Africa and the War on Terror

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 13 Sep 2021

Elizabeth Schmidt | US Foreign Policy - TRANSCEND Media Service

I. Introduction

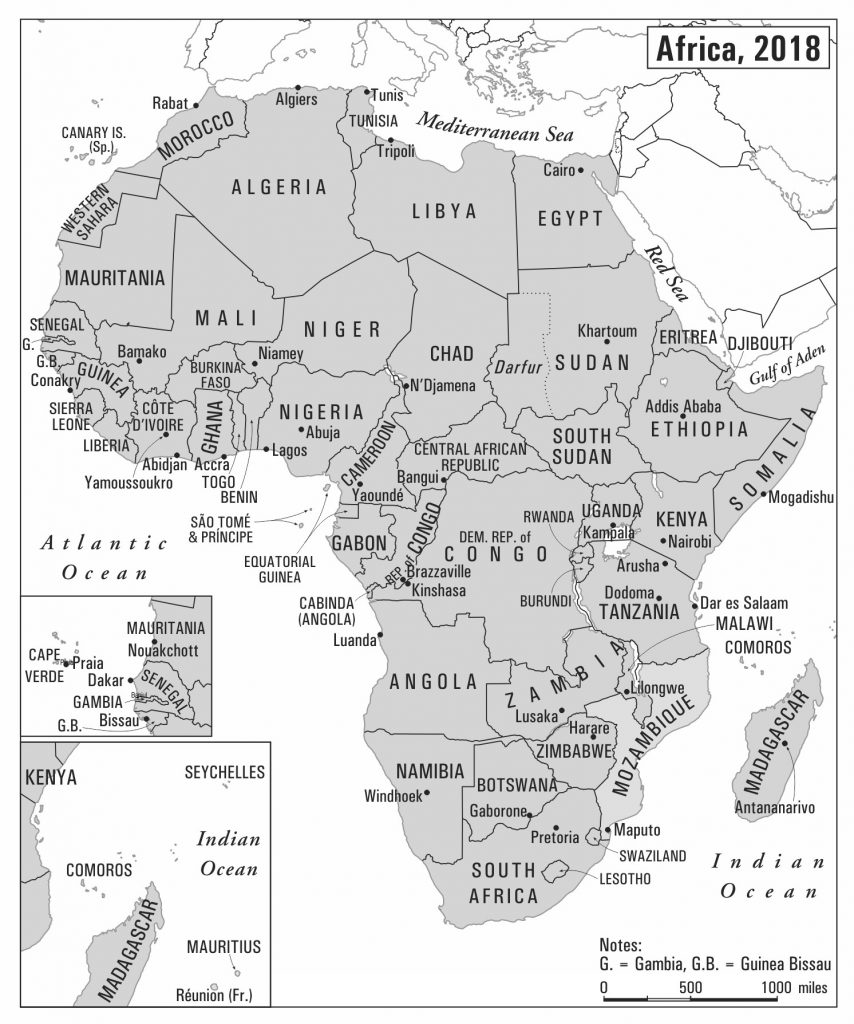

Africa is a continent that is often misunderstood.[1] Outsiders routinely describe it as a place plagued by poverty, corruption, and violence. Although these calamities have affected many African countries, these conditions are by no means universal, and internal actors are not solely responsible. Numerous challenges facing the continent today are the product of colonial political and economic practices, Cold War alliances, and outside intervention in African political and economic systems during the decolonization and post-independence periods. Since the end of the Cold War, the externally-driven war on terror has had a particularly devastating impact on the continent and its people. Western countries, while claiming to promote democracy, self-determination, and human rights, have played an outsized role in interventions that have suppressed indigenous voices and ignored popular will.

To understand the war on terror in Africa, it must be placed in historical context. At the close of World War II, the Cold War intensified, and African struggles for independence escalated. European colonial powers and Cold War superpowers attempted to control the decolonization process. While claiming to champion democracy and self-determination, Western powers deployed military might to promote friendly governments that catered to their own political and economic interests. They considered Africa to be their privileged domain and justified their interventions by harkening to the “communist threat.”

After the Cold War, U.S. Africa policy continued to emphasize military security over humanitarian concerns. However, it paid some attention to the causes of instability and developed programs that focused on the eradication of poverty and disease and the promotion of good governance. The Bush administration’s President’s Malaria Initiative and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Obama administration’s Global Health Initiative (GHI) are cases in point. In the post–Cold War period, the United States offered two new rationales for its interference: the response to instability, with a secondary responsibility to protect civilian lives, and the “war on terror.”

Nigerien soldiers receiving counterterrorism training from U.S. Army Special Forces in March 2017. Later that year, four U.S. Army Special Forces, unfamiliar with the area, were ambushed and killed by violent extremists. Diffa, Niger, March 3, 2017. Photo by U.S. Army Specialist Zayid Ballesteros.

The war on terror, like its Cold War predecessor, has boosted foreign military presence in Africa and increased external support for repressive regimes. U.S. involvement has been especially pronounced. Successive presidential administrations have focused on countries with valuable energy resources and those deemed susceptible to terrorist infiltration. U.S. military aid, arms purchases, and abandoned Cold War weapons have led to intensified violence. Like the war on communism, the war on terror has strengthened autocratic regimes that have abused civilian populations and even increased local support for violent opposition groups.

Case studies from across the continent provide evidence that external military and covert operations have not promoted African security. Rather, they frequently have exacerbated tensions and frustrated prospects for peace. U.S. intervention in Somalia on the Horn, Libya on the Mediterranean coast, and Mali and Niger in the Western Sahel exemplify these trends. The cases of Somalia and Libya are examined below.

II. The Cold War Roots of the War on Terror

The two current rationales for foreign intervention have very different roots. The first, which justifies external interference as a legitimate response to instability and the endangerment of civilian lives, can be traced to post-World War II recognition that peace, justice, and respect for human rights are required for a stable international order. The second, which exchanged the war on communism with a war on terror, originated in the Cold War struggle between capitalism and communism.

During the Cold War, the United States deployed religion in the battle against communism. In Europe, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) bolstered conservative Christian parties in an effort to blunt the appeal of communism to populations devastated by World War II. In the Middle East, the CIA impeded radical nationalism by shoring up autocratic regimes that opposed communism and offered access to the region’s oil riches. Where nationalists overthrew pro-Western strongmen, their secular governments, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser’s in Egypt (1952–70), were opposed by Islamists, who believed that a nation’s social, political, and legal order should be grounded in Islamic principles. The secular regimes responded with repression, arresting and imprisoning local Islamists and forcing others into exile.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to advance its regional interests, the United States marshalled support from a Muslim minority who opposed the Soviet occupation with violence. Working with Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and other allies, the United States mobilized a multinational coalition that recruited, trained, armed, and financed Muslim militants worldwide to fight the Soviet presence. After Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the militants scattered with their arms and training to countries across the globe, where they established new organizations and spearheaded countless insurgencies, primarily against Muslim states they deemed impious. These Soviet-Afghan War veterans played prominent roles in most of the extremist groups that appeared in Africa and the Middle East in the decades that followed.

Osama bin Laden, founder and patron of al-Qaeda, was among the most prominent of the Soviet-Afghan War veterans who launched the emerging terrorist networks. As the Soviet Union declined and collapsed, Bin Laden and his associates targeted the United States – as the last remaining superpower and patron of impious Muslim regimes. Al-Qaeda was responsible for a number of attacks on U.S. citizens and property, which culminated in the September 11, 2001, strikes on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Young boy in Beni, North Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of Congo, playing near a United Nations vehicle, December 5, 2014.

Photo by Abel Kavanagh/MONUSCO.

III. 9/11 and the War on Terror

Like the war on communism, the war on terror has strengthened autocratic regimes that have abused civilian populations and even increased local support for violent opposition groups.

The war on terror paradigm is largely identified with the George W. Bush presidency. However, it emerged during the Bill Clinton administration and played a significant role in the Africa policies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump. During all four administrations, perceived national interests, embracing political, economic, and strategic dominance, were key factors in determining where the United States chose to intervene or not intervene. The responsibility to protect paradigm increasingly served as a rationale for intervention only when other interests were also at stake.

Before the September 11, 2001 attacks, the war on terror played only a minor role in U.S. Africa policy. The 1993 U.S. military intervention in Somalia, for instance, was triggered by the threat of regional instability and a growing concern with the protection of civilian lives in a region deemed critical to U.S. interests. Although the United States provided significant monetary and material support to United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations in the 1990s, after the Somalia debacle (see below) it avoided multinational ventures that might involve U.S. troops, and it actively blocked UN intervention to stop the 1994 Rwanda genocide because it did not consider Rwanda a place of strategic or economic value.

After 9/11, the George W. Bush administration’s war on terror became the new anticommunism. Just as domestic unrest sparked by local grievances was mistaken for communist aggression during the Cold War, the misnomer, “international terrorism,” was used to explain disparate civil disturbances in the first decades of the twenty-first century. In Africa, autocrats who had appealed to the West by harkening to the communist menace were replaced by new strongmen who won Western support by joining the fight against terrorism. In both cases, unpopular leaders used U.S. military aid to suppress internal dissent, and U.S. policies undermined the goals they purported to promote. Instead of bringing peace and stability, U.S. counterterrorism policies strengthened repressive regimes and opened the door to domestic warlords and foreign occupiers. As unrest intensified, violent extremists seized the opportunity to harness local grievances and gain a foothold in territories they previously had not penetrated.

Following the 2001 attacks, U.S. Africa policy was reassessed, with three important results. First, Washington paid more attention to poverty and political dysfunction. Poor nations with weak state institutions were viewed as likely breeding grounds for political extremism – now characterized as terrorism rather than communism. The United States bolstered African economies, strengthened military alliances, opened military bases, and provided money, training, hardware, and equipment to dozens of strategically located African countries that were considered vulnerable to terrorist activity. It also provided air support in conventional military actions and engaged in a growing number of covert military operations.

Second, the securitization of U.S. Africa policy privileged military security over broader forms of human security that focused on poverty, disease, climate change, and governance. The Pentagon took charge of humanitarian and development assistance programs that replaced others under civilian authority. The counterterrorism programs of the Defense Department and the CIA encroached upon, and largely supplanted, the human security/human rights agenda of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Their programs, established in response to terrorism, were often inadequate for the peacekeeping and peace-building tasks now under their authority.

Third, target countries were chosen according to new criteria. The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 sparked violence and instability that threatened U.S. access to its customary sources of foreign oil, and the anti-foreign insurgency was characterized as a terrorist menace. Africa felt the ripple effects as Washington focused increasingly on countries that were either rich in oil and natural gas or strategic to the war on terror. Such countries were often controlled by corrupt, authoritarian regimes that distributed resource proceeds to cronies and loyalists and deployed U.S. military equipment and training against political opponents and community activists. In many cases, U.S. aid increased domestic repression and intensified local grievances.

The 9/11 attacks marked the beginning of a new era of U.S. military intervention, first in Central Asia and the Middle East, and then in Africa. During the Cold War, the United States had confounded radical African and Arab nationalism with communism and implicated itself in conflicts it did not understand. It supported brutal regimes and insurgencies, whose abuse of local populations had catastrophic results. When the U.S. government launched the war on terror, simplistic views again prevailed. Many in the government viewed the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims as a monolith and failed to distinguish between nonviolent Muslims with conservative religious beliefs and a tiny minority who used violence to achieve their ends. They made no distinction between those with longstanding local grievances who targeted tyrannical regimes and a much smaller group who attacked the countries that supported these rulers, oppressed Muslims, or defiled Muslim holy lands.

After 9/11, the Bush administration expanded unconventional military actions in Africa, deploying U.S. Special Operations Forces and launching unmanned drones outside of established war zones. The International Commission of Jurists condemned as “legally and conceptually flawed” the U.S. government’s “conflation of acts of terrorism with acts of war” and concluded that “the use of the war paradigm has given a spurious justification to a range of serious human rights and humanitarian law violations.”[2]

While Washington professed support for “African solutions for African problems,” successive U.S. administrations used African soldiers to implement American solutions to protect American interests.

The 2007 establishment of the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), a unified military command that oversees U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine activities in Africa, signaled the growing importance of Africa to U.S. security concerns. Previously, responsibility for U.S. military activities on the continent had been divided between the European, Central, and Pacific Commands, underscoring Africa’s peripheral status in the broader geopolitical arena. As in the past, U.S. rather than African security concerns dominated AFRICOM’s agenda. While Washington professed support for “African solutions for African problems,” successive U.S. administrations used African soldiers to implement American solutions to protect American interests.

Countering al-Qaeda’s expansion topped new U.S. security concerns in Africa. By the second decade after 9/11, al-Qaeda had developed two important branches in Africa: al-Shabaab (The Youth), which was based in Somalia and launched attacks in the Greater Horn; and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which was active in North Africa and the Western Sahel. Al-Qaeda also supported a number of local affiliates and associated organizations, most of which had emerged in response to local grievances and had sought political, material, and propaganda aid after they were established.

Washington’s secondary concern was the expansion of the Islamic State, which had emerged in response to the U.S.-led military intervention in Iraq in 2003. The U.S. invasion, ouster of Saddam Hussein, and military occupation ignited a local insurgency led by the Jordanian-Palestinian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who transformed his local organization into al-Qaeda in Iraq. After Zarqawi’s death in a U.S. airstrike in 2006, his successors dubbed the al-Qaeda branch and associated groups the Islamic State in Iraq. Under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who developed his ideas in a U.S. internment camp, the Islamic State mobilized recruits among the Sunni minority that had been favored under Saddam Hussein but was marginalized after his overthrow. While local jihadist groups have aspired to establish or purify a Muslim state within a given country, the Islamic State strives to establish a global caliphate that would unite Muslims in a single political entity. African organizations that have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State leader, like those associated with al-Qaeda, ordinarily emerged from local conditions and only later established ties to the international jihadist organization.

IV. Misconceiving Islam

Since 9/11, the U.S.-led war on terror has inspired or reinforced many misconceptions about Islam. The emergence of diverse political movements operating under Islam’s banner has led to much confusion over how to distinguish them. Terms with different meanings are often used interchangeably. Disparate groups are lumped together and terminology apt for one is used to describe the whole. For instance, Islamism, an ideology and movement focusing on social, political, and religious life, has been confused with Islamic fundamentalism, which concerns religious doctrine. Political Islam – one aspect of Islamism – is often wrongly described as political terrorism. Only a tiny minority of Muslims worldwide condone political terrorism, while the vast majority disavow its association with their religion. Finally, the Arabic word jihad is regularly mistranslated as “holy war” and linked with images of death by the sword. In Islam, however, there are three meanings of jihad, two of them nonviolent. The following definitions lay the groundwork for a more accurate understanding of contemporary Islam.

Islam is the name of a world religion with two main branches, Sunni and Shi’a.

Islamic fundamentalism refers to Islamic beliefs that reject recent religious innovations and advocate a return to basic religious principles and the strict application of religious law. The vast majority of Islamic fundamentalists are law-abiding and oppose violent jihad.

Islamism is a twentieth century social, political, and religious ideology and movement that arose in response to European colonialism and the intrusion of Western culture. Its followers strive to establish a social, political, and legal order that is rooted in Islamic principles. They focus on social and political change rather than on religious doctrine and work within the system to achieve their ends. Islamists, in contrast to jihadis (defined below), reject the use of violence.

Political Islam is sometimes used synonymously with Islamism, even though it constitutes only one aspect of a complex ideology and movement.

Jihad means effort or struggle. In Islamic doctrine, it has three meanings: first, the inner spiritual struggle to live as a good Muslim; second, the struggle to build and purify the Muslim community; and third, the struggle to defend the faith from outsiders. The first meaning is the most important and lays the foundations for the other two. Most Muslims believe that preaching and proselytizing are the best ways to achieve their goals. However, Western observers have generally reduced all forms of jihad to one, wrongly defined as a “holy war” against nonbelievers. Ironically, the concept of holy war originated among Christians in medieval Europe to justify crusades against Muslims in the Holy Land; it has no direct counterpart in established Islamic thought.

Jihadism, is a term that emerged in the West after 9/11. It refers to a minority insurgent movement that broke from Islamism and employs violence in the name of religion. Nourished by deep social, political, and economic inequalities and persecution, its adherents are primarily young men who are alienated from mainstream society. Initially, jihadis targeted local secular and Muslim regimes that they considered impure. More recently, a small minority of jihadis have widened their targets to include non-Muslim states that back the impure Muslim regimes. Commentators in the United States often overlook these distinctions, merging Islamism and jihadism under the misleading rubric of “Islamic terrorism,” which wrongly associates religious doctrine with terrorist activity.

Muslims who engage in terrorism and claim religious justification for these activities are a small minority of Muslims worldwide, and their actions are strongly condemned by the majority.

In sum, Islamic fundamentalism, Islamism, and political Islam are not equivalent to Islamic terrorism. Muslims who engage in terrorism and claim religious justification for these activities are a small minority of Muslims worldwide, and their actions are strongly condemned by the majority. Although these violent extremists deploy the language of religion to justify their actions, their turn to terrorism was often sparked by social, political, and economic grievances rather than religion. When establishment figures in the U.S. view all of these movements as a threat to Western societies and thus base militaristic policies on caricatures and misconceptions, they victimize innocent civilians, intensify hostility toward the United States, and heighten U.S. insecurity.

V. Case studies: Somalia and Libya

The U.S. war on terror has undermined U.S. interests. It has also been catastrophic for Africa. Evidence from across the continent supports these claims. The cases of Somalia in the east and Libya in the north exemplify the pattern of U.S. actions subverting both U.S. and African interests.

Somalia

The war on terror in Somalia, as elsewhere, is rooted in Cold War policies and practices. During that period, Mohammed Siad Barre’s repressive regime played on superpower rivalries, relying first on the Soviet Union and then on the United States. As the Cold War waned and Siad Barre was no longer valued as a regional policeman, Washington, citing Siad Barre’s human rights abuses, suspended military and economic aid. In 1991, warlords and their militias overthrew the weakened regime. The central government collapsed, state institutions and basic services crumbled, the formal economy ceased to function, and southern Somalia disintegrated into fiefdoms ruled by rival warlords and their militias. Islamists, who had been repressed by the Siad Barre regime, challenged the warlords for control.

War-induced famine, worsened by drought, threatened the lives of much of the population. Concerned about regional instability, first the United Nations, and then the United States, intervened. In 1992, the UN Security Council authorized the establishment of a US-led multinational military task force to ensure the delivery of humanitarian relief. In 1993, another UN mission, also led by the United States, permitted military personnel to forcibly disarm and arrest Somali warlords and militia members. As a result, the United States took sides in what had become a civil war – favoring one warlord and opposing another.

U.S. Marines participate in a UN Task Force search for Gen. Mohammed Farah Aidid’s weapons. Mogadishu, January 7, 1993.

Photo by U.S. Navy photographer Terry C. Mitchell.

As the United States embroiled itself in Somalia’s war, it generated enormous resentment within the civilian population. When U.S. Special Operations Forces attempted to capture key militia leaders in October 1993, and Somali militias shot down two Black Hawk helicopters, angry crowds attacked the surviving soldiers and their rescuers. Eighteen U.S. troops and some one thousand Somali men, women, and children were killed in the ensuing violence. Having stirred up the hornets’ nest, the United States and UN hastily withdrew from Somalia, and the turmoil intensified. The emergence of al-Qaeda in East Africa in the mid-1990s sparked new U.S. concerns. Al-Qaeda–sponsored bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 and the organization’s attacks on the United States in September 2001 led to increased U.S. collaboration with Ethiopia, Somalia’s regional nemesis.

Meanwhile, in Somalia, Islamist groups that had been repressed by the Siad Barre regime gained widespread popular support by providing essential social services no longer furnished by the government. They offered schools, medical care, and courts to enforce law and order in a violent war zone. The Somali public supported these efforts, and business owners financed their activities. Some Islamist groups, like secular movements before them, strove to build a Greater Somalia, uniting ethnic Somalis who had been separated by regional and colonial states. Ethiopia, whose territory included a significant Somali population, grew alarmed. Warning that Somalia could become an al-Qaeda outpost, Washington joined Somali warlords and the Ethiopian government in opposing Islamist advances.

Foreign imposition of a corrupt, Ethiopian-backed government (2004), CIA support for a new warlord coalition in violation of a UN arms embargo (February–June 2006), and a U.S.-sanctioned Ethiopian invasion and occupation (July 2006–January 2009) resulted in an anti-foreign backlash that intensified popular support for al-Shabaab, which was transformed from a youth militia organized to defend the Islamic courts into a violent jihadist organization that quickly gained the support of al-Qaeda. Somali veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War assumed an important leadership role.

The fallout from foreign intervention rapidly turned the Somali conflict into a regional conflagration. Whereas the UN tacitly condoned the Ethiopian offensive, the United States actively supported it, referring to the invasion as a legitimate response to aggression by Somali Muslim extremists. Joining forces with those who opposed Islamist influence, Washington launched a low-intensity war against al-Shabaab operatives, deploying both private contractors and U.S. Special Operations Forces. U.S. personnel trained and advised African partners, participated in raids, and interrogated prisoners. U.S. drones and air strikes targeted and killed key al-Shabaab leaders, who were quickly replaced by others. These actions turned al-Shabaab’s attention to the West. The organization began to target Western aid workers, journalists, and Somalis who worked with them.

The joint Ethiopian-U.S. operation resulted in an increase, rather than a decrease, in chaos and violence. Within weeks of the foreign invasion, a homegrown insurgency had begun, rallying al-Shabaab and other Islamic courts militias, clans that had been marginalized by the foreign-backed government, and a wide range of groups that benefited from anarchy, including warlord militias, hired gunmen, arms and drug traffickers, smugglers, and profiteers. Responding to al-Qaeda’s call, fighters from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Arabian Peninsula joined the Somali insurgents. As al-Shabaab took control of large swaths of central and southern Somalia, the UN and African Union intervened, neighboring countries such as Ethiopia and Kenya interceded to push their own agendas concerning territorial boundaries and Muslim populations, and al-Shabaab extended its targets to include them. Within a decade, two new extremist organizations emerged and pledged allegiance to the leader of the Islamic State.

Rather than paving the way for stability, the U.S.-led war on terror provoked an insurgency in Somalia that consumed thousands of civilian lives and destabilized the region. Human rights organizations accused all sides of war crimes. Human Rights Watch charged that “the Ethiopian forces . . . appeared to conduct deliberate attacks on civilians, particularly attacks on hospitals.”[3] They also bombed densely populated areas and collectively punished civilians, raping and killing with impunity. Insurgents had engaged in assassinations and summary executions and mounted attacks from crowded neighborhoods that bore the brunt of Ethiopian and Somali government retaliation. Multiple peace initiatives failed. Somali civil society had not been included in the negotiations. The ensuing agreements, which did not address the underlying grievances, gained little internal support, and a succession of weak, foreign-backed governments could not provide even basic services and security. The vicious cycle of brutality by opposing forces intensified, trapping civilians in the crossfire. In short, U.S. support for the unaccountable Somali government brought greater mayhem, rather than peace, to the region.

Libya

In Libya, as in Somalia, the foreign-backed war on terror brought greater insecurity to the region – not peace. Once again, the United States played a leading role.

The war on terror in Libya was also rooted in the Cold War, when the autocratic government of Muammar Qaddafi assumed power. Qaddafi’s anti-imperialist rhetoric, socialist policies, nationalization of the Western-dominated oil industry, and the presence of Soviet arms and advisors convinced the U.S. that Libya was a Soviet proxy – despite the regime’s repression of communists. To maintain his grip on power, Qaddafi, governed through family, clan, and tribal ties, and promoted social cleavages that kept potential rivals weak. He destroyed any institution that might challenge him. As a result, Libya had no parliament, trade unions, political parties, or nongovernmental organizations.

After the Cold War, Libya and Western countries found common cause in their shared opposition to those who embraced violent jihad, including Libyan veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War. Determined to end Libya’s pariah status and to revive foreign investment in the oil industry, Gaddafi cooperated with the West on counterterrorism issues. He renounced terrorism, destroyed Libya’s biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons stockpiles, and abandoned its weapons of mass destruction programs. UN and European Union arms embargoes and U.S. economic sanctions were lifted. European and U.S. interests began to invest heavily in Libyan oil and natural gas exploration and production, and European countries helped Libya upgrade its military. In exchange for billions of dollars in trade, investment, and weapons deals, Qaddafi helped European countries staunch the flow of illegal migrants from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe – halting African refugees and job-seekers on Libyan shores, where they were herded into detention camps and low-wage employment.

Qaddafi’s attempts to work with the West were thwarted by the Arab Spring (2011–13). As prodemocracy demonstrators and rebel movements ousted repressive rulers across North Africa and the Middle East, foreign nations and multigovernmental organizations allied with forces they hoped would protect their interests. International terrorist networks led by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, took advantage of local grievances to support a wide range of violent extremists, including drug smugglers, human traffickers, and petty criminals, as well as indigenous groups fighting secular or supposedly impious Muslim governments.

In February 2011, inspired by popular uprisings elsewhere in the region, Libyan protesters and insurgents began an all-out rebellion against the Qaddafi regime. Qaddafi’s foreign allies quickly abandoned him. The UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo. The Arab League suspended Libya’s membership and initiated contact with Libyan rebels. Western governments imposed economic sanctions and froze Libyan assets. As Qaddafi turned his military against civilian and insurgent strongholds, rebel leaders urged the international community to impose a no-fly zone that would prevent the Libyan air force from attacking civilians. The result was a UN-authorized, NATO-led military intervention – ostensibly to protect civilian lives, but with regime change as an unofficial objective.

In October 2011, a U.S. Predator drone and a French warplane fired on Qaddafi’s convoy, enabling rebel forces to capture and execute the ousted ruler. Without institutions to fill the power vacuum, regime change provoked the collapse of the social order. Qaddafi’s departure unleashed score-settling and retribution by groups pitted against one another during his tenure. Local militias, warlords, and violent extremists moved into the power vacuum, seizing unprotected weapons from Qaddafi’s arsenals and absorbing his crack military troops and mercenaries.

What had begun as peaceful protests devolved into a violent conflict between allies and opponents of the old regime and between factions within these camps. Radical youth challenged elders who had served the Qaddafi government. Rival towns fought to control of Libya’s vast oil, natural gas, and gold reserves as well its energy infrastructure, ports, airports, and central bank. Moderate Islamists struggled with secularists, and both groups opposed violent extremists, including Libyan veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War and foreign fighters who had answered al-Qaeda’s call to join the rebellion.

By 2014, Libya had become a new hub for al-Qaeda and the Islamic State and was deeply embroiled in civil war. The UN Security Council did not authorize a peacekeeping operation to support peacekeeping or nation-building. Its mission failed to protect civilians from further violence or to safeguard Qaddafi’s weapons stockpiles. Libyan arms flooded into neighboring countries and made their way to insurgencies in North Africa, the Western Sahel, the Horn, and the Middle East, arming secular insurgents, religious extremists, and criminals.

In Libya, as in Somalia, the foreign-backed war on terror brought greater insecurity to the region – not peace. Once again, the United States played a leading role.

VI. Lessons learned

What lessons can be learned from the recent history of U.S. military intervention in Africa?

Most importantly, military solutions don’t work. U.S. drone and missile strikes have killed countless unarmed civilians, increasing local support for insurgent forces. Military successes have been short-lived, as violent extremists have regrouped and shifted their focus to unprotected civilians. Local governments backed by the United States and its allies rarely address the structural problems that triggered the conflicts. As a result, civilian populations, neglected by their governments, have sometimes turned to extremist groups for income, basic services, and protection that their governments have not provided. Peace agreements, imposed from above and outside, have failed to give voice to affected populations. Jihadist organizations have been denied a seat at the bargaining table, even though they are critical parties to the conflicts. Not surprisingly, most of the accords have collapsed.

Contrary to popular U.S. stereotypes, religion and ethnicity are not the root causes of African conflicts. Deeper structural inequalities are at work: poverty, underdevelopment, and political repression – as well as the devastating impact of climate change. The encroaching desert in Darfur (western Sudan) has pitted herders against farmers in the struggle for water and usable land; the drying up of Lake Chad has devastated fishing and agriculture in four countries and sparked the Boko Haram insurgency; and the destruction of the fishing industry by foreign trawlers has led to piracy off the coast of Somalia, are cases in point.

U.S. Africa policies, developed during the Cold War, were conceived by leaders and proponents of the military-industrial complex. Marked by militarism and misunderstanding, they have failed to identify the true factors that undermine human security. As a result, U.S. Africa policy has offered wrong-headed solutions that often exacerbate the problem. The post-9/11 war on terror has led to particularly grievous results.

If the issue is not how many troops, planes, and drones the U.S. should supply, what should the U.S. do?

To promote an effective response to violent extremism in Africa, the United States needs to revamp its approach in four important ways.

To promote an effective response to violent extremism in Africa, the United States needs to revamp its approach in four important ways.

First, the U.S. must broaden its understanding of “national interests” and “national security.” Like President Trump’s America firsters, establishment liberals tend to view U.S. national security primarily in military terms that focus on the maintenance of U.S. global power and interests against perceived threats. Instead, the United States should embrace a more exacting concept of global human security that includes access to good food, water, health care, education, employment, physical security, and respect for human rights, civil liberties, and the environment as factors critical to human well-being. The safeguarding of global human security is a precondition for U.S. security. It requires a multidimensional approach that addresses and remedies the root causes of problems that threat the world today.

Second, the U.S. needs to acknowledge that it does not have the answers and to seek out those who do. Grassroots endeavors – organized by African-led agricultural cooperatives, trade unions, and women’s and youth groups – are already addressing the grievances that spring from poverty and inequality and the conflicts that result. They have lived the experience and have developed the best solutions. They must guide U.S. policy choices.

Since the early 1990s, African pro-democracy movements have demanded better education, employment, health care, clean water, sanitation, electricity, and roads, along with programs to rehabilitate rank-and-file fighters and counter future violent extremism. They have insisted on the need for responsive, democratic governments that respect the rule of law, eliminate corruption, and address climate change, pollution, and the inequitable distribution of resources. They have called for an end to harsh counterinsurgency campaigns and to the impunity of military and police personnel who have engaged in human rights abuses. Their voices should be heard, and their experiences and solutions should be seriously considered.

Third, the United States and its allies should support local peace initiatives that include all affected parties. Key actors, including Islamist and jihadist groups, should not be sidelined at their discretion.

Finally, the United States should withdraw its support for corrupt, repressive regimes and instead advance U.S. and multilateral initiatives that promote democracy, human rights, and economic, environmental, and climate justice.

The only path to greater U.S. security is greater human security worldwide. History has shown that there will be no peace if underlying grievances are not addressed, if domestic and foreign militaries continue to victimize local populations, and if dysfunctional states fail to provide basic services. Boko Haram, for example, will not be effectively countered as long as the Nigerian government continues to brutalize and punish local populations. These concerns are longstanding, and there are no easy fixes or short-term solutions. Although fundamental political, economic, and social transformations will take decades, they are the only solution to crises in Africa and the global south.

Endnotes:

[1] Material for this article is derived from Elizabeth Schmidt, Foreign Intervention in Africa after the Cold War: Sovereignty, Responsibility and the War on Terror (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2018), and from Elizabeth Schmidt, “Lessons from Africa: Military Intervention Fails to Counter Terrorism,” Foreign Policy in Focus (FPIF), March 26, 2020, https://fpif.org/lessons-from-africa-military-intervention-fails-to-counter-terrorism. A free PDF download of the book is available through Open Access, found on the Ohio University Press website: https://www.ohioswallow.com/book/Foreign+Intervention+in+Africa+after+the+Cold+War

[2] Assessing Damage, Urging Action: Report of the Eminent Jurists Panel on Terrorism, Counter-terrorism and Human Rights (Geneva: International Commission of Jurists, 2009), 49.

[3] Human Rights Watch, Shell-Shocked: Civilians Under Siege in Mogadishu (August 13, 2007), p. 5, https://www.hrw.org/report/2007/08/13/shell-shocked/civilians-under-siege-mogadishu.

_______________________________________________

Elizabeth Schmidt is professor emeritus of history at Loyola University Maryland. A scholar-activist, she has written about U.S. involvement in apartheid South Africa, women under colonialism in Zimbabwe, the nationalist movement in Guinea, and foreign intervention in Africa from the Cold War to the war on terror. Her books include: Foreign Intervention in Africa after the Cold War: Sovereignty, Responsibility, and the War on Terror (2018); Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror (2013); Cold War and Decolonization in Guinea, 1946-1958 (2007); Mobilizing the Masses: Gender, Ethnicity, and Class in the Nationalist Movement in Guinea, 1939-1958 (2005); Peasants, Traders, and Wives: Shona Women in the History of Zimbabwe, 1870-1939 (1992); and Decoding Corporate Camouflage: U.S. Business Support for Apartheid (1980).

Go to Original – peacehistory-usfp.org

Tags: Africa, Africom, Cold War, Colonialism, Colonization, Corruption, Decolonization, Democracy, Europe, Hegemony, Imperialism, Pentagon, State Terrorism, USA, War on Terror, West

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: