The Universalism of Imam Moussa Sadr: A Relevant Approach to Contemporary Uncertainty

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 4 Sep 2017

Raed H. Charafeddine | The Yale University Council on Middle East Studies - TRANSCEND Media Service

Introduction

The Arab world is the geographic, historic and cultural point of convergence of the Muslim World. Islam was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the Arabic language in the Arabian Peninsula and, from there, the message spread across the world. The abodes of Islam remain platforms for debate and incubators for tensions and conflicting ideologies despite the passing of fourteen centuries since the Revelation. Certain issues of contention date back to the earliest years of Islam and have, remarkably, gone unresolved to this day. Such issues include succession (the Caliphate) and alternation in power, the separation of religion and State, innovation (Ijtihad) and imitation (Taqlid), and much more. Exploring these issues is no mere intellectual luxury. Even today these are still pressing matters as current political situation is mired in turmoil, uncertainty, and lack of vision.

The current political challenges result from three main issues:

- The violent activity of certain extremist factions bedevils the region. In areas of the Middle East, pockets of poverty and exclusion prevail and provide fertile ground for fostering such factions;

- Oppressive regimes and feudal monarchies have seen the most serious expression of popular dissent, although fledgling opposition movements have so far failed to organize and present viable institutional alternatives offering a vision and a platform;

- Petro-dollar surpluses have been squandered and the promise of true development has failed to come to fruition in any of the countries of the Middle East. In fact, these surpluses contribute today to leveraging marginal powers over the historical centers of influence, favoring an opportunistic approach.

For many, the worst scenario revolves around two major threats:

First: The mass exodus of the Christian communities of the Middle-East thus divesting the region of a civilizational component, a guide for humanity and its salvation, and shifting it towards the doom of “the clash of civilizations”;

Second: The Sunni-Shiite sectarian strife and the deep-seated nightmarish images it brings up in collective memory with its devastatingly divisive repercussions on the Islamic people.

An observer of developments across Arab countries (and extensively, Islamic ones) can note growing preoccupations at multiple levels:

- How will these communities overcome the period of violence and shift to situations that preserve the right of the people to life, dignity, and freedom?

- Rising concerns about the conditions of vulnerable groups, such as women and religious/ethnic minorities;

- communities and peoples caught in the tide of international interests which tug them in competing directions.

All these factors – and there are certainly more – add to the confusion. Urban populations suffer from increased socio-economic and security concerns, with the political impacts of the current turmoil in the region still to be fully realized, along with inter- and intra-faith conflicts adding to the fears of minority groups. The voices of wisdom have grown faint and the mechanisms of dialogue all but non-existent.

These issues preoccupied Imam Sadr to a great extent. He believed that Lebanon possessed most of the grounds, conditions, and opportunities which keep such risks at bay or at least allow their repudiation. In fact, Lebanon, in its history, composition, and experience, is at odds with the bitter events sweeping through the region. It is the antidote.

This paper addresses these topics and reveals how Imam Moussa Sadr foresaw, as early as the 1960s, the threats we are facing today. After touching on the concept of universalism, we will discuss how it has been addressed within Islam as a whole and by Imam Musa Sadr in particular. Then, we will examine how Sadr saw in Lebanon a bearer of civilization to the world, based on the country’s confessional and cultural diversity, and called for dialogue as a means to build a human community that strives for perfection. He established a participatory approach to development, reflecting faith in humans and their capabilities, beginning with the restoration of confidence in oneself and in others.

Universalism as Concept

Universalism, philosophically speaking, expresses those truths which apply to all people and at all times. Universalism, from an ethical point of view, is the system of values shared by all people. According to Chomsky, universality is “one of the elementary moral principles, that is, if something’s right for me, it’s right for you; if it’s wrong for you, it’s wrong for me. Any moral code that is even worth looking at has that at its core somehow.i” Universalism, in general, bespeaks all that is intrinsic to human beings by their very nature.

From a religious perspective, Christianity is based on the premise that Christ died to save all of humanity. Islam, in turn, is for all, {And We have sent you not, but as a mercy to all creatures} [Al-Anbiya (Prophets)/107], said the Lord to the Prophet (PbUH). The Islamic doctrine is based on the principle of progress and build-up of prophetic message and knowledge, where revelation encompasses all that was expressed by God from the days of Adam, to Jesus, concluding with the Prophet Muhammad (PbUH).

It seems remarkable how the early Muslims managed to draw on the sciences, arts, and literature of their predecessors, expending considerable efforts to acquire, translate, and develop such works then disseminate them widely in all places where they settled or had access to. One only has to imagine the trading activity they launched across their vast empire (Al-Mamun ordered a map of the world be made) to recognize them as among the true pioneers of globalization. We also note the Golden Rule maxim, common to most religions, including Hinduism and Confucianism, which simply exhorts one to treat others as one would like others to treat oneself. In language and communications, universal and universality are used to characterize anything having broad scope and wide reach. In legal terms, what first comes to mind is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which is built on the universal construct of ethical codes being applicable to all human beings. All human beings have rights. They are all entitled to the same rights.

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the concept of relativismii, which concedes that all points of view are, in principle, valid. Here, anthropologists distinguish between the various cultures of the world and the distinctive characteristics and traits particular to each. We may also speak of particularism versus universalism. While universal cultures promote written rules and procedures, particular or distinct cultures focus on relationships, their nature and solidity. They consider that distinctiveness – especially in the world of business and transactions – trumps written contracts and agreements, and that agreements are built on the basis on interpersonal trust and develop with the evolution of the relationship.

All that is “universal” reaches, in its impact, beyond the spatial or time frame from where it originated. Students of Imam Sadr’s works note that his choice of Lebanon as a field for his work stems from his belief in the validity of this small country as a universal model, where its experience may be generalized and disseminated, especially on matters of dialogue and coexistence.

1. Universalism in Islam

1.1 What Is Islam?

Islam is the monotheistic submission to God of one’s entire being. It aims to regulate relationships between people and the world they live in. The particularity of attributing Islam to the message borne by Muhammad (PbUH) is that, according to Islam, Allah’s messages ended with Muhammad. In Islam, the messages that preceded that of Muhammad (PbUH) were stages of divine revelation, where each prophet expressed the message according to the awareness and education of the people. As such, each prophet called for monotheistic worship in a way that corresponded with the era in which the message was revealed.

The Prophet Muhammad (PbUH), submitted himself to God as did Abraham, the father of all prophets, and his descendants. This means that all that prophets uttered, from Abraham through Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, to Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad is but one message. {Or were you witnesses when death approached Jacob, when he said to his sons, What will you worship after me? They said, We will worship your God and the God of your fathers, Abraham and Ishmael and Isaac – one God and we are Muslims [in submission] to Him} [Al-Baqarah/133].

Islam offers perspectives on many concepts including labor. Labor becomes a form of worship when suffused with dedication, on life and the hereafter, on the body and the soul, good and evil, on virtues and vices, on what is lawful (Halal) and what is not (Haram). Islam, similarly, prescribes the meaning of prayer, fasting, and other devotions. These are not undertaken to curry His favor, or for His benefit, neither are they meant to appease His wrath, nor for His edification, but rather out of freedom from all else but Him. “My Lord, I did not worship you for fear of Hell, nor for a desire of Paradise; rather I found you worthy of worship” [Imam Ali Bin Abi Taleb (PbUH)].

This is Islam, God’s faith under its many names and the many paths taken by the messages calling for His worship. Perhaps it is not too much of an extravagance to say that the vast majority of the intuitively Muslim [those in submission to God] would define Islam [submission to God] as we have previously done, regardless of whether the present climate of anxiety and violence distorts the intuitive meaning in other directions.

Islam: Theory and Practice

The extent to which Islam’s theoretical concepts respond to fast-paced change and developments can be described in terms of three schools or trends iii:

- Orthodox, fundamentalist, or radical Islam which resists adaptation and interpretation, and demands literal adherence to religious texts; resurrecting rites, customs, and practices that were common in the days of the Prophet, at the time of the Revelation; and following their example in addressing contemporary social, and religious matters;

- Syncretic Islam which has adapted to context and circumstances, as observed in Indonesian, Moroccan, Malaysian, and Turkish cultures. This school of thought suggests that Islam was able to impress its mark on the peoples of these countries without eradicating their cultural and ethnic traditions;

- Open Islam based in Ijtihad which calls for a renaissance of the Islamic community by interpreting religious texts to respond to the challenges of modern times and the social, institutional, and cultural structures they have generated.

This diversity and sometimes competitive nature of religious practice and interpretation raises a number of cognitive and descriptive problems. Essentially, they represent difference between Ijtihad and Taqlid. According to Jamal Eddine Al-Afghani, blind and rote imitation of the acts of our ancestors leads to dullness of mind and decrepitude, it bespeaks stupidity and stasis. Modernist Muhammad Abduh calls for liberating humankind from the stasis of Taqlid. He does not oppose drawing religious knowledge from its sources but emphasizes the need to combine it with the capacity for rational thought that God has endowed us with. Human beings, through reasoning, wed science to faith to uncover the mysteries of life.

Moving away from an Islam bound to a specific time and place towards a universal Islam constitutes a shift from the “sanctity” of Taqlid towards the broad horizons of reasoning and Ijtihad. This opens multiple horizons, as the schools of Ijtihad are indeed many, and may be classified, for the purposes of this discussion, under three headings:

- Enlightened Sharia that is open and steeped in Ijtihad, by which many claim that the Prophet Muhammad (PbUH) gave, in his day, an express pledge to non-Muslims in Madina, i.e. he recognized their rights and vowed to guarantee them. Turkish writer Abdul Rahman Dua goes as far as to suggest that the Holy Quran is the world’s first written constitution;

- Lacunas, as expressed by the martyred Muhammad Baqir Sadr: those paradigms and topics that still have not been addressed by Sharia. They are, according to Egyptian scholar Salim Al-Awa, the responsiveness to change, circumstances, and events demanded of Muslims by Sharia. The Quran is a collection of general principles and guidelines, intentionally giving people freedom in working out details and procedures. It is not incidental that Sharia does not favor a certain kind of regime or specific mechanism for ruling, as if it were urging people to grow and evolve and change through constant search and innovation;

- Multiple interpretations of Sharia : Difference and multiplicity in Islam are stated elsewhere, and this multiplicity is important and valued in Islam. While revealed faith is divine and one, theology is human and many. The multiplicity of theological debates at once allows and justifies communication between its branches, resulting in transcendence to more perfected stages of humankind’s evolution.

Islam and Ijtihad The interpreter (Mujtahid, from Ijtihad) is no legislator, nor is he a modifier of the laws of Sharia. He rather studies and invests his energy into eliciting a ruling and applying it to the issue at hand. What is required is to address the issue, the nature of which changes with the times and as societies develop. The Mujtahid, after having examined an emerging issue, attempts to derive his ruling based on evidence and the sources of Sharia. Often, the issue is new; there is no precedence that can be found in the days of the Prophet or the Imams. The Mujtahid tries to deduce his ruling from general laws and comprehensive principles. Thus, the role of the Mujtahid is to understand the divine ruling on the issues, not that desired by certain interests and particular circumstances.

The purpose of the Mujtahid’s endeavor is to derive his ruling from general laws; the ruling is the fruit of effort, search, and reflection on the Holy text. It is not merely adopting the text as is, and establishing it as ground for ruling without considering the available body of general texts and laws. This activity, therefore, is an exercise in channeling one’s mental faculties, alongside the text, to make the elicited ruling applicable. Here, we find that the process of Ijtihad is a wellspring for the Islamic jurist (Faqih) and a guiding light. It should be noted that the role of the Mujtahid is different from that of the modernist (Muhaddith) where the Muhaddith conveys, but the Mujtahid invests himself – his own judgment – into the facts. The Mujtahid’s role is also different from that of the legislator (Musharri‘), as the latter responds to interests and living conditions by drafting laws. The Mujtahid is expected to demonstrate an independent spirit, free from the authority of jurists, unbound by the Fatwas of others, unabashed in opposing prior Ijtihads.

In the words of Imam Sadr, (Ijtihad is an intellectual process, an independence of opinion, a movement towards applying elicited rulings to modern life, while maintaining the divine framework of the rulings. If Ijtihad fails to abide by this framework, the religious ruling loses its purpose and basis because the fundamental element about religion is that it is divine and comes from God. If we were to stray from God and derive rulings according to circumstances and interests, the rulings cannot be deemed religious; they have become the laws of men.iv)

For Muslims, universalism within Islam clearly remains an issue of debate.

2. Imam Moussa Sadr and Universalism

Sayyed Moussa Sadr*’s family tree extends all the way back to Imam Ali Bin Abi Taleb and his wife Fatima Al-Zahra, the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. This lineage occupies a special place in the heart of Shiites and an honored status among Muslims in general. Their pedigree, as recorded in genealogies and biographies, allowed the men of this branch to assume, in the realm of theology, a position of utmost prestige in their time. What distinguishes them is a preoccupation with guidance and research without neglecting public affairs and the concerns of the people. This commitment made them the target of the rulers’ wrath, and exposed them to all forms of oppression and persecution; some were imprisoned, and some were sentenced to death. Even as rulers continued their campaigns against them, their role as leaders grew amid their supporters, especially the disadvantaged among them. Thus, leadership came naturally to them in both religious and public matters.

For these reasons, members and whole communities of the Sadr lineage migrated to areas from Egypt to India. In the 20th century leadership settled in Tyre (Lebanon), in Najaf and Kadhimiya (Iraqi capitals of theological study), and in Isfahan and Qom in Iran. Each generation of leaders was conscious of the scholarship and social role of other leaders. They communicated in writing but had few meetings in person. When Imam Sadr, not even 30 years old at the time, visited his family in Tyre in 1955 he found himself among people who knew much about his scholarship and inclinations. His return to Tyre, in 1960, to assume the responsibilities left behind by the passing of one of the great figures of the family as the religious authority of the Shiites of Lebanon was a natural realignment, as though there had not been a gap of 175 years since his ancestor left Lebanon and his own return to the country.

2.1.The intellectual pillars of his life and career

2.1.1. Peace is of the Essence in Religion

The Muslim faith commands its followers to submit (Islam) in peace completely. The salutation of Islam is a greeting of peace (Salam). Peace is one of God’s holy names and revered attributes. Peace is reflected in the world and evident in His Creation.

(Religions were one, for the starting point is that God is one, and the end, which is humanity, is one, and the setting, which is the cosmos, is one. When we forgot the purpose and moved away from ministration of humanity, and we forgot God, we became many factions and took many paths. Discord was sown among us and we quarreled. We divided the one cosmos. We served private interests. We worshiped gods other than God. We crushed humanity and it rent apart.)v Imam Sadr adds in the same sermon:

(Religions were one and had one aim; fighting mortal gods and earthly tyrants, championing the weak and oppressed. And these too are two facets of one truth. When religions won and the weak won alongside them, they found that tyrants had changed their cloaks and raced ahead of them to plunder the gains. They began ruling in the name of religion and started wielding the sword of religion. The crisis grew worse for the oppressed and the crisis of religions and religious disputes emerged, although there is no dispute other than the dispute over the interests of the exploiter.)vi

Imam Sadr’s message, on this and other occasions, was extolled at the Vatican and in Europe, which prompted the papacy to invite the imam to attend the induction of Pope Paul VI, in the early sixties. In fact, Imam Sadr was the first Muslim scholar to have witnessed such a ceremony at the Vatican. There, he spoke at length of the role and message of Lebanon…

2.1.2. Human Dignity is the Common Human Standard

A curious mind wandering the depths of Sadr’s philosophy can deduce the fundamental elements of human dignity – freedom, safety and security, work, and brotherhood – as practiced and promoted by Imam Sadr:

Freedom – freewill as precursor to excellence: Imam Sadr believes that human beings are free in their actions and decisions, that they are called to learn throughout their lives. He explains the role of the prophecy in creating a righteous society and sound way of life. Religion and all that is good are intrinsic to human beings. Deviating from general rules is “acquired”, meaning that it comes to people from without and is not inherent to them. The Imam highlighted respect for the dignity of human beings, whom God Himself dignified, and the dignity of all they do. (The first step in educating people and promoting excellence in all areas is to make them aware of their dignity, allow them to handle their affairs; otherwise they will fail to attend to themselves, and will expend no effort in redressing their situation.vii)

Freedom is the best way to liberate all the potentials of a person. An individual cannot serve his mission in a freedom-less society. They cannot unleash their capacities and nurture their full talents if they lack freedom. Freedom is the recognition of human dignity, it is having good faith in humanityviii.Freedom of religion is a fundamental human freedom. Islam enshrines the freedom of opinion and worship in keeping with the verse {there shall be no compulsion in religion} [Al-Baqarah/256].

Security and Safety – prerequisites of growth and development: Islam respects human life, and considers saving one’s life as saving humanity as a whole, and the intentional ending of one life as the ending of all human lives. {Whoever kills a soul unless for a soul or for corruption [done] in the land – it is as if he had slain mankind entirely; and whoever saves one – it is as if he had saved mankind entirely} [Al-Maidah/32]. Islam asserts the need to preserve the lives of others and warns those who neglect the affairs of their poor and orphaned, resulting in the death of any of them from destitution or disability. It is stated in the Hadith that ((the villagers were abandoned by God and His Messenger)) for having betrayed God’s trust, and broken His covenant when they failed in their responsibility towards each individual life. What is said of the village is also true for cities, nations, and all the corners of the world, which constitute an integral whole. Imam Sadr observes that only by rejecting the control of a person over another human being is one truly free. Honoring spoken and written promises, pledges, conditions, and agreements preserves the sacredness of one’s word.

Work – human synergy and growth: Imam Sadr illuminates the importance of work in Islam: (People’s work is the only force capable of making history, of driving it along and causing it to evolve (…) The only protagonists on the stage of history are people, molding it, advancing it, moving it along, while themselves advancing and moving and interacting just so, constantly (…)ix) He subsequently classifies work ethics and their influence on ensuring sound relationships, as Islam affirms that work is sacred and virtuous. Sadr also addresses the efforts deployed by people without visible recompense, saying that Islam does not see such efforts as having been in vain, they are rather an experience upon which future outcomes are built or are remembered by God. Futility is not in failing to achieve one’s goals, but in wasting potential when an essential aspect of human existence is denied, or is disproportionately developed at the expense of another. In both cases, society loses the talents, potentials, and competencies of its members, and is weakened by the weakening interaction of individuals and society.

Human Beings Are All One and the Same – herein lies excellence: What is meant here is that we are all one species, rather than one gender. Therefore, Imam Sadr focused on honoring women and men, and on enlarging their opportunities to fulfill their particular and universal rights. Individual and societal dignity is shaped through education and developing a sense of individual and collective responsibility. The depiction of humankind in the works of Imam Sadr is not hemmed in by any boundaries. When reading what he says about humankind, and what he wrote about the cosmos, it is as though the individual has turned into the cosmos. Not only does he claim that humankind reflects the cosmos, he elevates humankind as the sole image of an unfathomable will, uniform and enveloping all existing matter and creatures as the entity that brought them into existence and creation.

People as Actors and Agents: Each person has the right to belong to a specific human community having its own identity, structure, and values. (Working in accordance with common principles is not considered politics; I see it as part and parcel of my responsibilitiesx. I am not a politician, neither am I an administrator. I do not propose an alternative for the existing regime or those called for by the various factions. I am a cleric. My involvement in this crisis [the beginning of the civil war in Lebanon] is the involvement of a citizen who feels that his country is at riskxi. I do not believe in labeling people at all. I do not act on the basis of political affiliation unless the fundamental values of people’s lives are endangered by their affiliations.xii)

(In their constitution, their life, their needs, consciousness, thought processes, and all aspects of their existence, people are social creatures interacting with the society they live in. How can they, then, isolate their faith, ethics, and personal deeds from the interactions of their community when the two are inseparable?)xiii

The human community, for Imam Sadr, has its advantages, namely (the diversity of competencies: just as people differ in appearance so they are different in their mentality, their dispositions, and competencies. The diversity of human beings makes the current flow back and forth between one individual and another.xiv) Moreover, (people are faced with goals and gains which are greater than the individual, such that the individual alone cannot achieve such goals nor attain such gains alone. Therefore, the individual needs to cooperate with others to gain strength and be capable of realizing such objectives and meeting such goals.)

2.2. Imam Sadr on Ijtihad

We have already touched on the issue of Ijtihad in Islam in general, and among the Shiites in particular. We recall that Ijtihad consists of the Faqih’s rulings that do not deviate from the spirit of the holy text but provide solutions that accommodate the culture and ideas of the age. Below are examples of Imam Sadr’s Ijtihad:

2.2.1 Rituals

On the mechanism for determining the beginning and end of the lunar cycle, which is followed by all faiths for assigning the dates of their liturgical seasons: Muslims had typically relied on visual sighting in their Ijtihad concerning the first signs of the crescent moon (Hilal). Imam Sadr, meanwhile, accepted the linguistic meaning of the term “sighting”, i.e. both vision and discernment. He adopted the latest scientific developments in advanced optical detection instruments (telescopes of various sizes and strengths) and mathematical calculations of cosmic and astrological movements. He then released a Fatwa on the possibility of employing science in determining lunation. As for “witnesses”, who are supposed to be experts (Shuhud Udul), he found that communicating with and soliciting information from reliable Muslims all over the world facilitates the task of validating the sighting of the crescent moon by the lawful administrator of justice (Hakem Sharii).

2.2.2 Interdependence

On explaining the term Tahluka, which is mentioned in the Quran, is generally translated as ‘destruction’, and is considered as life threatening, the holy verse states {Spend in the way of God and do not fall into destruction} [Al-Baqarah/195]. The injunction had been used in a dispiriting fashion, discouraging the duty to defend land, honor, and people. Imam Sadr, however, highlighted the context of the verse and connected its meaning to what came before and after it in Surat Al-Baqarah and in other Surat. He derived an innovative explanation, suggesting that the destruction referred to is primarily social. Indeed, it is the duty of those who possess material resources and intellectual potential and live in comfort amidst the backwardness of other human beings to strive towards improing their milieu. Refraining from doing so leads to further regression in society, which adversely reflects on them, while the prosperity of society positively reflects on making wealthy and comfortable as large a number of people as possible.

2.2.3 Zakat

On the issue of alms (Zakat), or the dedication of a portion of annual income as charity to redeem oneself before God, some are taken out of net profit, and some are deducted from the assets possessed by a person. There are other forms as well, of course. The money is offered – to redeem oneself – to the appointed authority or their delegates in Islamic countries. There are numerous such authorities, and their delegates are many indeed, thus generating confusion in dispensing the funds. This prompted Imam Sadr to argue for the establishment of a Zakat Fund where all alms are collected and recorded in accounts that disclose the sources of the funds and how they shall be spent. The Fund would be organized in the manner of social security, where resources fund the medical care or education of the needy, support them in expanding their livelihoods, serve as old-age pensions, and provide other services called for in Muslim communities.

Perhaps the imam’s boldest Ijtihad are those on bridging the gap between Muslim denominations and promoting inter-faith dialogue. Not only do these Ijtihad address chronic sensitivities, they touch on central issues facing us today; what with concerted efforts to mask the greed of foreign interests and power struggles and paint sectarian disputes and ethnic diversity as culprits in crises. Researcher and Muslim-Christian dialogue activist, Muhammad Sammak notes the existence of an official letter from Imam Sadr, indexed and archived at Dar Al-Fatwa in Lebanon, calling for “unifying Fiqh, unifying the rituals of worship, even unifying Adhan and religious feast days, and creating special committees of Sunni and Shiite Muslims to settle these details; and we shall abide by the recommendations of these committees.xv” This attention to details reflects his astute awareness of their role in mending or widening the rift between people. Thus, Imam Musa Sadr offered his Ijtihad to serve religion and the people. His Ijtihad represent an integral vision of how people should be, their life journey, their purpose in society, indeed the cosmos.

The vision of Imam Sadr may be summed up as follows:

- Religion is for the happiness of people and the people are the reason and purpose of religion, individually and socially;

- People’s faith is meaningless if not coupled with deeds;

- Reality as lived by humans and the holy text are in an evolutionary, enriching relationship;

- Enlightened Ijtihad allows interpretation, is in step with progress, and preserves the sanctity of the holy text;

- A person is an integral whole: a meeting of the various human dimensions, individual, social, natural, and divine.

These are the pillars of Sadr’s legacy which he adopted as a methodology for his life and work. In addition to scholarly endeavors, Sadr was distinguished in his commitment to application and the need to disclose and disseminate outcomes. “He constructed a vision and carried it among the people, rallying them to action. And he did so alongside them, indeed as one of them. He was able to motivate them towards fulfilling their needs and purposes, and to develop and adapt his vision based on his interaction with the people.xvi”

This man who always strove for perfection needed a platform for action through which his succession as God’s steward would be revealed. Lebanon was an excellent arena for his movement. What tangible and institutional outcomes did he bequeath us?

2.3. The Universalism of the Lebanese Model

2.3.1. Imam Sadr and Lebanese Plight

Over less than two decades (1960-1978), Imam Sadr traveled all over Lebanon and carried the concerns of the country and the region to most capitals of the Arab world. The social mobility which he spearheaded and the centers, bodies, and the various organizations he launched created a historical turning point, the results and manifestations of which still reverberate to this dayxvii. Poverty belts were besieging the cities of the fat and prosperous 1960s. The seeds of civil war had found fertile soil in which to grow in and had begun to bloom under various regional and global factors and conflicting interests. Those belts in particular were a platform for political, social, and developmental action for Imam Sadr who, early on, realized and warned about the explosive dangers festering within these impoverished communities. The suffering and turmoil in later years would prove him right. He was the first to sound the alarm about the consequences of injustice and neglect on the people, the country, and civilization. It was not coincidental, then, that he would be among the first to fall victim to the dark clouds of conflict that settled over the country, and many others would experience the same fate as the storm swept everything in its path.

There are many well-known accounts about Imam Sadr in Lebanese lore, propelling him to the status of role model as well as inspiring nostalgia and grief for his loss from the Lebanese arena. With Sadr at its helm, As-Safa Mosque in Beirut turned into a platform of jihad, a bold cry for peace, and refusal of civil strife. This site of protest became a pole of attraction drawing in thousands of officials, spiritual leaders, and citizens. Sadr did not end the sit-in until the siege was lifted from the beleaguered Christian villages in the Beqaa. At another time and place, he learned that the Muslim residents of Tyre were boycotting an ice-cream vendor because of his confessional affiliation. Prompted by the incident, he followed on a Friday prayer with a popular march. The masses followed him. He led a popular march in support of the vendor after a Friday prayer: he tasted his fare, and the corwed followed suit.

Under the sway of tribal customs, acts of revenge and bloody disputes were common among the clans of the Baalbek and Hermel regions of Lebanon. Such practices were damaging to the image of the area, spread fear, and spoke of cultural backwardness. They also created a tense situation for the government whose security services sometimes fell victim to the disputes. The Imam always initiated reconciliation, interceding in the name of all tribal traditions and systems to make peace and have the local leaders sign a pledge to that effect. Whenever the government got involved, he also intervened to preserve the dignity of the State and the enforcement of public laws, while urging the government to build the infrastructure needed to shift the tribal way of life into peaceful, civil coexistence.

Until the date of his disappearance in Libya, Sadr continued to address all Lebanese, hoping that his voice would rise above the sound of bombing, shelling, and explosions: (A country lives in the conscience of its people before living in the realm of geography and history. There is no life for a country without a sense of citizenship and participation. This should be clear and always evident in the dismissal of favoritism based on kinship, ethnic minority, confession, and political affiliation xviii).

2.3.2. The Enduring Discourse

“Lebanon is a final homeland for all its people,” so begins a working paper presented by Imam Sadr in 1977 to the President of the Lebanese Republic Elias Sarkis, two years after the civil war erupted in Lebanon, in a bid to solicit proposals for reforming the situation in the country. His statement was later adopted in the opening of the Taif Accord in 1988. It was also featured in the preamble to the Lebanese Constitution which was amended pursuant to the aforementioned agreement. It was his hope that all Lebanese citizens and institutions – people, Parliament, Government, and Presidency – would acknowledge as the one central truth that comes from an unshakable faith in Lebanon and that it would constitute the cornerstone of renaissance in the country.

([My hope] is for voices to rise from the North of Lebanon in defense of the rights of the people of the Beqaa, that calls would resound in the Mount Lebanon to build back and defend the South, that wealthy households and individuals in particular would strive to improve the living standards of the tired drudgers and dispossessed, that one denomination would denounce and demand the end of sectarian discrimination inflicted on another denomination. This is true citizenship and this is the means for the survival of any countryxix).

Imam Sadr endeavored to always be transparent in the path he chose, and the majority of the people of Lebanon acknowledged that he was true to his words in his deeds: (Clerical responsibility does not exempt me from good citizenship and its obligations. Belief in God, striving to preserve the country, and upholding human dignity are at the heart of the average citizen’s duties.xx)

Imam Sadr’s accomplishments and career garnered the attention of observers and researchers abroad. Imam Sadr was dubbed an “interfaith hero” by the American writer reverent Daniel L. Buttry who noted: Imam Moussa Al-Sadr was the leading Shiite Muslim figure in southern Lebanon during the 1960s and 1970s. He was especially concerned about eradicating poverty and stimulating education for those who were disenfranchised by the main social and political systems in Lebanon. He founded many social institutions, vocational schools, kindergartens, health clinics and literacy centers. { …} He personally led a fast for peace and a public demonstration to halt the siege of Ka’ village and Dayr al-Ahmar Village, two Christian communities.xxi”

2.3.3. On Lebanon as a Bridge between Civilizations

Perhaps the size of the country chosen by Imam Sadr as an exemplary model, Lebanon, is incongruous with the term “universal”. But his legacy and his understanding of its depth are universal. From this deep understanding came the universality of the desired impact and the cosmic passion expended. His vision for humanity is comprehensive, and the individual, natural, social, and godly threads or aspects bind people together. On Lebanon as the bearer of a world civilization: (As a result of the communication technologies and the expanding travel network, the world, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, has become one country. The longest distance between any two countries in the world is no farther today than the travelling distance between Beirut and Tripoli. Therefore, this interconnected world, which encompasses religions, and the coexistence of the peoples of the world, allowing humanity to pursue the building of one cosmic State, to a great extent depend and are influenced by the success of the Lebanese formula for coexistence.xxii) (Arab-European dialogue, given Europe’s experience, history, and position, and the Arab World’s cultural heritage, resources, and geographic location, is a source of great hope to the world today in producing political forces whose locus is Christian-Muslim dialogue. If the Lebanese experience fails, human civilization will be doomed for at least a half century. Hence, we assert that Lebanon is now, more than ever, a civilizational necessity.xxiii) What is the link between Arab-European dialogue, the locus of which is Lebanon, and the reinvigoration of civilization across the world? Turning back to the title, the conceptualization of Lebanon’s influence, one of the world’s smallest countries, on a global civilizational movement calls for some examination and exploration.

Imam Sadr liked to reiterate the importance of Lebanon’s unity, as a land and people. This country has a population of four million, containing 18 sectarian denominations, in a country of barely ten thousand square kilometers! In contrast, we find the public image of the people of Lebanon to be educated, adventurous and worldly – while the political, economic, scientific and artistic relationships generated by the diaspora contributes to the spreading of Lebanese influence globally…a dynamic that can be harnessed by Lebanese citizens and expatriates alike. The Imam described this dynamic as a “site”, a “locus”: if the country were to unite its domestic and international potentials and relationships, it would produce – from the perspective of liaising potentialities – a situation that is unique.

In order for Lebanon to be a bearer of civilization to the world, the Lebanese people should shape their course by drawing on the prerequisites of good citizenship. (If national consensus was attained and Lebanese governance and visions were instituted, the brightest future would be within our reach. We cannot trust in predestination, history forbids it, so do faith, which is the source of reasoning, and our beating heartsxxiv. We want Lebanon to be Arab, not a foreign body in the region, with one-way exchanges. We want it to interact with its brothers, bearing with them its responsibilities as an Arab country, to participate in the fate of the Arab World, and to enjoy its full privileges. We want to break free from political hypocrisy and national inferiority complexes under the pretext of refusing to be pawns. We want to end our blind adherence to ambiguous slogans. We want an Arab, free, and independent Lebanonxxv.)

2.3.4. On Institutionalizing the Dialogue

The Supreme Islamic Shiite Council was founded by the Imam to work on realizing the potentials of the community and to set them on track with the rest of society. Shiites had been divided into belligerent forces, lacking a connection to preserve their efforts and channel them towards others. (Organization will lead to the coordination and harnessing of potentials, it will prevent the wasting of potentials and their clashing.xxvi) After listing the aims and missions of organization, Imam Sadr positions the Council to serve Lebanon. (It facilitates the mission of complete unity by means of dialogue, mutual understanding, and rapprochement; there can be no dialogue except between true representatives).

If the war was claimed to be between two religious camps, then who represents religion? Is it the belligerents or the spiritual authorities who convened at the headquarters of the Maronite Patriarchate in Bkerke on 4/10/1975? Participants in the conclave issued a statement in which they asserted that God joins believers no matter what faith they belong to, that He unites them when they take His teachings as their moral code. They denounced all forms of violence so that people can live peacefully and compassionately, connected to one another by spiritual values. They warned of the consequences of war, affirming the need to foreground reason and the directives of spiritual leaders and God’s faithful. Following the conclave, a meeting was held to announce the creation of the Committee for the Defense of the South, in which were represented all denominational leaders, with a view to protect southern Lebanon and preserve the dignity of human beings towards safeguarding the country as a distinguished bearer of God’s entrusted legacy.

Through these meetings, Imam Sadr highlighted the need to prevent further escalation, reiterating the statements he had made since his return to Lebanon and proceeding to help Shiites as equal contributors in the renaissance of Lebanon. (Sectarianism has more than one meaning. It may be political. Often, sectarianism means attending to the affairs of a sect. Others suggest that it means piety. However, sectarianism is perilous when it turns negative. Setting up one’s sect as a barrier to cooperation and interaction is baseless. This is another meaning, remedied through sound religious education, and the pure and uncompromising efforts of loyal souls. I believe that the people of Lebanon, if left to express their true nature are not sectarian in the negative sense. They wish to faithfully cooperate with their compatriots.xxvii) In order for this distinctive trait to transcend slogans and rhetoric, in order for it to become a way of life and a standard for communication, Imam Sadr practiced coexistence in his career and struggle. He was likewise keen on disseminating and employing the language of dialogue wherever he went.

Conclusion: The Importance of Sadr’s Legacy Today

Imam Sadr, nonetheless was not engaging in intellectual leisure or practicing some mental recreational activity in an experimentation field called Lebanon. He was struggling to prove his thesis, tirelessly and with his heart and soul fully poured into the endeavor:

- An observer of the realities of the Shiite community in Lebanon in the mid-twentieth century would find it marginalized, on the wane, and frustrated. Then came Imam Sadr, carrying the Shiites towards self-confidence and self-actualization, which would later allow them to trust others in order to build together a model nation and offer it as a legacy to a world growing more fractured. He prevented the formation of a tense, fanatical community, instead creating an entity that was communicative and engaged in the construction of a nation built on dignity, justice, and participation.

- Striving for truth, justice, and dignity in building Lebanon as a society, nation, and state does not, however, imply introversion, making Imams State leaders, nor turning the country into a Shiite community. Imam Sadr shed light on the plight of the dispossessed in unconscious and existential instances of historical unfairness, chronic neglect, ostracism, and other oppressive negativity and managed to turn them into positive energy reflected in revolutionary enthusiasm governed by the willingness to change into a virtuous and active society in the context of human civilization.

- Imam Sadr was keen not only to involve people in the movement for change but also to convince them of this movement and of proclaiming their approval (Baalbek Festival and Tyre Festival in 1974). This practice will prove beneficial for the rallied masses in Arab cities today. It requires a trusted leadership with clear objectives and a keenness to obtain validation from and the support of the people.

- The variety of Shiite authorities in the world, not to mention the concept of Ijtihad and the horizons it opens on acclimation and modernization, may serve as a way out of the crisis of power, leadership, and ruling mechanisms. The experience of Imam Sadr was never free from inspiration and experimentation. He opposed engaging in political action and refrained from presenting himself as a professional exercising authority in the technical sense. He exercised his power as a citizen entitled to lead, mobilize, and lobby in order to stanch dissipation and discrimination. He worked to reinforce good citizenship by promoting its two pillars: rights and obligations.

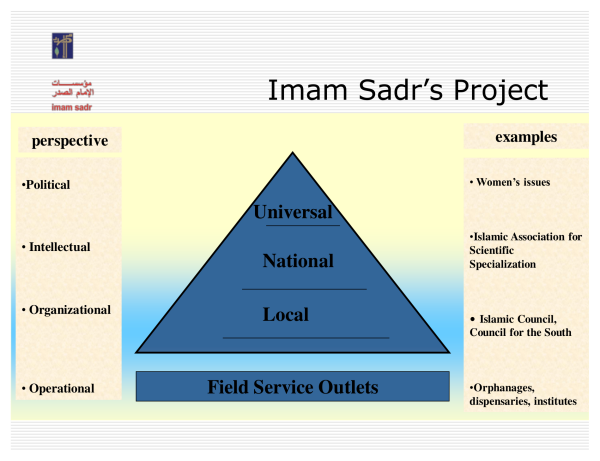

Finally, recalling the title of this paper – the universalism of Imam Sadr – the contribution of His Eminence may be represented in the shape of a multi-layered pyramid; a model implemented in the research department of the Imam Sadr Foundation in Lebanonxxviii:

- At the base of his accomplishments, from an operational standpoint, we find all the field service outlets: dispensaries, institutes, charity foundations, and schools;

- At the organizational level, Imam Sadr’s local contributions produced many institutional structures that ran the above facilities or managed regional or circumstantial needs, such as the Council for the South;

- Next, we find the control, accountability, and participation mechanisms alongside the relevant agreements, petitions, agendas, and all that falls under good governance (in today’s parlance);

- In terms of knowledge, a level that joins the national and international planes, Imam Sadr’s legacy is considered a major intellectual body of work. In addition to his scientific approach, reflected in consulting statistics and studies, assessing needs, and measuring the impact of projects, he had a rare magnetic presence and charisma. By harnessing his talent, skill, and learning, he was able to disseminate his experience and its outcomes at all intellectual and scientific levels, elite and popular alike;

- Finally, we arrive at the universal essence of his work, the pinnacle of the pyramid, by simply using a political lens to evaluate and gauge the value added by Imam Sadr to the human experience.

An observer may deduce, from all the aforementioned levels, what can be validly termed universal and merits to be tried elsewhere. To be extremely concise, we may say that his approach was to allow the people to determine their everyday needs and to empower them to meet these needs themselves. By people, he meant both men and women; a crucial addition for Middle-Eastern rural and urban communities. This participation generates self-esteem and self-confidence, which are essential conditions for trusting others, subsequently working together and enjoying advancement as an accomplishment. This progress allows, nay reinforces the values of participation, dialogue, and recognition of others, boosting the chances of peace and cooperation. This is true for family life and local endeavors, as well as for relationships between denominations, nations, and peoples. Sadr’s choice to make Lebanon proof of the validity of his thesis in attaining economic, social, and political justice remains a dream that will not be easily accomplished.

But the beauty of the dream lay in the enormity of the challenge.

ANNEX I: Selected Milestones

Below are selected milestones in Sadr’s path, each of which was later revealed as a guide, and deservedly so, for those striving for change for the better. Indeed, these are achievements and projects built on a comprehensive vision drawing on a deep analysis of the nature, causes, and catalysts of the problem. Wide-ranging and sophisticated conditions and reasons were complemented by interdependent solutions so that every stage built on the preceding one and laid down the foundation for the next:

- In light of existing studies and projects, it all started in the city of Tyre and its suburbs in 1961, with programs to support and aid the needy, launching literacy programs, creating public establishments, reinforcing the role of and empowering women by teaching them the arts of sewing, stitching, and homemaking, and offering first-aid training;

- In 1963, Imam Sadr proceeded to collaborate with the members of the Lebanese Forum (An-Nadwa Al-Lubnaniya) in a groundbreaking bid to engage dialogue between Muslims and Christians;

- In 1967, the Lebanese Parliament ratified the law on the institution of the Supreme Islamic Shiite Council based on the mandates set forth by Imam Sadr the previous year;

- Imam Sadr’s interests turned to affect deep change in women’s education and societal role. He created a kindergarten that he annexed to Al-Huda School. He also turned first-aid training into a higher technical school for nursing which is still operational today;

- In 1970, he founded the Committee for the Defense of the South and called for a nonviolent national-level strike which resulted in the creation of the Council for the South for the development of southern Lebanon and began the process of alleviating poverty in the country;

- In 1974, he founded the Movement for the Dispossessed (Harakat Al-Mahrumin) to raise awareness of the dire status quo and undertake serious institutional reforms, and continue meeting basic social needs through institutionalized action. The movement’s charter was signed by over a hundred and ninety intellectuals from all Lebanese denominations;

- In 1975, he founded the Lebanese Resistance Regiments (Amal) to defend South Lebanon;

- As of 1976, and over the two following years, he worked extensively towards ending the civil war which resulted in convening the Riyadh Conference and the Cairo Summit;

- In 1977, he presented the Shiite working paper on political and social reforms in Lebanon;

- On August 31, 1978, the world lost contact with Imam Sadr and his two companions, Sheikh Muhammad Yacub and Mr. Abbas Badr Eddine, on a visit to Libya, after having been officially invited by its ruler Colonel Khadafy, in a bid by Imam Sadr to contain the crisis in Lebanon in which the lybian ruler was involved through his support of specific factions.

ANNEX II: Projects and Institutional Structures

Social Issues and Healthcare

- He eradicated the phenomenon of street begging in Tyre by collecting donations to support the Charity Fund (Sunduq As-Sadaqah),

- He developed the internal regulations of Al-Birr Wal Ihsan charitable foundation in Tyre to promote the participation of women in public life and reinforce the offerings of the foundation on the whole,

- He established the Imam Al-Khoei orphanage for boys, and the Al-Zahra orphanage for girls,

- He founded Al-Zahra Hospital in Beirut’s western suburbs,

- He created Beit Al-Fatat home for girls in Tyre to care for, educate, and train girls in precarious situations,

- He established a welfare organization for males in Burj Shemali, Tyre.

Vocational, Education and Culture

- The Islamic Studies Institute in Tyre,

- Al-Zahra culture and vocational city in Beirut,

- Higher vocational school of nursing,

- The Islamic Association for Scientific Specialization

- Vocational institutions for boys and others for girls in Tyre, Beirut, and Baalbek, with the selection of marketable occupations for each area.

Economic Issues and Development

- He posed the challenges of agriculture and irrigation in Lebanon, based on studies developed by specialized international research teams, including IRFED* and FAO. He followed up on proposed projects to exploit river basins, especially Al-Asi River in Hermel, in eastern Lebanon, and Al-Litani River which flows from Baalbek to the East into Tyre in the South, as well as projects to construct dams, artificial lakes, and fully exploit surface water,

- He took into account available studies on oil and gas across the Lebanese coastline, following up on all developments pertaining to the matter, and raising the issue with the government,

- He studied available statistics on the socio-economic conditions in Lebanon’s underserved areas,

- He focused on regulating farming which constitutes a livelihood for the people of underserved areas in order to improve their living standards (e.g. tobacco farming in the South) and proposed a partnership between the State and farmers to guarantee the rights of laborers,

- He searched for alternative crops as a substitute to tobacco on condition they generate sufficient income to reduce migration,

- He created favorable conditions and opportunities to empower women to contribute to social and cultural development.

Emergencies and Relief

- Rapid response in providing housing, food, and basic needs, – Petitioning the State to allocate large tracts of land in the Hadath area of Beirut to build 260 housing units for those who were displaced at the time,

- Negotiating with a firm owning vast property in Ghobeiri (Beirut’s suburb) with the intent of buying the plot and build housing units to accommodate larger numbers of people if necessary.

Adopting the Approach of Partnership:

- He agreed with Bishop Gregoire Haddad within the framework of the Social Movement to handle the movement’s activities and projects in southern Lebanon,

- Took the initiative to allocate a tract of land for building a hospital, and then collaborated with Doctors without Borders “ Medecins Sans Frontieres” to manage the various specialties and equip the hospital.

Bibliography

i Noam Chomsky, Responsibility and War Guilt, conference interview, 25 June 2007, Znet

ii Islam, Universalism, and Relativism, www.onislam.net

iii Kurzman, Charles: Liberal Islam, Oxford University Press, 1998 (pp.5-9)

iv Observations and Reflections, lecture by Imam Sadr at An-Nadwa Al-Lubnaniya Foundation, 6/4/1964

v Excerpt from Lent sermon by Imam Sadr at the Capuchin Church – Beirut, 20/2/1975

vi Excerpt from Lent sermon, op. cit.

vii Islam and Human Dignity, lecture by Imam Sadr at the American University of Beirut, 8/2/1967

viii Only Freedom Preserves Freedom, Imam Sadr’s eulogy of late journalist Kamel Mruweh’s, delivered at Zrariyeh, 20/5/1966

ix Islam and Human Dignity, op. cit.

x Resistance, the System, and Shiism, interview, Kul Shai’ magazine, 30/6/1973

xi The South, the State, and the South’s Representatives, interview, Jamhuriya newspaper, 6/4/1970

xii The Imam’s Current and the Movement for the Dispossessed, interview, Anwar daily, 27/12/1976

xiii Islam and Human Dignity, op. cit.

xiv The Social Aspect of Islam, lecture by Imam Sadr at Dakar University, Senegal, 15/5/1967

xv Imam Musa Sadr, Nationalism and Patriotism, Muhammad Sammak, Al Mustaqbal daily, 5 September 2005, also refer to Al Mustaqbal, 1 September 2008 issue, and transcript of the NBN TV station interview with Sammak on 28 August 2003

xvi Orator and Beacon, Hussein Sharaf Eddine, Beirut

vii Rodger Shanahan, Transnational Links Amongst Lebanese Shi’a Clerical Families, Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies, Vol.1. No.3, p.311

xviii Excerpt from Imam Sadr’s message on Fitr, The Meaning of Eid, the Concept of Nation and the Resistance, 9/12/1069, published in Jaridah newspaper, 10/12/1969

xix The Meaning of Eid and the Concept of Nation, message of Imam Sadr on Fitr, 10/12/1969

xx Movement for the Dispossessed, Feudalism and Israel, interview, Anwar daily, 22/1/1975

xxi Daniel Buttry, Interfaith Heroes, p. 102, Michigan Roundtable for Diversity and Inclusion, 2008

xxii Lebanon and Human Civilization, interview with a delegation from the Syndicate of Press Editors at the Supreme Shiite Council, 17/1/1977

xxiii Lebanon and Human Civilization, interview with a delegation from the Syndicate of Press Editors, op. cit.

xxiv Foundations of National Dialogue, interview, An-Nahar, 31/1/1978

xxv Imam Sadr’s statement on the first anniversary of the civil war, published in An-Nahar newspaper on 17/4/1976

xxvi Statement of Imam Sadr following the meeting of the executive and legislative committees and the election of Imam Sadr to head the Supreme Shiite Islamic Council, Beirut, Dar Al-Ifta’ Al-Jaafari, 22/5/1969, published in Lebanese newspapers

xxvii Objectives and Organization, interview with Imam Sadr, Al-Hayat daily, 25/5/1969

xxviii A Model for Comprehensive Development, the Experience of Imam Sadr Foundation, Raed Charafeddine, statement at the Tenth Kalimat Sawa’ Conference: “Human Development: Religious, Social, and Intellectual Dimensions”, Beirut, 2005

Connecticut, March 5th, 2013

____________________________________________

Download pdf file: The Universalism of Imam Moussa Sadr-A Relevant Approach to Contemporary Uncertainty

Raed H. Charafeddine – First Vice-Governor, Banque du Liban

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 4 Sep 2017.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Universalism of Imam Moussa Sadr: A Relevant Approach to Contemporary Uncertainty, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: