Study: Diet, Exercise May Prevent Dementia

HEALTH, 28 Jul 2014

Gary Stix – Scientific American

New research suggests a multi-pronged approach may be most effective in preserving brain health long-term.

In 2010, the National Institutes of Health held a conference to determine what measures, including behavioral steps like exercise and diet, could be taken to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s. A report prepared specifically for that conference by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) made an assessment of the existing evidence for preventive measures. It determined that there was no intervention—whether jogging, the Mediterranean diet or a long list of other factors—for which there was sufficient proof to make any convincing recommendations to physicians or their patients.

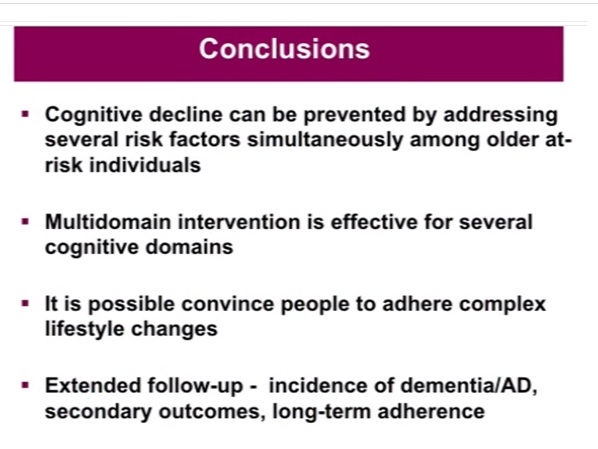

To be able to one day make such recommendations, the report suggested implementing randomized-controlled trials that would address multiple risk factors simultaneously in individuals with a high likelihood of getting the disease. The first results of pursuing this approach are now in—and they offer a sliver of hope in a field that has had little to cheer about in recent years, having experienced one drug failure after another.

Results of the first clinical trial that conforms to AHRQ’s pull-out-all-stops approach were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association’s International Conference in Copenhagen on July 13. The large-scale study of 1260 individuals at risk of cognitive decline showed that study volunteers who rigorously adhered to measures prescribed for diet, exercise, cognitive training, social engagement and management of cardiac risk factors had better results on a battery of tests of cognitive results than did a control group that had received more generic health counseling.

The results on the cognitive test battery for the group with the intensive lifestyle intervention showed a strong signal that this “multidomain” approach was working, reaching a high level of statistical significance. (The “p-value,” used to measure statistical significance, was less than .001, considered highly significant.)

Volunteers for FINGER (the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability), ranged in age from 60 to 77 and were drawn from six Finnish cities. They showed good compliance with the regimen, with only 11 dropouts over the two years the trial has been running. Cognitive improvements in the intervention group were made on all measures surveyed, including memory, planning abilities, and speed of mental processing. Miia Kivipelto, the lead investigator, and a prominent expert on lifestyle factors related to dementia, said at a press briefing: “It’s a proof of concept study giving the first evidence from a large, long-term, multi-domain randomized controlled trial really showing that we can reduce the risk of cognitive impairment in an older at-risk individual.” A seven-year followup study is slated to begin next year.

FINGER’s multi-pronged effort makes sense. Aging is the primary risk factor for Alzheimer’s and the low levels of chronic inflammation and metabolic disruption that set in as a person gets older may interact with certain genes to set in motion the buildup of intra- and extracellular gunk, the plaques and tangles that short out neural circuits and ultimately kill brain cells. Keeping inflammatory molecules, insulin signaling and other toxic processes in check may preserve brain health, at least for a time.

Something like this is needed because the news about drugs for Alzheimer’s has been almost relentlessly bad. The Cleveland Clinic had a study published in early July that showed that 99 percent of all Alzheimer’s drugs failed. At the Copenhagen conference, there was a report of a drug from Roche targeting the toxic amyloid protein fragment that failed to meet its targets of slowing the disease by preserving cognition and ability to function, but seemed to have some benefit in patients with mild Alzheimer’s at highest doses of the drug.

Drugs for Alzheimer’s will ultimately be available, but it’s probably going to take a while. The emphasis in the entire field has shifted to prevention before the first symptoms appear, as researchers have recognized that this may be the only way to stop the disease in its tracks. Administering drugs to people ascertained to carry some risk factors but who are otherwise cognitively healthy are already underway.

Testing a drug’s effect in a healthy person is likely to be a long and arduous process. The level of a toxic protein in the brain might diminish, but it may still be uncertain whether the change in that biological marker has altered the risk that an individual will get Alzheimer’s. A number of drugs targeting the toxic amyloid-beta protein fragment have failed in patients with Alzheimer’s. It may be that they will work in pre-symptomatic patients. Or they may work if combined with other drugs that target other toxic proteins—tau or TDP-43, for instance. And these drugs may need to be paired with others still that protect neurons while the toxic proteins are being cleaned out.

Figuring all this out is going to take a while. Preventing Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia by changing the way you live may turn out to be the best solution until researchers find drugs that can treat the tens of millions worldwide who have received the fateful diagnosis.

________________________________

Gary Stix, a senior editor, commissions, writes, and edits features, news articles and Web blogs for Scientific American. His area of coverage is neuroscience. He also has frequently been the issue or section editor for special issues or reports on topics ranging from nanotechnology to obesity. He has worked for more than 20 years at Scientific American, following three years as a science journalist at IEEE Spectrum, the flagship publication for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. He has an undergraduate degree in journalism from New York University. With his wife, Miriam Lacob, he wrote a general primer on technology called Who Gives a Gigabyte?

Go to Original – scientificamerican.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.