Rohingya Crisis Ruled as Genocide by Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal

JUSTICE, 23 Oct 2017

Ali MC | Right Now/Human Rights in Australia – TRANSCEND Media Service

17 Oct 2017 – In September, the International Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal ruled the current Rohingya crisis as unequivocally genocide, denouncing the United Nation’s use of the term ethnic cleansing as a “euphemism” with “no basis in international law.”

After a week-long hearing at the University of Malaya, Judge Daniel Feierstein stated that the Myanmar Government was guilty of “war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide”.

War crimes listed included arbitrary arrest and torture; enforced disappearances; rape; killing; confiscation of property; and internal displacement.

The Tribunal also affirmed that the election of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy had only brought about an “acceleration” of human rights abuses, and in was an attempt to turn Myanmar into a “supreme Buddhist entity.”

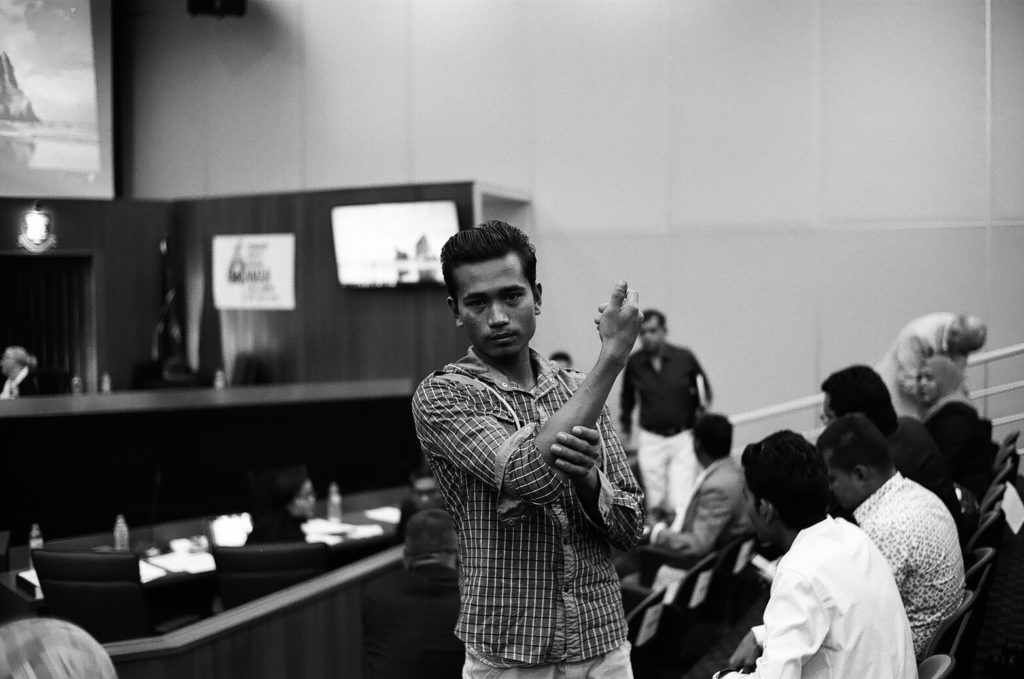

Throughout the week, expert witnesses and victims of human rights abuses testified to the Peoples’ Tribunal, which began a grassroots initiative in 1979 to denounce the crimes of Latin American dictators.

The Tribunal heard that ongoing human rights abuses have been committed not only against the Rohingya, but also other ethnic and religious minorities, including the Kachin people and other Muslim groups.

Testimonies included harrowing eye-witness accounts of mass rape of Rohingya women and the systemic slaughter of Rohingya men and boys.

This included the massacre at Tula Toli, a Rohingya village near the border of Myanmar and Bangladesh.

Mr Lazum Jimmy Phang provided evidence of the ongoing war crimes perpetrated against by Kachin people in the north of Myanmar.

Razia Sultana, a Rohingya lawyer based in Chittagong, showed video interviews conducted with women from Tula Toli. In the video, one Rohingya woman tearfully described the massacre, explaining that the villagers were told by authorities not to leave Tula Toli and that they would be safe.

Instead, she describes how the Myanmar Army descended by helicopter and surrounded the village. They then proceeded to systematically rape the women, killing and burning women, children and men.

“Nothing was left of the women … mutilated bodies were chopped up and set on fire … oh, there was a massacre in Tula Toli,” the woman exclaims.

Razia Sultana, a lawyer from Chittagong, gave harrowing first-hand witness accounts of Rohingya women who had experienced sexual violence.

Tactics, such as the promise of safety, were also used by Hutu militia in the Rwandan genocide of 1994, in order to herd Tutsi people into kill zones, such as churches.

In fact, parallels between the Rwandan genocide and the current crisis were noted during the Tribunal.

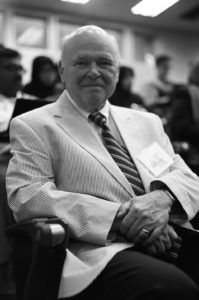

Founder and chairmen of Genocide Watch, Dr Gregory Stanton, explained a 10-stage process of genocide, which includes classification, such as the use of ID cards, dehumanisation, preparation and planning, and persecution.

A delegation of witnesses who provided testimony to attacks committed against Myanmar Muslims in other parts of the country, including the 2013 massacre in Meitkila.

This process, he said, amounted to genocide, which, under the Genocide Convention, is defined as “the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”.

Evidence of intent included a 1988 policy of the Myanmar Government to deny Rohingya citizenship, and that “any property must be confiscated and redistributed amongst the Buddhist population”.

Dr Stanton explained that the term ethnic cleansing was actually coined by former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, who faced charges of war crimes in 1999.

Unlike the Genocide Convention, there are no international legal instruments that address ethnic cleansing; as such, use of the term in the international sphere was said to be redundant.

Dr Gregory Stanton, founding president of Genocide Watch, gave a detailed account of the definition of genocide, and the difference between ethnic cleansing.

The Tribunal sessions were heavily guarded by Malaysian police, most notably due to the presence of outspoken Burmese activist Dr Maung Zarni.

Dr Zarni’s great Uncle was a collegiate of Aung San Suu Kyi’s father; he is related to many Burmese currently in positions of power.

Yet, due to his outspoken opposition to the regime, he has been labelled a traitor and an enemy of the state. Dr Zarni reported receiving death threats leading up to the proceedings.

However, in his testimony he stated, “I am not the enemy of the state; the state is the enemy of the people.”

The Tribunal concurred, describing how since the military coup in 1962, the government had been “at war with 40 per cent of its population.”

In line with the prosecution process, the Myanmar Government was invited to make a defence; however, it declined.

Instead, a video of Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent speech was played to the court.

In her speech, Aung San Suu Kyi said “We need to find out why this exodus [of Rohingya people] is happening.”

Had the Myanmar Government attended the proceedings, perhaps they would not be asking such an obvious question.

While the judgement passed down from the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal is not binding, it is the only official international entity currently defining the current crisis for what it is genocide.

The Tribunal also handed down seventeen recommendations to address the ongoing crisis, while Bangladesh government representatives announced they would be registering all new Rohingya refugees.

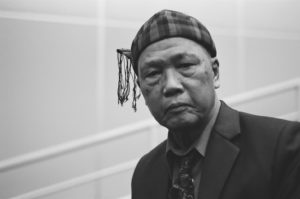

In his closing statements, the chair of the Malaysian Organizing Committee, Dr Chandra Muzaffar, repeated that oft-cited phrase “never again.”

Yet, without immediate intervention and sanctions from influential nations such as Australia – who’s Defence Force has been training with the Myanmar Army – genocide will continue to occur, yet again.

Read more about the Tribunal here.

_________________________________________________

Ali MC is a photographer, writer and musician and Human Rights Law Masters student. As well as traveling extensively overseas, he has also lived in remote Aboriginal communities teaching music and learning language. His first full-length book The Eyeball End was published in 2015, and in 2016 he produced a fourth album Urban Cleansing through his music collective New Dub City.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.