. “Seabum musky.”

Relying on Comparisons

Musk, though, is a sought-after scent, the basis for many perfumes. Didn’t she use that word to describe her husband’s body odor prior to the illness?

Milne promises to think about it a bit more. It’s not easy to describe odors to people who are unable to smell them. That difficulty has to do with the human body’s complex olfactory system, in contrast to, for example, our sense of taste. Humans can only taste sweet, bitter, salty, sour and umami (the taste of meat broth). Our noses, by contrast, can pick up approximately 400 different odors, as opposed to the 800 dogs can smell. Because our vocabularies don’t have the necessary adjectives for those odors, we rely on comparisons instead.

Our scent receptors are located on the mucous membrane inside the nasal cavity. They are protein compounds that are each responsible for only a single odor molecule and they become active when their molecule comes through the nose and binds perfectly. Odorant molecules come in different shapes and sizes and the entire system functions according to the lock-and-key principle.

Can Joy Milne Help Find a Cure?

Around four years before his diagnosis, Leslie Milne’s right hand began to tremble. He initially tried to hide the affliction from his wife by keeping his hand in his pocket, but his colleagues noticed and thought that he was drinking too much. When Joy noticed as well, her first thought was that he had a brain tumor. On the day before his 45th birthday, she took him to the doctor who diagnosed Parkinson’s.

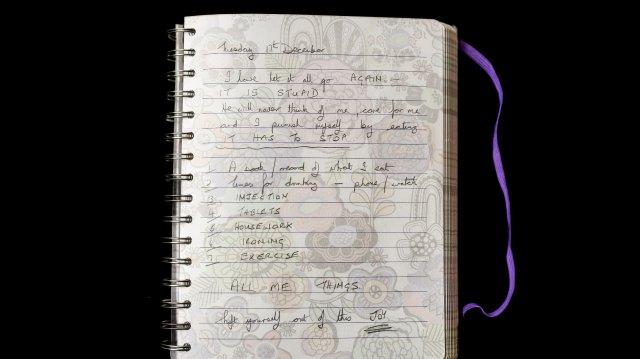

The Milnes knew that things would get worse, but at least they now knew what they were dealing with. Joy Milne began keeping a journal.

In the times of James Parkinson, people with motoric symptoms tended to survive for only a few years. “As the debility increases and the influence of the will over the muscles fades away, the tremulous agitation becomes more vehement,” Parkinson wrote in 1817. “It now seldom leaves him for a moment; but even when exhausted nature seizes a small portion of sleep, the motion becomes so violent as not only to shake the bed-hangings, but even the floor and sashes of the room. (…) The urine and faeces are passed involuntarily; and at the last, constant sleepiness, with slight delirium, and other marks of extreme exhaustion, announce the wished-for release.”

Myriad Side Effects

By the time Leslie Milne received his diagnosis in 1994, doctors had learned how to control many symptoms of Parkinson’s. The most important drug was and is Levodopa, an amino acid that is taken in tablet or capsule form and it is transformed into dopamine in the brain. There are also synthetic preparations that slow the destruction of dopamine and others which mimic the effects of dopamine.

With treatment, Leslie Milne’s hand ceased trembling, he was able to drive his Jaguar again and he could even laugh at his alter-ego, the unpredictable Les over whom he now had a bit more control. He went on to work an additional five years as an anesthesiologist. But the pills did not restore his bodily odor. Les smelled less and less like Les.

The longer you take Parkinson’s medication, the more likely it becomes that you will begin to experience side effects. Leslie Milne endured nausea and dizziness and he grew depressive. Some patients suffer from dyskinesia, a disorder that involves involuntary, uncontrolled movements of the body. Others become addicted to gambling or shopping, while still others may experience psychotic hallucinations or become obtrusive.

On his 50th birthday, Les showed up to his own party wearing underwear printed with the Scottish flag. He wasn’t wearing trousers. He mixed himself a Bacardi & cola and sat down on the lap of a female colleague.

One night, he shoved his wife out of bed and stared at her as though he were gripped by a hallucination. He hit her in the chest and arms and then went back to sleep.

The next morning, he cried. Joy Milne stayed home for two days, her chest covered in bruises. At work, she lied that she had been in a car accident.

Ultimately, Leslie Milne quit his job, sold his Jaguar and got a battery-powered buggy. At the time, the Milnes were living in Macclesfield, just south of Manchester, and in spring 2009, they moved back to Scotland and bought a house in Perth, not far from Dundee.

One afternoon, Joy Milne accompanied her husband to an event in the community center across from the church where a social worker was scheduled to talk about the benefits available to Parkinson’s patients. When they arrived, around two dozen patients were already seated in the room. And every single one of them smelled like Les.

‘We Have to Be Sure’

Thirty years after she had told her husband that he smelled funny, 15 years after his diagnosis, she finally understood what she had been smelling that entire time.

Once they got back home, she told Les of her discovery. “We have to go back again,” he said. “We have to be sure.”

They visited a second event in the community center and went to PD meetings in Inverness, Aberdeen and Fife. Before long, Joy Milne no longer had any doubts about her ability to smell Parkinson’s. But who should she turn to?

At one Parkinson’s event, she got to know Tilo Kunath, a team leader at the Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. Kunath’s expertise is stem cells and Joy Milne asked him: “Why don’t we use the smell of Parkinson’s to diagnose it earlier?” Kunath listened politely and asked if she was perhaps referring to the loss of the sense of smell experienced by patients.

After that encounter, Joy Milne didn’t reach out to any more researchers, instead focusing her energies on caring for Les. He had begun suffering from dementia and would forget to take his medication. Toward the end, he was taking 19 pills each day.

To compensate for his lack of dopamine, Les bought 50 pounds worth of chocolate, sat down in a white recliner and listened to Dolly Parton.

He also signed a DNR order: Do Not Resuscitate. And when Joy Milne smelled him, all she could smell anymore was Parkinson’s. Chestnut brown.

As the disease progressed, Les would prop himself up on a chair to pull weeds in the driveway and their sons and grandchildren began coming by more often to visit. In April 2013, they took their final vacation, visiting Joy’s sister in Dubai. On the flight, Les locked himself in the lavatory and was unable to get the door open again.

Several months after her visit to Edinburgh, Tilo Kunath got in touch with Joy Milne. He asked her if she could smell a few T-shirts for him.

A Cup of Tea

She was presented with 12 T-shirts, six of them having been worn by Parkinson’s patients and six by healthy people. Each T-shirt was cut into two pieces. Joy Milne was able to correctly reassemble the 24 pieces, and then she was asked to identify which of the T-shirts smelled of Parkinson’s. She identified seven.

Ninety-two percent accuracy. Kunath told Milne of an acquaintance of his in Manchester, the chemist Perdita Barran, who worked with odor molecules in her laboratory. Several months later, the seventh test subject whose T-shirt Milne had identified as smelling of Parkinson’s got in touch. He, too, had since been diagnosed with the disease.

On the morning of June 2, 2015, Joy Milne said to her husband: “Les, I’ll make us some tea.” Les was suffering from a urinary tract infection and he was to be taken to hospital that day. He was afraid that he wouldn’t survive the operation. He said: “A tea would be nice.”

From the kitchen, she heard as he stood up from his armchair and fell over. She tried to resuscitate him, but Leslie Milne died that afternoon in the hospital. Many players from the Dundee water polo team came to his funeral.

This March, a study appeared in the journal of the American Chemical Society that proved that the smell of Parkinson’s has its own molecular signature. Joy Milne’s name was listed as one of the study’s 12 authors.

Chemists describe scents by naming their molecules. With Parkinson’s, the odor apparently has to do with four organic compounds: perillaldehyde, hippuric acid, eicosane and octadecanal. It is primarily these four compounds that Joy Milne is smelling when she smells Parkinson’s.

For one experiment in Manchester, sebum samples were taken from the upper backs of test participants. The samples were heated and the molecules thus released were separated, before being conveyed through a tube to Milne’s nose and simultaneously analyzed by a device. Milne would push a button as soon as she detected the Parkinson’s smell, thus helping the researchers determine which compounds were relevant.

The team in Manchester is hoping that the Parkinson’s test will ultimately take just two minutes: The doctor will take a sebum sample from a patient’s upper back using a cotton swab, transfer the sample to a strip of paper and insert the strip into a box, a so-called electronic nose. The box is to cost around 15,000 euros.

Back in the Lab

Joy Milne says that her husband smelled differently 10 years before his diagnosis than he did three years before his diagnosis. So in July, she was again with Perdita Barran in Manchester, sniffing prodromal samples from a clinic in Innsbruck. Prodromal patients are those who have not yet developed motoric symptoms but who complain of constipation or the loss of their sense of smell. Is it possible to train the e-nose to recognize these stages as well?

At lunchtime, Milne and Barran went for a meal across from the institute. When Milne stumbled while crossing the street, Barran immediately moved to keep her from falling. “We should get your nose insured,” she said.

The plan calls for NoseToDiagnose test be finished in 2022.

In June, Joy Milne traveled to the World Parkinson’s Congress in Kyoto. She attended focus groups for women and Parkinson’s and listened to patients discuss sexuality after a Parkinson’s diagnosis. Others talked about coffee and Parkinson’s in addition to smoking and Parkinson’s. She learned that caffeine and nicotine may actually help ward off the disease.

Milne also told the story of her nose, though most participants already knew of her. Milne speaks frequently at congresses, is active on Twitter, has given interviews to the BBC and was the subject of an article in the magazine New Scientist. She has become something of a celebrity in Parkinson’s research, without actually being a scientist herself. At every panel and during every coffee break, she was approached by doctors and patients alike. Keep going Joy!, they would tell her. You’re our great hope!

Leslie Milne had also hoped for a miracle cure. Yet even if the early diagnostic test becomes a reality, it won’t help patients who have already been diagnosed. It is those who don’t yet suspect that they are infected for whom Joy Milne offers the most hope.

And she smells them everywhere: in the line at the supermarket, at the swimming pool, in the airport. But she never approaches them. “When someone is told, you have Parkinson’s,” she says, “I don’t want them to hear it from Joy Milne. They should hear it from their doctor.”

No Cure Yet

In Kyoto, Milne filled several notebooks, jotting down information about deep brain stimulation, gene therapy and skin pathology experienced by Parkinson’s patients. She had flown to Japan because she hoped to learn about the kinds of breakthroughs Parkinson’s research might make with the help of her nose. On the first day of the conference, a researcher from Michigan spoke about new therapies and Joy Milne approached the microphone to ask a simple question: “How are you preparing for the eventuality that we can identify Parkinson’s at a much earlier stage?”

The professor didn’t understand the question at first. He spoke of how well the symptoms could be treated — until Milne interrupted him. Ultimately, the professor admitted that scientists hadn’t yet come up with a way to cure Parkinson’s patients.

The nurse who spent her career bandaging wounds, taking people’s temperature and emptying chamber pots is used to helping people, not to waiting. And Milne was disappointed with the current state of the research and with the researchers themselves, who she believes don’t talk to each other enough. She found herself wondering why she got involved at all. What good is the most sensitive nose in the world if nothing is made of its abilities?

In the night before Leslie died, Joy promised him that she would never give up. That she would do all she could so that no other couple would have to experience what they had experienced.

‘Like Going on a Trip’

After his death, she sold their home and moved into a smaller house a few streets away. In her garden she grows roses, garlic and a Japanese maple. “Each time I step into my garden, it’s like going on a trip,” she says.

She often sits there with her friends Betty and Rena. They met each other at a Parkinson’s event back when their husbands were still alive. Rena’s husband died first, followed 18 months later by Les. Betty’s husband passed away five weeks later.

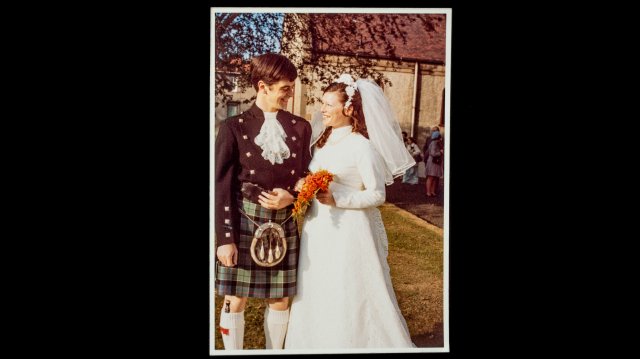

A wedding picture is on display on a chest of drawers in Milne’s bedroom. Leslie is wearing a kilt and Joy has long, dark curls. On a windowsill in the living room sits Toothless, the dragon from the 2010 film “How to Train Your Dragon,” a movie that Les had liked so much. Beneath the sill is a green, plastic urn.

“You get to come out today,” Milne says, placing the urn in the middle of the room.

She gave Les’s white recliner to her son David. “I can’t sit in it,” she says. “The thing smells of Parkinson’s.”

Months later on the telephone, Joy Milne says: “Now I know. It is musk, but a different kind of musk. It’s like with milk when it goes sour: It’s still milk, but something different at the same time.”

Tags: Health, Mental Health, Parkinson's, Research, Science and Medicine

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

In February last year, I was diagnosed of PARKINSON DISEASE. I started out taking only Azilect, then Mirapex and sinemet as the disease progressed but didn’t help much. In July, I started on PARKINSON DISEASE TREATMENT PROTOCOL from Herbal Health Point (ww w. herbalhealthpoint. c om). One month into the treatment, I made a significant recovery. After I completed the recommended treatment, almost all my symptoms were gone, wonderful improvement with my movement and tremors