What Really Happened in the WW-I Christmas Truce of 1914?

HISTORY, 28 Dec 2015

1. A Popular Christmas Story

The Christmas Truce of 1914 is often celebrated as a symbolic moment of peace in an otherwise devastatingly violent war. We may like to believe that for just one day, all across the front, men from both sides emerged from the trenches and met in No Man’s Land to exchange gifts and play football. But first-hand testimonies help us get closer to what really happened.

Along the Western Front, a scattered series of small-scale ceasefires did happen between some German and British forces. But this brief festive reprieve was far from a mass event. Where it didn’t occur, 25 December 1914 was a day of war like any other. Where it did, accounts suggest that men sang carols and in some cases left their trenches and met in No Man’s Land.

However, the motivations for such events were complex – practical as much as ‘magical’ – and this wasn’t the first unofficial truce to take place. Instead, it was to be one of the last.

- ‘Live and Let Live’: Unofficial Truces

By November 1914, it had become clear that the war was not going to be over quickly. As autumn turned to winter, the last of Britain’s professional soldiers, exhausted after months of vicious fighting, settled into the routine of life in the trenches of northern France.

They naturally began to think of enemy soldiers – sometimes a few feet away – doing the same. As a result of this proximity a ‘live and let live’ attitude developed in certain areas of the trench system.

Reciprocal periods of ‘quiet time’ emerged when soldiers tacitly agreed not to shoot at each other. Between battles and out of boredom, soldiers began to banter, even barter for cigarettes, between opposite sides. Informal truces were also agreed and used as an opportunity to recover wounded soldiers, bury the dead and shore up damaged trenches. In many ways, for the last of the professional soldiers, this was all part of the etiquette of war.

However, the High Command feared the longer-term impact of such activity and issued strict orders that officers should be vigilant against this kind of contact – regarding it as treason.

Yet this early on in the war, and across such a large front, these truces were simply a practicality – and certainly not unique to Christmas.

- Call for Peace

The arrival of December 1914 was proof, if any were needed, that the war would not be ‘over by Christmas’. For the men at the front, months of tough fighting were to be followed by a festive period away from home.

Back in Britain, German battleships shelled the coastal towns of Whitby, Hartlepool and Scarborough, killing 122 and injuring 450 civilian men, women and children. On the Western Front, fierce fighting took place in the Ypres Salient, leading to the deaths of many soldiers. It was the recovery and burial of these casualties which gave rise to the practical need for a cessation of fighting at certain areas of the front, like Ploegsteert Wood, which the British soldiers called ‘Plugstreet’.

On 7 December, Pope Benedict XV had proposed a wider official ‘Truce of God’ in which all hostilities would cease over the Christmas period. The authorities rejected the idea but were keen to maintain morale and bring at least some festive cheer to those at the front.

Throughout the month, 460,000 parcels and 2.5 million letters were sent to British soldiers in France. King George V sent a card to every soldier, and his daughter, Princess Mary, lent her name to a fund which sent a small brass box of gifts, including tobacco or writing sets, to serving soldiers. General Haig even records in his diary for 24 December: “Tomorrow being Xmas day, I ordered no reliefs to be carried out, and troops to be given as easy a time as possible”.

The Germans too received small gift boxes – alongside table top Christmas trees and festive wreaths with which to celebrate the season.

- Christmas Eve: Silent Night

By Christmas Eve itself, the damp weather gave way to the cold and a festive frost settled on certain places at the front. As the main night of celebration in Germany, candles and trees went up along parts of the German line.

And as darkness fell, the entrenched German and British soldiers engaged in a carol sing-off.

- Presents, Kick-Abouts and Funerals

Along parts of the front, some men responded to the events of Christmas Eve by tentatively emerging from their trenches into No Man’s Land on Christmas Day. Where it happened, enemy soldiers did indeed meet and spend Christmas together.

Spontaneously, they exchanged gifts and took photos – but it was importantly an opportunity to leave the damp of the trenches and tend to the dead and wounded of No Man’s Land. There wasn’t a single organised football match between German and British sides. There may have been small-scale kick-abouts – but these were just one of many different activities men took the time to enjoy.

Meanwhile, in other places along the front, like Yser, bloody battles took place over the Christmas period and those that dared to come above the parapet were met not by gifts but gunfire. Belgian, Indian and French troops who witnessed episodes of fraternisation were at best puzzled and at worst very angry that British troops were being friendly towards the Germans.

- The Generals’ Reaction

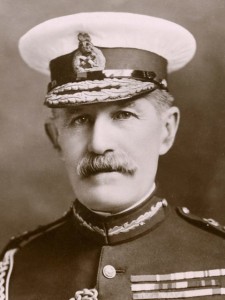

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien – commander of British 2nd Army Corps Expeditionary Force – issued strict warnings to his senior officers about preventing fraternisation with enemy soldiers.

Mary Evans / Pharcide

Reports and photographs of these small-scale unofficial ceasefires reached the papers back home – and the military authorities.

High Command was angry – they feared that men would now question the war, and even mutiny, as a result of fraternising with the enemy that they were meant to defeat. Stricter orders were issued to end such activity – with harsh punishment for any man caught refusing to fight.

The London Rifle Brigade’s War Diary for 2 January 1915 recorded that “informal truces with the enemy were to cease and any officer or [non-commissioned officer] found to having initiated one would be tried by Court Martial.”

As the war continued, brutal developments on the battlefield changed the character of war in 1915. The enemy were further demonised and fraternisation made even less likely.

The small truces of 1914 never happened again. Yet despite the best efforts of the authorities, the story was out there – in the media and in the popular imagination. A story that has been re-told and re-shaped many times in the decades that followed.

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien – commander of British 2nd Army Corps Expeditionary Force – issued strict warnings to his senior officers about preventing fraternisation with enemy soldiers.

7. An Enduring Myth

The few reports of a football match between forces have endured for a century, but what has contributed to the focus on this part of the story?

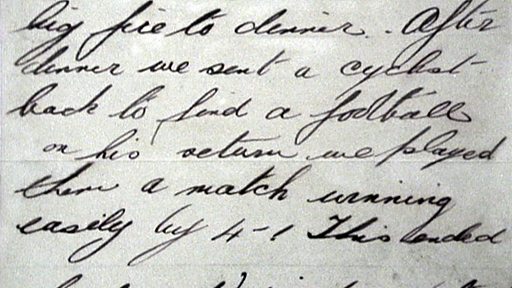

1914- Soldiers’ letters

In one, a soldier wrote: “We sent a cyclist back to find a football, on his return we played them a match winning easily by 4-1!”

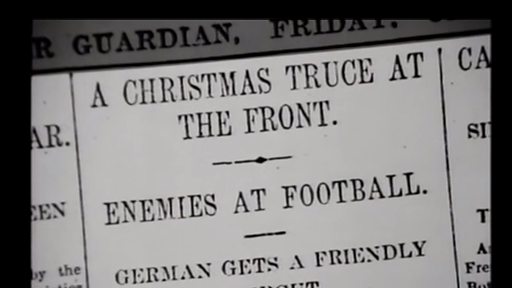

1915: Newspaper reports

After letters arrived home, the press printed their version of events in the New Year – with particular mention to the few reported football matches.

1960s- WW1’s 50th anniversary

Play-turned-film Oh! What A Lovely War dramatises the truce as part of its anti-war narrative. And in the Football World Cup final 1966 England plays Germany.

1980s: Blackadder Goes Forth

The final episode of the 1989 WW1 comedy mentions the football match. Eight years earlier, documentary ‘Peace in No Man’s Land’ reignited interest in the truce.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWF2JBb1bvM

_________________________________

Dan SnowBroadcaster & Historian at BBC.

Photos/Stringer.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.