Marx and the Expropriation of Nature

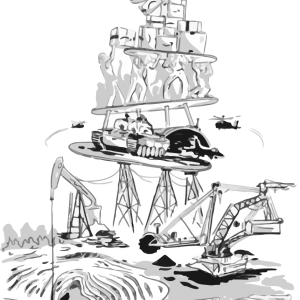

The notion of “extractive industry” dates back to Marx in the mid-nineteenth century. He divided production into four spheres: extractive industry, agriculture, manufacturing, and transport. Extractive industry was seen by him as constituting the sector of production in which “the material for labour is provided directly by Nature, such as mining, hunting, fishing (and agriculture, but only insofar as it starts by breaking up virgin soil).”19 In general, Marx drew a line between extractive industry and agriculture, insofar as the latter was not dependent on raw materials from outside agriculture, but was capable of building up from within, given agriculture’s reproductive, as opposed to nonreproductive, characteristics. This, however, did not prevent him, in his theory of metabolic rift, from seeing capitalist industrial agriculture as expropriative, and in ways that we now call extractivist.

Some of Marx’s most critical comments with regard to the capitalist mode of production are directed at mining as the quintessential extractive industry. In his discussion of coal mining in the third volume of Capital, he treats the absolute neglect of the conditions of the coal miners, resulting in an average loss of life of fifteen people a day in England. This led him to comment that capital “squanders human beings, living labour, more readily than does any other mode of production, squandering not only flesh and blood but nerves and brains as well.”20 But the destructive effects of extractive industry and of capital in general, for Marx, were not restricted to the squandering of flesh and blood, but also extended to the squandering of raw materials.21 Moreover, Engels, in writing to Marx, famously discussed the “squandering” of fossil fuels, and coal in particular.22

In interviews that he gave responding to radical and Indigenous movements against extractivism, Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa rhetorically asked: “Let’s see, señores marxistas, was Marx opposed to the exploitation of natural resources?” The implication was that Marx would not have opposed contemporary extractivism. In response, ecological economist Joan Martinez-Alier pointed to Marx’s famous analysis indicating that “capitalism leads to a ‘metabolic rift.’ Capitalism is not capable of renewing its own conditions of production; it does not replace the nutrients, it erodes the soils, it exhausts or destroys renewable resources (such as fisheries and forests) and non-renewable ones (such as fossil fuels and minerals).” On this basis, Martínez-Alier contends that Marx, though he did not live to see global climate change, “would have sided with Climate Justice.”23 Indeed, the extraordinary growth of the Marxian ecological critique, building on Marx’s analysis in Capital of the “negative, i.e., destructive side” of capitalist production in his theory of metabolic rift, has provided the world with penetrating insights into every aspect of the contemporary planetary crisis.24

Not only was the expropriation of land and bodies recognized in Marx’s analysis, but the earth itself could be expropriated in the sense that the conditions of its reproduction were not maintained, and natural resources were “robbed” or “squandered.”

Key to a historical-materialist analysis of extractivism is Marx’s analysis of what he called “original expropriation,” a term that he preferred to what the classical-liberal political economists called “previous, or original accumulation” (often misleadingly translated as “primitive accumulation”).25 For Marx, “so-called primitive [original] accumulation,” as he repeatedly emphasized, was not accumulation at all, but rather expropriation or appropriation without equivalent.26 Taking a cue from Karl Polanyi—and in line with Marx’s argument—we can also refer to expropriation as appropriation without reciprocity.27 Expropriation was evident in the violent seizure of the commons in Britain. But “the chief moments of [so-called] primitive accumulation” in the mercantilist era, providing the conditions for “the genesis of the industrial capitalist,” lay in the expropriation of lands and bodies through the colonial “conquest and plunder” of the entire external area/periphery of the emerging capitalist world economy. This was associated, Marx wrote, with “the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the Indigenous population” in the Americas, the whole transatlantic slave trade, the brutal colonization of India, and a massive drain of resources/surplus from the colonized areas that fed European development.28

Crucial to this analysis was Marx’s very careful distinction between appropriation, understood in its most general sense as the basis of all property forms and all modes of production, and those particular forms of appropriation, such as for-profit expropriation and wage-based exploitation that characterized the regime of capital. Marx conceived appropriation in general as rooted in the free appropriation from nature, and thus as a material prerequisite of human existence, leading to the formation thereby of various forms of property, with private property constituting only one such form, which became dominant only under capitalism. This general historical theoretical approach gave rise to Marx’s concept of the “mode of appropriation” underlying the mode of production.29 These distinctions were to play an important role in his later ethnological writings, and his identification with the active resistance to the expropriation of the lands of Indigenous communities in Algeria and elsewhere.30

Not only was the expropriation of land and bodies recognized in Marx’s analysis, but the earth itself could be expropriated in the sense that the conditions of its reproduction were not maintained, and natural resources were “robbed” or “squandered.”31 This was particularly the case with capitalism, in which the appropriation of nature generally took a clear, expropriative form. In Marx’s analysis, the free appropriation of nature by human communities, constituting the basis of all production, was seen as having metamorphosed under capitalism into the more destructive form of “a free gift of Nature to capital,” no longer geared primarily to the reproduction of life, the earth, and community as one ultimately indivisible whole, but rather dedicated solely to the valorization of capital.32 The robbery of the earth and the metabolic rift—or the “irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism” between humanity and nature—were thus closely interwoven.33 Although some contemporary theorists have attempted to define extractivism as meaning simply the nonreproduction of nature, it is more theoretically meaningful to view this in line with Marxian ecology in terms of what Marx called the robbery or expropriation of nature, of which extractivism is simply a particularly extreme and crucial form.

Gudynas and the Extractivist Surplus

These conceptual foundations arising out of Marx’s classical ecological critique allow us to appreciate more fully the pathbreaking insights into extractivism provided by Gudynas in his recent book, Extractivisms. A crucial point of departure in his analysis is the concept of modes of appropriation. In his pioneering 1985 work Underdeveloping the Amazon, environmental sociologist Stephen G. Bunker introduced the notion of “modes of extraction” to address the issue of extractive industry and its nonreproductive character, contrasting this to Marx’s larger concept of “modes of production.”34 Gudynas claims that Bunker was generally on the right track. However, in contrast to Bunker, Gudynas does not adopt the category of modes of extraction. Nor does he retain Marx’s notion of modes of production, arguing unaccountably that Marx’s concept has been “abandoned,” citing anthropologist and anarchist activist David Graeber. Rather, Gudynas turns to the concept of “modes of appropriation,” while seemingly unaware of the theoretical connection between appropriation and production and between modes of appropriation and modes of production that Marx had constructed in the Grundrisse, and how this is related to current Marxian research into these categories.35 Still, Gudynas’s modes-of-appropriation approach allows him to distinguish between human appropriation from the natural environment in general and what he refers to as “extractivist modes of appropriation,” which violate conditions of natural and social reproduction.

Gudynas defines extractivism itself in terms of processes that are excessive as measured by three characteristics: (1) physical indicators (volume and weight), (2) environmental intensity, and (3) destination, with extractivism seen as inherently related to colonialism and imperialism, requiring that the product be exported in the form of primary commodities.36 Not all appropriation of nature carried out by extractive industries is extractivist. This is perhaps clearest in his short piece, “Would Marx Be an Extractivist?” As in Martínez-Alier’s response to Correa, Gudynas states:

Marx did not reject mining. Most of the social movements do not reject it, and if their claims are heard carefully, it will be found that they are focused on a particular kind of enterprise: large scale, with huge volumes removed, intensive and open-pit. In other words, don’t confuse mining with extractivism…. Marx, in Latin America today, would not be an extractivist, because that would mean abandoning the goal of transforming the modes of production, becoming a bourgeois economist. On the contrary, he would be promoting alternatives to [the dominant mode of] production, and that means, in our present context, moving toward post-extractivism.37

Today’s global extractivism, what Martin Arboleda has called The Planetary Mine, is identified with “generalized-monopoly capital” and conditions of “late imperialism.”38 A central concern of Gudynas’s work is a critique of the renewed imperial dependency in the Global South resulting from neo-extractivism, raising the question of “delinking from globalization” as perhaps the only radical alternative.39 A similar view was powerfully developed by James Petras and Henry Veltmeyer in their Extractive Imperialism, which described the new extractivism as a new imperialist model, forcing countries into a new dependency, the ground for which had been prepared by the neoliberal restructuring that virtually annihilated many of the earlier forces of production in agriculture and industry.40

Gudynas’s signal contribution, however, lies in his attempt to connect extractivism to the concept of surplus in order to explain the economic and ecological losses associated with the reliance on extractivist modes of appropriation. Here, he relies on the concept of economic surplus developed by Paul A. Baran in The Political Economy of Growth in the 1950s, which was designed to operationalize Marx’s surplus value calculus in line with a critique that had rational economic planning as its yardstick.41 Gudynas notes that in Baran’s concept of economic surplus, in conformity with Marx’s surplus value, “ground rent and interest on money capital” are components of total surplus rather than production costs. In introducing the concept of economic surplus, Baran sought to reveal what were, in capitalist accounting, essentially disguised forms, as Gudynas puts it, of the “appropriation of the surplus.”42

Employing this idea, Gudynas seeks to add to the economic or social dimension of surplus, based on the exploitation of labor, two environmental dimensions of the surplus in the context of extractivist modes of appropriation. The first of these, the environmental renewable surplus, is seen as related to the classic Ricardian-Marxian theory of agricultural ground rent focused primarily on renewable industry. It is meant to capture surplus not only associated with monopoly rents and thus integrated directly into the economic calculus, but also, according to Gudynas, to grapple with how ecosystem services such as pollination are extractively appropriated/expropriated. Gudynas indicates that a larger “monetized surplus” is created for corporations by neglecting such crucial environmental aspects as soil and water conservation, thus generating an artificially large surplus based on the extractivist appropriation of renewable resources. This is related to what Marx called the “robbing” or expropriation of the earth, part of his theory of metabolic rift.43

According to Gudynas, the third dimension of the surplus (the second environmental dimension) is the environmental nonrenewable surplus related to nonrenewable resources, such as minerals and fossil fuels. “The key distinction here,” he writes, “is that the resource will be exhausted sooner or later, and therefore the surplus captured by the capitalist will always be proportional to the loss of natural heritage that cannot be recovered. Similarly, the space occupied by a mining enclave will be impossible to use for another purpose, such as agriculture.” Whatever extractivist surplus is obtained has to be set against the loss of natural wealth associated with resource depletion, something that is disguised by the common employment of the concept of “natural capital,” conceived today not, as in classical political economy, in terms of use value, but rather, in accord with neoclassical economics, in terms of exchange value and substitutability.44 The current planetary ecological crisis has to be seen in terms of the generation of a destructive expropriation of nature, which needs to be transcended in the process of going beyond capitalism.

In Marx and Engels’s classical historical materialism, a very similar analytical approach was adopted with respect to the expropriation of nonrenewable resources to that presented by Gudynas in his analysis of the environmental nonrenewable surplus. For Marx and Engels, the destructive expropriation of nonrenewable resources could not be treated as a straightforward case of robbing, as in the case of the soil, forests, fishing, and so on. Hence, they approached extractivism with respect to nonrenewable resources under the rubric of the squandering of such resources, a concept that was especially used in relation to the avaricious expropriation of minerals and fossil fuels, particularly coal, but also applied to the extreme “human sacrifices” in extractivist industries, related to what is nowadays sometimes called the “corporeal rift.”45 Capitalism’s relation to both renewable and nonrenewable resources was thus seen in the classical historical-materialist perspective as pointing to the destructive expropriation of the earth, either as the “robbing” or the “squandering” of nature—an approach that closely corresponds to Gudynas’s two forms of extractivist surplus appropriation/expropriation.

Gudynas’s approach to what he calls the “extractivist surplus” associated with his two environmental dimensions of surplus is meant to encompass externalities, highlighting the fact that the “actual surplus” appropriated—to use Baran’s terms—is, in some cases, artificially high, in relation to a more rational “planned surplus,” as it does not account for depletion of fossil fuels and other natural resources.46 This basic approach is employed in the remainder of Gudynas’s analysis to engage with struggles on the ground over this bleeding of the extractivist economies and its relation to late imperialism, which carries out such bleeding on ever-larger scales to the long-term detriment of the relatively dependent peripheral or semiperipheral (that is, emerging) economies. As he argues in Extractivisms, this ultimately becomes a question of “extractivism and justice.”47

Extractivism and the Crisis of the Anthropocene

Given that the Anthropocene, though still not official, has been defined as that epoch in which anthropogenic rather than nonanthropogenic factors, for the first time in geological history, are the primary drivers determining Earth System change, it is clear that the Anthropocene will continue as long as global industrial civilization survives. The current Anthropocene crisis, defined as an “anthropogenic rift” in the biogeochemical cycles of the Earth System, is closely associated with the system of capital accumulation and is pointing society toward an Anthropocene extinction event.48 To avoid this, humanity will need to transcend the dominant “accumulative society” imposed by capitalism.49 But there will be no progressive escaping from the Anthropocene itself in the conceivable future, since humanity, even in an ecologically sustainable socialist mode of production, will remain on a razor’s edge, given the current planetary-scale stage of economic and technological development, and the fact that the limits of growth will need to be accounted for in the determination of all future paths of sustainable human development.

It was the recognition of these conditions that led Carles Soriano, writing in Geologica Acta, to propose the Capitalian as the name of the first geological age of the Anthropocene Epoch.50 According to this outlook, the current planetary ecological crisis has to be seen in terms of the generation of a destructive expropriation of nature, which needs to be transcended in the process of going beyond capitalism and the Capitalian Age. Others independently proposed the name Capitalinian for this new geological age, while also pointing to the notion of a Communian—standing for communal, community, commons—as the future geological age of the Anthropocene; one that needs to be created in coevolution with nature, necessitating a “great climacteric” by the mid-twenty-first century.51

In the present century, combating the capitalist expropriation of nature and in particular the extractivism that is more and more dominating our time—along with surmounting the present accumulative system itself—has to take priority at all levels and in all forms of social struggle. In the classical historical-materialist perspective, production as a whole—not simply extractive industry, but also agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation—needs to be confronted in order to transcend the contradictions of class-based capital accumulation. In this regard, the insights of the broad historical-materialist tradition are crucial. As Marx observed: “Since actual labour is the appropriation of nature for the satisfaction of human needs, the activity through which the metabolism between man and nature is mediated, to denude labour capacity of the means of labour, the objective conditions for the appropriation of nature through labour, is to denude it, also, of the means of life. Labour capacity denuded of the means of labour and the means of life is therefore absolute poverty as such.”52

With the growth of accumulation, denuding labor of its role as the direct mediator of the metabolism between humanity and nature, and substituting capital in this role through its control of the objective conditions of the appropriation of nature, has meant that the means of life on the planet are being destroyed. The only answer is the creation of a higher form of society in which the associated producers directly and rationally regulate the metabolism between humanity and nature, in accord with the requirements of their own human development in coevolution with the earth as a whole.

Notes

- ↩ On the Anthropocene, see Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Mark Williams, and Colin P. Summerhayes, The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019); Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- ↩ See Zalasiewicz, Waters, Williams, and Summerhayes, The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit, 256–57; Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, 44–45.

- ↩ Christoph Gorg et al., “Scrutinizing the Great Acceleration: The Anthropocene and Its Analytic Challenges for Social-Ecological Transformations,” Anthropocene Review 7, no. 1 (2020): 42–61.

- ↩ Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen, The Imperial Mode of Living (London: Verso, 2021).

- ↩ Alicia Bárcena Ibarra, United Nations Environmental Programme Press Release, “Worldwide Extraction of Materials Triples in Four Decades, Intensifying Climate Change and Air Pollution,” July 20, 2016.

- ↩ United Nations Environment Programme, Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity (2016), 5.

- ↩ World Trade Organization, Trade Profiles 2021. See also Martin Upchurch, “Is There a New Extractive Capitalism?,” International Socialism 168 (2020).

- ↩ Eduardo Gudynas, Extractivisms (Blackpoint, Nova Scotia: Fernwood, 2020), 82.

- ↩ Mark Bowman, “Land Rights, Not Land Grabs, Can Help Africa Feed Itself,” CNN, June 18, 2013.

- ↩ Guy Standing, “How Private Corporations Stole the Sea from the Commons,” Janata Weekly, August 7, 2022; Stefano Longo, Rebecca Clausen, and Brett Clark, The Tragedy of the Commodity (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2015).

- ↩ Vijay Prashad and Taroa Zúñiga Silva, “Chile’s Lithium Provides Profit to the Billionaires but Exhausts the Land and the People,” Struggle-La Lucha, July 30, 2022.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, “The Defense of Nature: Resisting the Financialization of the Earth,” Monthly Review 73, no. 11 (April 2022): 1–22.

- ↩ Mohammed Hussein, “Mapping the World’s Oil and Gas Pipelines,” Al Jazeera, December 16, 2021.

- ↩ World Trade Organization, Trade Profiles 2021, 22, 70; “USA: World’s Largest Producer of Oil and Its Largest Consumer,” China Environment News, July 29, 2022, china-environment-news.net.

- ↩ Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III, The Limits to Growth (Washington, DC: Potomac Associates, 1972); Dennis Meadows interviewed by Juan Bordera, “Fifty Years After ‘The Limits to Growth,’” MR Online, July 21, 2022.

- ↩ See John-Andrew McNeish and Judith Shapiro, introduction to Our Extractive Age: Expressions of Violence and Resistance, ed. Shapiro and McNeish (London: Routledge, 2021), 3; Christopher W. Chagnon, Sophia E. Hagolani-Albov, and Saana Hokkanen, “Extractivism at Your Fingertips” in Our Extractive Age, 176–88; Christopher W. Chagnon et al., “From Extractivism to Global Extractivism: The Evolution of an Organizing Concept,” Journal of Peasant Studies 94, no. 4 (May 2022): 760–92.

- ↩ Alexander Dunlap and Jostein Jakobsen, The Violent Technologies of Extraction (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 34, 100, 120–21.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 4, 10.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1 (London: Penguin, 1976), 287; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 30 (New York: International Publishers, 1975), 145; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 35, 191. Gudynas attributed the popularization of the term “extractive industry” to international financial institutions such as the World Bank. He rejected the term as connoting that the extractive sector is part of industry and therefore productive. It is important to note that Marx employed the term as part of a sectoral analysis of production as a whole, and thus not separate from production. See Gudynas, Extractivisms, 3, 8.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (London: Penguin, 1981), 181–82.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 911.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 911; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 30, 62; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 46, 411.

- ↩ Joan Martínez-Alier, “Rafael Correa, Marx and Extractivism,” EJOLT, March 18, 2013. See also Eduardo Gudynas, “Would Marx Be an Extractivist?,” Post Development (Social Ecology of Latin America Center), March 31, 2013.

- ↩ See “Metabolic Rift: A Selected Bibliography,” MR Online, October 16, 2013; Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 638.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 20, 129. I am indebted to Ian Angus for drawing my attention to this passage.

- ↩ Marx used the term expropriation about thirty times in Part Eight of Capital on “So-Called Primitive Accumulation,” and he used “primitive accumulation”—which he repeatedly prefaced with “so-called” or placed within scare quotes, and used in passages dripping with irony—about ten times. He explicitly indicated in several places that the reality (and historical definition) of “so-called primitive accumulation” was expropriation, while the titles of the second and third chapters of this part both include “expropriation” or “expropriated.” See Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 871, 873–75, 939–40. For a general discussion of Marx’s concepts of appropriation/expropriation, see John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, The Robbery of Nature (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020), 35–63.

- ↩ On Polanyi, appropriation, and reciprocity, see Karl Polanyi, Primitive, Archaic and Modern Economies (Boston: Beacon, 1968), 88–93, 106–7, 149–56; Foster and Clark, The Robbery of Nature, 42–43.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 914–15.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 29, 461.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman, “Marx and the Indigenous,” Monthly Review 71, no. 9 (February 2020): 1–19.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 638; Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 182, 949.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 37, 733, emphasis added.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 638; Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 182, 949.

- ↩ Stephen G. Bunker, Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and the Failure of the Modern State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 22.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 26–27; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 28, 25; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 29, 461. On current Marxian work on expropriation, see Nancy Fraser, “Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode,” Critical Historical Studies (2016): 60; Nancy Fraser, “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography—From Exploitation to Expropriation,” Economic Geography 94, no. 1; Michael C. Dawson, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” Critical Historical Studies 3, no. 1 (2016): 149; Peter Linebaugh, Stop, Thief! (Oakland: PM Press, 2014), 73; Foster and Clark, The Robbery of Nature.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 4–7.

- ↩ Gudynas, “Would Marx Be an Extractivist?”

- ↩ Martin Arboleda, Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 2020). Generalized-monopoly capital is a term introduced by Samir Amin to designate twenty-first-century world political-economic conditions in which monopoly capital, with its headquarters for the most part in the imperial triad of the United States/Canada, Western Europe, and Japan, has spread its tentacles across the globe, including the globalization of production under its control. Late imperialism is a term indicating how these conditions have promoted new forms of the drain of surplus/value from the periphery to the core of the capitalist system. See Samir Amin, Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx’s Law of Value (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018), 162; John Bellamy Foster, “Late Imperialism,” Monthly Review 71, no. 3 (July–August 2019): 1–19.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 143–44.

- ↩ James Petras and Henry Veltmeyer, Extractive Imperialism in the Americas (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 20–48.

- ↩ Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1962), 22–43. In developing his notion of surplus and its relation to the environment, Gudynas declared that Marx’s theory of rent is helpful, “but even so the Marxist perspective is limited, particularly because it does not address environmental considerations.” His argument here runs into two problems. First, it failed to acknowledge the enormous advances in the understanding of Marx’s ecological critique in the last several decades, which have generated a vast literature globally. Second, in turning to Baran’s analysis of surplus to generate a political-economic and ecological critique of extractivism, Gudynas was drawing his inspiration from one of the leading Marxist economists of the twentieth century.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 83. On the relation of Baran’s concept of surplus to Marx’s concept of surplus value, see John Bellamy Foster, The Theory of Monopoly Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2014), 24–50.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 83–84.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 84–85. On how the concept of “natural capital” was converted from a use-value category in classical economics to an exchange-value category in neoclassical economics, see John Bellamy Foster, “Nature as a Mode of Accumulation,” Monthly Review 73, no. 10 (March 2022): 1–24.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 46, 411; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 30, 62; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 34, 391; Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 182, 949. Although Marx and Engels sometimes applied squandering to the destruction of the soil or human bodies, which were also seen as forms of robbery, the destruction of nonrenewable resources was characterized simply as squandering. On the corporeal rift, see Foster and Clark, The Robbery of Nature, 23–32.

- ↩ Baran, The Political Economy of Growth, 42.

- ↩ Gudynas, Extractivisms, 112–13.

- ↩ Clive Hamilton and Jacques Grinevald, “Was the Anthropocene Anticipated?,” Anthropocene Review 2, no. 1 (2015): 67.

- ↩ The notion of “accumulative society” is taken from Henri Lefebvre, The Critique of Everyday Life: The One-Volume Edition (London: Verso, 2014), 622.

- ↩ Carles Soriano, “On the Anthropocene Formalization and the Proposal by the Anthropocene Working Group,” Geologica Acta 18, no. 6 (2020): 1–10.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “The Capitalinian: The First Geological Age of the Anthropocene,” Monthly Review 73, no. 4 (September 2021): 1–16; John Bellamy Foster, “The Great Capitalist Climacteric,” Monthly Review 67, no. 6 (November 2015): 1–17.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 30, 40.

___________________________________________

Volume 75, Number 11 (April 2024)

John Bellamy Foster is a North American professor of sociology at the University of Oregon and editor of the Monthly Review. He writes about political economy of capitalism and economic crisis, ecology and ecological crisis, and Marxist theory.

John Bellamy Foster is a North American professor of sociology at the University of Oregon and editor of the Monthly Review. He writes about political economy of capitalism and economic crisis, ecology and ecological crisis, and Marxist theory.