Dubai’s Skyline Is a Monument to Oppression, Not Prosperity

MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA, 10 Aug 2015

Laith Shakir – Foreign Policy In Focus

Visual artist Arko Datto combines satellite images and text to paint a picture of migrant workers’ lives in the Arabian Peninsula — and his findings aren’t pretty.

Over the past few decades, the booming oil economy and real estate market in the United Arab Emirates have earned the nation a reputation for opulent wealth. From towering skyscrapers, man-made islands, and indoor ski-slopes to sprawling highways and bridges, the UAE — and Dubai especially — has become synonymous with resplendent metropolitanism.

At first glance, Dubai’s rapid urban development seems to be nothing short of a modern engineering miracle. Viral images depict a massive city rising from the desert over just 20 years, a virtually unprecedented amount of growth in such a short period of time. This development has been praised as the world’s fastest, and the buildings themselves have been lauded for their “sophistication” and “authenticity.”

Dubai’s astonishing growth is generally credited with transforming the entire UAE for the better. Beneath Dubai’s veneer of progress, however, something is very, very wrong.

The city’s glitzy buildings and highways — traditionally seen as monuments to the entire region’s economic success — are testaments to the work done by migrant workers from Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

Human Rights Watch estimates that over 5 million low-paid migrant workers currently reside in the United Arab Emirates alone, a population far exceeding the country’s nationals and largely responsible for shaping the region into the economic and architectural juggernaut it is today. Yet these workers are all but invisible in the cities they built. Stowed away in ramshackle compounds and forced to work long hours in oppressive heat, they’re deliberately kept away from the public eye.

Juxtaposition

Arko Datto, a visual artist currently based in India, is well aware of this fact. While traveling, he recalls being “fascinated with the bustling megalopolises of Arabia, a cold post-apocalyptic vision of towering megaliths seen across the hazy abrasive heat.”

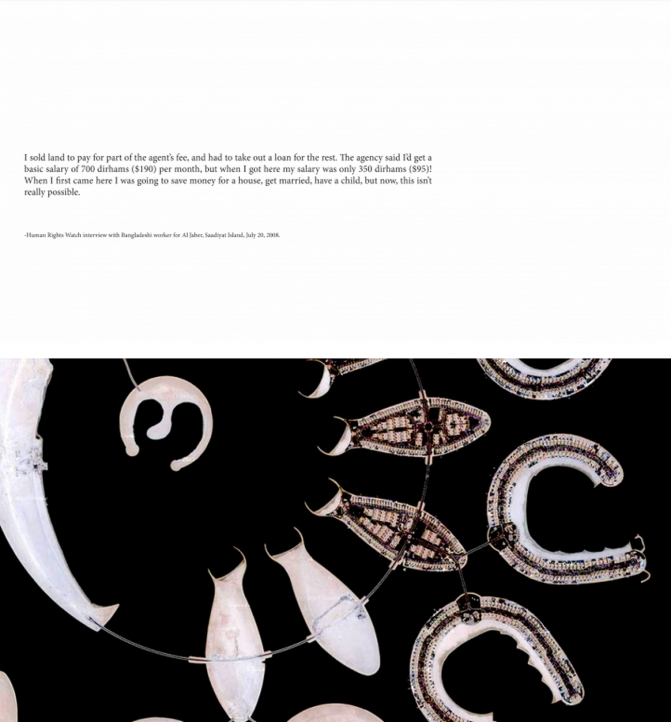

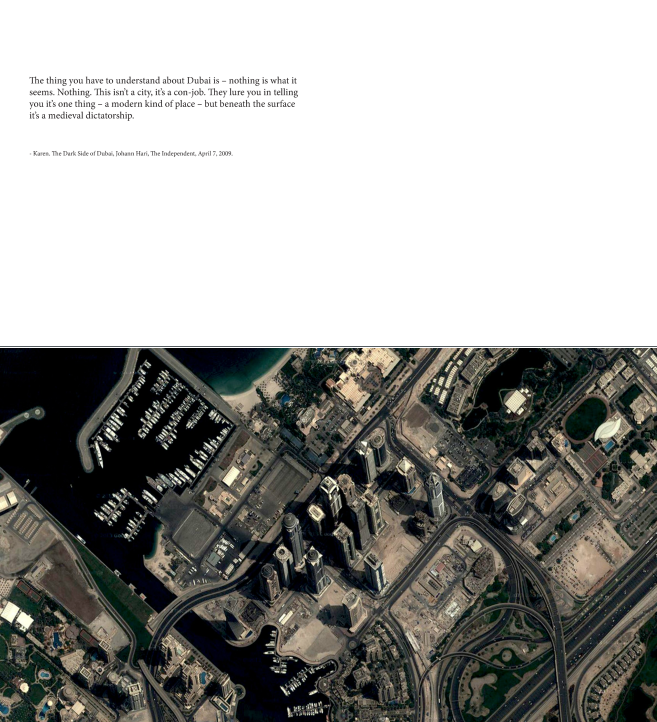

This interest, combined with recent developments in satellite imaging technology, culminated in Crossings: Promenades in the Arabian Desert — an art project combining Google Earth and Maps images with quotations about the reality of migrant workers in the region, derived from firsthand accounts and fact-finding reports.

According to Datto, the project shows “the society that the migrant diaspora has helped construct, shape, and maintain while occupying the bottom echelons of society.” In Crossings, he weaves a story detailing the plight of migrant workers, creating a narrative of their experiences in both the UAE and the Arabian Peninsula as a whole.

The media has already uncovered Qatar’s deplorable worker’s rights track record, amidst FIFA’s decision to grant the country’s bid to host the 2022 World Cup. The Guardian reports that Nepalese migrant workers died at a rate of one every two days in 2014 — a figure that excludes workers from other ethnic backgrounds, which would drive the number up significantly.

This international scrutiny has yet to shift to other rights offenders in the region, a glaring omission that Datto is helping to remedy.

In the Shadow of Glitz

Throughout the digital book, stunning satellite images of architectural landmarks are juxtaposed with interviews from migrant workers, Emirati foremen, and Western expatriates, along with excerpts from legal and human rights briefs. Together, these divergent sources help paint a picture of daily life for migrant workers — and it’s far from a pretty one.

These individuals are lured to the UAE with promises of high wages and easy living — conditions that are vast improvements from their previous lives.

Sahinal Monir, a 24-year-old from Bangladesh, described his recruitment story to the Independent. An employment agent arrived in his village, advertising monthly wages of £400 for a 9-to-5 construction job. Monir was promised “great accommodation, great food, and fair treatment.” He only had to take out a £2,300 loan for a work visa — and that could be paid off, he was told, in “the first six months, easy.”

It sounded too good to be true. And it was.

As soon as Monir arrived in Dubai, the construction company immediately confiscated his passport. The company then told him that he would be working 14-hour days in the desert heat — where, as The Independent reports, tourists are “advised not to stay outside for even five minutes in summer” — for less than a quarter of the wages he’d been promised.

When Monir protested, the company told him to go home if the conditions weren’t satisfactory. “But how can I go home? You have my passport, and I have no money for the ticket,” he said. “Well, then you’d better get to work,” they replied.

Monir’s living quarters embody the lie he was sold. He lives in a “tiny, poky, concrete cell with triple-decker bunk-beds,” which he shares with 11 other men. The lavatories in the camp — little more than glorified ditches — are “backed up with excrement and clouds of black flies,” filling the entire facility with an unbearable stench. Monir has no access to air conditioning or fans, so the heat is “unbearable. You cannot sleep. All you do is sweat and scratch all night.”

At the Crossroads

Monir’s story is one of many detailed in Crossings, highlighting the systemic abuse faced by migrant workers. The juxtaposition of sprawling highways, gargantuan skyscrapers, and decadent artificial islands with these stories highlights the slavery-like conditions that made these monuments possible.

In the context of the workers’ stories, Dubai’s architectural wonders shift from testaments to the city’s cosmopolitanism to stark reminders of its reliance on systemic exploitation.

Despite protests and increased scrutiny, migrant workers’ conditions in the UAE have yet to improve significantly. Though Crossings elicits a sense of despair and hopelessness in the audience, the project is helping to bring these issues to a wider audience. “I want to show to the world a bitter truth that is at the crossroads of capitalism and racism,” Datto told Wired.

Crossings undermines the carefully constructed “silence” maintained by the Emirati elite, delivering a clear and unavoidable message about the deplorable conditions of over 5 million migrant workers in the UAE. Only time will tell if the international community chooses to listen.

Crossings: Promenades in the Arabian Desert is available for free at arkodatto.com/crossing.

_______________________________________

Laith Shakir is a fellow of the Next Leaders program at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA: