U.S.A. Participation in World War One

HISTORY, ANGLO AMERICA, MILITARISM, EUROPE, 12 Nov 2018

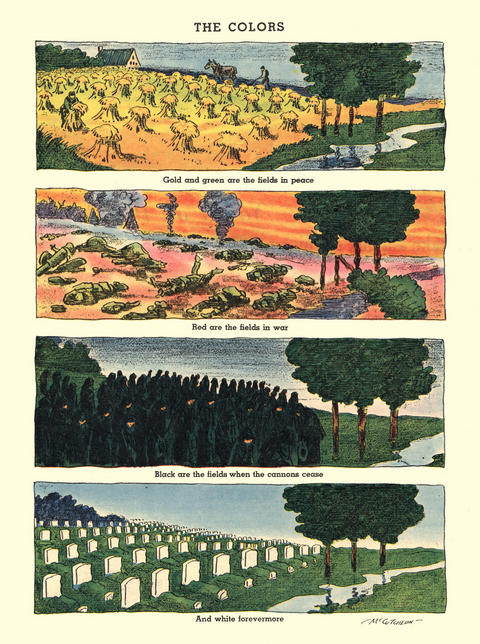

John T. McCutcheon, Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1914.

“Gold and green are the fields in peace. Red are the fields in war. Black are the fields when the cannons cease. And white forever more.”

Did you know?

- For the first 32 months of the Great War, known as World War I today, the U.S. remained officially neutral. President Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election in 1916 on a campaign slogan, “He Kept Us Out of War.”

- In his war message to Congress on April 2, 1917, President Wilson declared that the “present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” Senator George Norris of Nebraska suggested that U.S. ships not sail into war zones as an alternative to war.1

- President Wilson framed the war as a fight for “the rights of mankind,” but instituted policies at home that curtailed American Constitutional rights, including freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

- The idea of the Great War as “the war to end all wars” originated with British fiction writer H. G. Wells in August 1914.

- Upon entering the war, the U.S. government initiated a chemical weapons program that involved more than 1,900 scientists and technicians, making it the largest government research program in American history up to that time.2

- More than two million U.S. soldiers were sent to France. Most arrived in the late spring and summer of 1918 and fought for less than six months.

- American fatalities included 53,402 soldiers killed in combat or missing, and 63,114 deaths from disease. Of the latter, roughly 45,000 U.S. soldiers died from the influenza epidemic that swept the U.S. and Europe in 1918.3

- All in all, the Great War took the lives of almost ten million soldiers. U.S. military deaths (116,516) constituted just over one percent.4

- Contrary to the heroic image of warfighting in all countries, two-thirds of all deaths and injuries in battle resulted from artillery and mortar fire from afar. Another 90,000 soldiers died from poison gases.5

- At least ten million civilians died as a result of the Great War. Food shortages in Germany, due to the British blockade, are estimated to have caused 763,000 deaths, according to the National Health Office in Berlin. This was about 50 times the number of British deaths caused by German submarine attacks on merchant vessels.6

- The fighting ended on November 11, 1918, at 11:00 a.m. That date is commemorated today in the United States as Veterans Day, a national holiday.

- According to a Gallup poll in 1937, 70% of Americans believed that U.S. participation in the Great War was “a mistake.”7

I. Introduction: The great reversal

When the Great War erupted in Europe in August 1914, few Americans believed that the United States should become involved. There was a long tradition of avoiding “entangling alliances” with European powers, dating back to George Washington, and the United States itself was not threatened. The main concern expressed by some Americans was that the war could disrupt U.S. trade and cause an economic downturn. President Woodrow Wilson, speaking on August 3, advised Americans to remain calm. He expressed confidence that the U.S. would be able to “meet the financial situation growing out of the European war.”8 Two weeks later, he appealed to Americans to avoid taking sides:

The United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name during these days that are to try men’s souls. We must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another. The United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name.”9

The major antagonists in the Great War were the Central Powers of Austria-Hungary, Germany and the Ottoman Empire, and the Triple Entente or Allied Powers of Russia, France, and Great Britain, later joined by Italy. The immediate cause was an attempt by Austria-Hungary to take over Serbia, a small country on its southern border, following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. The larger issue was which of the great powers would have dominant influence in Europe and the Middle East.

During the first 32 months of the 51-month war, the U.S. remained officially neutral. Yet the U.S. was not neutral in practice. The Wilson administration forged ever closer ties with Great Britain, supplying the Allied nations with food, guns, ammunition, and huge loans to pay for it all. Much of that loan money was spent in the U.S., creating an economic boom and also linking American prosperity to an Allied victory.

At the outset of the war, the British set up a naval blockade of Germany, mining harbors and cutting off U.S. trade. The Wilson administration feebly protested this denial of “neutral trade rights” but let it go on. In February 1915, Germany responded with a blockade of its own, a submarine cordon around the British Isles. Although Germany’s intent was to sink enemy merchant ships, not neutral ships, the Wilson administration demanded that Germany abandon the policy.

Over the next two years, more than 98 percent of ships sent to the bottom by German U-boats (submarines) were British or French. To deceive their attackers, British merchant vessels sometimes hoisted American flags, thus encouraging mistakes.10 German U-boats and raiders sank or damaged a total of eight U.S.-registered vessels prior to February 1, 1917, with total American casualties amounting to three dead and one wounded. In the one case where fatalities occurred, the attack on the steamship Gulflight on May 1, 1915, the German government apologized.11

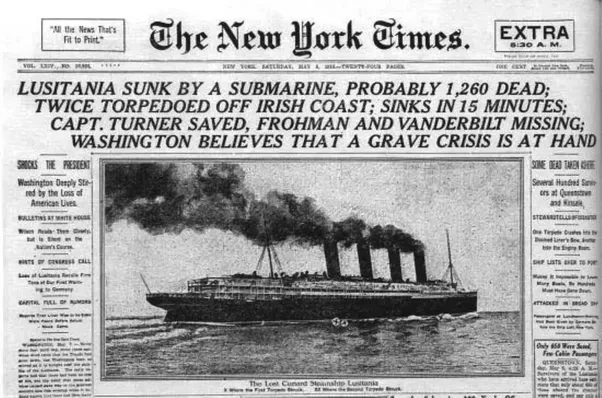

The main issue of contention between the U.S. and Germany during the U.S. neutrality period was not the sinking of a few U.S. merchant ships, but the Wilson administration’s insistence that American citizens had the right of safe passage on belligerent ships in war zones, a transparent attempt to protect British and French vessels by placing Americans on board. The issue became acute when a German U-boat torpedoed the British luxury liner Lusitania, on May 7, 1915, resulting in the deaths of 1,198 crew members and passengers, including 128 Americans. Unbeknown to passengers aboard, the Lusitania was carrying a large cache of ammunition in its hull.12

Winston Churchill, first Lord of the Admiralty, hoped that the Lusitania crisis would push the U.S. into war on the side of the Allies, writing to another government official, “It is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany. . . . For our part we want the traffic — the more the better; and if some of it gets into trouble, better still.”13

The German government, for its part, attempted to appease the U.S. by restricting its submarine warfare. It issued the Arabic Pledge on September 1, 1915, promising advanced warning before sinking an enemy merchant or passenger ship, and the Sussex Pledge on May 4, 1916, promising to ensure the safety of passengers and crew if a ship was sunk. The latter pledge contained an important caveat: Berlin reserved the right to abandon these restrictions if the United States did not compel Great Britain to end its blockade in conformity with international law.14 The Wilson administration did not do this. Indeed, the British expanded their blockade to include neighboring neutral countries, preventing even food from reaching Germany and creating conditions of starvation.15

This was the context in which the German government decided to initiate unrestricted submarine warfare in the waters surrounding the British Isles, beginning on February 1, 1917. German leaders sought to deprive Great Britain of outside support by sinking all merchant ships in these waters, including those flying the American flag. Between February 1 and April 6, the day the U.S. declared war on Germany, German U-boats sank ten U.S.-registered ships, resulting in the deaths of 64 crewmen, 24 of them American.16

On April 2, 1917, President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, asserting that the “present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.”17 Wilson presented the situation as if there was no other option. Yet there was a practical alternative: require that U.S. cargoes be delivered by British merchant vessels instead of American vessels. Senator George Norris of Nebraska, who voted against the war resolution, made this point on the Senate floor on April 4, saying, “We might have refused to permit the sailing of any ship from any American port to either of these military zones.”18

The fact that the United States itself was not in any danger of attack meant that the most reliable justification for war, national self-defense, was lacking. The president thus chose to frame German attacks on U.S. merchant ships as an attack on America’s “honor” and, more broadly, as “warfare against mankind.” He further embellished his justifications for war by stating that the U.S. would fight for “the rights of all mankind” and that “the world must be made safe for democracy.” That the U.S. had no pressing national self-interest at stake was spun into a virtue by declaring that the U.S. had “no selfish ends to serve.”19

Wilson also justified going to war by promising a more peaceful world order in its aftermath via a new League of Nations; hence the idea of “a war to end all wars.” The League proposal did not originate with Wilson. It had been circulating for more than a decade, gaining support among both conservatives and liberals in the United States and Great Britain. Former president Theodore Roosevelt endorsed a “League of Peace” in 1910, and former president William Howard Taft became its leading advocate before Wilson adopted the idea in May 1916.20 The British government developed a draft proposal in early 1918 and Prime Minister David Lloyd George arrived at the Paris peace negotiations with a proposal in hand.21 The United States did not need to go to war to create the League of Nations. Rather, President Wilson needed the promise of a new world order to justify going to war.

First Lady Edith Wilson, with the president, lays a wreath at the American Military Cemetery at Suresnes, France, May 31, 1919

The U.S. sent over two million soldiers to France, although most did not arrive until the summer of 1918. The American Expeditionary Forces played an important role in the last battles of the war, buoying up British and French forces. The cost was 53,402 U.S. soldiers killed in combat or missing, and 204,002 wounded. Another 63,114 soldiers died from disease, half in military camps in the United States. The total number of U.S. military deaths (116,516) nevertheless constituted less than two percent of all Allied fatalities and slightly more than one percent of all combatant deaths.22

At the Paris peace conference, Wilson’s idealistic pronouncements had little bearing on the negotiations. America’s allies carved up the Ottoman Empire as spoils of war and imposed heavy reparation payments on Germany, sowing resentment that laid the groundwork for another world war. Wilson had initially suggested a less punitive treaty, but he was not displeased with the final outcome. Speaking to reporters after the conference, he described the Treaty of Versailles as “a wonderful success” and declared, “I am proud of it.”23

Was it necessary, in the final analysis, for the U.S. to enter the Great War?

Had the U.S. maintained strict neutrality, not only would American lives have been saved, but the U.S. could have acted as a legitimate mediator of the conflict, working with other neutral nations to pressure the belligerents to end their slaughter short of annihilation and starvation. The war might well have ended sooner and on more balanced terms, thus removing one cause of the rise of Nazism and the Second World War.24 Certainly, U.S. neutrality would have prevented one regrettable chapter in U.S. history: the suppression of First Amendment rights and freedoms. Wilson’s imagined crusade to make the world “safe for democracy” was accompanied by repressive laws that made democracy unsafe in America.

This essay synthesizes the work of many historians of the First World War. The next section provides an overview of the European war, including its complex origins and the efforts of peace advocates to prevent it. Sections III and IV discuss the origins of U.S. intervention in the war between 1914 and 1917, examining the Wilson administration’s moves toward war, underlying economic interests, and overarching ideological rationales. Sections V and VI discuss American experiences in the war, especially from the soldier’s vantage point, and the lamentable peace settlement in Paris. Section VII, “The Nadir of American democracy,” charts the U.S. government’s repression and state propaganda along with vigilantism and intolerance on the home front during the war years. Section VIII surveys the efforts of peace advocates to keep the U.S. on a course of neutrality, identifying four phases of the peace movement.

II. The Great War in Europe and beyond

Had European leaders known what was to come when they declared war on each other in the summer of 1914, they might have paused to consider peaceful, diplomatic options. No one expected a long war at the outset. Indeed, German leaders predicted victory in 42 days. There had been six wars among the various belligerents in the previous forty years and all had been short: the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Russo-Turkish War of 1878, Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, and two Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913.25

The Great War went on for over four years and three months, partly because the two belligerent alliance systems were roughly equal in power (though not population and resources), partly because defensive weaponry and tactics trumped all offensive maneuvers on land until almost the end, and partly because the leaders of both sides were too proud and ambitious to negotiate a peace settlement despite massive casualties and suffering.

Gavrilo Princip fires at Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in illustration in Italian newspaper, July 1914

The Great War, at root, was the product of empire-building. Three great states were vying for control of the Balkans: the Ottoman Empire, which formerly held the region, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. At the same time, small states such as Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece were seeking to expand their borders. The immediate catalyst to war was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, on June 28, 1914. The fatal bullets were fired by 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, in the city of Sarajevo.26 The plot was hatched with the support of Dragutin Dimitrijević, Chief of Serbian Military Intelligence, who led a secret group known as the Black Hand that was dedicated to liberating all Slavic peoples from Austro-Hungarian rule.

Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary used the occasion to demand that Serbia suppress all popular agitation against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Although the Serbian government largely agreed to Emperor Joseph’s provocative demands, with the exception of a provision to allow Austrian investigators to investigate the archduke’s assassination, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, its motive being to incorporate Serbia.27

It took one month for the war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia to germinate but only one week for the conflict to metastasize into a world war involving the great powers of Russia, Germany, France, and Great Britain. Czarist Russia, unwilling to allow Austria-Hungary to gain more territory in the Balkans, came to Serbia’s defense and began mobilizing its military forces. Imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary’s ally, viewed Russian mobilization as a grave and immediate danger to the German homeland and declared war on Russia on August 1. Two days later, Germany declared war on France, Russia’s ally, and began preparations to invade France through Belgium.

As the world crisis unfolded, all eyes turned to Great Britain. Would the most powerful empire in the world enter the war? On Sunday, August 2, a large antiwar demonstration was held in Trafalgar Square, London. James Keir Hardie, a Scottish Labor Party leader, called for a general strike if Britain declared war. “You have no quarrel with Germany!” he told the crowd.28 The following day, Foreign Affairs Secretary Sir Edward Grey addressed the House of Commons and solemnly declared that his government could not remain neutral due to an 1839 treaty commitment to defend Belgium and an unspecified “commitment to France,” owing to the Anglo-French entente of 1904.29

Grey nonetheless assured legislators that he would consult them in the event of a crisis. This he did not do. After receiving reports of German troops marching through Belgium, the British government of Herbert H. Asquith declared war on Germany on August 4, without a Parliamentary vote. Prime Minister Asquith stated that the British would fight “not for aggression or the advancement of its own interests, but for principles whose maintenance is vital to the civilized world.” That same day, Le Matin, a major French newspaper, called the conflict a “holy war of civilization against barbarity.”30

Italy, the weakest of the great powers in Europe, had been part of a Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary since 1882, but Italian leaders insisted that the alliance was solely for defensive purposes and thus they refused to support Austria-Hungary’s gamble for Serbian territory. Italy remained neutral for ten months, then joined the Allied Powers after secretly being promised slices of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after victory. The Ottoman Empire, meanwhile, formally joined the Central Powers in late October 1914, being a traditional rival of Russia. Europe was not entirely divided by war, as Spain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden remained neutral throughout.

The global war

Germany planned to first conquer France then join Austria-Hungary in defeating Russia whose vast expanse of land and large population made it a daunting foe. The German invasion of Belgium and northeastern France proceeded quickly and brutally in August 1914. The German Army drove within 30 miles of Paris before stopping to allow its supply lines to catch up. French and British forces counterattacked in the Battle of the Marne, September 6-12, leading to a partial retreat by German forces.

The Western Front then settled into a murderous stalemate for the next three and a half years. Both sides dug trenches in northern France that stretched from the English Channel to the Swiss border. The area between the trenches, dubbed “no man’s land,” became a graveyard for millions of men. Infantry soldiers charged headlong into barbed wire, machine guns, artillery barrages, and poison gas. Defensive strategies trumped all offensive maneuvers and the Western Front never moved more than a few miles in either direction. The major battles at Verdun and the Somme River produced immense casualties. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916, British casualties numbered 57,000, including 19,240 killed, making it the bloodiest day in British military history. The battle lasted five months and resulted in a total of 1.2 million casualties on all sides.31

The belligerent armies were more mobile on the Eastern Front. Instead of trench warfare, there were sweeping movements, breakthroughs, and retreats. In the first year of the war, the Russian Army invaded eastern Germany (now Poland), ruthlessly burning villages as it advanced. It then suffered a series of crushing defeats, being short of ammunition, artillery, and food, and retreated. Austro-Hungarian forces, meanwhile, invaded Serbia but suffered heavy losses and withdrew. Russia temporarily regained the initiative from June to October 1916, breaking through Austro-Hungarian lines and forcing Germany to redirect some of its troops to the Eastern Front.32

Success in battle, however, did not ameliorate deprivation on the Russian home front. Food riots and demonstrations rocked Russian cities in February and March 1917, and whole military units refused orders to deploy to the front. Recognizing the dire situation, Russian Army commanders asked Czar Nicholas to resign. He did so on March 15, leaving the shaky government in the hands of Alexander Kerensky, a moderate socialist. Kerensky continued the unpopular war, authorizing a new offensive in July 1917. When the Germans counterattacked, the Russian Army fell apart. In some units, soldiers shot their own officers and started walking home. By August, Russia had given up all the territory it had regained in 1916.

The Kerensky government’s determination to continue the war proved its undoing. The Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, promised “Peace, Bread, and Land.” In late October 1917, the Bolsheviks overthrew the Kerensky government. The new government concluded an armistice with Germany on December 15, followed by a peace treaty on March 3, 1918. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk formally ended Russian participation in the war and ceded huge swaths of territory to Germany. The Allies were displeased with both Russia’s withdrawal and the new Bolshevik government. Great Britain, France, and the U.S. subsequently dispatched troops to aid the overthrow of the new government – contrary to President Wilson’s promise to respect Russian self-determination.33

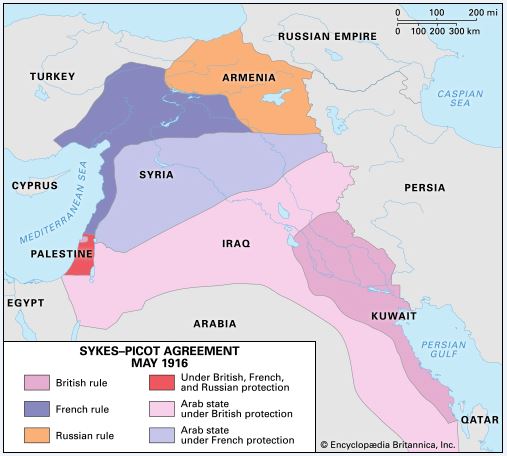

The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France set forth how the Ottoman Empire would be divided as spoils of war

The Great War extended beyond Europe. In the Middle East, the British moved quickly into Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) to establish control over oil fields against Ottoman resistance. Led by T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), the British also organized an Arab rebellion within the Ottoman Empire, promising independence after the war. This turned out to be a false promise. Following the war, the British took control of what is today modern Iraq, Israel and Jordan, and France reigned over Lebanon and Syria.

In Africa, the British attacked the German colonies of Togo, Cameroon, and German East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania without Zanzibar today), while British-allied South Africa seized the German protectorate of South West Africa (Namibia) in 1915. In Asia, Japan declared war on Germany on August 23, 1914. With cooperation from the British Navy, Japanese troops took over the German-occupied port of Qingdao on China’s Shandong Peninsula. China waited until August 1917 to declare war against Germany, mainly to earn a place at the post-war bargaining table and regain control of the Shandong Peninsula.

The British and French drew upon their far-flung colonial empires for support and soldiers. Former and current colonies – later anointed the British Commonwealth – included about one-fourth of the world’s population in 1914, some 450 million people. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand immediately joined the war effort. Australia and New Zealand together contributed 440,000 soldiers out of a combined population of six million. Of these “Anzac” soldiers, 95,000 were killed, including 8,000 in the Battle of Gallipoli. Their sacrifice continues to be commemorated annually on “Anzac Day,” April 25. Almost 1.5 million Indians served in the Indian Expeditionary Forces as soldiers and laborers, being deployed in northern France, East Africa, and the Middle East.34

The United States entered the war on the side of the Allies in April 1917, but it took more than a year for significant numbers of troops to be trained and transported to France. Germany, meanwhile, was able to move tens of thousands of troops from the Eastern Front to the Western Front after Russia withdrew from the war. Despite starvation on the home front, or perhaps because of it, Germany launched an all-out offensive on March 21, 1918, this time breaking through Allied lines. The German Army reached within forty miles of Paris before having to stop to allow its supply lines to catch up (again). The Allies, with the aid of the American Expeditionary Forces, counterattacked and by September, the German Army was in retreat. An armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, a date commemorated in the United States as Veterans Day.35

Casualties

The total number of military and civilian casualties in the Great War is estimated at 40 million, about half being fatalities. Of the fatalities, 9.7 million were military personnel. The Allied (Entente) Powers lost about 5.7 million soldiers while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. Far from engaging in heroic combat, some two-thirds of the soldiers killed in battle were slaughtered by artillery and mortar fire from afar.36 The wounded included those traumatized by “shell shock” from massive artillery bombardments. Poison gas killed some 90,000 soldiers, including 56,000 Russians, and wounded more than 1.1 million.

The Germans were the first to use poison (chlorine) gas in April 1915, although tear gas had previously been used by both sides. After deploring this “cowardly form of warfare,” the British adopted it, first using poison gas in September 1915. By the end of the war, more than 124,000 tons of poison gases (chlorine, phosgene, and mustard) had been produced by all parties, with the United States taking a leading role in their production in 1917-18.37

Among civilians, famine and disease were the bigger killers. The German National Health Office reported in December 1918 that 763,000 civilians had died due to food shortages caused by the British blockade, which resulted in malnutrition and susceptibility to disease. After four years of the blockade, women’s mortality rate was up 51 percent and that of children under five, 50 percent. Another 100,000 Germans perished between the armistice on November 11, 1918, and the signing of the peace treaty on June 28, 1919, as the British maintained their blockade to keep pressure on German leaders to sign the peace treaty. Famine also stalked Russia and the Balkan states.38

Invading armies were prone to kill and abuse civilians when suppressing resistance. According to the historian Alan Kramer, the German Army intentionally executed 5,521 civilians in Belgium and 906 in France during its initial invasion. The victims included women and children, and especially men of military age. One German soldier who had participated in a massacre in the town of Dinant, Belgium, told his French captors, “We were given the order to kill all civilians shooting at us, but in reality the men of my regiment and I myself fired at all civilians we found in the houses from which we suspected there had been shots fired; in that way we killed women and even children.”

The Russian Army, too, notes Kramer, “committed many acts of violence during its invasion of East Prussia in August/September 1914. Germany denounced the Russians for having devastated 39 towns and 1,900 villages and killed almost 1,500 civilians.”39 German artillery bombarded towns in northern France, including Paris, and both Germany and Great Britain employed aircraft to bomb each other’s cities – a new terror of war.40

One atrocity that stands out was the Ottoman Empire’s systematic assault on its Armenian minority. In response to Armenian agents aiding Allied forces in the Caucasus and Palestine, Ottoman authorities deemed the whole population a threat (there had been previous mass assaults on the Christian Armenians). Beginning in April 1915, the Ottoman military systematically killed thousands of Armenian men in cities such as Bitlis and Trebizond. Hundreds of thousands of women and children were marched south toward Syria without adequate food and water. An estimated 400,000 died from starvation, disease, and murder. Twenty-eight countries, including the United States, have since recognized these actions as “genocide.”41

Total military and civilian deaths, country by country, in descending order, are estimated as follows: Russia, 3,311,000; Ottoman Empire 2,922,000; Germany 2,477,000; France 1,698,000; Austria-Hungary 1,567,000; Italy 1,240,000; Great Britain 995,000; Serbia 725,000; Romania 680,000; Bulgaria, 187,000; Greece 176,000; Belgium 121,000; United States 117,000; Portugal 89,000, India 74,000; Canada 67,000; Australia 62,000; New Zealand 18,000; South Africa 9,500; Newfoundland 1,200; and Japan 415. To these numbers may be added roughly four million people who died in conflicts attributable to the Great War between 1918 and 1923, including the civil wars in Russia, Hungary, and the collapsing Ottoman Empire.42

The memory of the Great War in the United States tends to highlight President Wilson’s noble ideals and his inability to achieve them. In Europe and much of the rest of the world, it is the deadly horror of the war itself that is somberly recalled. “The magnitude of the slaughter in the war’s entire span was beyond anything in European experience,” writes Adam Hochschild:

. . . more than 35 percent of all German men who were between the ages of 19 and 32 when the fighting broke out, for example, were killed in the next four and a half years, and many of the remainder grievously wounded. For France, the toll was proportionately even higher: one half of all Frenchmen aged 20 to 32 at the war’s outbreak were dead when it was over. . . . Roughly 12 percent of all British soldiers who took part in the war were killed. . . . Even the victors were losers: Britain and France together suffered more than two million dead and ended the war deep in debt . . . The four-and-a-half year tsunami of destruction permanently darkened our worldview.43

Winston Churchill, appointed Minister of Munitions in 1917, mused that the war had left “a crippled, broken world.” Lord Lansdowne (Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice), the former British foreign secretary, came to the realization in November 1917 that there was no goal or purpose that could justify continued slaughter. Writing to the Daily Telegraph on November 29, he cautioned British citizens that the war’s “prolongation will spell ruin for the civilized world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weights upon it.” He predicted, “Just as this war has been more dreadful than any war in history, so we may be sure, would the next war be even more dreadful than this. The prostitution of science for purposes of pure destruction is not likely to stop short.”44

The war system and war guilt

Lord Lansdowne was right about the future. Sophisticated weaponry in the next world war obliterated whole cities, first by fire-bombing from the air, then by single nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the span of one lifetime, the character of warfare changed from cavalry charges on horseback to nuclear weapons delivered by aircraft. Of what benefit is science if its products destroy us?

British philosopher and Nobel Laureate Bertrand Russell likewise took note of the misdirection of science, writing in 1916, “Never before have so large a proportion of the population been engaged in fighting, and never before has the fighting been so murderous. All that science and organization have done to increase the efficiency of labour has been utilized to set free more men for the destructive work of the battlefield. . . . The degradation of science from its high function in ameliorating the lot of man is one of the most painful aspects of the war.” Russell also noted how fear and insecurity undermine peace, writing, “Militarists everywhere based their appeal upon fear: powerful neighbours, they say, are ready to attack us, and unless we are prepared we shall be overwhelmed.”45

In the aftermath of the Great War, the victorious Allies were mainly concerned with dismantling German military power rather than reducing militarism per se. Allied leaders at the Paris Peace conference in 1919 pinned the sole blame for the outbreak of war on Germany. Article 231 of the Versailles Treaty, the “war guilt” clause, spelled it out: Germany was responsible “for causing all the loss and damage” suffered by the Allied nations “as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.” This admission of guilt, which the German government was forced to acknowledge, provided the legal basis for reparation payments from the vanquished to the victors. To be sure, Germany was not innocent of the charge of aggression, having initiated the attack on Belgium, but the exclusive focus on its role in causing the war allowed the victorious powers to avoid investigation into the deeper causes of war of which they were an integral part.46

What were these deeper causes? The following factors provide a glimpse of the interconnected war system:

International power politics

- imperial quests for territories, spheres of influence, and economic advantage;

- arms buildups, naval races, and the quest for military superiority;

- the use of diplomacy to gain advantage rather than settle differences;

- the absence, lack of enforcement, or abuse of international laws and norms against aggression;

Domestic institutions and policies

- the use of war to foster militant nationalism and divert social reforms;

- authoritarian decision-making systems and the repression of dissent;

- military-industrial complexes that profit from arm sales and war;

- forced conscription of citizens to fight in wars;

Beliefs and propaganda

- state propaganda that blurs the line between aggression and defense, that dehumanizes the “enemy,” and that indoctrinates citizens with myths of national righteousness;

- racist and pseudo-scientific beliefs that foster notions of racial and national superiority and assume the right to rule over others;

- cultural ideas about manhood, heroism, and war that lead men and boys to want to fight in order to prove themselves;

- military indoctrination that numbs the conscience of soldiers, giving rise to atrocities.

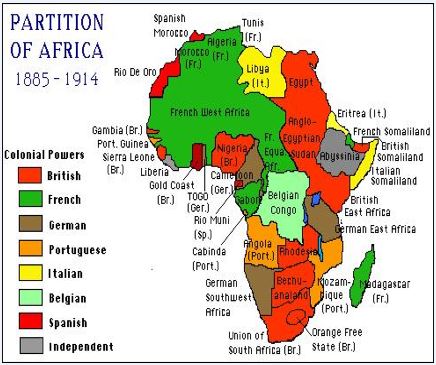

The imperial nations of Europe carved up Africa into colonies, with the democratic nations of Britain and France claiming the lion’s share.

Imperial quests and great power rivalries

Viewing the war from a broad perspective, it may be seen that Austria-Hungary’s aggressive attempt to incorporate Serbia into its empire, which officially catalyzed the Great War, was not different in kind from actions taken by Great Britain to bring East Africa into its realm, or by France to establish its authority over Southeast Asia. The difference was that Serbia is located in southern Europe, an area of vital interest to both Russia and Austria-Hungary, whereas Africa and Asia were deemed peripheral interests. In all cases, nonetheless, imperial force was employed. The historian Jay Winter comments that “the violence Europeans normally practiced on African and Asian” peoples for centuries “came home to roost” in 1914. “What was tolerable when it was Africans, black men or yellow men, becomes intolerable when it has to do with white Europeans. The imperial system allowed for absolutely appalling behavior in the periphery.”47

Allied leaders condemned German militarism and atrocities, and rightly so, yet Great Britain maintained the largest navy and the most expansive colonial empire; and British authorities were not hesitant to use force to maintain and expand their empire. In the Boer War of 1899-1902, in which the British fought Dutch Boers for control of mineral-rich regions in South Africa, British authorities instituted a “scorched earth” campaign aimed at destroying Boer farming communities and food stocks. Destitute Boers arrived at hastily-built internment camps surrounded by barbed wire where they died in droves from famine and disease. “When a final tally was made after the war,” writes Adam Hochschild, “it would show that 27,927 Boers – almost all of them women and children – had died in the camps, more than twice the number of Boer soldiers killed in combat.”48 British ruthlessness in South Africa may be compared to German brutality in Southwest Africa (modern day Namibia), where German troops violently suppressed a Herrero uprising between 1904 and 1907, then banned the indigenous people from their own country.49

Germany congealed as a nation in January 1871, following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Germany’s industrial revolution proceeded rapidly thereafter, providing the economic basis for building a powerful army and navy. France, the loser in the Franco-Prussian War, greatly resented ceding the Alsace and Lorraine regions to Germany. Thereafter, French leaders embarked on a militarization program that conscripted all men between 20 and 40 years of age for five years of military service. “For the next 30 years,” writes the historian Gordon Martel, “France consistently spent more money on its army than Germany did, and at least twice as much on its navy. By 1900, France’s regular army was slightly larger than Germany’s.”50

Russia also sought to counter the military potential of Germany as well as that of Austria-Hungary. In November 1913, Czar Nicholas II adopted a “Great Military Programme” that called for a 40 percent increase in the size of the standing army over the next four years, and an expansion of the nation’s railway network, made possible by French loans, in order to facilitate rapid mobilization of troops. “One ironic outcome of the Russian undertaking,” notes Martel, “was to encourage those strategists in Germany who advocated a ‘preventative’ war.”51 Given the amount of time it took to organize, equip, and move troops to the front, the nation that mobilized its army first would gain great advantage in a war; hence, the German government’s view of the Russian mobilization as an act of war in August 1914.

In the decade prior to the Great War, Great Britain and Germany engaged in a naval arms race. Kaiser Wilhelm II was a disciple of Alfred Thayer Mahan, the American author of The Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1890). Mahan identified sea power as the single most important ingredient of a nation’s foreign policy, viewing Great Britain as the model naval power. The impetus for Germany’s naval buildup came in 1897 when the British Foreign Office threatened to blockade the German coast if Germany provided assistance to the Dutch Boers in South Africa. The following year, Germany undertook an aggressive program to build a fleet matching that of Great Britain. The British government responded with a buildup of its own, in keeping with its “two-power standard” that required the Royal Navy to be at least the size of the next two largest navies combined.

Such arms races were stimulated by advances in weapons technology. Machine guns, first manufactured in the 1880s, became lighter and more lethal, their capacity increasing to 500 rounds per minute by 1914, then to over 1,000 rounds per minute by 1918. Long-range artillery was developed and produced, such as the French 75, that could fire shells some twenty miles in distance. The British construction of the HMS Dreadnought in 1906, a huge armored battleship, prompted Germany to follow suit. When war came in 1914, Britain had twenty Dreadnoughts and Germany had thirteen. Germany countered Britain’s superiority on the high seas with torpedo-firing submarines, which fundamentally changed the nature and rules of naval warfare. A new terror emerged as the magnificent invention of the airplane was fitted with bombs and machine guns for assaults from the air. Most terrifying was the use of poison gas, despite agreement among the great powers at the Hague conference of 1907 to prohibit its use.

Each nation had its geopolitical objectives prior to the Great War. Germany wanted to expand its global economic influence and establish its “rightful” place in the sun as a great imperial power, expanding its colonies in Africa and Asia and possibly its European land mass. France wanted the return of the Alsace-Lorraine region from Germany and possibly the dismemberment of Germany in order to permanently end Germany’s military threat. Great Britain wanted to end Germany’s challenge to its naval supremacy, secure a stable balance of power on the European continent (no single dominant nation), and extend its empire in the Middle East. Russia wanted a warm water port on the Black Sea, possibly Constantinople, access to the Turkish straits, and more influence in the Balkans as the self-proclaimed protector of Slavic peoples. Austria-Hungary similarly wanted greater influence in the Balkans, including the incorporation of Serbia into its empire. Italy wanted parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Ottoman Empire wanted to keep what it had, especially against British and French encroachment.

Ideas and propaganda

The quest for military superiority and empire was underpinned by Social Darwinist ideas that permeated European and American intellectual culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Charles Darwin’s evolutionary concepts were applied, or misapplied, to human societies so as to justify racism, imperialism, militarism, and free market capitalism, all of which were said to conform to the “natural order” of life. The phrase “survival of the fittest” was coined by British philosopher Herbert Spencer in 1864.52 Fifty years later, in December 1914, former American president Theodore Roosevelt delivered a paper to the American Sociological Congress, writing that “every expansion of a great civilized power means a victory for law, order, and righteousness,” and that peace would come to the world only through “the warlike power of a civilized people.”53

In Germany, General Friedrich von Berhhardi similarly viewed war as a necessary agent of civilized “progress.” In his book, Germany and the Next War (1911), the 65-year-old general wrote, “War is not merely a necessary element in the life of nations, but an indispensable factor of culture, in which a true civilized nation finds its highest expression of strength and vitality. . . . Without war, inferior or decaying races would easily choke the growth of healthy budding elements, and a universal decadence would follow.”54

Berhhardi’s book turned out to be the perfect fodder for British propaganda, as the threat of German militarism was used to justify their own. Just 6,000 copies of Bernhardi’s book were printed in Germany, notes the historian Justus D. Doenecke, and “they made little impression on ordinary Germans. In 1912, the British translated the volume and, when war erupted, circulated it widely” in both Britain and the United States in order to prove the malicious intentions of “the Huns.”55

In the propaganda battles that accompanied the Great War, each side painted its own military policies as protective and noble in intent, whereas the rival power’s military policies were denounced as aggressive and evil in design. While the Allied Powers stood on firmer ground as far as self-defense justifications were concerned, all sought to advance their empires. Beyond defending one’s nation, war was also touted in all nations as a proving ground for manhood and a pathway to heroism. The British were alone among the European powers in not establishing a system of conscription (until the spring of 1916); hence the government produced a prodigious amount of propaganda aimed at encouraging or shaming young men to join the British Expeditionary Forces. Attacks on the home front, such as the German bombardment of Scarborough on December 16, 1914, greatly aided recruitment efforts.

Another use of propaganda was to undermine the enemy’s will to fight, whether by predicting the enemy’s eventual loss or by encouraging rebellions by dissatisfied minorities. Great Britain encouraged Arabs in the Ottoman Empire to join British forces, playing up Turkish oppression and promising independent Arab states after the war. Germany, meanwhile, encouraged the Ottoman sultan to declare jihad, or holy war, against the “infidel” British who established a protectorate over Egypt in 1914.

Great power diplomacy and cooperation

Although the great powers avidly competed with one other for military advantage, colonies, resources, and markets, they also engaged in diplomatic negotiations and bargained with each other to forestall war. Wars, after all, were costly in terms of blood and treasure, and they incurred risks for rulers: citizens and subjects might find the costs intolerable and overthrow the regime (as happened in Russia in 1917); ethnic-national groups might seek independence in the throes of war (as Irish rebels did in Great Britain in 1916); and other empires might take territory or force submission if the war was lost (as happened to the Central Powers). Diplomacy, in many instances, was the safer bet. In 1911, Great Britain mediated a showdown between France and Germany over control of Morocco; in the end, France retained control of Morocco (the Moroccans had no say) and Germany received two slices of the French Congo (the Congolese similarly were given no voice).

Diplomacy sometimes entailed forming alliances with other powers, whether for protection against attack or for mutual gain. In 1879, Germany and Austria-Hungary formed a Dual Alliance. Three years later, Italy joined the two, making it a Triple Alliance. In 1894, France and Russia established an alliance as a counterweight to the latter. Although Great Britain competed with France for colonies in Africa, and with Russia for spheres of influence in Asia, it nonetheless relied on these two states as counterweights to the Triple Alliance and thus signed an entente with France in 1904, and one with Russia in 1907. The competing alliances were designed to deter war, but instead they turned Europe into a powder keg waiting to ignite.

The underlying problem was not the balance-of-power alliance system per se, but rather the grasping states seeking territory or dominant influence in regions. Serbia, Greece, Romania, and especially Austria-Hungary all sought to expand their borders. In 1908, Russia reluctantly allowed Austria-Hungary to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina (located next to Serbia). In 1914, however, Russia refused to allow Austria-Hungary to take over Serbia. Mobilizations took place, the alliances kicked in, and world war erupted in a flash.

The period before the Great War also saw times when the great powers cooperated in their imperial pursuits. In the winter of 1884-85, representatives of twelve European states and the Ottoman Empire met in Berlin to jointly carve up the African continent into colonies. Clear territorial boundaries, it was understood, would serve to avoid conflicts between the colonizers, allowing them to concentrate on exploiting their assigned regions. Always seeking noble rationales to justify imperialism and aggression, the colonizers declared their intention to end Islamic and African slavery as part of their civilizing missions.

Another point of cooperation was the Open Door policy toward China, first put forth by Great Britain in 1898.56 This tenuous agreement stipulated that all of the major powers, including the United States, would have equal trading rights in China and that China itself would remain whole. The policy was designed to prevent one great power from dominating China and to prevent wars among the imperial powers. When, in 1900, Chinese nationalists pushed back against foreign domination in the Boxer Rebellion, the imperial powers (Great Britain, France, the United States, Germany, Russia, and Japan) organized a joint expeditionary force of 20,000 soldiers to suppress it.

Such manifestations of cooperative Pax Imperium encouraged some imperialists as well as some peacemakers to believe that a permanent alliance of great power interests could provide the basis for a stable peace. Andrew Carnegie, the American steel magnate and philanthropist, gave an address in 1905 in which he proposed a “League of Peace” that would establish arbitration mechanisms to curb “the crime of destroying human life by war.” The fact that six great powers had “cooperated in quelling the recent Chinese disorders and rescuing their representatives in Peking” gave him hope that the great nations “could banish war.”57 One manifestation of this melding of power-elitism and peacemaking was The Hague Peace Convention of 1899, which established a Permanent Court of Arbitration. The court, notes the historian Robert E. Hannigan, “was principally designed to stabilize the status quo.”58 The idea of a permanent international association, the League of Nations, was similarly envisioned as a means of stabilizing the world order, perhaps modifying it but not overthrowing it.

One of the great ironies of European power struggles was that the European royalty was connected by marriage and family. England’s King George V was the first cousin of Czar Nicholas II of Russia on his mother’s side, the two looking like twin brothers, and the first cousin of Kaiser Wilhelm II on his father’s side. As children, the three future monarchs played together on holiday excursions. Czar Nicholas was married to a German-born princess, Alexandra Feodorovna. He named Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany as godfather to one of his children. Both Nicholas and Wilhelm were at the bedside of their grandmother, Queen Victoria of England, when she died. Royal etiquette and diplomacy continued as the crisis over Serbia unfolded in mid-1914. According to Adam Hochschild:

In late June, a squadron of British battleships and cruisers were welcome guests at Germany’s annual Elbe Regatta. Loving medals and epaulets as much as ever, the Kaiser proudly donned his gold braid as an honorary British admiral of the fleet, and British and German officers attended races and banquet together. When the Royal Navy warships weighed anchor and sailed for home, their commander signaled his German counterpart: “Friends in past, and friends forever.” And why not?59

European Peace Activism (…)

Read on…

__________________________________________________

The purpose of this commercial-free educational website is to provide an accessible, accurate, principled, and resource-rich history of United States foreign policy. The website was launched in October 2015 by Roger Peace, author of the Home page. The Historians for Peace and Democracy became a sponsor the following month, and the Peace History Society, in June 2016. The Historians for Peace and Democracy (formerly Historians Against the War) was founded in 2003 in opposition to the Iraq War. “As historically minded activists, scholars, students, and teachers, we stand opposed to wars of aggression, military occupations of foreign lands, and imperial efforts by the United States and other powerful nations to dominate the internal life of other countries.” The Peace History Society is dedicated to peace research and education. “The Peace History Society was founded in 1964 to encourage, and coordinate national and international scholarly work to explore and articulate the conditions and causes of peace and war, and to communicate the findings of scholarly work to the public.”

To continue reading Go to Original – peacehistory-usfp.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

HISTORY:

- History of US-Iran Relations: From the 1953 Regime Change to Trump Strikes

- Digging Up the Roots of Human Culture

- The Geopolitics of Southeast Europe and the Importance of the Regional Geostrategic Position at the Turn of the 20th Century

ANGLO AMERICA:

- Washington Green-Lights $30M for Gaza Aid Scheme Tied to Mass Killings of Palestinians

- War with Iran: We Are Opening Pandora's Box

- Trump’s Useful Idiots

MILITARISM:

- The Transatlantic Split Myth: How U.S.-Europe Militarization Thrives behind the Rhetoric

- Mapping Militarism 2025

- The Limitations of Military Might

EUROPE: