It Is a Long Fight: Lenin in 2015

ACTIVISM, 5 Jan 2015

Alexander Reid Ross - CounterPunch

A Historic Struggle

A strike would ignite another strike. The army would fire on peaceful protestors, killing scores. A general strike would be declared, with infrastructure of popular power blossoming out of new councils comprised of a mixture of political ideologues and working class organizers. Barricades would be built in the streets, and army battalions would mutiny, razing barracks to the ground.

This was the climactic year of 1905, but what laid the roots for this struggle, and how was it eventually, and temporarily, defeated?

The story stretches back a long ways, to the heroic liberals of the early 19th Century who opined sanguinely on the plight of the serfs, and rose up from the upper echelon of the army in attempts to depose the tsar. This era, as Bakunin noted during the next phase of revolutionary tumult, could make reform, not revolution, because it did not emerge from the “people.”

Bakunin was writing in the 1860s, the start of the next, great movement of Russian revolutionism, and his critique landed squarely on the shoulders of the bourgeoisie liberal class which dominated the peasantry even after reforming the law and emancipating the serfs. As radicals from Marx to Bakunin to Tkachev insisted, the emancipation of the peasants could not bring true liberation, because the relations of capitalism over feudalism simply layered a new class onto an old nobility.

From the 1860s until the 1880s, the greatest revolutionary trend in Russia took the form of conspiratorial terror, assassinations, bomb-throwings, and sabotage. It was not until the establishment of greater organizational leadership through various working class associations, as well as the Russian Social Democrat Labor Party by Plekhanov and collaborators, that an organized strategy towards revolution embraced the working class as an instrumental agent in its own future.

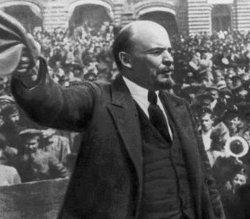

Lenin Emerges

Fighting his way into this movement with a vicious, incisive pen, a man of various pseudonyms proved himself capable of sweeping analyses of agricultural and economic problems, maligning those who disagreed with his essential point of view. His main points were, to put it succinctly, divisive. The peasantry’s ignorance could not be underestimated, this writer, who settled on the nom de guerre of “Lenin” insisted, and the proletariat’s job was to liberate rural life by establishing working class consciousness through peasant councils. As for those who believed in peasant-led revolution, he scoffed in his early, 1893 essay, “Scratch the ‘friend of the people’—we may say, paraphrasing the familiar saying—and you will find a bourgeois.”

“[T]he merging of the democratic activities of the working class with the democratic aspirations of other classes and groups would weaken the democratic movement,” Lenin declares from exile in 1897. “The proletariat must not regard the other classes and parties as ‘one reactionary mass,’” he writes two years later. There are clear, decisive distinctions that separate the peasants from the proletariat, and even there, the rural poor are distinct from the privileged, “enterprising muzhiks” who mark the origins of capitalist development.

But as history began to take a turn into the 20th Century, Lenin would find his doctrine compromised. A split developed within the party organ that he had helped to found, Iskra (Spark), with one side insisting that a more diffuse, autonomous editorial structure be utilized, against Lenin’s strict interpretation of the party platform. As the split deepened, his writings turned with an astonishing transformation, back to his bread-and-butter: legal issues.

The Fight Against the Police State

As a trained lawyer, Lenin’s inward turn marked an important confirmation of external occurrences. By the beginning of the century, the popular uprising against the police and the military could not be ignored. The idea of “a single class struggle of the proletariat,” of which Lenin would write in 1899 would give way somewhat to more open language the next year, when he notes that “[d]uring recent decades, hatred for the police has grown immensely and has become deep-rooted in the hearts of the masses of the common people.” The “net” of law enforcement, Lenin professes, is “all-entangling,” the “canker” is persistent,” and “can only be removed by abolishing the whole system of police tyranny and denial of the people’s rights.”

Through his analysis of the legal code, Lenin’s hatred of absolutism is reinforced, and he proceeds into the 20th Century with a prophetic tone: “the workers are struggling for the interests of the whole people, and when that has been done, the day of the victory of the revolutionary workers’ party over the police state will come with a rapidity exceeding our own anticipation.”

As workers organize throughout Russia into councils to fight the mobilization of the police state, Lenin sees his opportunity. From his 1901 Review of Home Affairs: “Public unrest is growing among the entire people in Russia, among all classes, and it is our duty as revolutionary Social-Democrats to exert every effort to take advantage of this development, in order to explain to the progressive working-class intellectuals what an ally they have in the peasants, in the students, and in the intellectuals generally, and to teach them how to take advantage of the flashes of social protest that break out, now in one place, now in another.”

Finally, the turning point: Lenin releases What Is to Be Done?, arguably his masterpiece, in 1902, divorcing himself from the school of “tactics-as-process,” and hardening his stance on the strategic fight against the police state. Unifying the Party under a consolidated vision with “the will of an army that follows and at the same time directs its general staff” becomes crucial. But he envisions that the first step on the way to abolishing the autocracy is to legalize aspects of the movement forced underground by state repression; he has no clue of what is to come, and it shows.

Bringing the People Together

Even 1902, just three years before the upheavals, Lenin worries about distinguishing the reactionary peasants from the radicals who understand proletarian consciousness—a problem that will seem to evaporate as the militant events of 1905 begin to unfold. As the strikes sweep through Russia, towns raise the red flag, mutinies strike Sevastopol, and generalized insurrection emanates from St. Petersburg, Lenin identifies the peasantry as the “tens of millions… The ‘people’ par excellence,” but also “the unstable elements of the struggle.” His ultimate aim, he insists, is that ““all power—wholly, completely and indivisibly—[rests] in the hands of the whole people,” and to do that, the radical democrats of both bourgeois and peasant classes must be united.

As the reactionary, paramilitary movement of the “Black Hundreds” set in to fight the peasants and workers, Lenin insists that “only an armed uprising” can instill revolutionary order. “[T]he revolutionary army and the revolutionary government are ‘organisms’ of so high a type, they demand… a civic consciousness so developed, that it would be a mistake to expect a simple, immediate, and perfect fulfillment of these tasks from the outset,” he writes, marking the first instance where the Bolsheviks begin to agitate within the Russian army while creating disciplined self-defense groups and openly advocating the arming and training of the people in street “fighting.”

Today, at the end of 2014, we in the US stand on the precipice of a similar event in history. It is, perhaps, a breaking point. The success of the Black Lives Matter protests surrounding police violence has crystalized a sense of integrity within the populace in the same way that the Civil Rights Movement had done in the late-1950s. But this is a long and arduous struggle. With the class analysis brought to the fore through the Occupy movement, we might look to this year’s important protests against consumerism in various malls and Walmarts across the country, and their intersections with the state repression of people of color.

Concluding Thoughts

Is it sensible to try and take Lenin’s intensive strategy to heart, and follow his path to our own 1905? Even the most hardcore Leninist in the USA today will say “absolutely not.” Lenin is seen by his followers as a motivating presence who attempted to consolidate voices towards a universal emancipation from oppression of class, nation, and race.

Of course, his divisiveness and the co-optation of the popular movement towards the aims of vanguardism remain critical points to dismantle the authoritarianism that his legacy has wrought over the world, but assessing Lenin’s strategic deployment of slogans and hegemonic positions as his ideas grew increasingly general during the waves of paroxysms crashing over Russia in 1905 gives us both a chance to see how horizontal movements can catalyze tremendous new flows of energy and how they can be compromised (for instance, the co-optation of the Saint Petersburg Soviet, which was originally radical and anarchist-run).

People of color rising up in the US has brought world-changing results. Their leadership presents the opportunity, not to compromise, misdirect, or co-opt the movement, but to deepen the struggle. The fight against the police state, which opened up even the most hardened rhetoric of Lenin, himself, produces the most revolutionary of circumstances. We must take our lessons from the outcome of 1905, and not waver in defense of egalitarian principles in the struggle for a better world. It is a long fight, but perhaps the most important of all.

_________________________

Alexander Reid Ross is a contributing moderator of the Earth First! Newswire and works for Bark. He is the editor of Grabbing Back: Essays Against the Global Land Grab (AK Press 2014) and a contributor to Life During Wartime (AK Press 2013). This article is also being published at earthfirstjournal.org/newswire.

Go to Original – counterpunch.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.