Manus a Humanitarian Crisis: How Did We Get to This Point in Papua New Guinea, Australia?

ACTIVISM, 13 Nov 2017

Holly Brooke & Vanamali Hermans – New Matilda

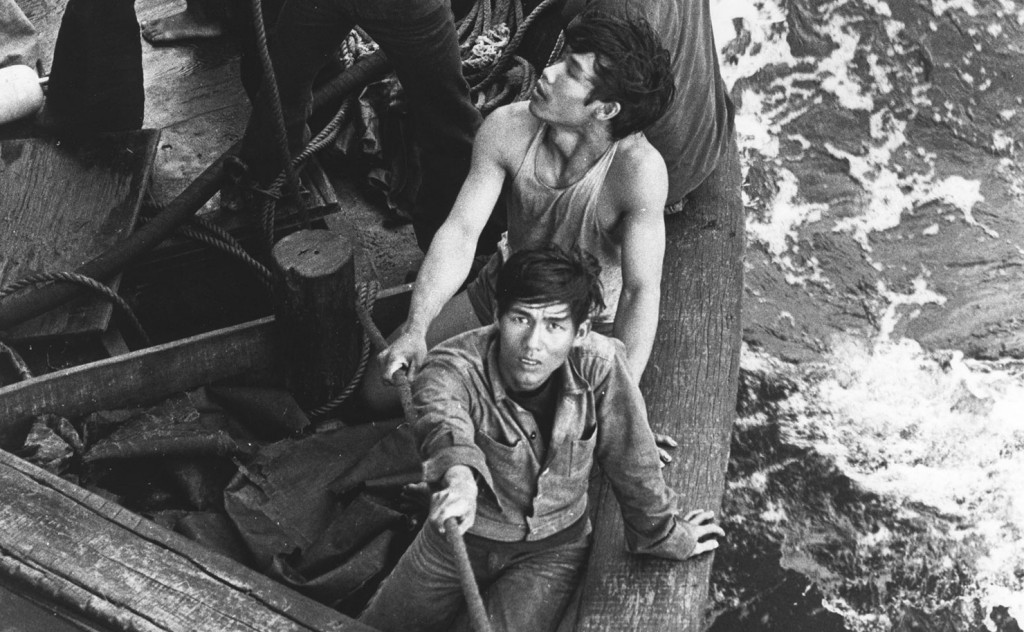

A file image of Manus Island detainees, who protested every day at 2pm, against their relocation from the processing centre set at a naval base, to the nearby transit centre. The move came in the wake of a PNG High Court decision which found the processing centre illegal.

3 Nov 2017 – As of 10:00am today students are leading simultaneous occupations of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection offices in Canberra and Sydney. The protesters plan to remain inside the offices until they receive a statement from Immigration Minister Peter Dutton confirming a plan to ensure the safe evacuation of the 600 refugees currently facing humanitarian crisis on Manus Island to Australia. Two of the protestors, Holly Brooke and Vanamali Hermans, explain their actions.

Today, along with other students, we are occupying the Canberra and Sydney Departments of Immigration, demanding the immediate evacuation of Manus Island refugees to Australia. We are here because successive governments have failed to take action on refugee policy and because we cannot sit idly by watching horror and abuse unfold.

Since Tuesday, all final services and security have been stripped from the Manus Island Detention Centre as part of its long awaited ‘shut down’ since the Supreme Court of PNG’s ruling of illegality in April last year. This shut down has left those in the centre without food, water or power, and in grave fear for their safety. Soon after security left the centre, locals – angry about the lack of consultation regarding relocation of refugees into the community – entered and looted some parts of the compound. Looming over the asylum seekers on Manus is the threat of a take-over by PNG paramilitary groups infamous for violence, murder and human rights abuses.

Refugee Behrouz Boochani, currently on Manus Island, stated to the ABC, “The police already, they beat some of the refugees and the local people. They attacked the refugees and rob them. This place is not a safe place.”

And so, to many Australians, the question that springs to the fore when reading of the horrors being carried out on Manus Island in our name is: how did we get to this point?

The humanitarian crisis we see unfolding on Manus Island has not arisen from nowhere, and was not unforeseen. It is an inevitable result of an evolving social calculus, designed to break vulnerable people seeking safety, and convince a nation that this cruelty is necessary.

During the post-war period, Australia took part in drafting the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, was among the first states to accede to the Convention in 1954, and between 1947 and 1954, accepted roughly 170,000 people displaced from Eastern Europe. There was a bipartisan view that ‘Australia had international obligations to protect refugees, regardless of how they arrived in Australia’.

This view began to shift in the 1960s and 1970s, when refugees began arriving by boat from Asian countries. The unannounced arrival of non-white asylum seekers stirred xenophobic sentiment, and when, in the early 1980s, annual humanitarian arrivals twice surpassed 20,000, criticism became audible. With the arrival of the ‘second wave’ of refugee boats after 1989, this time from Cambodia, the Hawke government announced that arrivals from Cambodia would not automatically be classed as refugees. It was at this time that the language surrounding asylum seekers arriving by boat began to refer to the notion of ‘queue-jumping’ to bypass the Australian government’s ‘orderly migration program.’

In 2001, throughout the ‘Tampa affair’ and ‘Children Overboard’ incident, this language again evolved to take on an even more sinister tone. The spectre of 9/11 hung in the air, rustling up ever-more racist sentiment in the Australian public; sentiment the Howard Government capitalised on. Asylum seekers were framed not only as queue-jumpers, but as terrorists and as inhumane criminals who would risk the safety of their children.

In both the Tampa and Children Overboard incidents, there was specific Government direction to suppress any and all media that could humanise asylum seekers in the eyes of the Australian public [2]. The stories in circulation were instead those crafted by the Australian Government in a deliberate attempt to harden public sentiment against asylum seekers. This served to justify ever-harsher measures taken by the Australian government to ‘protect Australia’s borders’ and ‘prioritise national security’ without fear of repercussion from the electorate.

Once this hard-line anti-refugee stance had been established there could be no backing down lest the Government risk looking weak and losing popularity. It has since been politically necessary for successive Governments to ensure that the Australian public remains unsympathetic towards asylum seekers, so that the stance they continue to take regarding border policy remains popular.

The events of 2001 illustrate one phase of the vicious cycle of abuse perpetrated by successive Australian Governments with regard to asylum seekers. The Howard Government’s ‘Pacific Solution’ of 2001 to 2007, the Gillard Government’s return to offshore processing in 2012, the Rudd Government’s 2013 ‘PNG Solution’, and the Abbott Government’s highly successful 2013 ‘Stop The Boats’ election platform all illustrate a ‘race to the bottom’, so to speak, whereby ever-more callous denials of asylum seeker rights have been used as a domestic political platform.

This race to the bottom has culminated this week in the humanitarian crisis currently unfolding on Manus. And still, even in the face of this horror, the Australian Government is not acting to evacuate the people on Manus Island to safety in Australia, and large chunks of the Australian public remain unsympathetic. This humanitarian crisis could be ended at any time by a single phone call from Peter Dutton or Malcolm Turnbull. However, a move on the part of the Government to end this crisis would recognise that the assumed racism of the Australian public is not as strong as is the media and Government policy would suggest, and thus undermine the the political benefits to the Government in maintaining racism in the electorate.

Widespread anti-refugee sentiment in the Australian public is useful and necessary to maintaining the status quo for the Australian top 1% and political class. When successive governments pursue agendas of privatisation and cuts, big businesses – which conveniently line the pockets of both major parties – profit, while everyday people suffer. The ‘dole bludging’, ‘job-stealing’ foreigner is a carefully cultivated scapegoat upon whom governments deflect blame when working people in Australia feel the pinch caused by ever-increasing inequality. The horrific human rights abuses inflicted upon thousands of people by the Australian Government are simply collateral damage for political gain.

We as Australians can now choose to continue to remain beholden to the propaganda spread by our Government, and to stand by while these abuses are perpetrated in our name, or we can choose to stand up and speak out. An end to this crisis will not be brought about by those in power simply deciding one day to respect the human rights of asylum seekers and refugees. Historical struggles have shown us that human rights are not bestowed, but are hard fought for and won through mass mobilisations that give those in power no option but to accede.

We all like to think that if we had lived through times of grave human rights abuses – the holocaust, or apartheid – we would have said something; we would have been a part of the movements that fought for human rights. A humanitarian crisis is happening under our watch, in our name, and now is the time to do something, and to be part of a movement that fights for human rights.

There are several things you can do to take a stand against this injustice. Ringing politicians’ offices and putting political pressure on both major parties is important in communicating that the treatment of asylum seekers does not have social licence, and that the Australian public is aware of our politicians’ complicity in their harm.

Just as important is mobilising this pressure. Over the weekend refugee action groups across the country are holding protests demanding the safe evacuation of asylum seekers on Manus Island to Australia. Junkee has compiled a list of all the rallies occurring across major cities, which are critical in showing the government that the majority of the Australian electorate stands for the fair and humane treatment of refugees.

If you live in regional Australia, or can’t get out to a rally, talking about the issue is just as valuable. Whether it be with family, friends, or co-workers, the only way we start to bust some of the myths about asylum seekers is by engaging in genuine conversations with the people we know. Getting the office to take a solidarity picture with hashtags like #BringThemHere, sharing articles on social media or getting on the phone with grandma are all important steps in starting to shift our discourse around refugees. During the marriage equality campaign and postal survey we have seen how effective these actions can be in changing people’s mind and hearts – we know it can work in this situation too.

Finally, if like us, you want to take direct action and organise to bring about an end to this crisis and policies like offshore processing and mandatory, indefinite detention, you can join your local Refugee Action Coalition or similar refugee campaigning community group. RAC’s exist in every state and drive refugee campaigns across the country. They enable anyone, whether you have a history of activism or not, to stand in solidarity with refugees and engage with actions like the one we are taking today.

___________________________________________

Holly Brooke and Vanamali Hermans are both university students, and involved in protests on November 3 at simultaneous occupations of the Sydney and Canberra offices of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Go to Original – newmatilda.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.