Mansions and Slums: The Inequality of Living Space

IN FOCUS, 7 Nov 2016

3 Nov 2016 – Australians have the biggest homes in the world. New free-standing homes are an average 245.3 sqm – three times bigger than UK homes, and 22 times bigger than the average Hong Kong home.

For Australia, this space privilege shows up the all pervasive myth that the country has no room for refugees. But for the world, there’s a deeper story of a global inequality of space – a story that goes well beyond mere population density differences.

Inequality of space

With 7 billion people in the world, how much space did each person get?

Thousands got mansion amounts of space and hundreds of rooms each. US heir (his only occupation) William Amherst Vanderbilt Cecil’s mansion had a banquet hall alone that was double the size of the average first world house.

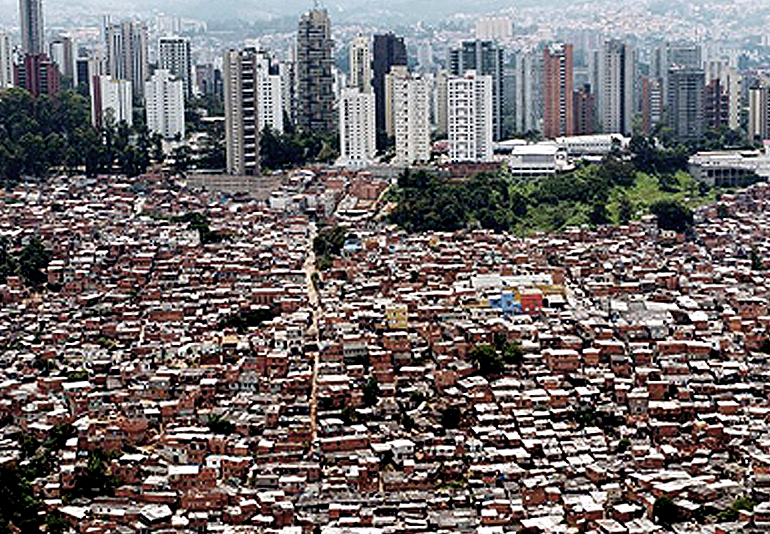

1 billion people got slum-space – barely enough for the family to huddlesleep on one improvised mattress. The corrugated iron walls of their cupboard homes built on the edge of mountains and on the edge of cities and the edge of life, let the arguments in.

9 million people got prison space, and understood that the closer walls are, the more arguments there are.

65 million refugees got tent space or prisons, as they waited years for help. Photos weren’t hung up, because this wasn’t home yet, this was limbolife.

And over 100 million people got shop steps of space, their dragon hearts mistaken for street stains and their sleep adjusted to the shape of stairs and to office opening hours. Cardboard softened the ground.

The housing hierarchy

The unequal distribution of living space is part of the fabricated global hierarchy of human value. Living space, in a similar way to work space, or space on public transport, subtly communicates that some people are worth more, and have more power. Offices around the world play the desk game, where the boss has the big desk and the large office, supervisors have medium sized desks, and the rest share a desk with an assembly line of other workers. On buses, men will often spread their legs out, leaving women quietly squished on their half of the seat. Likewise, the world’s mansion owners don’t actually need the two pools and the 40 car spaces. Like immature territorial animals, these space-stealers are making big statements about their small selves – about their worth and power.

For the mainstream media, poor people’s lives and third world lives matter less. The less you own, the less space you take up, the less heart strings your home, broken in an earthquake, will pull.

The average floor space per person is less than 20 sqm in all African countries covered by a UN study. Meanwhile, France has an average 43 sqm per person, Canada 72, Japan 35, UK 33, Germany 55, US 77, and Australia 89.

How much space does each person need for dignity and privacy?

And while the need for one’s own space and for privacy may have cultural variations, it is also deeply human. Virginia Woolf said that every woman needs a room of her own if she is to write. Women, often spending the whole day attending to others’ needs (through work, family, or partners) tend to lack space where they can process the day, think, and dream. Likewise, a lot of poor people don’t have the space or time to dwell and dream.

A crampled home is often a reflection of a narrow world: with poverty limiting how far people can travel, what work they can aspire to, who they meet, and what they experience. Many people see their home and their rooms as part of expressing their identity. But slums and other kinds of crowded housing can be repetitive, dysfunctional, and depersonalising. Dense urban living is often paired with apathy, and indifference. And people who live in informal housing tend to be excluded from society, while even people who rent are often excluded from communities as those who have permanent housing see them as temporary, passing, and less invested. On the other hand, when people have secure land tenure and housing, they are more likely to invest in their communities.

Homes are meant to be safe places, but research has found that crowding-related stress can increase domestic violence, and substance abuse, and overcrowding is often associated with greater competition for work. Children in crowded apartments and low-income housing can end up being withdrawn and have trouble concentrating, according to The Atlantic.

Meanwhile, unnecessarily large homes, beyond the status and value they dote on their owners, also encourage consumerism – becoming giant storage warehouses for useless, expensive items.

Ultimately, the exact amount of space people need varies according to cultural and personal preferences and individual situations. But there is a line, with the majority of the world living below it.

India

In India, the average living space per person is 6 sqm. A third of the population have less space than US prisoners, according to a national survey. In this complex country of study, struggle, hope, failing infrastructure, crowded trains, and dusty Delhi streets, alcohol is often cheaper than food, and many cities in India have just one hour of water a day, with not a single city completely sewered, despite the searing summer heat.

Sometimes, five to six people live in one room – and in that small room, people sleep, cook, wash, and play. In the slums, mental health issues tend to be sidelined by physical health issues. But people in such situations deal with a higher proportion of mental disorders, as they sleep sitting up due to overcrowding, and face rats and food insecurity.

In the Kaula Bandar slum, adults often sleep outside, women sleep while children are at school and men often take night shift work so others have space to sleep. Aggressive policing and demolitions stop people expanding their homes. People rarely invite guests over to visit, and when they do, the adults go outside, or guests stay in nearby communal religious spaces. Families eat food in shifts, and when an adult is sick, children sleep in a neighbour’s home.

White wall face

Their home was one room, and the bed was a desk and the cupboard was for cooking and clothes. Rain flavoured breakfast eaten on the edge of the bed, a gas sooted sink, paint covering up old walls, plasticbag bin that always slipped with a crashspill off the sink drawer, paint in her throat and a white powdered cough for weeks. No place to pace.

Gashes in the concrete because this whole city was crumbling super slowly and all the people with it, year by year. They rearranged things to stop the walls shrinking and create space, like magic, but the narrow walls continued to steal their ideas and dreamings, leaving them with blank eyes.

Where does housing inequality come from?

Perhaps with the exception of the UK, countries with higher average housing sizes tend to be those countries that have benefited from invading countries that are hence now poor, or from directly stealing their natural resources. On a more local scale, building dignified housing for the poor, especially in cities, isn’t profitable, and so it doesn’t happen. Poor people receiving exploitative wages struggle with paying rent, or end up in informal housing. Meanwhile, the mansion dwellers play games with housing – their speculation bringing up prices and seeing many homes left empty for years.

_______________________________________

Tamara Pearson is a long time journalist based in Latin America, and author of The Butterfly Prison.

Go to Original – counterpunch.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.