Saving ‘Natural Resources’ Won’t Save Us

ACTIVISM, 19 Sep 2016

Greg Harman | Deceleration – TRANSCEND Media Service

13 Sep 2016 – For most of middle America—or most of America, actually—protests of any sort demonstrate questionable behavior. People are suddenly “out of their place,” different kinds of people, people made strange by their willingness to do unfamiliar and possibly illegal things to advance their message.

13 Sep 2016 – For most of middle America—or most of America, actually—protests of any sort demonstrate questionable behavior. People are suddenly “out of their place,” different kinds of people, people made strange by their willingness to do unfamiliar and possibly illegal things to advance their message.

They draw attention to themselves, and thereby, they hope, to whatever message is scrawled across their poster paper. They gain attention by pushing boundaries, those that had previously been assumed and invisible, boundary lines of private property (the domain of those who “rightfully” own the land) or public spaces (where traditional, non-confrontational patterns of behavior are preferred).

So right off the baton, the protestor makes the world strange by leveraging a sudden impossible-to-ignore conviction against the otherwise invisible weight of the status quo. While some commentators have suggested that public protest no longer is effective (NPR, 2008), the Keystone XL pipeline outcome seems to seriously undercut that position.

Whether or not they affect change in the short term, those who complicate the world by challenging often hidden authorities expand what people feel permitted to say privately—the nine percent of the 99 percent of Americans who supported the Vietnam War protests but never managed to join one, according to this Gallup polling. Or, perhaps, the slim majority of Americans who supported the right to protest after the invasion of Iraq but remained aloof.

“We’re not protesters. We’re here to defend the land.” Excy Guardado at a Standing Rock solidarity action, San Antonio, Texas.

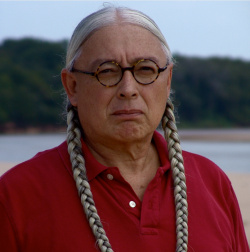

Alvaro Itzli Ramirez. Credit: Greg Harman

Protesting sometimes has a higher purpose than defeating a particular object. Arguing against critiques that the effectiveness of environmental campaigns should be what carbon reductions they directly bring, David Roberts argued post-Keystone that the “other part of transitioning to a new world is contesting the legitimacy of the old one. That means taking assumptions, institutions, and technologies that have a presumptive social warrant — that are assumed necessary, legitimate, and worthwhile by default — and, God help me for using this word, problematizing them.”

So here we are facing an intentional complicating at the standoff at Standing Rock and the appearance of more sustained indigenous-led “land defense” actions in Canada the U.S. That complicating is not only the act of physical resistance, but it is vitally expressed also in the language coming forward, providing a stark break with the way past protests, and past environmental protests, in particular, have been described and described themselves.

“It’s not about natural resources. It’s about Mother Earth,” said Anayanse Garza, co-founder of Vecinos de Mission Trails (of which, full disclosure, my partner is as well), while leading a community discussion about Standing Rock here in San Antonio last week. That assertion represents a cosmovision that while not out of tune with mainstream environmentalism, intentionally distances itself from the language of the past.

The language of resources is directly tied to the colonial and “settler state” outlook that followed new Americans across the country, displacing the original inhabitants in their advance. Settlers were driven to populate and subdue the land. It was their Christian mission. And it’s an outlook that remains, according to Walter R. Echo-Hawk, standing in the way of the creation of a land ethic capable to moving us to the relationships required to stop the destruction of the biosphere.

Deeply embedded “dominionism,” Echo-Hawk, an attorney and Supreme Court Judge of the Pawnee Nation, writes in In The Light of Justice: The Rise of Human Rights in Native America:

“Christianity, religious intolerance, secularism, and scientism are powerful forces. They work to sever ties to the land, because they cannot see the spiritual side of Mother Earth. … They effectively close our eyes to the sacred in our world and act to take God out of nature, even though that is where the Great Spirit abides.

“This is troubling, because the land ethic for our industrialized nation cannot be founded upon science and technology alone, for they caused much of the environmental trouble and lack the tools, knowledge, wisdom, and moral willpower to solve that crisis.”

The language of dominionism continues within environmentalism. Demonstrating how embedded this mindset remains within Western culture, consider that one of the most effective organizations struggling against those forces picking apart the life-sustaining powers of the natural world—the Natural Resources Defense Council—maintains this lingual relic of colonial advancement. This is not to say the organization must immediately change their name and risk the interruption of their hard-won influence, but it should be a point of conversation, as such terminology resists the necessary shift in cosmovision.

The air, the water, soil, sea are not “resources,” which Merriam-Webster defines firstly as “something that a country has and can use to increase its wealth.” They are part of a totality, a living entity, the life given, a relation at the grand scale. Going back to Echo-Hawk: “In primal cosmology, only a thin line exists between humans and the animals and plants that live in tribal habitats—and everything, including the land itself, has a spirit.”

Just as we are advised to move beyond the language of acquisition and extraction (the voice of the negative, that is, a subtracting force), there is another challenge to those reporting on Standing Rock. The word “protestor,” which opened up this essay.

The day after the San Antonio community meeting, Azteca dance troupes held a solidarity action for those at Sacred Stone Camp who are engaged in sustained and direct resistance to the Dakota Access pipeline that would move Bakken shale across the country to a refinery at Nederland, Texas. It was held in front of the Alamo, a potent site for political discussion. A visitor from Connecticut asked a young woman sitting outside the cycling whorl of dancers what the group was protesting.

“We’re not protesters,” Excy Guardado replied. “We’re here to defend the land.”

Here’s another language shift that is not small. The rejection of the term “protester” by those at and supportive of the North Dakota fight is important. Like a rejection of “natural resources,” it seeks to reverse framing of those opposing petro-based development as a negative force—those posed in opposition to the positive forces of development.

In its place, “land defenders” would position protesters as a positive force, pre-dating oil and gas extraction. Land defenders are postured in advance and far beyond the current conflict. They are rooted in land, perhaps the ultimate positive anchor. I don’t know if those who have resisted protesting generally will be swayed by the new language as it begins to root itself in public discussion of the onset of climate change, mining of the overheating oceans, rapid depletion of the forests, and speeding collapse of the planet’s biodiversity, but I know that language has power. And for those already involved in the struggle in whatever capacity, it’s worth paying attention to.

________________________________________

Greg Harman is an independent journalist who has written about environmental health and justice issues since the late 1990s. His work has appeared in the Austin Chronicle, Guardian Sustainable Business, Dallas Morning News, Yes! Magazine, Houston Press, and the Texas Observer, among many others, and been honored by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies, Houston Press Club, Society of Professional Journalists, Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club, Public Citizen Texas, and Associated Press Managing Editors. He is a former staff writer and editor at the San Antonio Current. He is a contributing editor for Texas Climate News and a master’s candidate in International Relations at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas.

Go to Original – gregharman.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.