Disrupting Hate in Education

REVIEWS, 26 Jul 2021

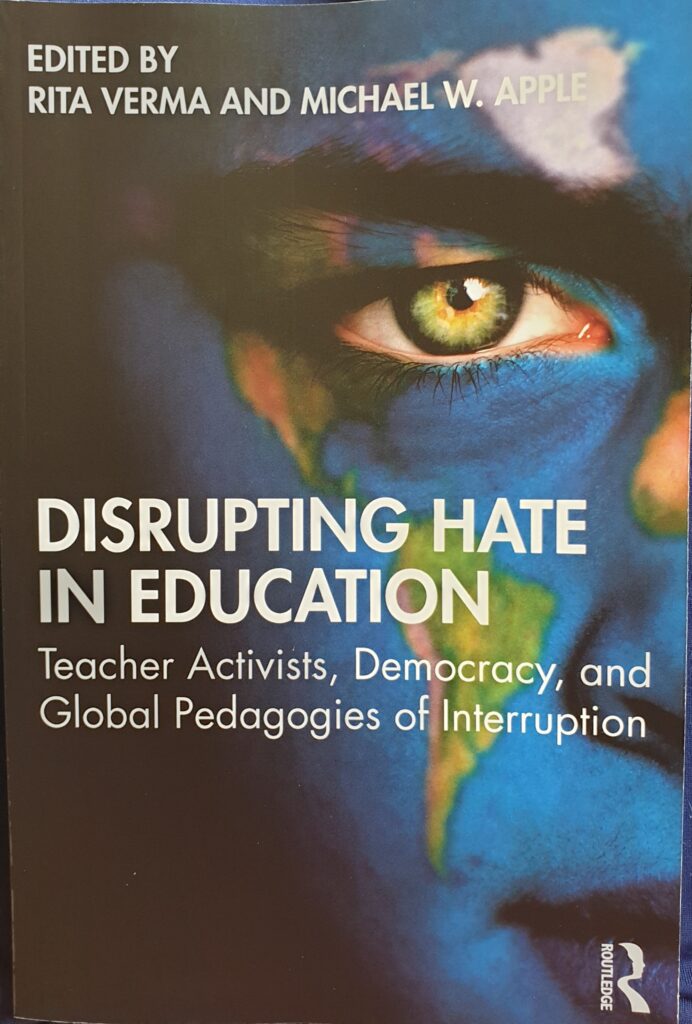

Disrupting Hate in Education, by Rita Verma and Michael W. Apple, Routledge, New York, 242 pp, 2020

21 Jun 2021 – To effectively interrupt dominant narratives of hate, one must first understand them. This is a central theme of Rita Verma and Michael Apple’s co-edited volume, Disrupting Hate in Education: Teacher Activists, Democracy, and Global Pedagogies of Interruption. Featuring ten empirical chapters—four focused on the U.S. and six set in countries across the globe—the book is a timely text. It is firmly situated in the current political moment as it considers both the increasing ubiquity of racist discourse and actions, alongside a hopeful narrative and rich depictions of disruption. Verma and Apple consider the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic as they draw upon notions of populism, nativism, nostalgia, and othering to consider how democratic principles have been upended by political discourses that foment White supremacy and create a “politics of exclusion” (p. 6). Ultimately, the editors call for a reclaiming of “interruptive democracy,” one that requires citizens to challenge oppressive policies before they become normalized in society.

The text works effectively in terms of both specificity and scope. For example, several chapters offer tangible and specific examples that illustrate the ways in which small efforts by individuals and organizations can contribute to broader change, illustrating how seemingly disparate actions can and do build towards collective social action. Verma and Apple conceptualize these examples as “’signposts’ along the complicated landscape of interruption” (p. 13). The volume is also expansive in scope as the editors cover a wide geographic swath, offering portraits of interruption not only in the U.S., but also in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. This book should be read widely—by scholars, educators, practitioners, and anyone interested in understanding and disrupting the role of hate in education.

The first half of the book focuses in on the U.S. context and includes an interview with Maureen Costello, the former director of Teaching Tolerance, which details the dramatic rise in hate crimes under the Trump Administration. The chapter also outlines Teaching Tolerance’s social justice standards as a useful framework for disrupting hate in schools and classrooms. This section also includes a powerful, co-authored chapter by Wayne Au and Jesse Hagopian focused on the Black Lives Matter movement in schools and aptly illustrates ways in which local organizing efforts can have a powerful impact on policy.

Some instances of the text felt repetitive as certain statistics, data, and examples were repeated across multiple chapters related to the U.S. Attention to diversifying some of this data could have deepened the impact of the text as there are countless examples of how hate has manifested and/or been documented, and reaching more broadly to identify these examples might have, in some instances, contributed to more compelling cases. A second critique of the U.S.-based chapters involves mention of social media. While several authors discuss the role of social media in disrupting hate, such as the insightful chapter focused on the aftermath of the Walmart shooting in El Paso, Texas, no mention is made of the ways in which social media can also be responsible for fomenting hate and radicalizing populations in problematic ways. While this text may not be the space in which to problematize social media as a paradigm, it felt under-theorized, especially given the role of social media sites in election tampering, the dissemination of “fake news,” creating echo chambers, and limiting access to civic discourse.

The second half of the book examines the rise of fear, hate, and violence toward minorities, refugees, and women in a diversity of country contexts. The colonial legacies of othering and division feature prominently in chapters on India, South Africa, and Myanmar. In India, Rizwan Ahmad details how the popularism stoked by the current Modi government upholds the ideology of Hindu nationalism and heaps scorn and suspicion on the country’s sizable Muslim minority, who are vilified as “foreign” and a source of societal corruption. Maung Zarni, an activist-educator, similarly chronicles the historical rise of state-sponsored hate against Muslim minorities in Myanmar. Both chapters also highlight the heroic efforts of individuals who are publicly challenging government-backed ideologies of hate. These are historically grounded chapters that illustrate how the Western-backed War on Terrorism has given authoritarian governments the opportunity to unjustly isolate and attack their own Muslim citizens in the name of “national security.”

In contrast, Carol Ann Spreen and Salim Vally’s chapter provides a more theoretically informed assessment of South Africa’s attempts to dismantle apartheid, which, they argue, have been thwarted by the country’s wholesale adoption of Western-backed, neoliberal reforms. Thus, while the South African government’s rhetoric and policy symbols of “a non-racial, equal democratic state” (p. 114) are present, in reality the actions of political leaders contradict these goals and allow inequality along economic and racial lines to persist and grow. Meanwhile, Fernando Penna provides an account of how, since the early 2000s, right-wing populists have developed a pseudo-intellectual network of evidence and thinkers to vilify and foment hate against the country’s public school teachers. The chapter is unique in that it offers a detailed picture of the criminalization of teachers—not based on race, culture, or national origin, but based on accusations of their far-left leanings.

Finally, two chapters illuminate the work of NGOs in the European context. Lynn Davies profiles the work of the U.K.-based organization ConnectFutures, which works with schools and community organizations to examine the causes of violent extremism and to foster resilience, understanding, and connectivity among its participants. Its staff utilizes complexity theory to teach about the pathways toward extremism, a useful approach to understanding the logic of individuals’ trajectories toward hate. In Spain, Marta Soler-Gallart discusses four initiatives—in the form of advocacy research, schools, and an NGO—fighting for the human rights of the Roma people, religious minorities, and refugees. This chapter reminds us that countering hate takes empathy and organization and has a diversity of forms, but would have benefitted from a concluding analysis across the cases.

Verma and Apple conclude with several exhortations including the imperative to make visible the historical facts, human suffering, and the political agendas behind the hate, which have been made invisible in the interests of those in power. Overall, the volume’s authors highlight the need to promote “thick” democracy, based upon an informed citizenry and its collective participation in governing, and reject “thin” democracy in which citizens are deemed consumers, and individual interests and free markets shape society. Furthermore, the authors call on us to generate deeper understandings of how systems contribute to lasting oppression. They also emphasize the need to work with and alongside social movements for change and in solidarity with populations already working to shift unjust societal arrangements.

________________________________________

Emilee Rauschenberger, Ph.D., is a White Rose DTP postdoctoral fellow in Education at Manchester Metropolitan University. She earned her PhD at the University of Edinburgh and is currently working on research that critically examines the global spread of ‘Teach For/First’ programmes through the Teach For All network. On this topic, she recently co-edited a book Examining Teach For All: International Perspectives on a Growing Global Network (2001). She earned degrees from New York University and Johns Hopkins University. Her main areas of interest are international policy transfer, privatization of education, and the influence of policy entrepreneurs. E-mail Author

Katherine Crawford-Garrett, Ph.D., is an associate professor of Teacher Education, Educational Leadership and Policy at the University of New Mexico. She holds a EdD from the University of Pennsylvania as well as degrees from Boston and Colgate universities. Her areas of scholarship include neoliberal contexts of schooling, teacher activism, critical literacy, and feminism. She is the recipient of the 2016 Fulbright US Scholar Award to study TeachFirst NZ, a programme that prepares university graduates in New Zealand to work in low-decile schools. She is also the author of the book Teach For America and the struggle for urban school reform and articles in leading peer-reviewed journals such as the American Educational Research Journal and Teaching and Teacher Education. E-mail Author

Tags: Education, Education for Peace, Hatred, Peace Education, Reviews

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.