Six Deceptive Arguments against a Nuclear Weapons Ban

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, 10 Apr 2017

Cesar Jaramillo | OpenCanada – TRANSCEND Media Service

Should we still strive for a world without nuclear weapons, despite global security concerns? Absolutely, writes Cesar Jaramillo, as he debunks the justifications for not taking current negotiations seriously.

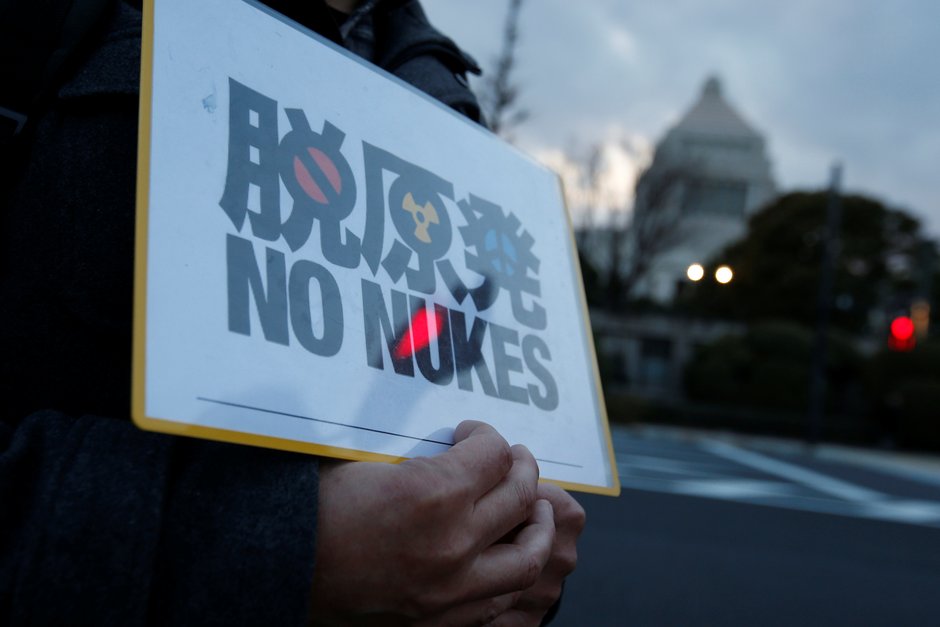

An anti-nuclear protester holds a placard during a rally in front of the parliament building in Tokyo, Japan, March 11, 2017. REUTERS/Toru Hanai

31 Mar 2017 – This year’s multilateral negotiations toward a legally binding prohibition on nuclear weapons reflect a growing global recognition that a nuclear-weapons ban is an integral part of the normative framework necessary to achieve and maintain a world free of nuclear weapons. For some observers of nuclear issues, in and out of government, they also constitute a welcome shock to an otherwise lethargic nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime.

UN Resolution L41, which calls for negotiations toward a new ban on nuclear weapons, was adopted by a wide majority at the General Assembly last December (123 for, 38 against, 16 abstentions). It epitomizes a new political reality in the nuclear disarmament realm: Founded on the humanitarian imperative for nuclear abolition, it bears witness to a widely held perception that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), as currently implemented, does not constitute a credible path to abolition.

Negotiations stemming from L41 began this week at the United Nations in New York and, after the first round ends Friday, will continue June 15 to July 7. All UN member states, along with international organizations and members of civil society, were called on to participate. Yet, several did not.

A majority of nuclear-armed states and their allies — including the United States and most other NATO members, such as Germany and Canada — have actively opposed this effort and have openly tried to undermine its rationale.

The U.S. envoy to the UN, Nikki Haley, attempted to justify her country’s absence this week by telling reporters, “There is nothing I want more for my family than a world with no nuclear weapons. But we have to be realistic… Is there anyone that believes that North Korea would agree to a ban on nuclear weapons?” (As she said this, she confirmed that the U.S. itself did not agree to a nuclear weapons ban. The irony, of course, was not lost.)

And while it is hardly surprising that the very states that rely on nuclear deterrence would oppose a legal prohibition of nuclear weapons, the primary arguments used to oppose the ban cannot withstand close scrutiny. They are either misleading, based on a dead-end logic, or outright wrong.

Let us consider six of the most commonly cited arguments.

- Negotiations fail to consider the global security environment.

This point has been frequently raised by opponents to condemn negotiations before they even start. In reality, however, neither the way in which the talks will unfold nor possible outcomes are predetermined. These naysayers have been repeatedly urged by a majority of NPT and UN states parties to participate in the talks, which would allow them to raise any and all international security concerns they may have. Instead, they preemptively indict the process and choose instead to boycott the negotiations.

Following its vote late last year against the proposal to convene the negotiations, the U.S. issued an explanation, which was echoed by several states including, remarkably, Russia. In it, the U.S. spoke of the purported “negative effects of seeking to ban nuclear weapons without consideration of the overarching international security environment.” Similarly, France has also said, “A prohibition of nuclear weapons, in and of itself, will not improve international security.”

Nobody, however, is advocating for a ban in isolation, and it has never been said that the global security environment would not be considered. Thus, we are led to wonder what else could be meant by “consideration of the overarching international security environment.” Is it that preserving international security requires the preservation of nuclear weapons? Or simply that there are difficult security challenges now facing the international community (which no one disputes)?

There is no perfect time to seek nuclear disarmament — or world peace or the end to hunger or equal pay for equal work. We cannot create a need for ideal conditions that will only become an excuse in perpetuity for the lack of progress. Non-nuclear-weapon states have never made the fulfillment of their nonproliferation obligations contingent upon the emergence of ideal international security conditions — and would surely be chastised by the nuclear-armed states if they did.

Achieving nuclear abolition will be a lengthy undertaking that will necessarily coexist with international security crises of varying gravity. To expect otherwise is unbelievably — and perhaps deliberately — naïve.

- A nuclear-weapons ban would be ineffective.

In some forums, the states opposing ban negotiations openly question the impact and effectiveness of a prohibition treaty; in others, they admit that the process could have profound implications for the perpetuation and legitimacy of practices related to nuclear weapons. Remarkably, one of the best articulations of the significance of a legal ban comes from the U.S. and reflects NATO thinking and policy.

In an unclassified NATO document from October 2016 entitled “United States Non-Paper: ‘Defense Impacts of Potential United Nations General Assembly Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty,’” a legal prohibition of nuclear weapons is presented as anything but insignificant or ineffective. In it, the U.S. openly calls on all allies “to vote against negotiations on a nuclear weapons treaty ban, not to merely abstain.” It further asks allies and partners to refrain from joining the actual negotiations.

The document, which acknowledges that “the effects of a nuclear weapons ban treaty could be wide-ranging” and “could impact non-parties as well as parties,” lists several ways in which the ban could impact NATO’s standing as a nuclear-weapons alliance. For example, a ban treaty could put limits on:

- nuclear-weapons-related planning, training, and transit;

- assisting or inducing allies to use, plan, or train to use nuclear weapons;

- the use of nuclear-capable delivery systems; and

- nuclear-weapons-sharing practices among NATO members

The document succinctly points to the indisputable intersection between the rationale for the ban and NATO resistance to it: “Such treaty elements could—and are designed by ban advocates to—destroy the basis for U.S. nuclear extended deterrence.” Indeed.

- The process to ban nuclear weapons is divisive and not based on consensus.

Opponents contend that negotiations to ban these weapons will create a schism in the international community, especially in the absence of nuclear-weapon states — whose presence continues to be widely encouraged.

Indeed, these talks will be divisive. But they simply shed further light on longstanding divisions, which continue to be exacerbated by the blatant disregard of nuclear-weapon states for their obligations to disarm.

It should be noted that the very countries that blocked consensus in the process surrounding the nuclear-weapons-ban negotiations, including the adoption of Resolution L41, are now criticizing the lack of consensus. Following its vote against the proposed negotiations, NATO member and nuclear-armed France said in its explanation of its vote (endorsed by the UK and the U.S., both possessors of nuclear arms) that “only a consensus-based approach” could lead to progress in nuclear disarmament.

Perplexingly, states wishing to undermine the negotiations continue to point to their own unwillingness to participate as an inherent flaw in the process.

- A legal prohibition of nuclear weapons is no substitute for actual weapons reductions.

True. A legal instrument to ban nuclear weapons, however thorough or stringent its provisions, will not automatically result in fewer nuclear warheads in the hands of any actor. Not a single proponent of the ban argues that this effort will be tantamount to abolition. The ban’s limitations are well known. The need for buy-in from nuclear-weapon states is undisputed. But the lack of specific provisions for disarmament is not an indicator of ineffectiveness.

The historic adoption of Resolution L41 and the process surrounding it constitute the strongest diplomatic signal in decades that the peoples of the world reject these horrifying instruments of mass destruction. Critically, these developments could well signal a turning point in the humanitarian, diplomatic and political struggle toward their elimination.

The global momentum and political will to move the ban forward are unprecedented in the post-Cold War era. The lack of interest signalled by nuclear-weapon states and their allies may indicate that the process is starting to become a diplomatic annoyance for them.

Many recent and current international efforts related to nuclear weapons did not and will not reduce the size of nuclear arsenals. Various UN panels of governmental experts, high-level meetings related to the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty, and NPT-endorsed plans of action, which produced no warhead reductions, have received multilateral support over the years. Why should negotiations on a ban be denied similar backing?

- The pursuit of a nuclear-weapons ban undermines the NPT.

Opponents to nuclear-weapons-ban negotiations frequently declare that this process effectively undermines the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. In fact, the contrary is true. The negotiation of a nuclear-weapons ban constitutes a rare, specific instance of actual implementation of Article VI of the NPT, which calls on states to “pursue negotiations in good faith” toward nuclear disarmament.

The World Court in 1996 further clarified the Article VI obligation. It indicated that the NPT requires states not only to engage in good faith negotiations for nuclear disarmament, but also to bring them to a conclusion.

The NPT was designed to prevent non-nuclear-weapon states from acquiring nuclear weapons and to compel nuclear-weapon states to eliminate their arsenals. In no direct or implied phrase does the treaty limit complementary efforts, such as negotiations toward a nuclear-weapons prohibition, to implement its provisions and advance nuclear disarmament.

Those with nuclear arsenals have resisted, avoided, or ignored not only their treaty obligations, but the groundswell of support for nuclear abolition from all corners of the planet.

- Better than a ban is a so-called progressive, pragmatic approach to nuclear disarmament.

Nuclear-weapon states and their allies continue to insist on a step-by-step approach that, 45 years after the NPT came into force and nearly three decades after the end of the Cold War, has not attained the goal of complete nuclear disarmament. In effect, they are opting for the status quo.

No credible multilateral undertaking now exists that will lead to nuclear disarmament in the foreseeable future. Efforts to further the nuclear disarmament agenda have withered when denied support by nuclear-armed states.

This approach is increasingly out of sync with the emerging, compelling, and persuasive narrative voiced by a majority of the world’s nations, which says that a legal ban is not only urgently needed, but indeed possible.

A deep-seated skepticism about the state of the nuclear disarmament regime, shared by a growing number of multilateral actors, is not just based on doubts about future progress but on historical evidence and current practice. Developments such as the rapid, costly modernization of nuclear arsenals and related infrastructure (some estimates put the price tag at more than $1 trillion), heightened tensions between superpowers, and a dysfunctional multilateral disarmament machinery, underscore the inadequacy of the current approach to nuclear disarmament.

The nuclear-weapons-ban movement must be understood in this context. It developed out of the failure of the NPT to deliver on the promise of complete nuclear disarmament. The “pragmatic” approach advocated by those resisting a legal ban has already been tried — and has been found wanting.

________________________________________

Cesar Jaramillo is the Executive Director of Project Ploughshares.

Cesar Jaramillo is the Executive Director of Project Ploughshares.

OpenCanada is a digital publication sitting at the intersection of public policy, scholarship and journalism. We produce multimedia content to explain, analyze and tell stories about the increasingly complex and rapidly shifting world of foreign policy and international affairs.

Go to Original – opencanada.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: