Scientists Urge WHO to Address Airborne Spread of Coronavirus

COVID19 - CORONAVIRUS, 13 Jul 2020

James McAuley and Emily Rauhala | The Washington Post - TRANSCEND Media Service

6 Jul 2020 – More than 200 scientists from over 30 countries are urging the World Health Organization to take more seriously the possibility of the airborne spread of the novel coronavirus as case numbers rise around the world and surge in the United States.

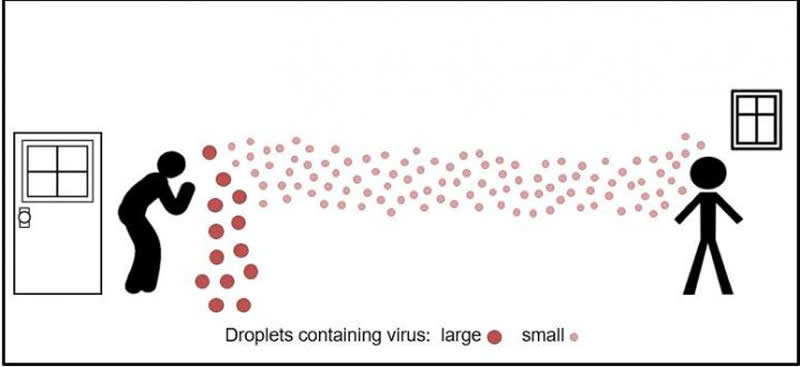

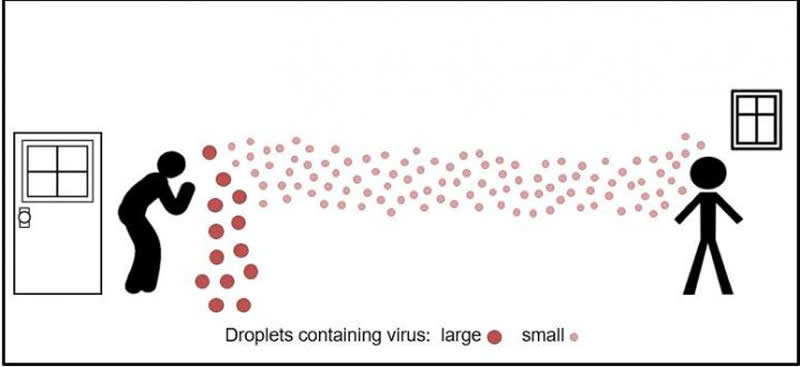

In a forthcoming paper titled “It is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Covid-19,” 239 signatories attempt to raise awareness about what they say is growing evidence that the virus can spread indoors through aerosols that linger in the air and can be infectious even in smaller quantities than previously thought.

Until recently, most public health guidelines have focused on social distancing measures, regular hand-washing and precautions to avoid droplets. But the signatories to the paper say the potential of the virus to spread via airborne transmission has not been fully appreciated even by public health institutions such as the WHO.

The fact that scientists resorted to a paper to pressure the WHO is unusual, analysts said, and is likely to renew questions about the WHO’s messaging.

“WHO’s credibility is being undermined through a steady drip-drip of confusing messages, including asymptomatic spread, the use of masks, and now airborne transmission,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University who provides technical assistance to the organization.

He praised the WHO for hosting regular briefings and acknowledged that the organization is in a tough spot because it “has to make recommendations for the entire world and it feels it needs irrefutable scientific proof before coming to a conclusion.”

But he warned that “the public, and even scientists, will lose full confidence in WHO without clearer technical guidance.”

A spokesperson for the organization said it is aware of media reports about the issue and will have technical experts review the matter. The agency has repeatedly defended its handling of the pandemic.

The WHO, which was founded in 1948, is the U.N. agency tasked with promoting global health. It plays a critical role in expanding access to health care, setting up vaccination programs and fighting diseases such as polio.

But its portfolio has grown faster than its budget. And in times of crisis, it has often struggled to lead.

Since the early days of the coronavirus crisis, the WHO and its director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, have been dogged by questions about whether the agency’s effusive praise for China created a false sense of security and potentially spurred the spread of covid-19, the disease caused by the virus.

That criticism has been compounded at various points by questions about its positions on technical issues, including transmission, mask use — and, now, airborne transmission.

The signatories to the paper contend that the virus can still spread through aerosols, or tiny respiratory droplets, that infected people cough or otherwise release into the air. In crowded or poorly ventilated indoor settings, this could be especially dangerous, and would account for a number of “superspreading” incidents.

“There is no reason for fear. It is not like the virus has changed. We think it has been transmitted this way all along,” said Jose Jimenez, a chemist at the University of Colorado who signed the paper. “Knowing about it helps target the measures to control the pandemic more accurately.”

Co-author Donald Milton, a professor of environmental health at the University of Maryland, said the WHO’s apparent reluctance to emphasize this aspect of the virus’s ability to spread is probably because of the difficulty identifying tiny infectious particles.

“It is easy to find virus on surfaces, on hands, in large drops,” he said in an emailed statement. “But, it is very hard to find much less culture virus from the air — it is a major technical challenge and naive investigators routinely fail to find it. . . .

“Because a person breathes 10,000 to 15,000 liters of air a day and it only takes one infectious dose in that volume of air, sampling 100 or even 1000 liters of air and not finding virus is meaningless.”

Whatever the verdict on transmissibility, the paper is another headache for the WHO as it seeks to lead the response while fending off months of criticism.

In the early days of the crisis, WHO repeated Chinese claims on case numbers and transmission uncritically. When questioned, WHO officials defended Beijing, with the director-general, Tedros, going so far as to personally laud Chinese President Xi Jinping’s leadership.

Tedros’s defenders thought he was merely being diplomatic. It is true that as a member-state organization, the WHO could not compel China to provide accurate data — or march in to collect it.

But by early February, even the organization’s traditional supporters, including current and former advisers, were expressing concern about the praise, worried that the tone was undermining other aspects of the response.

In news conferences, Tedros and other top officials tried to deliver an important message — “test, test, test” — but were often pulled off course by questions about the organization’s ties to China.

As the crisis spread from Asia to Europe and the United States, President Trump seized on the critique, using the agency’s treatment of China to divert attention from shortcomings in the U.S. response.

In April, Trump announced that he was freezing all new funding to the organization. In late May, he said the United States planned to withdraw from the organization.

Jimenez said the scientists’ purpose was not to hurt the agency, but merely to encourage it to consider new information.

“Our group of scientists doesn’t want to do anything that would undermine the WHO as an organization,” he said. “We only want it to adapt its guidance on aerosol transmission to the increasing evidence.”

____________________________________

Emily Rauhala writes about foreign affairs for The Washington Post. She spent a decade as an editor and correspondent in Asia, first for Time magazine and later, from 2015 to 2018, as China correspondent in Beijing for The Post. In 2017, she shared an Overseas Press Club award for a series about the Internet in China.

James McAuley is Paris correspondent for The Washington Post. He holds a PhD in French history from the University of Oxford, where he was a Marshall Scholar.

Go to Original – washingtonpost.com

Tags:

Airborne contagion,

COVID-19,

China,

Community,

Compassion,

Coronavirus,

Cuba,

Economy,

Empathy,

Environment,

Health,

Lockdown,

Pandemic,

Public Health,

Research,

Science,

Science and Medicine,

Semen,

Sharing,

Sperm,

Trade,

United Nations,

WHO,

World

Share this article:

email

mastodon

facebook

🔗 copy link

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.