A Physics of Peace

SCIENCE - SPIRITUALITY, 4 Nov 2013

Prof. Victor Mansfield – TRANSCEND Media Service

Nonlocality, Emptiness and Compassion

Middle Way Buddhism describes a dynamic synergy between its primary pillars of thought: emptiness and compassion. When we understand and experience our deepest, fundamental nature as empty and as interdependent intersections in this vast web of the universe, a natural tendency for compassionate action arises.

Likewise, when we open ourselves up to the suffering of others, our compassion ignites and this in turn deepens our realization of emptiness and our interconnectedness with the world and all of life. Consequently, emptiness and compassion strengthen each other and together they culminate in humane wisdom.

There is an extraordinary precise resonance between emptiness and quantum nonlocality, the most important finding at the conceptual foundations of modern physics. Since our everyday worldview—including our comprehensive interpretation of the universe, ourselves, and how we and the universe interrelate—influences our action then our gaining a greater appreciation for these parallel associations will encourage universal compassion. In this way, modern physics leads us toward peace and love. This is very much in harmony with Buddhism’s Middle Way. Moreover, a feeling connection towards the suffering of others will naturally lead to a deeper appreciation for the interdependence mirrored in quantum mechanics and emptiness. In this way, love then leads to knowledge.

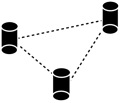

Let us begin with classical or Newtonian physics, which unfortunately continues to dominate our modern worldview. Newton envisioned the universe as built from independently or inherently existent point particles. He understood separate entities as existing in their own right and only secondarily do entities come together to build arbitrary complex structures. Figure 1 (left) illustrates this classical view of entities regardless of whether they are atomic particles or human beings. In the diagram, the entities are substantial things with the solidity of iron posts. The posts’ relationships to each other are noted by dashed lines because in the classical view these relationships are less real and less substantial than the posts themselves. If classical particles could speak they would say something like, “My independent existence is primary. My relationships to other objects are secondary.”

Quantum mechanics is undeniably the best theory in the history of science. Despite that, its findings are much less influential than they should be for shaping our modern worldview. However, during the last several decades, quantum mechanics has revealed that the relationships between quantum entities are often more important, even more real, than is their isolated existence as distinct, separate entities.

Figure 2 (right) illustrates the quantum mechanical view. Here the objects are represented with dashed lines and the connecting lines are solid. This illustrates that the relationships are more fundamental than the objects are alone in isolation.

In fact, an object’s existence depends directly upon its relationship to other objects. If quantum particles could speak they would say, “I exist in a well-defined way because of my relationship to other particles. I have no independent existence.”

In fact, an object’s existence depends directly upon its relationship to other objects. If quantum particles could speak they would say, “I exist in a well-defined way because of my relationship to other particles. I have no independent existence.”

Physicists rarely discuss how physics shapes our worldview and influences our culture. A notable exception is the late David Bohm, internationally known for his important contributions on the foundations of quantum mechanics. Bohm writes:

It is proposed that the widespread and pervasive distinctions between people (race, nation, family, profession, etc.), which are now preventing mankind from working together for the common good, and indeed, even for survival, have one of the key factors of their origin in a kind of thought that treats things as inherently divided, disconnected, and “broken up” into yet smaller constituent parts. Each part is considered to be essentially independent and self-existent.1

Quantum nonlocality—the inability to localize a particle in a finite region of space—differs radically from the assertion that “each part is essentially independent and self-existent.” The most penetrating understanding of quantum nonlocality comes from the celebrated Bell’s Inequalities,2 which analyze correlated pairs of particles. The term “correlation” here is used in the sense that two gloves or two shoes comprising a pair are correlated. This analysis of Bell’s Inequality is independent of the current formulation of quantum mechanics and therefore anything that might eventually replace quantum mechanics in the future must embody this principle of nonlocality. Nonlocality is not an artifact of quantum mechanics but a fundamental property of nature.

The Bell Inequality analysis has its origin in the famous paper by Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen3 (EPR), which considered correlations between pairs of particles that are widely separated spatially. Although Einstein pioneered quantum mechanics, he was never happy with the theory. From the 1920’s to 1935, when EPR was published, he engaged in a number of debates with the physicist Niels Bohr about the conceptual foundations of quantum mechanics.4 Many physicists consider these Einstein-Bohr debates to be the most thrilling and important discussions in science, on a par with the debate that raged around Galileo over the structure of the solar system.

Despite the decades-long running disagreements between Bohr and Einstein about physics’ fundamental principles, they always shared the greatest respect and affection for each other. For example, after their first meeting in April 1920, Einstein wrote Bohr, “Not often in life has a person, by his mere presence, given me such joy as you did. I am now studying your great papers and in so doing—especially when I get stuck somewhere—I have the pleasure of seeing your youthful face before me, smiling and explaining. I have learned much from you, especially also about your attitude regarding scientific matters.” Bohr then replied, “To me it was one of the greatest experiences ever to meet and talk with you. I cannot express how grateful I am for all the friendliness with which you met me on my visit to Berlin. You cannot know how great a stimulus it was for me to have the long hoped for opportunity to hear your views on the questions that have occupied me. I shall never forget our talks.”5

We can go right to the heart of the controversy by examining Einstein’s most explicit formulation of his position. Here we see Einstein’s commitment to the classical view in Figure 1.

If one asks what is the characteristic of the realm of physical ideas independently of the quantum-theory, then above all the following attracts our attention: the concepts of physics refer to a real external world, i.e., ideas are posited of things that claim a “real existence” independent of the perceiving subject (bodies, fields, etc.) . . . it is characteristic of these things that they are conceived of as being arranged in a space-time continuum. Further, it appears to be essential for this arrangement of things introduced in physics that, at a specific time, these things claim an existence independent of one another, in so far as these things “lie in different parts of space.” Without such an assumption of the mutually independent existence (the “being-thus”) of spatially distant things, an assumption which originates in everyday thought, physical thought in the sense familiar to us would not be possible. Nor does one see how physical laws could be formulated and tested without such a clean separation. Field theory [the theory of electromagnetic or gravitational fields, for example] has carried out this principle to the extreme, in that it localizes within infinitely small (four-dimensional) space-elements the elementary things existing independently of one another that it takes as basic, as well as the elementary laws it postulates for them.

For the relative independence of spatially distant things (A and B), this idea is characteristic: an external influence on A has no immediate effect on B; this is known as the “principle of local action,” which is applied consistently only in field theory.6

What Einstein means by “local action” is that the velocity of light is the maximum transmission speed for any information or physical effect to occur. Since light speed is finite, there can be “no immediate effect” of a particle in region A on another particle in region B, or vice versa. Therefore, the EPR/Bell experiments use locality to isolate each particle in the pair.

Einstein’s reference to “mutually independent existence of spatially distant things” is also called Einstein Separability. Objects separated in space and free from any interaction with other objects must exist independently or have well-defined, intrinsic properties. Relationships between objects are then built upon this fundamental independent existence; however, the relationships themselves in this view are less fundamental than the “mutually independent existence” of the related entities.

Einstein believes the separability principle “originates in everyday thought.” Now for the vast majority of people, we usually believe that objects, free of interaction with other objects, have an independent existence. This seems like an obvious truth for us and so it was for Einstein. If this “mutually independent existence” were absent then “physical thought in the sense familiar to us would not be possible.” In addition, Einstein claims that things have a “‘real existence’ independent of the perceiving subject.” Briefly, this means he believes objects have two essential properties: first, they have mutually independent existence and, second, they are independent of our knowing.

Einstein’s two assumptions are precisely a belief in independent or inherent existence, which is exactly what Middle Way Buddhist emptiness denies for all subjects and objects. Einstein is doing us a favor by carefully defining specifically what emptiness denies: inherent or independent existence.

Deriving the Bell Inequalities only requires assuming locality and mutually independent existence. Physicists are very confident that nature embodies locality. Therefore, the experimental violation of the Inequalities—which today students can demonstrate in an undergraduate lab—conclusively shows that the correlated particles do not have mutually independent existence. Instead, as quantum mechanics implies, nature is nonlocally interconnected. So despite Einstein’s objections, what happens in region A is instantaneously influenced by what happens in region B, regardless of the distance between A and B.

The Inequalities’ analysis, however, does not replace our erroneous view of objects as having independent existence with some new principle. Just as in traditional Buddhist arguments to posit and support emptiness, there is a massive negation without invoking a deeper reality beyond nonlocality.

The correlated particles are instantaneously interconnected in ways inconceivable if we were to rely only on the ideas from classical physics. We are so used to conceiving of a world of isolated and independently existing objects that it is difficult to appreciate this rigorous experimental refutation of independent existence. Therefore, we find the very nature of reality demanding a major paradigm shift at the foundations of science and philosophy—one with enormous implications for fields well beyond the boundaries of science and philosophy.

In the David Bohm quote cited above, he suggests that a key factor giving rise to the pervasive strife between peoples and nations is “a kind of thought that treats things as inherently divided, disconnected . . . . [where] each part is considered to be essentially independent and self-existent.” Bohm is identifying the classical view of reality as a cause for conflict whereas we have just seen that quantum nonlocality teaches just the opposite. Let me elaborate by turning to Middle Way Buddhism.

In Middle Way Buddhism, the realization of emptiness—the complete lack of independent existence in all subjects and objects and their profound interdependence with each other and the world—decreases egotism and increases a genuine concern for all of life. If I truly lack independent existence, if my deepest reality is one of mutual dependence upon other life forms and my environment, how can I be concerned with just me? How can I focus only on the needs of simply one intersection, namely myself, among the innumerable dependent relations that define all people and things? Of course, we have no rational justification for our self-centeredness and self-cherishing. Nevertheless, these firmly ingrained tendencies are painfully difficult to uproot.

The greatest obstacle for appreciating emptiness is our inveterate and unconscious belief in the independent or inherent existence of our own egos. Practicing compassion weakens this false belief that blocks the doorway to the wisdom of emptiness. Thus, if we can truly practice compassion, if we can show a genuine concern for both our fellow humans and the environment, then our understanding of emptiness and the implications of its far-reaching interconnectedness with all of life must grow. In this way, the Middle Way’s two pillars have a synergistic relationship and encourage us to be responsible for the welfare of all sentient beings and the environment.

I have always wanted to understand more deeply the connection between compassion and emptiness. I actually wanted to derive compassion from emptiness, to see how it flows logically from the lack of inherent existence, like a result in physics. Perhaps my years of doing theoretical physics predispose me to this approach. Emptiness certainly implies compassion. Nevertheless, it was never satisfying to derive compassion from intellectual analysis alone.

Fortunately, life has shown me a little about approaching compassion through the heart. It has shown me how to take in the pain of other people and thereby make a deep feeling connection to them. When I do so I become more open to them and the reality of their suffering. In this way, instead of approaching compassion through emptiness or nonlocality, I try to open up to the suffering of others and then assimilate my profound interconnections with them. The ultimate goal is to expand this openness so that it includes all suffering beings. Such openness to the suffering of others softens my habitual focus on my ego and its needs. The connection is through the heart not through the head. This leads to feeling a realization of emptiness. I then appreciate how connections to others establish my own identity and how without these relationships there is no me at all. Here is a short personal experience from a couple of years ago to convey what I mean.

The Thief as Guru

I am traveling for several weeks in Europe giving lectures and workshops. Despite the terrific extroversion of such activities, I am enjoying the periods of isolation and introversion that travel provides. I have finished reading the books I brought from home, so in a London airport I purchase Ethics for the New Millennium by the Dalai Lama. Although I have heard all of these ideas before, both through reading and oral instruction, the book’s direct, clear, and simple message inspires me. With a minimum of technical language, the Dalai Lama shows how our happiness and genuine ethics follow from our effort to alleviate suffering. The root of all ethical action must be our sincere effort to reduce suffering. These well-known ideas have been electrifying me for the last couple of days.

After about an hour of reading in the Barcelona airport, I stretch my legs with a walk among the fancy shops. I continue to reflect on these ideas as I return to the departure gate. On my way toward the departing line, I sincerely vow to work more intensely on practicing compassion. I tell myself, “I can surely do much better.”

Suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I see a fearsome fist fight about 20 meters from my departure line. A policeman and another man are furiously pummeling each other. The policeman is on the floor and getting the worst of it. I instantly decide that this is harming the other man even more than the policeman so I sprint to the fight. I grab the man by the shoulders and pull hard, but I cannot separate them. In desperation, I come up behind the man, wrap my right arm over his right shoulder, grasp his left arm, and give a mighty heave. As the two men separate, the man pinned against my chest gives a powerful two-legged thrust to the policeman’s chest knocking off his badge and throwing him flat on his back. The man and I land in a heap with me on my back and him on top of me.

I hug him tightly to my chest, while we struggle awkwardly to a sitting position. He is breathing like a racehorse. His heart is pounding. I feel his beard stubble against my left jaw. Astonishingly, the policeman jumps up and runs to the far end of the terminal and telephones for help. I am very unhappy being left clutching the fighter, but soon other people come to restrain him. I say to him with surprising tenderness, “Just let it go. It is not worth it.” These seem like strangely ineffective words, especially since he is unlikely to understand English. I notice that he is about thirty years old, the same age as my oldest son.

In a few minutes, more police arrive and handcuff the man. I get up from the floor and return to the departure line. My tailbone is sore from landing on it. Somebody hands me the Dalai Lama book that had fallen on the floor early in the struggle. As I walk back to the line I think, “The cop didn’t even say ‘Gracias.’”

Standing in line, a deep sadness overwhelms me. I have to fight the desire to sob uncontrollably. Embarrassed to cry in the departure line, I ask myself, “What is this powerful sadness?” Somebody ahead of me in the line tells me that the policeman caught the man picking somebody’s pocket.

That overwhelming sadness has long mystified me. At first, I thought my sadness was due to the policeman not recognizing or appreciating my effort. “I risked physical harm to minimize the pounding that policeman was taking. I want at least a ‘Thank you.’” Even more, it embarrasses me to confess my desire to be lionized as a hero. Realizing that my motivation was not entirely pure grieves me, especially when in the book that was just inspiring me the Dalai Lama’s writes, “When we give with the underlying motive of inflating the image others have of us—to gain renown and have them think of us as virtuous or holy—we defile the act. In that case, what we are practicing is not generosity but self-aggrandizement.”7

My motivation was not entirely pure, but there surely is more to it. When I clutched that man in my arms, besides feeling his heart beating wildly, his gasping breath, and even the scratch of his whiskers, I also felt his suffering. A genuine tenderness welled up in me towards him. More than physical intimacy, I directly contacted the broken life that led to the event, a brokenness that was likely to continue well after the prison term that was sure to follow. It is one thing to reflect quietly on suffering while reading a book and another to feel it squirming against your body. I did not have to think about nonlocality in quantum mechanics to make a connection with this man. I only had to be open to his suffering. The Dalai Lama writes,

When we enhance our sensitivity toward others’ suffering through deliberately opening ourselves up to it, it is believed that we can gradually extend our compassion to the point where the individual feels so moved by even the subtlest suffering of others that they come to have an overwhelming sense of responsibility toward those others. This causes the one who is compassionate to dedicate themselves entirely to helping others overcome both their suffering and the causes of their suffering. In Tibetan, this ultimate level of attainment is called nying je chenmo, literally “great compassion.”8

I certainly have not attained anything like the advanced level of nying je chenmo, but I have seen how opening, even unwittingly, toward the suffering of others makes me appreciate the profound interconnectedness we all share. Such appreciation through the heart complements the intellectual apprehension of quantum nonlocality and emptiness. That man, accused of being a pickpocket, could have been my son. As much as Einstein and Bohr educated my intellectual understanding, he educated my heart.

____________________________

Victor Mansfield (1941-2008) was Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Colgate University and a student of Tibetan Buddhism. He published widely in physics, astronomy, and several interdisciplinary fields, studied and practiced with teachers in the USA, Europe, and India, and lectured widely in the USA and Europe. In 2008, Professor Mansfield published Tibetan Buddhism and Modern Science, with an introduction by His Holiness the Dali Lama.

Go to Original – sevenpillarshouse.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

SCIENCE - SPIRITUALITY: