Yusuf Islam’s Golden Years: Cat Stevens on Islam and His Return to Music

ARTS, 19 Jan 2015

The former Cat Stevens is still wrestling with his past – and winning.

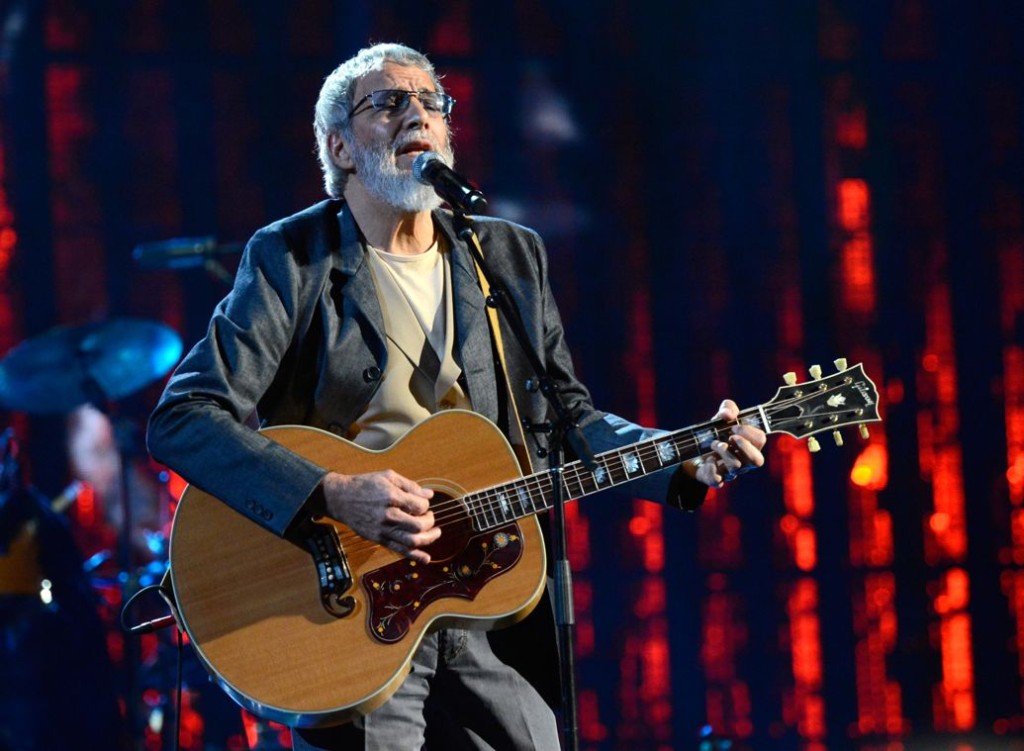

Yusuf Islam calls his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction “glorious,” adding “And Nirvana was explosive.” LEON NEAL/AFP/Getty Images

Nobody was expecting much from Yusuf Islam at the 2014 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony. The press had fixated on Nirvana’s reunion and the endless soap opera that is Kiss, mostly overlooking the fact that the former Cat Stevens was about to play his most prominent American gig since quitting music in 1978.

After a cheerful acceptance speech that avoided any mention of religion or politics, Yusuf took the stage with an acoustic guitar and delivered a stunning rendition of 1970’s “Father and Son” that silenced the rowdy crowd at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center. By the time a gospel choir joined Yusuf for a euphoric “Peace Train,” it seemed like the entire arena audience was on its feet, singing along to every word. “It was glorious,” says Yusuf. “It was great to sing without any barriers, and the choir really made the end very climactic. My son turned me on to Nirvana years ago, and their performance at the end was just explosive.”

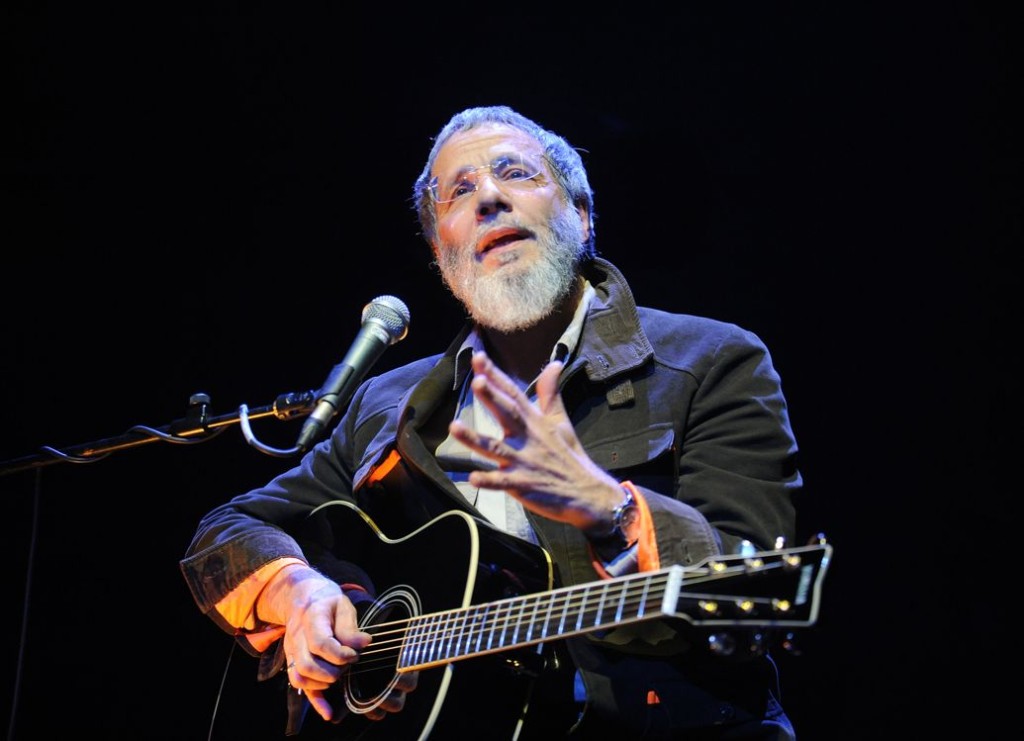

It’s now eight months later, and Yusuf, 66, is sipping tea in a conference room high atop the Sony Building in midtown Manhattan. His ever-present bodyguard, a beefy dude who stands at least six feet four, is perched on a nearby piano bench. Yusuf’s 29-year-old son, Yoriyos, is seated and gazing at a laptop. Yusuf’s salt-and-pepper hair is saltier than ever, and he’s wearing sunglasses, a gray peace train 2011 T-shirt and a stylish blue jacket. More than at any other point since his return to secular music eight years ago, he looks like a rock star.

Yusuf is relaxed and friendly, but everyone else seems a little on edge. His son anxiously looks up from his laptop when the conversation veers from music, and two publicists sit outside the door. Prior to the interview, they urged me to be “sensitive” when it comes to “religion and past controversies.”

The conversation starts on solid ground: Tell ‘Em I’m Gone, Yusuf’s R&B-flavored new LP, his third disc since 2006. Yusuf moved to Dubai in 2010 (“I like the sunshine”) but traveled to Los Angeles to cut the album with Rick Rubin. “We did the whole thing in a week,” Yusuf says. “A couple of songs were first takes. I don’t like hanging around studios. There was a couple of times where he wanted to go over bits again, and I said, ‘I’ve done it, Rick. I don’t want to do it again.’ ”

Yusuf recently wrapped his first North American tour since 1976. A show at New York’s Beacon Theatre was guaranteed to sell out, though he canceled it when he learned that New York outlawed paperless ticketing, causing tickets to sell for hugely inflated values on the resale market. “It just institutionalizes the scalping business, and that’s not fair,” Yusuf says.

The Beacon cancellation is just the latest bold, principled and (many feel) self-defeating move of Yusuf’s long career. He was born Steven Demetre Georgiou in London, the son of a Greek father and Swedish mother. Georgiou came of age just as his hometown was becoming the center of the rock universe. “I was very lucky,” he says. “I lived on the same street as the 100 Club, and [Beatles publisher] Dick James Music was four doors down from my father’s cafe. Everything was in this small radius in the West End of London.”

“I was never a supporter of the fatwa [against Rushdie], but people don’t want to hear that”

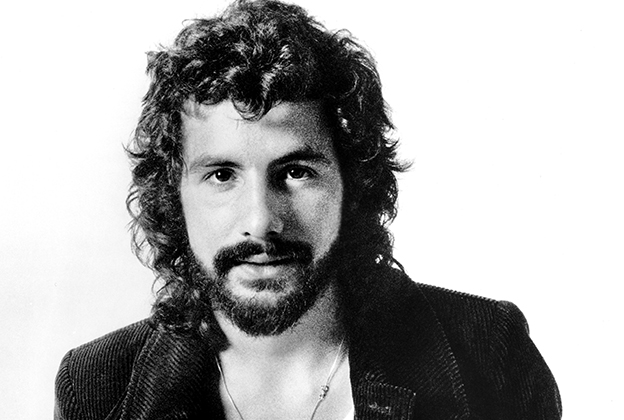

Hearing Bob Dylan for the first time changed his life. The 18-year-old Georgiou began playing London coffeehouses under the name Cat Stevens and penning future classics like “The First Cut Is the Deepest.” A case of tuberculosis in 1968 nearly killed him, but his career exploded in 1970 when “Father and Son” and “Wild World” hit radio. It was the era of the sensitive singer-songwriter, and Stevens fit right in on the airwaves next to James Taylor and Carly Simon.

Even when he became a superstar, Stevens had a hard time enjoying himself – tuberculosis helped see to that. “TB is a very bluesy kind of illness,” he says. “I did LSD a few times, but I stayed away from the rock-star life because I was so worried about my health. I became a vegetarian, and I carried around a suitcase full of vitamins and special drinks everywhere I went.”

Everything changed one day in 1976, when Stevens went for a swim in the ocean near Malibu. As he tried to swim back to shore, he realized the current was too strong to fight, and after struggling for a time he found himself on the verge of drowning. “I didn’t have any strength left,” says Yusuf. “There was only one place to go, and that was God. I never doubted God’s existence, but I never called on him because everything had seemed all right in my life. This was life-and-death.”

He pledged his complete and utter allegiance to God if he’d save him, and suddenly a wave pushed him to shore. Not long afterward, his brother David gave him a copy of the Quran. “This was before Islam was a headline,” Yusuf says. “The Iranian Revolution wasn’t even on the horizon. I felt like I was discovering something that was an amazing and immense secret.”

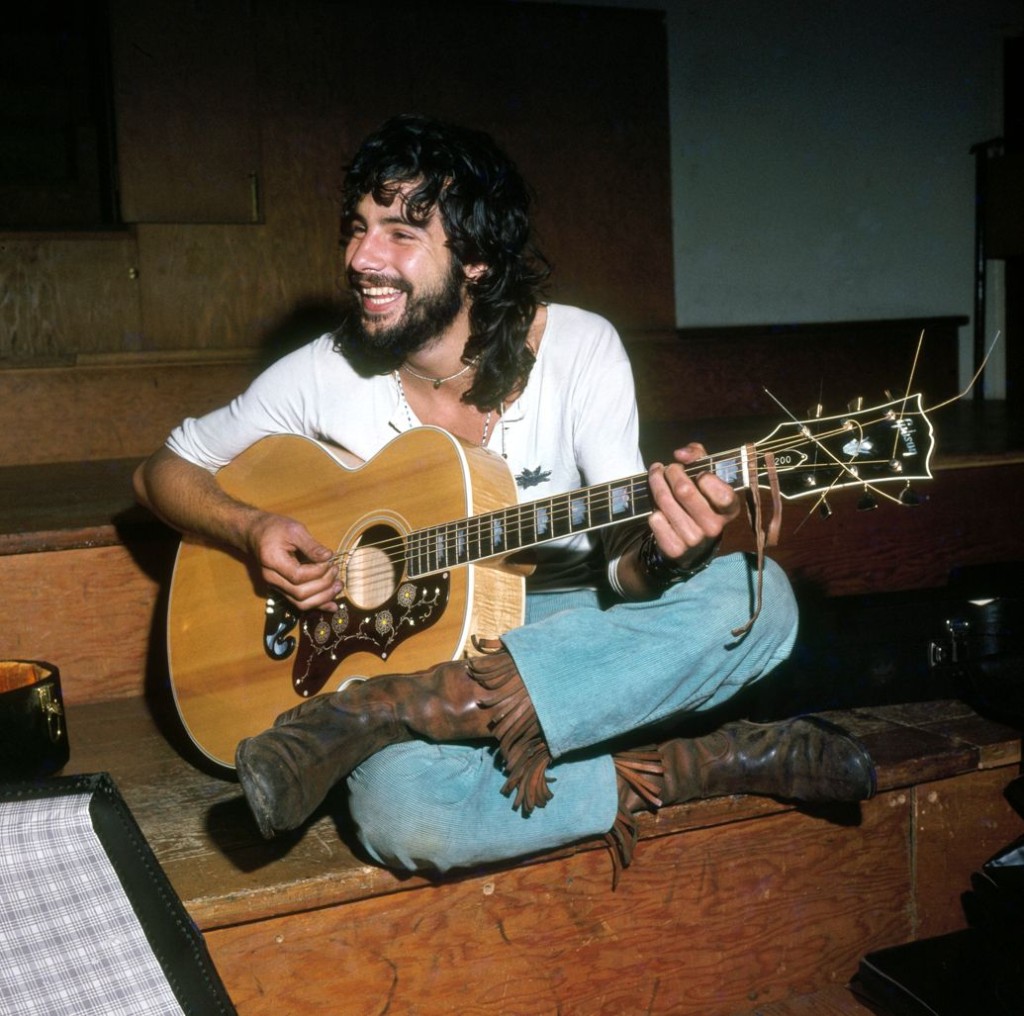

Within two years, Cat Stevens had become Yusuf Islam. He devoted himself to Allah, deciding all forms of music were against the faith. He walked away from a record contract and sold all of his guitars. His sole income came from publishing, but he gave away royalties from any song he declared anti-God: “Anything that encouraged love without marriage or was too specific in the sexual region went.” It amounted to about 40 percent of his catalog. “Take ‘The Boy With a Moon and Star on His Head.’ You might think it’s OK, but the guy makes love to a farmer’s daughter on the way to his wedding. So, no. . . .”

Yusuf lost touch with the music world. “I vaguely knew things like Madonna, MTV and Michael Jackson were happening, but I was not interested at all,” he says. “As far as I was concerned, the last great record was Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life.” Yusuf focused on his growing family, a series of Muslim schools he founded across England, and Small Kindness, a charity he put together to assist the victims of war and famine in the Third World.

Over the years, Yusuf’s children tried in vain to get him to begin playing guitar again. Then, a few months after 9/11, Yusuf found himself holding an acoustic guitar his son had brought home. It was late at night, and his family was asleep. “I just thought, ‘Let’s have a go and try,’ ” he says. “I looked for F, and I found it. I don’t remember what songs I played, but when it was done I began crying.”

Yusuf was conflicted about playing again, but the war in Afghanistan was raging and another conflict was looming in Iraq. Yusuf says that the world needed to see at least one nonviolent Muslim on TV. “There was so much antagonism in the world,” he says. “Many Muslims have come up to me, shook my hand and said, ‘Thank you! Thank you.’ I’m representing the way they want to be seen. So much of the middle ground gets forgotten in the extremities we witness around the world.”

Yusuf quietly began gigging around Europe and played a couple of tiny showcases in America. He didn’t face a big crowd until Jon Stewart invited him to appear at 2010’s Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear. Yusuf was taking part in a hilarious bit – he performed “Peace Train” while Ozzy Osbourne performed “Crazy Train” – but it also reignited a controversy that’s been haunting Yusuf for a quarter-century.

After the Ayatollah Khomeini declared a fatwa against author Salman Rushdie in 1989, Yusuf had told a crowd at London’s Kingston University that “[Rushdie] must be killed. The Quran makes it clear: If someone defames the prophet, then he must die.” Yusuf later partially walked the comments back, but the issue refused to die. When Rushdie heard about Yusuf goofing around with Osbourne, he phoned Stewart in a huff. “It became very clear to me that [Yusuf] is straddling two worlds in a very difficult way,” Stewart said two years ago. “I wouldn’t have done [the bit], I don’t think, if I had known that. . . . Death for free speech is a deal-breaker.”

It’s still a sensitive subject for Yusuf. When I broach it, his son looks up, concerned. “People need to get over it,” says a clearly irritated Yusuf. “It’s 25 years ago. I’ve got gray hair now. Come on. I was fool enough to try and be honest and tell people my position. As far as I’m concerned, this shouldn’t be the subject of my life.”

That appears to be the end of it, and Yoriyos looks relieved. But Yusuf can’t help himself. “I’m a firm believer in the law,” he says. “I was never a supporter of the fatwa [against Rushdie], but people don’t want to hear that because they keep saying that I believe in the law of blasphemy. All I’m saying is, how can you deny the Third Commandment? It’s an Islamic principle that you must follow the law of the land where you reside.”

Unapologetic answers like that are what make Rushdie and his many supporters unable to forgive Yusuf, and he knows their feud will never end. “That’s the way life is,” he says. “I don’t want to put myself in this bracket, but if you look at any messenger, there’s going to be an antagonist.”

One song on Yusuf’s new album seems to take aim at the controversy: “Cat and the Dog Trap.” “Cat’s in a cage,” he sings. “Chained to a stone/Empty bowl by his side.” Yusuf admits the song is autobiographical, but he refuses to ID the inspiration behind the antagonistic dog, though Rushdie is a likely suspect. “I used to be followed by a moon shadow,” Yusuf says when pushed on the topic. “Now I’m followed by all these misconceptions, and they’re like a ball and chain. I just want to write music from my heart and give people a message of hope and the search for a better place.”

The ISIS threat has brought America to the verge of yet another war in Iraq, but it has made Yusuf oddly optimistic: “The positive side is that it has brought together these factional voices to say in unison that [ISIS] has nothing to do with Islam. Muslims have been subjected to so many tyrants and oppressive regimes. That’s what the Arab Spring was about, but the problem comes in trying to direct a revolution.”

Tickets for Yusuf’s upcoming American shows read “Yusuf/Cat Stevens” – a concession to fans of his classic albums, and the move of a man who has grown increasingly comfortable with his past. “When you’ve been running for so long, you might realize you’ve run too far,” he says. “There comes a time to say, ‘Hang on. I’ve lost my way a little bit.’ ”

Go to Original – rollingstone.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.