Spies Hacked Computers Thanks to Sweeping Secret Warrants, Aggressively Stretching U.K. Law

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE, 29 Jun 2015

Andrew Fishman and Glenn Greenwald – The Intercept

22 Jun 2015 – British spies have received government permission to intensively study software programs for ways to infiltrate and take control of computers. The GCHQ spy agency was vulnerable to legal action for the hacking efforts, known as “reverse engineering,” since such activity could have violated copyright law. But GCHQ sought and obtained a legally questionable warrant from the Foreign Secretary in an attempt to immunize itself from legal liability.

GCHQ’s reverse engineering targeted a wide range of popular software products for compromise, including online bulletin board systems, commercial encryption software and anti-virus programs. Reverse engineering “is essential in order to be able to exploit such software and prevent detection of our activities,” the electronic spy agency said in a warrant renewal application.

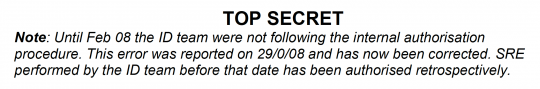

But GCHQ’s hacking and evasion goals appear to have led it onto dubious legal ground and, at times, into outright non-compliance with its own procedures for staying within the bounds of the law. A top-secret document states that a GCHQ team lapsed in following the agency’s authorization protocol for some continuous period of time. Meanwhile, GCHQ obtained a warrant for reverse engineering under a section of British intelligence law that does not explicitly authorize — and had apparently never been used to authorize — the sort of copyright infringement GCHQ believed was necessary to conduct such activity.

The spy agency instead relied on the Intelligence Services Commissioner to let it use a law pertaining only to property and “wireless telegraphy,” a law that had never been applied to intellectual property, according to GCHQ’s own warrant renewal application. Eric King, deputy director of U.K. surveillance watchdog Privacy International said, after being shown documents related to the warrant, “The secret reinterpretation of powers, in entirely novel ways, that have not been tested in adversarial court processes, is everything that is wrong with how GCHQ is using their legal powers.”

GCHQ may have also circumvented a restriction on using the type of warrant it obtained for domestic purposes; the agency said in one memo that it has used reverse engineering to support “police operations” and the domestic policing-focused National Technical Assistance Centre.

The agency also described efforts to cozy up to dozens of government staffers it believed could help obtain further warrants.

The agency’s slippery legal maneuvers to enable computer hacking call into question U.K. government assurances about mass surveillance. To assuage public concern over such activity, the government frequently says spies are subject to rigorous oversight, including an obligation to obtain warrants. As it turns out, such authorizations have, at times, been vague and routine, as demonstrated by top-secret memos prepared by GCHQ in connection with the reverse engineering warrant.

The controversial path GCHQ took to authorize reverse engineering also seems likely to lend momentum to an ongoing push to reform the way surveillance warrants are issued in the U.K. Earlier this month, the U.K.’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, David Anderson, issued a report recommending that “all warrants should be judicially authorised” and describing the current regulatory system as “undemocratic, unnecessary and — in the long run — intolerable.”

This story is based on 22 documents from NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, linked below. None have been published before. One was briefly described in a January story in The Guardian.

Widely used commercial software is targeted

One document describing the warrant, a 2008 warrant renewal application, identifies numerous commercially available products in which GCHQ identified vulnerabilities through reverse engineering. These include widely used encryption software such as Exlade’s CrypticDisk and Acer’s eDataSecurity. Exlade’s products are used by “thousands of companies and government agencies,” including tech giants IBM, Intel, GE, HP and Seagate, according to the company’s website. Also successfully targeted were popular web forum services vBulletin and Invision Power Board. VBulletin says its users include Sony Pictures, NASA, Electronic Arts and Zynga. Invision Power Services, the maker of Invision Power Board, said around the time of the warrant renewal application that its users included Yahoo, AMD and Sony. GCHQ also targeted CPanel, software used by large hosting companies like GoDaddy for configuring servers, and PostfixAdmin, used to manage Postfix, popular email server software.

Invision Power Services said in a written statement that it monitors its software and external sources closely for information on vulnerabilities and issues fixes quickly. “There are currently no open vulnerabilities in our software of which we are aware,” it added. vBulletin and Acer did not provide comment by press time. The maker of CPanel did not respond to a request for comment.

Particularly important to GCHQ was the ability to hack anti-virus programs, an offensive operation that would typically come after using reverse engineering to discover vulnerabilities. Interfering with such programs would allow the opportunity to breach a computer’s defenses in order to exploit the computer without detection. GCHQ cited as a particular target Kaspersky Labs, a prominent Moscow-based maker of anti-virus software that claims more than 270,000 corporate clients. (For details on the targeting of Kaspersky, see this accompanying piece by Andrew Fishman and Morgan Marquis-Boire.)

“Personal security products such as the Russian anti-virus software Kaspersky continue to pose a challenge to GCHQ’s CNE [computer network exploitation] capability and SRE [software reverse engineering] is essential in order to be able to exploit such software and to prevent detection of our activities,” the 2008 document says.

Also targeted by the agency’s warrants are hardware products such as large computer network routers, critical pieces of infrastructure. Hacking Cisco routers “has been good business for us and our 5-eyes partners for some time now,” boasts a 2012 NSA document previously published by The Intercept.

The warrant memo describes GCHQ’s “capability against Cisco routers,” specifically that “GCHQ’s [hacking] operations against in-country communications switches (routers) have also benefited from SRE.” That has enabled the agency not only to access “almost any user of the internet” inside the entire country of Pakistan — but also “to re-route selective traffic across international links toward GCHQ’s passive collection systems.” The Guardian previously described, but did not publish, this memo.

Cisco did not comment specifically on the warrant document, saying in a written statement only that its products are securely developed and tested, that the company has a “robust” process for handling vulnerabilities, and that “Cisco does not work with any government, including the U.K. Government, to weaken or compromise our products.”

Stretching the law

To support its efforts to probe and compromise software systems, GCHQ appears to have aggressively stretched Britain’s Intelligence Services Act, failed to comply with its own guidelines based on that law for a continuous period, and even intentionally cozied up to staff in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, or FCO, to get warrants approved. The apparent success of these efforts highlights the illusory nature of surveillance oversight, despite repeated government statements that the U.K. spy machine is tightly controlled.

GCHQ needed warrants, according the documents, to protect itself from potential claims of copyright infringement or of breaching a licensing agreement. The practice of reverse engineering is frequently barred in the terms and conditions attached to the copying and use of particular software by the makers of that software.

“In 2008, there was no real authority on this issue in the EU or the U.K.,” says Indra Bhattacharya, a U.K. solicitor with the firm Jones Day who specializes in intellectual property law. A 2012 EU court ruling and a related 2013 U.K. court ruling allow greater latitude toward specific reverse engineering practices as long as there is no copying of code, he explains, but case law is “very fact-specific” and “deals mostly with commercial situations,” making it difficult to determine how it might apply to a government agency and whether it would obviate the need for GCHQ’s warrant.

But at the time of the warrant renewal application, GCHQ was clear on its legal position. “Reverse engineering of commercial products needs to be warranted in order to be lawful,” one agency memo states. “There is a risk that in the unlikely event of a challenge by the copyright owner or licensor, the courts would, in the absence of a legal authorisation, hold that such activity was unlawful.” Even if warrants shielded GCHQ from domestic law, the agency believed the warrant would not protect it under international law, noting that such warrant-based immunity would be “limited,” given that “it only covers us under U.K. law.”

GCHQ obtained its warrant under section 5 of the 1994 Intelligence Services Act, which covers interference with property and “wireless telegraphy” by the Security Service (MI5), Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and GCHQ. Section 5 of the ISA does not mention interference in intellectual property, which the intelligence agency believed was necessary to reverse engineer software, but a top-secret memo states that the intelligence services commissioner approved such use in 2005.

This stretching of the law was dubious, says King, of Privacy International.

“It is not the Commissioner’s function to provide the authoritative interpretation of any law,” King says.

GCHQ did not need to go to an independent court or focus the scope of the warrant on a specific target to obtain the reverse engineering authorization. The warrant, like many surveillance warrants in the U.K., was granted by a cabinet minister, a practice harshly criticized in a just-issued report by the U.K.’s “terrorism watchdog.”

The warrant renewal request for reverse engineering published today was addressed to the official that oversees GCHQ, the foreign secretary, then David Miliband, as well as two other FCO officials. The warrant is subject to renewal twice a year.

Cozying up to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office

While it was trying to hack software, GCHQ actually had efforts targeting FCO as well. Documents reveal the spy agency made a concerted effort to build personal relationships with key FCO staff with the goal of getting GCHQ warrants approved. One GCHQ document marked “Restricted” stated, under the heading “FCO,” that “top five objectives in 08-09” included moves to provide a “greater level of routine contact between GCHQ and FCO seniors, and map members of FCO SLF [Senior Leadership Forum] to their SI/IA [Signals Intelligence/Information Assurance] interests.” Another objective was to “ensure that GCHQ and FCO warrantry and submission procedures are fit for purpose given increasing complexity and need for pace in our work.”

Then followed a list of dozens of named FCO staff members and a corresponding list of “major issues and targets for 09-10” for each, with goals like “win confidence by following his diary and briefing at key times,” “build strong relationship with successor,” “Positive about intelligence, build relationship,” “Colin is new — Build relationship,” and “Generally supportive of submissions but could be more so.”

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2107835-fco-relationships-amp-goals-08-09-gchq.html

Oversight issues

For all its efforts to win aggressive warrants clearing its reverse engineering as legal, GCHQ may well have failed to stay even with the broad boundaries it was given. When Snowden first came forward, he said part of his motivation was that there was so little monitoring of the searches NSA analysts could conduct, ensuring that abuse would often go undetected. GCHQ documents indicate there are similar problems of oversight at the British agency.

One agency memo about the reverse engineering warrants notes that, for a length of time that can’t be ascertained from the document, internal authorization procedures were not adhered to by the Intrusion Detection team. When the error was discovered, the actions were simply retroactively approved.

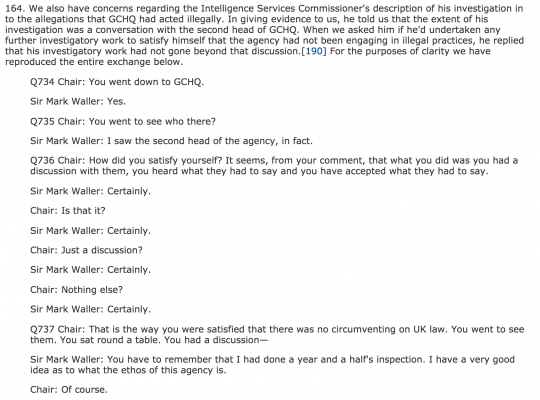

Previously published news accounts have shown that the intelligence services commissioner works only part-time, and as of last year, had a staff of one. It was the ISC who approved the stretching of the Intelligence Services Act section 5 for use in GCHQ’s software reverse engineering warrant. The ISC is also responsible for “independent external oversight” of the intelligence community. The current ISC, Sir Mark Waller, told the House of Commons’ Home Affairs Committee that in 2012 he saw approximately 6 percent of more than 2,800 total warrants, with the percentage rising to roughly 12 percent the following year.

In a detailed and scathing 2014 report, the committee challenged the rigor of the ISC’s oversight, citing as evidence Waller’s own words:

The committee’s report concluded, in boldface type: “We do not believe the current system of oversight is effective and we have concerns that the weak nature of that system has an impact upon the credibility of the agencies accountability, and to the credibility of Parliament itself.”

Did GCHQ improperly use the warrant to “enable police operations?”

GCHQ may have improperly used the reverse engineering warrant for certain police-related activities, judging from language in the renewal document.

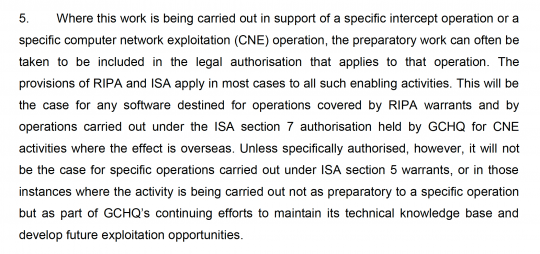

The reverse engineering warrant appears to have been used by GCHQ to support domestic law enforcement agencies and also appears to mirror existing authorizations for “activities where the effect is overseas,” as one GCHQ memo put it.

The GCHQ warrant renewal application states that a number of the software exploitation efforts conducted “under the terms of this warrant … enable police operations.”

The application also indicates that the warrant was used to subvert software on behalf of the National Technical Assistance Centre, or NTAC. NTAC is much more focused on domestic and law enforcement matters than on GCHQ’s wider intelligence and security mission. The application says that GCHQ, on behalf of NTAC, reverse engineered Acer eDataSecurity encryption and unlocked “material relating to a high profile police case.” It says it similarly thwarted CrypticDisk for NTAC, “allowing for the decryption of material relating to a child abuse investigation.”

The GCHQ memo on the warrant renewal states:

The full extent of how GCHQ has applied the section 5 warrant authority to “enable police operations” is unknown. But the limitations of ISA are clear: GCHQ and MI6 cannot directly use a section 5 warrant to interfere with “property in the British Islands” if their function is “in support of the prevention or detection of serious crime,” which falls under the purview of traditional law enforcement. “GCHQ should not be obtaining section 5 warrants if the purpose of the warrant is to prevent serious crime domestically,” says King. The citation of police cases right in the application to justify renewal of the warrant would seem to make it difficult for GCHQ to argue that use by the police is incidental.

GCHQ refused to comment on the record about any of these matters, instead providing its boilerplate response about how it complies with the law.

___________________________

Documents published with this article:

- GCHQ Application for Renewal of Warrant GPW/1160

- U.K. Ministry Stakeholder Relationships Spreadsheets (13 documents merged)

- Software Reverse Engineering

- Reverse Engineering — Wiki

- Malware Analysis & Reverse Engineering – ACNO Skill Levels

- TECA Product Centre — Wiki

- Intrusion Analysis

- TSI — Legal Authorisation Flowcharts: Targeting & Collection (2 documents merged)

- Operational Legalities – Powerpoint Presentation

Email the authors: fishman@theintercept.com, glenn.greenwald@theintercept.com

Go to Original – firstlook.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE: