Operazione Colomba

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 28 May 2018

Nonviolent Peace Corps of the Association Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII – TRANSCEND Media Service

Descriptive Document on the Phenomenon of “Hakmarrja” and “Gjakmarrja”[i] to Raise Awareness among Albanian and International Institutions

Introduction

Operazione Colomba is the Nonviolent Peace Corps of the Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII Association. Civilian peace corps are made up of groups of civilians who go into armed conflict environments as third parties with the aim of protecting human rights and civilians, preventing dispute escalation, building confidence[ii] and creating nonviolent solutions to disputes using nonviolent instruments.

Since 1992 Operazione Colomba has been involved in nonviolent civilian peacekeeping, peace-making and peace-building in several armed conflict’s areas (e.g. the former Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone, Kosovo, East Timor (Indonesia), Chiapas (Mexico), North Uganda, etc.). Today, Operazione Colomba is working in Israel/Palestine (since 2002), Colombia (since 2009), Albania (since 2010) and in Lebanon alongside Syrian refugees (since 2013). This report is based on the work done by Operazione Colomba with the victims of blood feuds in northern Albania.

Since 2005 the contacts the Italian and Albanian workers of Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII Association have made with feuding families have enabled them to understand, monitor and report the practice of blood feud. Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII Association has asked Operazione Colomba to help produce a strategy for the nonviolent resolution of disputes triggered by blood feud situations.

Operazione Colomba has had a permanent physical presence in the Shkodra area since March 2010 and a monthly presence in the Tropoja area since October 2010. For over seven years its Italian and Albanian volunteers have been working to provide nonviolent ways of containing and resolving disputes arising from feuds between families.

Operazione Colomba’s main aim in Albania is to fight against blood feud and eradicate it. In order to achieve this aim, its volunteers conduct several activities: paths to help the members of feuding families overcome their anger and pain; paths to mediate between feuding families to achieve reconciliation; national awareness campaigns to ensure steps are taken to fight the practice and to create a general reconciliation process through restorative justice[iii]; monthly demonstrations in the areas most affected by the phenomenon to disseminate a nonviolent culture based on the respect of human rights; round tables and public meetings to involve Albanian associations and civil society in finding ways to solve the problem; dissemination of the words of people who have decided for reconciliation instead of vendetta; nonviolent accompaniments to ensure a greater freedom of movement and to enable people at risk of vendetta to access health care; networking with other associations working on the ground against vendetta to ensure the victims have access to education and recreation opportunities; monitoring and collection of data on the quantitative and geographic distribution of the phenomenon in order to develop a detailed and updated knowledge on the issue; the advertisement of the nonviolent actions undertaken. Operazione Colomba works with the people directly involved in feuds, with Albanian society, Albanian institutions and international institutions in general. Our volunteers meet feuding families on a daily basis. By living in close contact with them, our volunteers can share their difficulties, problems and risks to build up credible and trusting relationships.

- BLOOD FEUD – CAUSES AND CONTEXT

Albanian blood feuds were originally regulated by the Kanun, a Mediaeval codex used in tribal society. From the XIV century the Kanun was used to collect the many rules that regulated every aspect of Albanian life. Its basis is a symbolic universe governed by the concepts of honour (nderi), word of honour (besa), hospitality (mikpritja), virility (burrnija) and blood (gjaku). In Albanian culture, honour underpinned the relationship between the individual and the community to which he belonged. The protection of honour was essential to both the individual and the community because honour was the basis of social respectability. Defending your own honour and that of your clan, even at the cost of your own life, was a moral imperative. Any besmirching of the honour of a man or his clan could be revenged. Vendetta (hakmarrja) was a violent reaction to an injustice suffered but was not necessarily proportionate to the harm suffered. If vendetta took the form of murder, this could trigger a blood feud (gjakmarrja). The Albanian word gjakmarrja is made up of the words gjak, (blood) and marrja (taking) and literally means the taking of blood. Gjakmarrja could trigger a feud because it meant killing the murderer. Over the centuries the practice of gjakmarrja and therefore vendetta was extended to include the male relatives of the murderer. This produced long chains of killings between feuding clans. Killing a guest while he was under the protection of the owner of the house, violation of private property, failure to pay a debt, kidnapping or the seduction or rape of a woman were just some of the crimes that could trigger gjakmarrja.

Besa (word of honour) is a promise binding an agreement. It can have different meanings, depending on the context. Within the context of gjakmarrja, breaking your besa (word) could trigger a blood feud. A besa could also signal a truce in a blood feud. In this case the truce was a period of freedom and safety that could be of any length and that the victim’s family allowed to the killer and/or his family, temporarily suspending the vendetta. If the victim’s family refused to grant a truce, the killer and all his family then had to shut themselves in their homes as a sign of respect for the pain of the other side and to keep a low profile. According to the Kanun, the killer’s family must not appear proud or arrogant. The home was inviolable and therefore was a place of safety.

Mikpritja (hospitality) was sacred. According to the Kanun, an Albanian’s home belonged to God and his guests. Hospitality was therefore a moral duty. The Albanian home had to be ready to welcome guests at any time, offering bukë, kripë dhe zemër (bread, salt and an open heart). Welcome meant sharing meals, offering a bed for the night and the warmth of the fire. The head of the family had to offer the guest his protection, even if he was involved in a blood feud, so that when the guest left, the head of the house had to accompany him and ensure he was able to continue his road safely until the place required. The person offering hospitality was also required to declare a blood feud against anyone who insulted or harmed his visitor.

Burrnija comes from the word burrë (man) and signifies virility or ‘being a man’, i.e. a person who is virtuous and worthy of honour, who is dedicated to his clan and his family. Anyone who broke his promises, hospitality, agreements, truces or protection to guests was considered shburrnuem or i zhburrnuar (dishonoured or humiliated). Gjakmarrja was only between men over 15. Children under 15 and women were not involved in blood feuds.

Gjaku (blood) regulated relations inside and outside the tribe and therefore was an essential feature of the social structure. The importance of blood is typical of societies based on family ties. In feuds, the amount of blood spilt was the measure used to conduct the vendetta. In communities regulated by the Kanun, all males were equal. Male equality was essential to social relationships since at least in theory it prevented injustice being applied by men in a privileged social position. Gjakmarrja was therefore based on a ‘head for a head’ (një kokë për një kokë) or ‘blood for blood’ (gjak për gjak) – a variation of the law of retaliation.

Blood also symbolises brotherhood. In the face of dishonour, vendetta was not the only solution offered by the Kanun. A dishonoured man could also choose to forgive the clan that had dishonoured him. The Kanun of Lek Dukagjini states that “dishonour cannot be revenged through compensation but by the shedding of blood or generous forgiveness[iv]” (falja). Forgiveness was burrnor, i.e. an honourable and courageous choice. The potential for peace offered by the Kanun lies in the besa and reconciliation, which can be achieved through mediation. Mediators are community and/or religious figures whose moral authority enables them to lead the mediation, influencing the views and behaviour of the feuding parties.

If feuding clans decide to forgive an offence, a reconciliation ceremony (pajtimi) is celebrated at the end of the mediation process. Participants in the ceremony used to drink a drop of each other’s blood mixed with the local spirits (raki) or water, linking arms as they drank. Drinking each other’s blood meant that their families and descendants became related to each other.

Blood feud (gjakmarrja), forgiveness and reconciliation (falja and pajtimi) formed a justice system that met the need to regulate relations between native people and families in areas where the Turks were unable to impose their own government. In this type of society, the injured party declared vendetta as punishment for what it had suffered and to act as a deterrent against criminal actions. In this sense, vendetta can be seen as a method used in the past to restore and maintain public order in a society in which the State had no authority.

During the period of Ottoman domination (XV-XIX centuries), the Kanun was respected and applied especially in the mountainous areas of the country and formed the basis of traditional local culture. All the rules in the code, including those on gjakmarrja, were practiced in different ways depending on social context and historical circumstances. There were a number of different forms of the Kanun: of Lek Dukagjini[v], of Mirdita, of Puka, of Luma, of Çermenik, of Benda, which were used in the north; the Kanun of Labëria used in the south; and the Kanun of Skanderbeg[vi] or Kanun of Arbëria used in the centre-north. This was a traditional, flexible law subject to constant change.

At the start of the XX century and despite Istanbul’s tighter control over the north of Albania, the communities in that area continued to govern themselves using the tribal system. Strict Turkish policy encouraged already existing rebellion and in 1912 Albania became independent. In the years that followed, the new Albanian State created laws, a civil and criminal code and a central government to challenge the organisation of society in the mountains. In the north of the country in particular the clans did not in practice accept the laws of the new State and remained faithful to the Kanun. Blood feuds remained common and could involve entire village communities. It was only during the Italian Fascist occupation of Albania (1939-1943) that vendetta became less frequent. The Italian invasion focused local populations on resisting the foreigner and blood feud tended to give way to reconciliation as a way of ending disputes.

Between 1946 and 1991 Albania had a Communist government that became increasingly totalitarian and repressive before becoming a dictatorship. By gathering all power into his own hands and those of the Party of Labour, of which he was Secretary, Enver Hoxha governed Albania for around forty years until his death in 1985. The country was modernised through industrialisation and the nationalisation of companies. Private property was abolished and replaced by enforced collectivisation of the land. Hoxha restricted the freedom of worship and in 1967 imposed the atheist State. The Party of Labour aimed to dismantle traditional values and replace them with a National-Communist ideology. The mountain code, which had for centuries underpinned the ethics of the populations in the north of Albania, prevented the embedding of modernisation values and challenged the claims that Hoxha’s Communist ideology was indisputable and absolute. The Kanun recognised and allowed private property, unlike the Party of Labour with its collectivisation of the land. The code challenged the atheist State with its clear ecclesiastical and Christian references. The Party of Labour’s policy was therefore to abolish the morality enshrined in the Code. The regime imposed severe punishment on those who followed the Kanun. In the Communist period gjakmarrja in Albania fell significantly. But even though there were fewer instances of gjakmarrja, the principles by which village communities in the north of Albania were regulated remained in place.

When Communism fell, the country found itself in a precarious and uncertain position. Investment in economic recovery was insufficient and basic services were not guaranteed. In 1997 the attempts at economic recovery ended in dramatic collapse. The government had used Ponzi scheme to set up pyramid-shaped companies that operated like banks, whose customers were encouraged to invest in them with promises of high interest rates that would grow their savings fast. This created a financial bubble that eventually burst, carrying with it the assets of the investors. Poverty fell to even deeper depths than before and the country went bankrupt. The population reacted by attacking the government’s weapons depots in an attempt to take back what they had lost, and civil war broke out.

The precarious situation and power vacuum created with the collapse of Communism led to the return of gjakmarrja as a traditional value to replace crumbling modernisation values. Gjakmarrja resurged in yet another State vacuum. While blood feud to some extent continued to regulate public order in the absence of an effective justice system, it also acquired new meaning. Blood feud was no longer just a means of resolving disputes. In a completely different environment from that in which it had originated, the meaning of the blood feud began to change and its purpose to expand. Gjakmarrja now started to be used in another way to suit the current situation. The causes of the bastardised form of blood feud include:

– Factors inherited from Albania’s recent past. The abolition of the agricultural co-operatives and collectivisation led to a fight to re-establish private property. The land was redistributed. In the north of the country privatisation encountered serious difficulty. Collectivisation had arrived ten, sometimes twenty, years later than in the rest of Albania so that in the 1990s the memory of the division of land before the agricultural co-operatives was still strong. Furthermore, the land was reassigned free of charge to the farmers who held it and not to its owners. This meant that some families were living on farms on land owned by other people. The result was an explosion in disputes.

- Institutional vacuum. Albania’s political institutions have struggled to emerge from the heavy inherited trappings of the Communist regime. In the 1990s the instability of the State and its laws led to weak institutions and high levels of corruption in the public administration. Corruption in the legal system was one of the main causes of the rise in vendetta. If members of the most economically powerful and prestigious clans could afford legal treatment different from that meted out to other people, then the law was not the same for everyone. Since the serving of sentences for honour offences or vendetta could not be relied on, general uncertainty and distrust in the State grew. In many cases, gjakmarrja became synonymous with private justice when State justice failed. Corruption also created another problem. The democratic principles underpinning State laws became meaningless when the law was not applied or was applied only on a personal basis.

Communities may reject democratic values if in practice they mean corruption. However, the social need for fixed values remains and it was for this reason that the values of the past returned to the fore. If the law is not the same for everyone, the indigenous people may prefer and therefore legitimise the law of revenge if it appears to ensure equal treatment for all. As a result, DIY justice became an alternative to the State justice system.

- Low level of education. This has led to inadequate and insufficient education in respect for the rules of democracy, particularly in the new suburban communities where inhabitants can no longer apply rules of social control used in their traditional places of origin and they find it hard to adapt quickly to the rules of a State that is marching towards full democracy. A study by the People’s Advocate on murders committed for blood feud’s reasons from 1990 to 2012 shows that 39% of the killings were by people with little or no education[vii].

- In the 1990s the Albanian population moved from the mountains into the towns and suburban areas, spreading traditional mountain ways of thinking.

- Current social culture. In the 1990s weak economic development, internal migration from mountain areas to the suburbs and low education levels in rural areas in many cases created the conditions for maintaining a culture based on family, patriarchy and male chauvinism. In some areas of Albania the traditional way of thinking was also preserved through the arranged marriage of couples from mountain backgrounds. This led to clan culture behaviours, where the family is the nucleus of the patriarchal community and therefore its blood ties, personal freedom to make decisions is based on that of the family, life is not always the most important social value, personal expression is restricted to each person’s personal domestic role and social pressure determines the behaviour of the individual and the clan to which he belongs.

- This factor is connected with the isolation that is still a feature of some areas. The impenetrability of some mountain areas means that life in the mountains in the north of Albania remains hard and that traditions remain strong and resistant to the assimilation of other ideas.

Seen from the inside, vendetta is a contradiction in the neither entirely modern nor entirely traditional society of Albania today. It occurs against a background of developing civil and political awareness, where social movements to defend particular rights are still fragmentary and education in human rights is needed in primary and secondary schools.

Seen from the outside, vendetta is preventing the country joining the European Union because it is a violation of basic human rights. One of the conditions for Albania joining the EU is the rooting out of the practice. The EU does not allow private systems of justice. Vendetta also creates public order problems, not just domestically but internationally too since a number of cases of gjakmarrje and hakmarrje have occurred outside Albania (see section 3 below).

- FEATURES, DYNAMICS AND CONSEQUENCES OF BLOOD FEUD[viii]

In the last twenty years traditional vendetta has been a response to need felt in the new environment in which it occurs. On the one hand, institutional gaps must be filled and the resulting mistrust combatted, and on the other, action must be taken to deal with the new global capitalism model and its values. Domestic migration from mountain areas to city suburbs has also raised the question of how these flows should be managed and the way they have embedded in urban and suburban areas. As we have seen, the inhabitants of mountain communities still have a background based on the Kanun tradition. While this may have enabled mountain peoples to maintain their identities when they moved to places where integration was difficult, it has made their lives hard. Some of the needs currently felt by these populations are similar to those of the past but occur in completely different contexts and therefore take different forms. Traditional rules are consequently not being applied as set out in the Kanun of Lek Dukagjini and are creating new situations. Gjakmarrja is one example of this. Vendetta is no longer practiced according to the code and has become more complex. The memory of the Kanun is now in practice under constant change, partly because many feuding families have no direct knowledge of it. Culturally, the practice of vendetta is moving away from tradition to develop new forms that, because they arise from new situations, no longer have any connection with the traditional code since they are creating new socio-cultural meanings for gjakmarrja. The following examples show how blood feud has changed in practice.

Firstly, in the oldest version of the Albanian mountain code the murderer alone was subject to vendetta. This has changed over time. Gjakmarrje feuds now rarely kill the murderer and it is more frequently his male relatives who are targeted.

Secondly, the Kanun of Lek Dukagjini excludes religious authorities, women and children under 15 from gjakmarrja. In the last few years, women, children and religious authorities have been the victims of blood feud violence. On 8 October 2010, a Protestant pastor was killed in a vendetta involving a branch of his family. In Dukagjin in June 2012, a 17-year old girl was murdered in a feud between the clan to which her family of origin belonged and another (Shqip, 15.06.2012; Shqip, 20.06.2012; Shekulli, Panorama, Gazeta Shqiptare, 16.06.2012; Gazeta Shqiptare, 19.06.2012). In April 2013 an 18-year old girl was killed in the mountain village of Tropoja during a property dispute between her father and his cousin (Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, 27.04.2013).

The Kanun of Lek Dukagjini states that manslaughter must not be revenged with weapons. In the last few years blood feuds have involved people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. One example is the murder of 9-year old Endri Llani on 5 May 2012 in Mamurras. He was hit ‘by mistake’ by a bullet aimed at his 22-year old uncle during a fight with another man. Around two months later the child’s father revenged the death by killing a 71-year old man who had been involved in the child’s murder (Shqip, Gazeta Shqiptare, 06.06.2012).

Thirdly, the oldest members of the feuding clan or family used to decide how the clan should act towards the other side, but now decisions to take revenge are also being made by young male members of the family.

Abuse of the Kanun has also led to misuse of the practice of self-confinement (ngujimi[ix]) by the killer in his own home. According to the Kanun of Lek Dukagjini, ngujimi did not apply to the killer’s family unless the victim’s family did not agree to a truce with them. Today, self-confinement often includes the killer’s family. The member of the killer’s clan tend to move from the place where the murder was committed to another place, or abroad. This however is not always enough to reduce the tension between the parties or ensure the safety of those involved. Clear and implied threats that may be real or assumed through fear of vendetta will lead the members of the clan guilty of the crime to shut themselves in their homes and live in fear. The most vulnerable members of families at risk of vendetta end up living isolated from the rest of the world. People who live in self confinement lose their jobs and the ability to look after their families. In the last few years there have been cases of children, girls and women who are relatives of a killer remaining “nailed up” in their own homes. Albanian public opinion now often equates blood feud with self-confinement, but this interpretation does not help understand the breadth and extent of the practice.

The misuse of tradition has created a mentality that has given rise to and worsened current disputes. Blood feud disputes are classified as micro-disputes that by also involving the relatives of the parties in the dispute degenerate into meso-disputes. Disputes that initially involve just a few individuals end by involving their families. And the involvement of the families can in turn lead to the involvement of the entire clan. Because of the tradition from which the practice has developed, blood feuds are still strongly associated with the concepts of blood and honour. Blood ties determine the relations on which the family is built and the members of that family. By tradition, blood ties are transmitted down the male line alone, and although honourable and dishonourable acts can concern both men and women, men must carry them out in accordance with the decisions of the family members. At present vendetta affects mainly men. Honour however regulates social relationships and is an expression of the respect an individual earns from society through honourable actions. The weight of such actions has a direct impact on the respect given to the family to which the individual belongs through blood ties and it is in this way that the family and the clan to which he belongs gains honour. These principles determine the attitudes and conduct of individuals and the families to which they belong. Recovering honour is essential to regain respect within the community.

Most blood feuds occur in places where living conditions are precarious. They occur mainly in suburban and mountain areas where unemployment and poverty is great, there are few basic public services, and certain social attitudes, such as patriarchy and male chauvinism, are strong. But blood feud mentality is not typical of just the most isolated areas. Since most city inhabitants come from rural areas, it is hard to find Albanians born in one of the country’s big cities. The Albanian melting pot has therefore produced such a mixture of mentalities that it is difficult to say that Kanun thinking does not also exist in urban areas today.

Furthermore, since the code has Christian origins, blood feuds mainly affect Christian families. The north of the country remains the area in which the practice is most deeply rooted because this is where most of the Christian and Catholic population lives. Yet vendetta is also a trans-religion practice and can affect any Albanian family. It therefore ignores religion but affects all religions practised in the country.

The reason lies in the two practices of the past (hakmarrja and gjakmarrja) that because of the misuse of tradition now occur in bastardised form. While the victims of the practices continue to use the old names to create a link with their symbolic roots, some academics are beginning to wonder whether the same names should continue to be applied to practices that are moving away from their original uses.

The following examples are typical of blood feud disputes.

– Gjakmarrje:

- 14 February 2013 in a village near Peshkopi, Hike Skuka, wife of Uran Skuka, and Xhemile Skuka, wife of Edmond Skuka (Uran and Edmond Skuka are brothers), killed 67-year old Naime Skuka (mother of Uran and Edmond Skuka) because of the abuse they had suffered at her hands, by pouring boiling oil in her ear. 13 February 2014, Uran Skuka killed Basri Nikolli, the brother of his ex-wife, to revenge the murder of his mother (Gazeta Shqiptare, 20.07.2014; Panorama, Gazeta Shqiptare, Shekulli, 10.08.2014). In 2014 Uran Skuka was given a 35-year prison sentence for “murder by gjakmarrje and unlawful possession of weapons of war” (Panorama, 7.10.2014).

CLAN NIKOLLI VS. CLAN SKUKA

Hike Skuka (ex-clan Nikolli) and Xhamile Skuka —– killed in hakmarrje ——-> Naime Skuka, mother of Uran and Edmond, the husbands of Hike and Xhamile

AFTER 1 YEAR

Uran Skuka —- killed in gjakmarrje ——> Basri Nikolli, brother of his ex-wife Hike

- In 1991 Lulzim Shera killed his cell mate, Arjan Baku, in a fight while serving a sentence for instigating the suicide of a girl. After the murder his sentence was increased to 20 years. On 1 September 2013, more than one year after he was released from prison and more than twenty years after the murder, Altin and Skënder Baku, the brothers of Arjan, implemented gjakmarrja and killed43-year old Lulzim Shera, the murderer of their brother, in Fushë-Kruja, even though he had just served 20 years for the crime.

CLAN SHERA VS. CLAN BAKU

Lulzim Shera —– killed in hakmarrje ——-> Arjan Baku, brother of Altin and Skënder Baku

AFTER 22 YEARS

Altin Baku, Skënder Baku —- killed in gjakmarrje ——> Lulzim Shera Gjakmarrje can lead to vendetta cycles that gradually kill off the members of the feuding families and endanger the lives of all the relatives of the person who besmirched the other party’s honour. Gjakmarrje feuds are consequently not easy to resolve. In this case (clan Shera vs. clan Baku) we see, for example, that even the serving of a criminal sentence is not always enough to prevent a blood feud. Since the practice is the product of a particular way of thinking, it needs to be fought not just through reform of the justice system but also culturally (see section 1 above).

– Hakmarrje:

- 11 July 2015, Abaz Isa (age 54) killed Pastor Marjo Laho (age 26) in the Gramoz mountains in a feud apparently over the ownership of some meadows but that later was found to be about the beating by Marjo Laho of Abaz Isa because that latter had previously beaten the victim’s father (Panorama, Shekulli, Gazeta Shqiptare, 13.07.2015; Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, Shekulli, 15.07.2015; Shekulli, Shqip, 20.07.2015).

CLAN LAHO VS. CLAN ISA

Abaz Isa —– killed in hakmarrje ——-> Marjo Laho

- Tom Lala (age 69) killed Mark Ndreca (age 50), his cousin, in a village in Kurbin on 2 April 2016 in a dispute over property. Shortly after the murder, the killer’s family shut itself in its home for fear of a blood feud against it. To prevent this, the police monitored the area for some days (Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, 3.04.16; Panorama, 4.04.16, 5.04.16, 6.04.16; Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, 07.04.16; Gazeta Shqiptare, 09.04.16; Panorama, 10.04.2016; Panorama, Gazeta Shqiptare, 24.06.2016).

CLAN NDRECA VS. CLAN LALA

Tom Lala —– killed in hakmarrje ——-→ Mark Ndreca

Hakmarrje can degenerate into vendetta and thus into feud.

The main causes of blood feud are:

– disputes over property. Historical factors (past processes and events underlying the current distribution of property in the community) are crucial to the reopening of some disputes (see section 1). On 12 August 2015 in a village in Kukës, six men from different clans almost killed each other over a dispute concerning the ownership of a stream (Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, 13.08.2015).

– Human trafficking. Human trafficking mainly concerns women and prostitution. Organised crime uses the Kanun to legitimise female subordination. In other cases the code is used to maintain internal order, ignoring the positive aspects of the tradition, such as peace-making and hospitality. Vendetta is thus used by organised crime as a way of settling accounts in illegal trafficking, e.g. of contraband.

– Honour. This gives rise to disputes for petty reasons. In July 2015 in Greece a 21-year old man was tortured and killed and his body burned by a jealous husband who suspected him of having an affair with his wife. All involved were Albanian. Disputes over honour can have petty reasons, such as physical or verbal provocation, envy and jealousy or quarrels at a bar after one raki too many. On 11 May 2015 the mayor of a district in the municipality of Has in Kukës shot two people after a fight for petty reasons, made worse by having drunk one too many (Gazeta Shqiptare, Shqip, 12.05.2015).

– Car accidents. On 23 August 2012 a man was injured by a firearm when he was in his car with his

girlfriend. The police investigation assumed that this was an act of vendetta over a previous car accident in which the victim killed a member of the road police (Panorama, 19.11.2012).

– Debt. On 11 August 2015 in a small municipality in Tirana a 19-year old seriously injured a 27-year old man over a 100 euro debt (Panorama, 15.08.2015).

– Work. On 4 October 2013 a 47-year old man from Shkodra was killed over work-related problems. The main suspects were his colleagues (Panorama, Shqip, 4.10.2013).

– Fear of vendetta for offences caused, which drives the culprits to attack first. In these cases, inability to control emotion can degenerate into murder.

Factors in deciding on vendetta include: inability to manage emotions constructively and social pressure.

The first is found when emotions such as anger and bitterness lead to reactions that end in murder.

Over time these emotions can turn into hate and lead to vendetta.

The second factor is caused by the influence that the social environment in which the victim’s family lives (neighbours, relations, school and/or work mates, etc.) has on clan decisions. Since in the current cultural environment vendetta is more common than forgiveness and reconciliation – both of which options tradition permits – social pressure is negative since it can affect the decision to seek revenge. Occasionally when dishonour occurs it is the most distant relatives or those living abroad, who are not directly bereaved but who feel that the family’s honour has been besmirched, who exert the negative influence on the victims’ decisions. If the direct victim of dishonour lives in an environment that causes him to turn the suffering he feels into hate and rancour, the desire for vendetta can translate into action.

The escalation of feuds turns such cases into spirals of vendetta that influence feud dynamics.

The main aspects of these dynamics are:

- Type of vendetta. The actions of both sides can become increasingly savage. The type of vendetta and its effects tend not to reflect the dishonour suffered. Rebecca Basso, the director, describes one of the disputes she discovered while filming the documentary “Kanun, il sangue e l’onore”[x]. In one case a fight broke out in a café when a group of friends started quarrelling. In a fit of anger, one of the men pulled out a gun and killed another. In addition, gjakmarrja when the other person is celebrating a happy occasion, such as a wedding or a christening, ruins the happiness of the other family and therefore causes greater emotional damage than a vendetta that occurs in normal circumstances.

- Increasing hostilities lead to the involvement of ever larger numbers of people. In some cases the killer has shot more victims than expected during the vendetta. In 2012 an under-age boy tried to revenge the death of one of his relatives but while the burst of gunshots only injured his target, it caused two casual victims: a boy who was also injured and a young man who was killed in the attack (Gazeta Shqiptare, Shekulli, 23.11.2012; Gazeta Shqiptare, Shqip, Koha Jone, Panorama,

21.11.2012; Panorama, 22.11.2012). This triggered a new feud between the family of the under-age boy and that of the boy who had been killed.

- These examples of gjakmarrje and hakmarrje show how vendetta incubation times can differ significantly. It can either explode very fast or several years after the injury or first murder. Although feud stories tend to be passed down, the reason for their origin can be forgotten as time passes.

- At a time when institutions are struggling to enforce the law, vendetta is being used as a private form of justice (see section 1). In addition, the Albanian population has still not entirely absorbed what ‘public’ means. Citizens’ pursuance of their own private interests therefore often falls outside the law of the State. Both of these factors assist in the modern implementation of Kanun tradition.

- The lack of collaboration and the code of silence practised by the local population do not help the police with their investigations. Silence for reasons of self-interest, or more usually for fear of reprisals, slows the course of justice and prevents the reporting of vendettas.

To comprehend the effects and consequences of vendetta, the way in which it totally conditions the lives of those involved must be understood. Insecurity and fear for life increase not only for those involved but also for Albanian society as a whole. The carelessness with which some examples of hakmarrje and gjakmarrje occur can be felt to indicate that anyone could potentially be involved.

Vendetta also affects the emotions of the individual and families. Members of families related to a murderer fear being threatened and killed. Self-confinement causes frustration and depression that destroy the personalities of those involved. Once a family “falls in blood” with another family, the daily life of each involved family member is interrupted and controlled by the vendetta. In some cases parents keep young people and children home from school for fear that something might happen to them. From a very early age, boys are considered and treated as small men within the home. The stages of childhood that contribute to balanced growth are destroyed. Vendetta therefore affects the formation and growth of the individual, as well as personal and social relations in community life. Men who used to go to work stop doing so and withdraw into their homes. Self-confinement often leads to male alcoholism and increased domestic violence. Women bear the brunt of such situations because the burden of looking after the home, educating the children and maintaining the family financially can fall on their shoulders.

And families who have suffered bereavement because of a blood feud feel anger, which can grow if there is no certainty that the murderer will be punished. The destructive power of this feeling transforms it into rancour and then hate can be transmitted to all members of the clan to which the victim belonged: the young, the adults and the old. The stories of what happened can be repeated to keep the memory of the offence alive. All these factors can influence a decision for vendetta.

The main problems are: psychological harm (e.g. persecution mania, depression, neurosis, alcoholism, etc. which often translate into domestic violence) caused by the suspicious, closed, fearful environment marked by death and violence in which the people involved live and grow up; physical harm caused by lack of freedom of movement and therefore the inability to obtain medical care or by the results of violence; increased rate of illiteracy; financial harm caused by unemployment; the spread of disputes and violence caused by exclusion and isolation.

Blood feuds therefore seriously violate fundamental human rights, the most important of which are:

– the right of equality, because those involved in feuds often suffer social exclusion;

– the right to life, freedom and safety, which is violated by hakmarrje, gjakmarrje and self-confinement;

– equality before the law, a right that is violated if punishment is not certain;

– the right to privacy, which is violated whenever authorities or the media make improper use of the personal data of those involved in a vendetta;

– the right to work and education, because those involved in feuds often lose access to education and work;

– the right of asylum. Requests for international protection abroad are mainly because of vendetta, domestic violence, discrimination against minorities, human trafficking and financial and health problems. The 2014 data of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) show that 43% of asylum requests in Belgium and 40% of those in France were the result of vendetta. It is not always easy to ascertain whether applicants are truly caught up in a vendetta. In some cases there is a real need to leave Albania for this reason but since murders and injuries are not reported or recorded, requests can be rejected for lack of proof. In other cases, the need to emigrate is caused by poor living conditions, which the applicant conceals by submitting fake certificates showing that he/she is involved in a vendetta in order to increase the likelihood of asylum. This has tightened European international protection procedures, to the detriment of those who truly are the victims of a vendetta.

This is therefore a fragmented situation that continues to change as it moves away from tradition to become a hybrid phenomenon that concerns different places such as villages and towns. In this sense, hybridisation is based on a power relationship between the city and the suburbs and can develop either as the suburbs adopt the standards of the city or as the city is destabilised by the suburbs. This form of hybridisation is producing standards and practices that, as in the case of northern Albania, are the result of bastardised tradition.

- GEOGRAPHIC AND NUMERICAL DISTRIBUTION OF BLOOD FEUDS

Data on the geographic and numeric distribution of blood feuds varies considerably, depending on source.

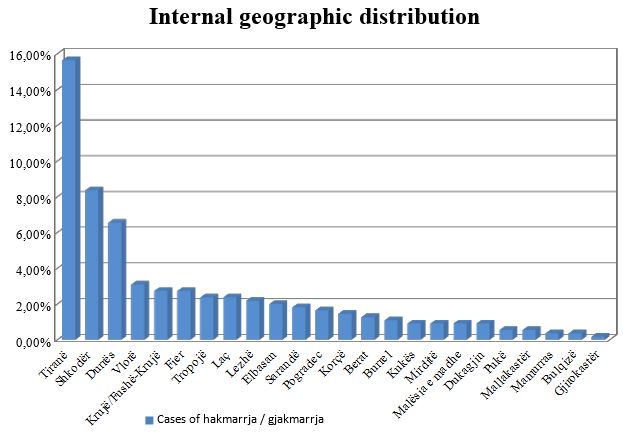

In terms of geographic distribution, most disputes occur in the suburbs of the big cities in the north and centre of the country, as Operazione Colomba research since 2010 has found. Since 2011 Operazione Colomba has been monitoring the cases of hakmarrja and gjakmarrja reported in the Albanian and international media, especially since 2013. The resulting database relies on the following dailies: Panorama, Shekulli and Gazeta Shqiptare, supplemented by other national publications such as Shqip and Mapo and occasional news reported in the international press and online media. However, the data given in the articles we have examined also provides information on older cases that go back to the 1980s.

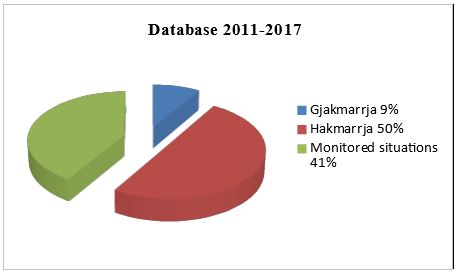

At December 2017 the Operazione Colomba database included 550 cases of injury, attempted murder and murder caused by hakmarrja or gjakmarrja. Some articles specifically refer to blood feuds, while others have been classified as such by Operazione Colomba staff based on the information they contain and typical motives for blood feud. Yet other cases are still being monitored to check future developments.

Of the 550 cases in the database, 48 are believed to be caused by gjakmarrja and 275 by hakmarrja. Some blood feuds are the result of previous hakmarrja that has degenerated into one or more cycles of gjakmarrja. The other cases are being monitored for possible eruption into blood feud. Compared with Operazione Colomba’s 2014 statistics, over the three years of the new period examined (January 2015 to December 2017) there have been 141 new cases of hakmarrja and 15 new cases of gjakmarrja.

The database shows that most causes of hakmarrja and gjakmarrja are connected with property, previous disputes or honour. These are followed by other reasons such as: petty reasons, verbal provocation, settling of accounts, debt, work problems and fear of vendetta for an offence that causes the culprits to attack first.

The cities with the largest number of hakmarrja and gjakmarrja events are (in decreasing order): Tirana (86), Shkodra (46), Durrës (36), Vlora (17) and Lezhë (12). These are followed by: the region of Kruja/Fushë-Kruja, Fier, Tropoja and Laç, Elbasan, Berat, Pogradec, Dibër, Malësi e Madhe, Lushnjë, Saranda, Puka, Tepelenë, Kukës, Mirdita, Gjirokastër, Dukagjin and Korçë.

In addition to blood feud within Albania, we are also unfortunately seeing the export of vendetta, where some cases are continued even outside the country. According to Operazione Colomba’s database, since 2013 a number of blood feud murders were committed in the following countries: 11 in Italy, 4 in Greece, 2 in Belgium, 2 in France, 2 in Germany and 2 in the Netherlands. These are followed by 1 in Kosovo, 1 in Montenegro, 1 in the UK, 1 in the Czech Republic, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Switzerland, 1 in Canada and 1 in the USA.

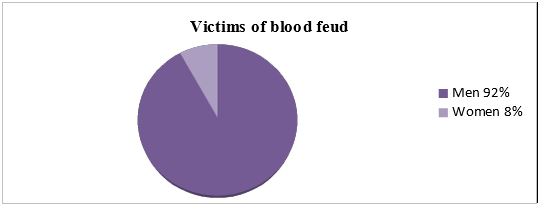

The age of victims varies widely between 9 and 91 but most are between 20 and 60.

The vast majority of victims are men (508 cases out of 550) but the number of women is also not small (42 cases out of 550). Women are included not only for the above reasons but also because of domestic violence (see section 2).

This is a constantly growing, not decreasing, phenomenon that is generalised from many viewpoints because it concerns many places across Albania and is spreading abroad as the Albanian nationals caught up in it move outside the country, and it affects people of all ages and both sexes and wide periods of time up to the present day.

Examination has shown that the dynamic of the phenomenon means that it is moving ever further from the original rules set out in the Kanun and is increasingly able to adapt to the needs felt in each new situation.

The data available varies considerably, depending on the source. There are three types of source: Albanian institutions; Albanian and international associations on the ground; and international organisations. Data published by any one of these sources is often used by the others. Information collected from these bodies consequently often overlaps.

Albanian institutional sources include the Advocate of the People and the Government of the Republic of Albania. Data collected by the Advocate of the People between 1990 and 2012 mentions 6000 deaths caused by gjakmarrje.

Government data 1991-1995 mentions 953 murders, of which 9.5% caused by hakmarrje or gjakmarrje. In 1997 alone, the Albanian Police identified 1542 murders and 2910 families injured or involved in hakmarrje or gjakmarrje[xi].

In 2012 the Interior Ministry issued the first official estimates of gjakmarrja. These showed 225 murders resulting from gjakmarrje over 12 years (1998 to 2012[xii]). Interior Ministry statistics show that the 225 murders represent 7.9% of all crimes committed.

The following shows the partial numeric distribution of murders caused by gjakmarrje from 1998 onwards, based on Interior Ministry data. Comparison with annual percentages is interesting. According to this data, the progress of the phenomenon is not constant and appears to be slowing.

Table No. 1

| Years | No. Murders | No. Gjakmarrja murders | Percentages % |

| 1998 | 573 | 45 | 7.8% |

| 1999 | 496 | 41 | 8.2% |

| 2000 | 275 | 41 | 14.9% |

| 2001 | 208 | 32 | 15.3% |

| 2003 | 132 | 12 | 9% |

| 2004 | 190 | 11 | 5.7% |

| 2005 | 131 | 5 | 3.8% |

| 2006 | 87 | 4 | 4.5% |

| 2007 | 103 | 0 | 0% |

| 2008 | 88 | 5 | 5.6% |

| 2009 | 82 | 1 | 1.2% |

| 2011 | 135 | 5 | 3.7% |

| 2012 | 100 | 5 | 5% |

The information provided by Albanian and international associations on the ground includes data from the Tirana Nationwide Reconciliation Committee, the Shkodra Dukagjini Association[xiii], the Shkodra Justice and Peace Commission and Operazione Colomba. The 2014 Operazione Colomba report also covers examination of 180 examples of dispute, injury and murder in 276 articles in the main local newspapers (Gazeta Shqiptare, Panorama, Shekulli) between August 2011 and September 2014. 134 cases of hakmarrja and 33 of gjakmarrja have been identified.

Table No. 2

| Association | Year | Area | Vendetta murders |

| Committee of Nationwide Reconciliation | From 1991 to 2009 | North, Center and Southern of Albania | 9800 |

| Association “Dukagjin” | From 1991 | Dukagjin | 144 |

| Justice and Peace Commission | From 1990 to 2008 | Shkodër, Malësia e Madhe | 165 |

| Operazione Colomba | From 1999 to 2015 | Tropojë,Dukagjin,

Malësi e Madhe, Mirditë,Elbasan, Vlorë,Berat, Pogradec,Fier,Dibër, Lushnjë, Sarandë, Pukë,Tepelenë,Kukës, Gjirokastër, Korça |

204 |

The international organisations include the OSCE that provides data supplied by the Justice Ministry in 2007, the Shkodra Justice and Peace Commission in 2010, the Advocate of the People in 2013, the Tirana Nationwide Reconciliation Committee 2013-2014, Shkodra religious institutions in 2014, the Children’s Rights Centre of Albania in 2013[xiv] and the Shkodra public prosecutor in 2014.

Table No. 3

| People charged with vendetta | Families in self-confinement | Adults in self-confinement | Children in self-confinement | Families in ‘blood’ | Year/s | |

| Justice Ministry | 13 | 2007 | ||||

| Justice and Peace Commission | 138 | 120 | 2010 | |||

| People’s Advocate | 5 | 67 | 154 (in 2012) | 33 | 1559 | 2013 |

| Committee of Nationwide Reconciliation | 980 | 306 | 4900 | 2013/2014 | ||

| Religious In stitutions in Shkodra | 138 | 15 | 238 | 2014 | ||

| Children’s Rights Center of Albania | 2013 | |||||

| Shkodra Prosecutor | 36 | 196 | 2014 |

In August 2015 Civil Rights Defenders, an international organisation, published a report on Albania that referred to blood feuding and to the fact that at least 70 families were living in self-confinement[xv]. There is clear discrepancy among the data. While some government officials maintain that NGO data has been exaggerated to support requests for urgent action from the Albanian authorities, the independent organisations accuse the Albanian authorities of underestimating the phenomenon for fear that this might slow down membership of the European Union.

The cases that have been directly monitored by Operazione Colomba concern around 200 people in 31 families in the centre-north of Albania, as follows:

district of Tropoja: 7 families

District of Shkodra: 16 families

District of Koplik: 2 families

District of Mamurras: 2 families

District of Tirana: 2 families

District of Durrës: 2 families

In some cases Operazione Colomba volunteers know both the family that has to decide whether to start a vendetta and also the family that fears it. In other cases, our staff knows only one of the sides (either the family that has to decide whether to start a vendetta or the family that fears it). Dividing these families into two groups, we find:

Families that have to decide whether to pursue vendetta: 11 including:

3 in the district of Tropoja, 5 in the district of Shkodra, 1 in the district of Mamurras, 1 in the district of Tirana, 1 in the district of Durrës.

Families that fear vendetta: 20 including:

4 in the district of Tropoja, 11 in the district of Shkodra, 2 in the district of Koplik, 1 in the district of Mamurras, 1 in the district of Tirana, 1 in the district of Durrës.

The feuding families monitored by Operazione Colomba in Shkodra and Tirana belong mainly to clans from Dukagjin and Tropoja (7 clans in Dukagjin and 4 in Tropoja). More than half have moved within Albania to city suburbs from their mountain areas of origin, often to escape the possible consequences and risks of a blood feud. Movement within the country reduces tension between parties but does not unfortunately guarantee safety as traditional Albanian society is based on relations between extremely extended families that can easily get information on the location of other people. Often the family surname alone is an indication of where it and its members come from, making it easy to find people who move out of a district.

Operazione Colomba does not unfortunately have the resources to monitor how this phenomenon applies across the country. However, based on our own research, including through daily newspapers, we can assume that the number of families involved in blood feuds is greater than reported and that the geographic area involved is wider than that in which the families we ourselves know live. Blood feud is therefore a worrying phenomenon that affects wide swathes of Albania and sometimes other countries too. In the last three years of our presence in Albania, analysis of data in local and international media shows that the phenomenon is spreading and getting worse.

- ROLE OF ALBANIAN INSTITUTIONS IN THE FIGHT AGAINST BLOOD FEUD

The Albanian institutions have dealt with blood feud in different ways over the last few years. Compared with the past when recognition of blood feud was limited, since 2012 the Albanian authorities have made a number of improvements in their handling of it.

International pressure and the higher profile feuding has gained in the local and international media have encouraged the institutions to deal with blood feuds.

The European Union has been the main international organisation to focus specifically on combatting them and indeed has made the eradication of blood feuding one of the conditions of Albania’s entry to the EU. In its 2013 Progress Report[xvi] the European Commission refers to the self-confinement of children, while in a motion for resolution[xvii] that same year the European Parliament pointed out the negative impact of vendetta, and the increase in violence and murder. The European Parliament has also called on the Albanian authorities to set up a statistical database for the phenomenon and a co-ordinating council to contrast blood feud as required under law 9389 of 2005.

In 2014[xviii], 2015[xix] and 2016[xx] the European Union included in the section on protection of the right to life in its Progress Report references to the fight against blood feud, which examined the improvements made by Albania with a view to joining the EU. Each year the EU has called on Albania to make improvements by: setting up a database, implementing the co-ordinating council, strengthening the rule of law and increasing dispute prevention programmes.

In its 2014 Universal Periodic Review the United Nations Human Rights Council recommended that Albania set up a blood feud database and create a co-ordinating council to fight against the phenomenon as required under law 9389/2005[xxi].

Foreign institutions have also shown interest in blood feuds within the context of requests for international protection made by Albanian nationals. In March 2017 the federal commission that receives and decides on requests for international protection made in Belgium published a report written following a visit to Albania to obtain information and get a better understanding of the phenomenon.

4.1. ALBANIAN INSTITUTIONS’ APPROACH TO BLOOD FEUD

The Albanian institutions’ approach to blood feud has gone through a number of stages. Over time the State institutions have had to face up to blood feud and all its consequences. Domestically, the institutions initially tried to deal with the situation from an exclusively legal viewpoint, making vendetta a criminal offence. In 2013 the Albanian Criminal Code was therefore amended to impose tougher penalties on offences committed in connection with a blood feud[xxii]. Article 78/a imposes 30 years’ or life imprisonment on blood feud murder – which thus became an independent offence and not just an aggravating circumstance – while articles 83/a and 83/b impose three years’ imprisonment for threats of confinement and instigation to pursue a blood feud[xxiii].

In 2014 the Shkodra Prosecutor, encouraged by the Tirana General Prosecutor, began to map the families that were victims of blood feud, focusing particularly on self-confined families. An anti-blood feud plan has also apparently been approved by the Directorate General of Police[xxiv]. There have also been cases of police bodies monitoring and controlling vendetta’s situations to prevent their degeneration.

On 5 March 2015 the Albanian Parliament passed a “resolution to prevent blood feuds in Albania”, publicly admitting that they exist and declaring that it is the State’s duty to deal with and eradicate them. It also admitted that the government has not done enough to eradicate them. In the resolution, Parliament condemns the failure to implement law 9389/2005 and requests assistance in this from a number of State bodies: the Police, the Ministry of Education and Sport, the Ministry of Welfare and Youth, and from the public administration as a whole.

The Advocate of the People (Ombudsman), which has been given responsibility for blood feuds by Parliament, has been widely concerned in handling them. In December 2015 it published its second official report on the phenomenon[xxv] in which it recommends implementation of law 9389/2005 and the involvement of a number of Albanian institutions.

Even though law 9389/2005 has not been implemented, initial collaboration began in 2015 in Shkodra, promoted by the OSCE and the Advocate of the People and involving a number of different local government bodies and society itself. Meetings were organised in March, April and September with representatives from the Municipality, the Prefect, Social Services, the Employment Office, representatives from the Prosecutor’s Office and from society in general, including Operazione Colomba. These initial meetings have not however been followed up. In November 2016 the Albanian Interior Ministry promoted a campaign to raise national awareness that might have had an indirect impact on blood feuds. Entitled Mos gjuaj, por duaj! (Don’t Shoot, but Love!), the campaign against the illegal holding of firearms could have helped reduce the number of cases in which a dispute can easily degenerate into a killing[xxvi]. It is the wide holding of firearms and even weapons of war (e.g. kalashnikov rifles) in the country that often leads to irreversible consequences after disputes over minor matters. The campaign was to allow illegally held arms to be handed in without criminal charges up to 30 April 2017. Unfortunately the campaign did not have the desired results and the arms handed over to the police were only a tiny proportion of those that Albanian citizens are assumed to hold. Nevertheless, on 22 May 2017 Albania announced the creation of a National Light Weapons Committee to impose greater control on the holding of weapons in the country.

With regard to the right of access to education, on 13 August 2013 Directive 36 (Procedures for the education of children in self-confinement[xxvii]) was issued. It legally requires local education authorities to implement education programmes for all children identified as being confined in connection with a blood feud. In September 2017 Shkodra’s regional education authority sent the municipalities of Shkodra and Vau Dejes and the local police an order[xxviii] to collaborate and provide information on children in self-seclusion since investigations at local schools had so far failed to identify any child in self-confinement.

With regard to the right to education, a primary school home schooling programme is available (first school cycle or shkolla 9-vjeçare), thus apparently ensuring access to primary education.

Concerning the direct protection of victims however, police investigations have not always produced the desired results. For example, the murder of a 70-year old man and his 17-year old granddaughter on 14 June 2012 in connection with a blood feud has yet to lead to justice being done. The ensuing feud has continued with another attempted murder. If the State cannot provide justice, forms of private justice may re-emerge. Despite the many calls for light on the case by society, the persons guilty of the double murder have not yet been identified. At the same time in another case, pressure from the Advocate of the People encouraged the Prosecutor’s Office to pay particular attention to the needs of the family of the victim of a murder caused by a family feud.

Legal action taken by the Albanian State to toughen penalties does not always produce tangible results when applied. The victim’s family, which is not a party to the criminal proceedings, is often overlooked. The State therefore concerns itself – not always consistently – with punishing the guilty but fails to consider the victims. Focusing on the victims in the Albanian context of family vendettas is essential to reducing the tension between the clans involved and thus avoiding continuation of the feud.

4.2. COLLABORATION BETWEEN ALBANIAN INSTITUTIONS AND OPERAZIONE COLOMBA

- State institutions

Since 2010 Operazione Colomba’s relationship with Albanian institutions has become increasingly one of mutual trust and collaboration. Since the 5000 signatures for life campaign in 2013, a number of institutions have helped collect signatures (including a number of MPs who are members of the Albanian parliament’s parliamentary commissions) and – like the then President of Albania, Bujar Nishani – have praised its aims[xxix].

In 2014 the Albanian institutions promoted and supported the “Change? It’s possible! A crowd moves for peace against blood feud” Peace March launched by Operazione Colomba together with other associations[xxx] to promote: a culture of life, peace, forgiveness and reconciliation; to give a higher profile, including at the international level, to the blood feud problem; and to encourage the Albanian institutions to take a strong stand by implementing in full law 9389 of 4 May 2005. In ten days around 10.000 people had been made aware of blood feuds and reconciliation. The event included the signature by participants and supporters of an appeal stating the aims of the initiative and giving a commitment by all involved to promote reconciliation at the personal, social, legislative and institutional levels. The appeal was signed by 2681 people, almost all of whom were Albanian. In addition to the associations, the Advocate of the People and other representatives of local institutions taking part in the initiative, the appeal was also signed by the then representatives of public institutions: the President of the Albanian Parliament, Ilir Meta, the Minister of Local Affairs, Bledi Çuçi, the President of the Parliamentary Commission for National Security, Spartak Braho, the President of the Parliamentary Commission for Membership of the European Union, Majlinda Bregu and the mayors of Puka and Laç Vau Dejes. Another 253 people living in a number of countries around the world signed the petition on-line. The success of the campaign was reported in Albania and internationally.

In 2015 at the time of the Albanian local elections, Operazione Colomba launched a new initiative to raise national awareness. During the electoral campaign all candidates for the position of mayor were sent a questionnaire about blood feuds in order to get the future representatives of Albanian society to state their real commitment to eradicating the practice. The same questionnaire was also sent to the new mayors to remind them of the commitments they had given their electorates. The results (replies received and failures to reply) have been published on a blog http://www.kundergjakmarrjes.org/ – which is easy to access on-line and is in three languages to make easy reading for the Italian, English and Albanian-speaking publics.

The campaign showed a general lack of interest by local institutions in blood feud. The number of pre-electoral replies received was very small (7 replies from 162 candidates), but this improved after the elections (24 replies from 61 mayors). Another important result was the origin of the replies: most came from the south of the country, the area traditionally least affected by blood feud.

In 2016 another national awareness campaign, “Together we can build Reconciliation!” was launched, focusing on two cities, Shkodra and Tirana, and with two aims: to remember the victims of blood feud and to obtain a commitment from local and national institutions to fight against it. As part of the first aim, a mural was dedicated to the victims of blood feud in Shkodra and a plaque was given to the Palace of Culture in Kamëz (Tirana). Until 2016 there were no monuments or commemorative plaques to the victims of the phenomenon anywhere in the country. This was a way of giving some form of public justice to the victims’ families. As part of the second aim, the institutions, forming part of the Coordination Council on blood feuds, were invited to meet to work together to produce a common strategy against the phenomenon, even though law 9389/2005 had not been implemented.

Events were organised over three days of public meetings attended by the inhabitants of Shkodra and Kamëz, just outside Tirana. Each of the two events included a public meeting in the town square on the subject of forgiveness and reconciliation, a showing of the film The forgiveness of blood and an interview with the leading actress in the film, Sindi Laçej, who also attended and a mural to remember the victims of blood feud which people can still see. Round tables with the institutions were organised in both towns thanks to help from the Advocate of the People. The main aim was to renew the commitment to preventing and fighting against blood feud and to developing a common strategy, as stated in the document that was then produced and shared. Even though a number of institutions did take part in the two round tables, the meetings led to no common initiatives. Institutionally, only the Advocate of the People continued to collaborate in cases of individual families caught up in blood feud.

Recently a number of institutions in the Shkodra area have organised activities in response to the consequences of the phenomenon. In 2015 for example, Shkodra Social Services organised a number of training courses for women belonging to feuding families to help integrate them into the world of work. And since 2016 some members of Shkodra Social Services have become involved with some families reported by Operazione Colomba to help meet a range of social needs. Thanks to the mutual trust that has developed, collaboration is direct and effective.

- Religious institutions

Collaboration with religious institutions has always been real and effective from many viewpoints. In terms of relations with blood feud families, local priests and imams have often handled particular cases alongside volunteers in the field, working together to support the victims in the path towards reconciliation. Representatives from the Catholic Church and the Muslim Myftinia in Shkodra and Tirana have also always taken part in Operazione Colomba awareness campaigns, becoming personally involved in local and national campaigns.

The representatives of the various religious groups in the country have also implemented a range of strategies to fight blood feud. In 2012 the bishops of northern Albania united to issue a letter excommunicating anyone who kills for vendetta and receiving back into the Church only those who repent of their violent acts[xxxi].

In 2014 after the March for Peace, Operazione Colomba met the Papal Nuncio in Tirana and discussed with him its strategy for action to eradicate blood feud.

The Catholic Church also took advantage of the Pope’s visit to launch a proposal of prayers that officially promote a three-stage path to reconciliation: reconciliation with oneself and one’s past; reconciliation with God; reconciliation with others. On this final point the Church made a strong appeal to all feuding families to abandon vendetta.

In March 2017 the diocese of Shkodra gave Operazione Colomba the space and a framework in which to present to the public the book “Il perdono è un bel guadagno” (Forgiveness is a great benefit) intended to support anyone wishing to go down the path of reconciliation to put an end to a blood feud.

- RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on this analysis, Operazione Colomba offers institutions a number of suggestions to help promote the elimination of blood feud in Albania by involving society and feuding families.

- Support mediation between families who are the victims of a blood feud and the creation of a national reconciliation process through restorative justice (see sections 5.1. and 5.2).

- Reform the State justice system through: fight against corruption; pre-trial detention for anyone committing an offence connected with a blood feud; ensure sentences are served; ensure justice is the same for all.

- Introduce legal/institutional instruments that promote the elimination of the phenomenon and recognise and fight anything that causes or prolongs vendetta, such as the law on the civil mediation of disputes[xxxii].

- Amend and implement law 9389 of 4.05.2005 to set up a Coordination Council on blood feuds (see section 5.2).

- Systematically introduce educational and cultural programmes based on the nonviolent management of disputes, education in peace, reconciliation and respect for human rights in schools, places of work and the most highly populated towns.

- Take steps to ensure the safety of Albanians who are the victims of vendetta and to ensure they are able to access basic services (hospitals, places of work, schools, etc.).

- Set up a compensation and support fund for families who are bereaved as a result of vendetta.

- Within the Police, set up an ad hoc emergency service to deal with cases of blood feud.

- Introduce and implement special prison programmes and associated re-education and reintegration plans for prisoners who have committed blood feud offences.

- Introduce standard criteria for identifying families involved in blood feuds.

- Publish official data on the actual extent of blood feuds.

- Create a social State dedicated to dealing with the structural factors that enable the phenomenon to exist and to contributing to the economic and cultural development of society and to the delivery of services.

A number of the above suggestions were stated in 2014 by a delegate of Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII Association in Geneva during the Second Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review of Albania by the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Further work will also be done on several of the suggestions based on Operazione Colomba’s experience and in order to identify best practice for supporting:

– mediation counselling to resolve feuds through reconciliation of the parties;

– implementation of a general reconciliation process to put an end to the entire blood feud phenomenon.

5.1. MEDIATION COUNSELLING

Just as the dynamics of blood feud disputes are changing with time, so the ways they are resolved can also change if this will make them more effective at ending disputes.

Mediation is an alternative dispute resolution technique that brings a third party (who may be an individual, an organisation, community, group etc.) into the dispute. Mediation helps the parties determine the facts, understand the reason for behaviours, accept different viewpoints, identify common interests, recognise that all the parties to a dispute have equal rights and duties, accept the contributions made by the parties and generate new ideas that will lead to agreement.

The Albanian Kanun tradition recognises mediation as a way of resolving disputes and feuds. In the Kanun, reconciliation is the final stage in mediation. Traditional peace-building practices are rooted in local communities and include methods applied from the XIX to the XX centuries, a number of which were taken up again after the collapse of Communism. Traditional approaches are closely linked to the local socio-cultural environment. The code therefore allows two rights/duties: the taking of blood or forgiveness of the other family (see section 1). Forgiveness is achieved through mediation. Mediators are community figures whose moral authority allows them to guide the mediation process by influencing the views and behaviours of the feuding parties. Mediators can be religious figures, bajraktar, missionaries of peace, individuals or clans who are not related to the feuding clans.

Deference is paid to mediators as the expectations of them are high. Depending on local community traditions, the higher the mediator’s social status, the more authoritative and worth of respect his opinion is. For example, in the religious sphere, Catholic and Orthodox priests usually mediate between feuding Catholic and/or Orthodox families with a reconciliation ceremony conducted by a bishop. In Muslim clans, the mediator is an imam, who also seals the reconciliation between them. If the feuding families are of different religions, their religious representatives work together to organise the mediation and together celebrate the reconciliation. Mediators can work alone or in groups to give more weight to their actions. Albanian tradition allows waiver of blood feud through pajtimi i gjakut (blood reconciliation). Until the first half of the XX century, blood peace was based on formal procedures that ended with amicable settlement of the crime thanks to third party intervention, a general besa and collective conciliation at spontaneous assemblies. During long talks mediators sought to achieve an agreement between the parties. Asking that the offender be forgiven and reconciled with his clan involved considerable effort on the part of the victim’s family and could lead to problems for the mediator himself. Pacification was achieved by sending persons of respect and old mediators to emphasise that forgiveness meant honour, burrnija and besa. This could also be achieved through the intervention of several authoritative relatives of the victim. All bereaved family members had to agree to pacification and if the head of the family was very young no decision could be made until he became an adult. The mediators then “dusted down” the old Kanun laws to complete the mediation with blood reconciliation. Reconciliation concluded with a formal ceremony involving the close family, the religious mediators in the home of the victim and the guarantors[xxxiii], or the guarantors along with the heads of the families, the members of the house, the representatives of the House of Gjomarkaj[xxxiv] and the flag. Once the agreement was made, pacification was celebrated by a meal attended by both parties.

Today, these procedures can also include innovative mediation methods. Some of the traditional features of mediation and reconciliation have had to be embedded in the culture while introducing innovation and adapting them to modern feuding to make them more effective in ending disputes. A number of these new procedures are shown below.

- Individuals and independent groups tied to bodies or associations can act as mediators, contrary to tradition. Mediators can also be foreign religious figures since the Kanun is applied in bastardised form and Albanian mediators could find themselves and their own clans threatened.

- Women are involved to improve communication with bereaved women and give them positive advice in the decisions they must make.

- Problem-solving, narrative and transformative types of mediation. Problem-solving mediation seeks to negotiate the interests and needs of both parties. The mediators help the parties think about the negative impact of revenge compared with the positive impact of forgiveness. Mediators can also help achieve a financial agreement, which has been used in the past to indemnify victims. In these cases the third parties have to realise that long-term peace will depend more on full acceptance of the reconciliation decision than on the traditional financial compensation.

Narrative mediation instead involves recognising the pain caused by the dispute and also the hope that transpires through the victims’ narratives and offers a constructive way of ending hostilities. When a third party explains this second aspect, the steps the sides must take to turn the hope into reality become clear. This enables the mediators to help the victims manage and channel their negative emotions constructively while at the same time rationalising their emotional experience to create a new dispute narrative that offers a way of transforming hostile relations.

Transformative mediation changes the way those involved think, through empowerment and mutual recognition. Empowerment increases group and individual understanding of their ability to manage and resolve problems constructively. Recognition promotes understanding, the development of empathy and approval of the other person and his views.

- Sharing, active listening and equivicinanza (equal proximity) to both sides enable the mediator to gain the trust and credibility needed to direct the mediation towards reconciliation. Mediators in feuds between families are able to share the suffering of all involved through active listening. They can help families manage their emotions constructively and channel in a positive direction the anger they feel at the injustice they have suffered. They can help heal emotional wounds. This enables both sides to redefine their pain, bereavement and dispute.

- Dialogue means using words to give positive counselling in family decisions and to build an agreement shared by both sides by moving them towards nonviolent management of their dispute.

- Developing empathy to help the parties put themselves in each other’s shoes, to change the negative perception each has of the other.

- Restorative justice (see section 5.2) using the positive elements of traditional Albanian culture, such as forgiveness and reconciliation can be the catalyst that helps victims of feuds let go of their hate and anger. During counselling, victims can be supported as they explore their personal experiences, while the relatives of the culprit can take concrete action to compensate the victims and make good the damage to them.

- The forgiveness and reconciliation ceremonies may take place in public to ensure long-term peace between the families because they are performed before the community, authoritative religious figures and in sacred places. Publicising the event can also have a positive effect on social pressure.

- Persons whose presence gives support to the parties as they decide in favour of reconciliation, during mediation and after the reconciliation ceremony, ensuring that good relations between both sides are maintained.

Positive social pressure that draws on the positive elements of traditional local culture can also be maintained through awareness action that targets society.

Mediation takes a long time. In many cases, even though the mediation does not lead to official reconciliation between the parties, it does reduce the tension between them and enables the victims of the dispute to continue to lead their lives and get back to normality. The bereaved can start planning their futures. The relatives of the offender can leave fear behind.

5.2 GENERAL RECONCILIATION PROCESS

The general reconciliation process is based on restorative justice, which reintegrates the victims and perpetrators into society. Restorative justice encourages recovery, rapprochement and forgiveness processes in which both victims and killers play an active role. Where the criminal harms or destroys relations between individuals or groups, restorative justice has the task of creating the basis for new relations between them. Restorative justice encourages change in the way the two sides perceive each other by restating and healing the emotions felt by each social player. Victims and killers are rehabilitated by separating the individual or group from the crime, through a process that restores each other’s humanity and in which the narration of personal experience confers dignity on both narrator and listeners.