D.H. Lawrence on the Antidote to the Malady of Materialism

INSPIRATIONAL, 28 Oct 2019

Maria Popova | Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Owners and owned, they are like the two sides of a ghastly disease. One feels a sort of madness come over one, as if the world had become hell. But it is only superimposed: it is only a temporary disease. It can be cleaned away.”

“It is now the most vitally important thing for all of us… to try to arrive at a clear, cogent statement of our ills, so that we may begin to correct them,” the Trappist monk Thomas Merton wrote in his touching fan letter to biologist Rachel Carson after she awakened the modern environmental conscience with her courageous 1962 book Silent Spring — a sobering look at the consequences, both for humanity and for our fragile planet, of material greed, unbridled power, and the cultural machine of consumerism. Several years later, the German humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm further diagnosed the central malady of materialism in his pioneering treatise on the tradeoffs between having and being:

“It is now the most vitally important thing for all of us… to try to arrive at a clear, cogent statement of our ills, so that we may begin to correct them,” the Trappist monk Thomas Merton wrote in his touching fan letter to biologist Rachel Carson after she awakened the modern environmental conscience with her courageous 1962 book Silent Spring — a sobering look at the consequences, both for humanity and for our fragile planet, of material greed, unbridled power, and the cultural machine of consumerism. Several years later, the German humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm further diagnosed the central malady of materialism in his pioneering treatise on the tradeoffs between having and being:

“The full humanization of man requires the breakthrough from the possession-centered to the activity-centered orientation, from selfishness and egotism to solidarity and altruism.”

But because the epidemiology of disease parallels that of ideas, by the time symptoms arise, the illness has been silently working its way through the body of culture for generations.

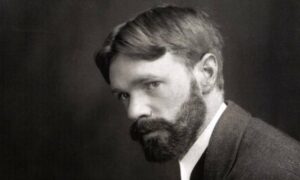

Half a century before Carson and Fromm, and decades before the golden age of consumerism, the English poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, and painter D.H. Lawrence (September 11, 1885–March 2, 1930) pressed his prescient fingers against the pulse-beat of culture to limn the malady that would define the century to come — the greed for power and material possession that would give rise to numerous dictatorships, exploit vulnerable populations, and deplete Earth’s resources — and envisioned a remedy it is not too late for us to implement.

Just before his thirtieth birthday in the summer of 1915, while escaping the tumult of World War I at the English seaside resort of Littlehampton, Lawrence contemplated the relationship between the increasingly artificial human world and the immutable authenticity of the natural world in a letter to his friend Lady Cynthia Asquith, found in The Letters of D.H. Lawrence (public library). Echoing Whitman (“After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains? Nature remains.”), Lawrence writes:

We have lived a few days on the seashore, with the wave banging up at us. Also over the river, beyond the ferry, there is the flat silvery world, as in the beginning, untouched: with pale sand, and very much white foam, row after row, coming from under the sky, in the silver evening: and no people, no people at all, no houses, no buildings, only a haystack on the edge of the shingle, and an old black mill. For the rest, the flat unfinished world running with foam and noise and silvery light, and a few gulls swinging like a half-born thought. It is a great thing to realise that the original world is still there — perfectly clean and pure…

Half a century before E.F. Schumacher made his elegant anti-consumerist case for “Buddhist economics,” Lawrence contrasts this living Paradise with the human-made inferno of materialism — an inferno whose blazing fire of greed and fuming brimstone of ownership have only intensified in the century since.

Art by JooHee Yoon from The Tiger Who Would Be King, James Thurber’s 1927 parable of the destructiveness of greed and unbridled power.

Lawrence, who was a vocal opponent of militarism despite how unpopular and downright anti-patriotic this rendered him in wartime Britain, no doubt saw the causal relationship between humanity’s growing hunger for material possession —

the ultimate end of power — and the first truly global war that had just engulfed the world. He writes:

It is this mass of unclean world that we have superimposed on the clean world that we cannot bear. When I looked back, out of the clearness of the open evening, at this Littlehampton dark and amorphous like a bad eruption on the edge of the land, I was so sick I felt I could not come back: all these little amorphous houses like an eruption, a disease on the clean earth; and all of them full of such diseased spirit, every landlady harping on her money, her furniture, every visitor harping on his latitude of escape from money and furniture. The whole thing like an active disease, fighting out the health. One watches them on the sea-shore, all the people, and there is something pathetic, almost wistful in them, as if they wished that their lives did not add up to this nullity of possession, but as if they could not escape. It is a dragon that has devoured us all: these obscene, scaly houses, this insatiable struggle and desire to possess, to possess always and in spite of everything, this need to be an owner, lest one be owned. It is too horrible. One can no longer live with people: it is too hideous and nauseating. Owners and owned, they are like the two sides of a ghastly disease. One feels a sort of madness come over one, as if the world had become hell. But it is only superimposed: it is only a temporary disease. It can be cleaned away.

Sixteen years before his polymathic compatriot Bertrand Russell admonished against letting power-knowledge eclipse love-knowledge, Lawrence considers what it would take to rehabilitate the human spirit and treat not the symptoms but the illness itself:

One must destroy the spirit of money, the blind spirit of possession. It is the dragon for your St. George: neither rewards on earth nor in heaven, of ownership: but always the give and take, the fight and the embrace, no more, no diseased stability of possessions, but the give and take of love and conflict, with the eternal consummation in each. The only permanent thing is consummation in love or hate.

Complement this fragment of the immeasurably beautiful Letters of D.H. Lawrence with Alan Watts on money vs. wealth, Henry Miller on how the hedonic treadmill of materialism entraps us, and E.F. Schumacher on how to begin prioritizing people over products and creativity over consumption, then revisit Whitman on what makes life worth living.

_______________________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

Tags: Capitalism, Inspirational, Materialism

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.