Deathly Silence: An Inside Look at Kashmir

BRICS, 18 Nov 2019

Laura Höflinger and Sunaina Kumar – Der Spiegel

Kashmir has been largely cut off from the outside world for months and the internet remains cut off. Residents share stories of state violence and terror.

15 Nov 2019 – The first thing that comes as a surprise to a visitor is just how quiet it is. You can see people on the streets, but shops and offices are all closed. Officially, the schools are open, but the classrooms are largely empty because many boys and girls stay home out of fear. Someone has painted the message “We exist to resist” on the shutter of a shopfront.

The Indian government insists that the situation in Kashmir is returning to normal. Or at least what could be considered normal in a region where roads are blocked with sandbags and barbed wire, where passerby are monitored by soldiers in bunkers and where more than 400 people lost their lives last year due to terrorism and state violence.

Three months have now passed since India revoked the special status granted to its part of Kashmir. Earlier this month, the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the further step of dividing the once semi-autonomous state into two federal territories and placing them under the control of New Delhi.

Hundreds of politicians were arrested and remain behind bars. India had offered them freedom, but only if they agreed to refrain from speaking about the revocation of Kashmir’s autonomy for an entire year. Foreigners and Indian opposition leaders have been banned from traveling to Kashmir. The first foreigners allowed to enter the region recently were 23 members of the European Parliament, who visited in late October. Most were members of right-wing populist parties, including from the Alternative for Germany party.

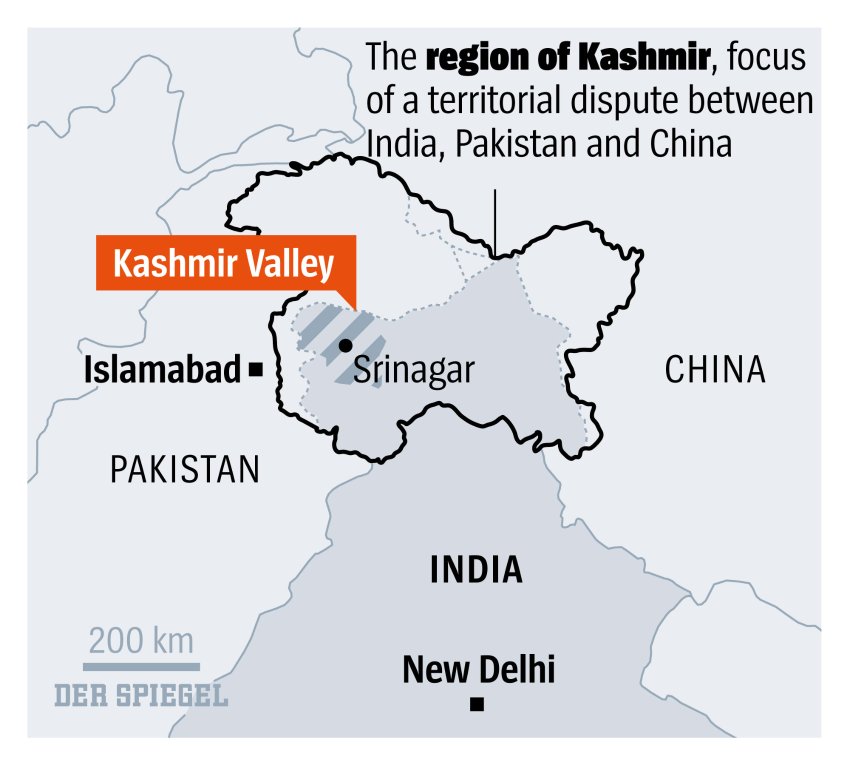

The Kashmir conflict has generated less attention in Europe than the protests in Hong Kong, yet it is the far more dangerous of the two crises. India, Pakistan and China all lay claim to a part of Kashmir, meaning three nuclear powers are playing tug-o’-war over the region. Pakistan has already warned about potential consequences, while the Indian defense minister has said that India would stick to the No First Use doctrine when it comes to using nuclear weapons, but what happens in the future would depend on circumstances.

Very little, however, has been heard from the people of Jammu and Kashmir themselves. After a weeks-long blackout imposed by New Delhi, landline and mobile telephones now work in the region once again. But the internet is still shut down.

DER SPIEGEL has met with more than a dozen people in Kashmir, and their reports are shocking and sometimes contradictory. Some fear the Indian state. Others are hoping for protection. All, however, are afraid of what may be on the horizon. One says: “We are experiencing the calm before the storm.”

‘I’m Cold, Even When the Sun is Shining’

There’s a village full of broken windowpanes in southern Kashmir. Residents say soldiers throw stones through the windows at night, and claim fearful residents switch off their lights after sundown and barricade themselves in the darkness of their homes.

Almost nobody in the town is willing to speak openly with journalists. There is a strong atmosphere of paranoia, with many apparently wondering if the foreigner really is who she says she is — and not a spy.

The woman who finally does invite us into her home declines to provide her real name. She is 44 years old, wears a headscarf and asks to be identified as Sakina. When talking about her son, she breaks down repeatedly. She shows a photo of a young man of around 20 with long black hair and a beard.

“It was the night of August 7. We could hear noise from outside, but we were too afraid to see what was going on. Instead, we went to bed, my daughter and I slept in the kitchen and my father and my son in a room at the front of the house. It must have been around three in the morning when five or 10 soldiers began hammering on our door.

They stormed into my son’s room and pulled him out of bed. We wanted to know what he had done and where they were taking him. But we didn’t get an answer. The soldiers locked us in and fired two shots. One of the shots hit the ground right here by the door, I can show you the spot. Since my son has been gone, I feel numb. I’m cold and I shiver, even when the sun is shining. The army forced its way into my home and took away my child.”

Sakina’s son wasn’t the only one arrested by the soldiers. In the days both before and after Kashmir’s autonomy was revoked, the army arrested men they considered potential troublemakers. According to reports, a total of more than 4,000 were taken into custody. Some were flown out of the region. Sakina’s son is locked up in Agra, a city in northern India located around 700 kilometers (400 miles) away.

Two laws have essentially given security forces a free hand. According to the Public Safety Act, people in Kashmir can be held in custody for up to two years without trial, while the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act gives soldiers de facto immunity. There have been numerous, serious allegations made against the army, including rape, torture and murder. But according to the human rights organization Amnesty International, not a single member of the security forces has yet had to answer for them before a civilian court.

“You Just End Up Firing”

On 90 Feet Road, an upscale residential district in Srinagar, Kashmir’s summer capital, a man is dressed for battle. He is wearing a bulletproof vest and carrying an AK-47, a truncheon and a shield. He’s a member of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), a paramilitary force under the command of the Interior Ministry in Delhi. Nearly half-a-million security forces are said to be currently stationed in Kashmir, making the region one of the most militarized areas in the entire world.

Kashmiris say they would rather dodge traffic on the side of the road than walk past the troops on the sidewalk. The guy from CRPF comes from a town near Delhi, and every time someone passes by, his shoulders tense up.

“When I heard that the region’s autonomous status was to be revoked, I had a sense of dark foreboding. I have seen the worst of times in Kashmir, but I am surprised by how peaceful it has been . Kashmir is one of the most difficult postings of all. It takes no time for a crowd to collect here and before you know it, 250 people are running toward you . We can’t trust the people here. Even the old ones and the young ones tend to be radicalized .

We do our best not to injure anyone; we use our guns only as a last resort and are trained to aim below the knee. But when you are surrounded by a furious mob, you just end up firing .

Even those two boys there on the bike can be a threat. They could throw stones or a grenade. How can you not get angry or not want to take revenge? We are doing our duty and they are throwing stones at us. We always stand together in pairs to give each other cover, but never in groups so that we don’t become easy targets.”

Kashmir is one of the world’s large unsolved conflicts, and is extremely complicated. The former state is essentially divided into three parts. There is the largely Hindu Jammu, with 6 million residents, and the Buddhist-dominated mountainous area of Ladakh, with a population of around 300,000. But when people speak of Kashmir, they are usually — as is the case in this story — referring to the Kashmir Valley, the epicenter of the conflict, where 8 million, mostly Muslim, people live.

This is where the Kashmiri Insurgency began in 1989. At the time, some demonstrators demanded independence from India, while others insisted on being annexed to Pakistan. Security forces fired tear gas and deployed deadly force, but the more harshly India responded, the more support militant groups received, in part thanks to support from Pakistan, which also controls a part of the region and also lays claim to all of it. The Pakistani secret service trained and armed fighters. Ultimately, 40,000 people lost their lives in the fighting.

Older Kashmiris say they were convinced at the time that their protests would bring about change. Now, 30 years later, such hopes have largely been dashed.

Instead, the insurgency grew increasingly brutal and extremist in nature. Islamists drove most of the hundreds of thousands of people who belonged to the Hindu minority out of the valley. Only around 3,000 of them remain today. One extremist declared by video three years ago that he was fighting for the establishment of a caliphate. His death triggered mass protests, partly fueled by social media, in which many people lost their lives. The Indian government argues that if it doesn’t take a tough enough approach, people will start dying once again.

‘India is a Good Country’

The market in Drabgam is essentially dead. Only a single military vehicle is parked nearby. Tanveer Ahmed Dar, a farmer, is sitting in the shade of a tree while a couple of seasonal workers pick apples nearby. Most of the fruit, though, lies rotting in the grass. First, it was his income that was endangered, Dar says. Now, it’s his life.

Tanveer Ahmed Dar: “Ever since militants began shooting truck drivers, I can’t find anyone willing to transport my apples.” Kumar Sunaina/ DER SPIEGEL

“We are working against time. Every day, I lose 20 crates of apples, that’s 20,000 rupees (around 250 euros). We aren’t even able to pack the apples properly. As soon as the sun goes down, we hurry home because it’s not safe out here. There are rumors that militants are destroying food stocks and I’ve also heard about an apple orchard being sprayed with chemicals to destroy it.

The government promised us a good price for our apples, but can they also guarantee our safety? Ever since militants began shooting truck drivers, I can’t find anyone willing to transport my apples. Those who suffer are the ordinary citizens who can do nothing. Why is this happening to us? We believe that India is a good country. I see myself as Indian.”

Around 3.5 million people depend on the annual apple harvest. But the communications blockade hampered business, and now the farmers have to live in fear of the militant fighters.

A few weeks ago, posters began appearing on power poles and on the walls of buildings and mosques. They were essentially death threats to all those who dared return to their normal lives, a threat underlined by several recent and deadly attacks on truck drivers and apple farmers. Extremists also threw a grenade into a market filled with civilians.

There are analysts in Delhi who believe that Modi’s move to revoke autonomy was genius in that it provided a clear answer on the question of independence and sent a tough message to both Pakistan and China.

China controls a fifth of the region. As part of the New Silk Road Initiative, China’s multibillion-dollar development program, Chinese companies are building roads through the Pakistan-controlled section of Kashmir. India feels surrounded by its two neighbors.

A second interpretation holds that India has now made it easier for all those aiming to foster unrest in Kashmir. After all, one of the main lessons from Kashmir’s history is that whenever New Delhi has believed it could solve a political crisis with military means, it has provoked a fresh wave of violence.

‘It is an Occupation’

Zabirah Fazili, a 24-year-old university student who studies literature, lives with her family in a house in Srinagar. Normally, she vents her emotions on Facebook, but with the internet shut down, she has very little contact with the outside world. She takes medication to help her post-traumatic stress disorder, which stems from her experiences with terror and violence. At the hospital, doctors say anxiety disorders are on the rise.

Zabirah Fazili’s family became more widely known in the region after her cousin Eisa Fazili was killed in a firefight. Thousands of people came to his funeral, with radicals spreading the black flag of Islamic State across his body. The family first learned from the internet that Eisa had joined a radical group.

Zabirah Fazili: “I don’t shun the idea of militancy.”

Kumar Sunaina’s interview partner: Tanveer Ahmed Dar, Kashmir, Oktober 2019

“Eisa and I were the same age. We were close. It was a shock when he suddenly disappeared. I don’t shun the idea of militancy. I don’t think the intellectual struggle is doing much at the moment. I have two younger brothers and if the Indian army attacks them, I would understand if they were to become radicalized.”

In Srinagar, there have always been two camps. One demands independence from India, with some being prone to violence. The other is more moderate, with its followers perhaps not feeling Indian, exactly, but valuing the opportunities the country has made possible. The question now is how many of the latter camp, after months of imperiousness from New Delhi, still see India as their homeland.

Perhaps Modi’s hardline approach will ultimately prove successful. Perhaps, he’ll manage to do in Kashmir what he has thus far failed to do in the rest of India: revive the economy and reconcile the population. At the moment, though, it seems unlikely.

Tags: Asia, Asia and the Pacific, BRICS, Conflict, Culture, Geopolitics, Hinduism, History, Human Rights, India, Indigenous Rights, International Relations, Islam, Kashmir, Nuclear Weapons, Nuclear war, Occupation, Pakistan, Politics, Power, Religion, Social justice, Solutions, State Terrorism, Terrorism, UN, Violence, War, World

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.