At Walden, Thoreau Wasn’t Really Alone with Nature

IN FOCUS, 17 Jul 2017

John Kaag and Clancy Martin – The New York Times

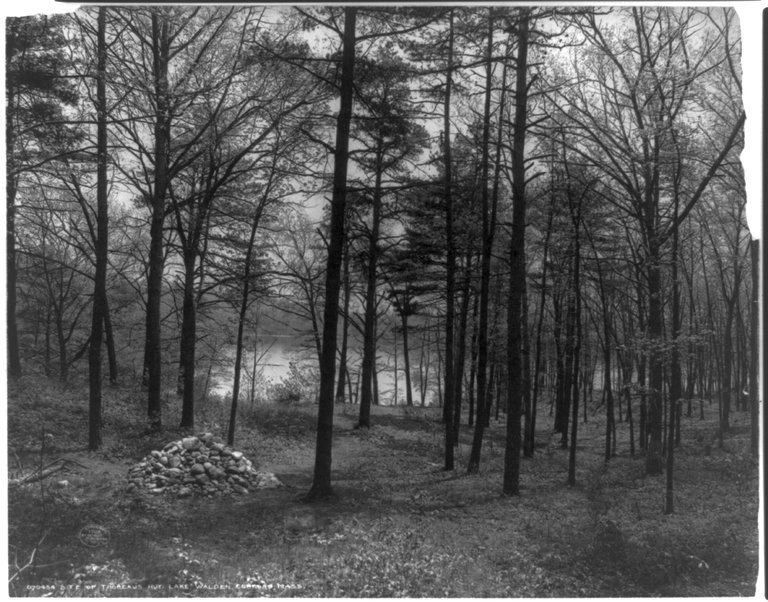

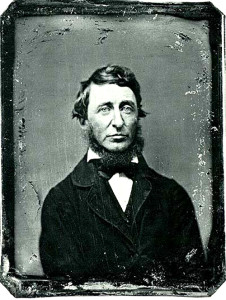

10 Jul 2017 – He lived on an acre just above Walden Pond. He had a small garden, survived off the land, and enjoyed the wild apples that still grew around Concord, Mass., in the 19th century. He stayed near Walden because it was here that he could be most free.

His name was not Henry David Thoreau.

Brister Freeman was a black man, one of the original inhabitants of Walden Woods. As Laura Walls tells us in her new biography of Thoreau, Freeman fought in the Revolution, and afterward “declared his independence through his surname,” but “unable to prove his freedom outside of Concord, he bought an acre on the hill north of Walden Pond, Brister’s Hill.” Today, Walden is preserved as a national park, and, so long as they can find parking, people come and go as they please — as did Thoreau — but many of his neighbors couldn’t.

On Thoreau’s 200th birthday this July he might want us to remember the men and women, largely unacknowledged by history, who were confined to this paradisiacal corner of the earth. It was, indeed, a sanctuary, but for many of Thoreau’s companions freedom was narrowly circumscribed. Their world was, according to the historian Elise Lemire, the “Black Walden,” a place of not-so-quiet desperation.

For consumers of conventional history, it is easy enough to fall into the impression that Thoreau was the only person at Walden, that the pond was a pristine tract of wilderness. It wasn’t. Walden was just beyond the bounds of civilized convention — which meant that it was a place for outcasts. Thoreau knew this, and willingly lived among them, those who had been barred from the inner life of many wealthy suburbs of Boston.

The self-imposed austerity that we often associate with Thoreau’s tree-hugging ways was, in fact, a means of understanding those individuals who had to eke out a meager existence on the outskirts of society. This does not make Thoreau a saint, but it does suggest an intimate connection between Thoreau’s retreat to the woods and his ability to understand those suffering under the conditions of oppression.

So who exactly were Thoreau’s neighbors?

As Lemire and Walls discovered in researching Thoreau, these individuals embodied the fraught history of race in the Americas. Brister Freeman’s sister, Zilpah White, was also a freed slave. After the Declaration of Independence was defended, she lived on the edge of Thoreau’s famous bean field, the place where he toiled for two years in the hopes of realizing Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance,” the rare and difficult act of supporting oneself.

Lemire explains that Zilpah White did it without fanfare. She wove linen and made brooms for a living. Arsonists burned her house down in 1813. She managed to escape the fire, but her dog, cat and chickens died. She rebuilt her home. But her life — and life for women like her — didn’t have much in common with Rousseau’s Romantic ideal of the state of nature.

And then there were the pale-faced, redheaded citizens of Walden Woods who didn’t quite get to be white, the Irish. The Irish immigrants who came to the United States in the first half of the 19th century were, for the most part, ghettoized in the borderlands of society. Thoreau, however, sustained long and meaningful relationships with the many Irish immigrants who came to live and work on the railroad line near Walden.

Walls discovered that Thoreau met an ailing Irish ditchdigger named Hugh Coyle and offered to show him a clean spring that ran near Brister’s Hill. But the old man was too sick to make the short trip. He, like so many Irish near slaves, drank himself to death in abject poverty.

By the time Thoreau came to Walden on July 4, 1845, most of America’s untouchables were gone, but the traces of former slaves, squatters, immigrants and day laborers were everywhere. John Breed, another impoverished worker on the outskirts of Concord life, lived in a small house just a stone’s throw from the pond. In Walls’s words, “Local boys burned it down in 1841.” At the age of 24, Thoreau raced from Concord to watch the fire, and conversed with Breed’s distraught son the next day. By that time, Breed himself was already dead: he too died drunk on Walden Road in 1824.

Thoreau was aware of the proverbial “nobodies” who occupied, and in many cases laid claim to, the land that he would later inhabit. Ralph Waldo Emerson purchased the cheap, mostly unoccupied and abandoned land around Walden where Thoreau would make his famous home from Thomas Wyman, a potter. Emerson would soon after invite Thoreau to build his writer’s retreat on this acreage. But before he did so, in April 1845, Thoreau bought the shanty of James Collins, a man who, Walls says, was an “Irish railroad worker moving up the line.” Thoreau paid $4.25 for the house (about $150 today). At dawn, the Collinses moved out, all of their belongings wrapped tidily in a small single parcel. Thoreau disassembled their shanty, bleached the boards, and used them to construct his cabin in the woods.

“Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity” — Thoreau embraced Spartan living as a matter of choice, but the irony of him tearing down a shed in pursuit of his much-celebrated modest way of life is a bit painful. It’s easy for us to judge Thoreau today; the privileged white man who plays at living austerely (choosing some “alternative way of life” that has been imposed on others) is a familiar target. But Thoreau himself was aware of this. Walls, for example, believes that Thoreau was probably helping the Collins family escape a lien on their house.

Thoreau recognized that he had every advantage; he also knew that the disadvantaged went, generally speaking, unnoticed by people of privilege. Social justice was in no small part a matter of counteracting this myopia, of recognizing suffering of others hidden in plain sight.

For Thoreau, what keeps the rich from understanding the plight of the poor is, in part, the fact of their richness, their stuff: not just metaphorically or conceptually, but literally. It’s hard to understand the inner lives of others if you’re always going shopping or looking after your household business or rushing off to parties. To “live deliberately,” in Thoreau’s words, was to wrest oneself from the diversions of this rat race, to understand the difference between the seemingly urgent matters of spending and acquiring and the truly significant ones of caring and thinking.

“Do not trouble yourself much to get new things,” Thoreau instructs us. “Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.” To be free from the distractions of modern life — of the endlessly diverting display of the ordinary, social world of stuff, stuff and more stuff — allowed a person to focus and think. What could we think if worldly possessions didn’t occupy our thoughts? What and whom could we attend to if we stopped attending only to ourselves?

Thoreau is often portrayed as a hermit, a lonely individual who rejected all forms of community. He was, in truth, happy enough to abandon the formalities and luxuries of conventional life, but only in an attempt to participate in a wider natural and social order.

This was a man who communed with the trees, spoke to bean fields, and conspired with the rain and sunshine that fed his crops. Yes, he had woodland friends. Many of his human companions were equally unusual: John Breed’s son, a day laborer, who lamented the destruction of his boyhood home; Perez Blood, the eccentric astronomer who Thoreau visited repeatedly on the outskirts of town; Sophia Foord, the brilliant spinster who fell in love with the one man, Thoreau, who rivaled her in peculiarity; the unnamed fugitive slave whom Thoreau escorted to the railroad station so that he could make safe passage to Canada. Countless others.

Part of embracing Thoreauvian wilderness is to open ourselves to individuals and groups who exist beyond the town limits. These were outsiders, unknowns, even outcasts, and Thoreau acquainted himself with them, came to understand them and spent part of his life caring for them. Thoreau entreats us to open our eyes to everyone. If he appears reclusive perhaps it is because we fail to see the significance of his companions — it is perhaps because we are not ourselves reclusive enough, or, for that matter, social enough in the Thoreau’s peculiarly intimate way.

In 1945, a century after Thoreau made his home on the banks of Walden Pond, Ralph Ellison began to write “Invisible Man.” “I am an invisible man,” Ellison’s black narrator explains. “I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

This refusal, whether conscious or not, is nonetheless, strategic: a way to superficially erase the injustice that silently underpins progress and affluence. The Native Americans of the Merrimack Valley vanished first to make way for the settlers — then the workers and slaves who supported the nation and the even-then-affluent Concord. What remains is the myth of the rugged, forward-looking individual fitted precisely to a country that would rather not retrace its questionable history. This, however, was never Thoreau.

“There are few things “in this world as dangerous as sleepwalkers,” Ellison wrote. Eyes closed, oblivious to the world, they proceed at their own peril, but more tragically, the peril of invisible others. If you rise before the sun and travel to Walden Pond, it is easy to understand the advantages of keeping your eyes open. We must, according to Thoreau, “reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us even in our soundest sleep.”

To take Thoreau’s example, however, is not simply a matter of appreciating the natural world, of taking careful note of every woodchuck and birch. It also involves looking into the trees, into the near darkness, to discern the hidden, human figures who silently abide there. And slowly disappear.

______________________________________

John Kaag is a professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, and the author of American Philosophy: A Love Story.”

Clancy Martin is a professor of philosophy at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.