Jane Goodall (Born 3 Apr 1934)

BIOGRAPHIES, 28 Mar 2022

Biography – TRANSCEND Media Service

Animal Rights Activist, Scientist

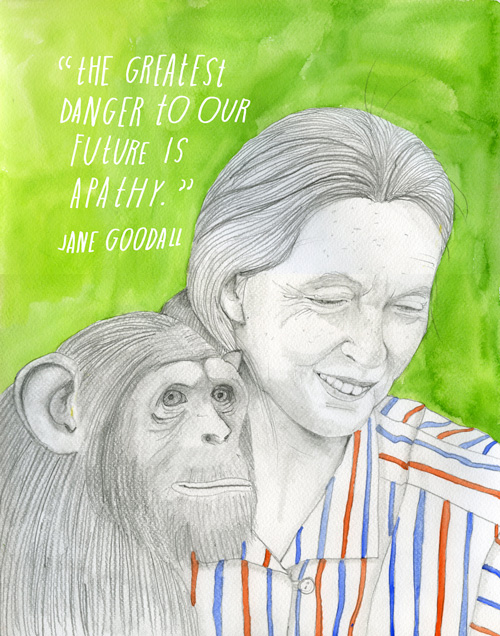

Jane Goodall is known for her years of living among chimpanzees in Tanzania to create one of the most trailblazing studies of primates in modern times.

Who Is Jane Goodall?

Born on April 3, 1934, in London, England, Jane Goodall set out to Tanzania in 1960 to study wild chimpanzees. She immersed herself in their lives, bypassing more rigid procedures to make discoveries about primate behavior that have continued to shape scientific discourse. A highly respected member of the world scientific community, she advocates for ecological preservation through the Jane Goodall Institute.

Jane Goodall Movies

The general public was introduced to Jane Goodall’s life work via Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, first broadcast on American television on December 22, 1965. Filmed by her first husband, and narrated by Orson Welles, the documentary showed the shy but determined young English women patiently watching these animals in their natural habitat, and the chimpanzees soon became a staple of American and British public television. Through these programs, Goodall challenged scientists to redefine the long-held “differences” between humans and other primates.

In 2017, additional footage from the Miss Goodall shooting was pieced together for Jane, a documentary that included recent interviews with the famed activist to create a more encompassing narrative of her experiences with the chimps.

Jane Goodall Institute

Many of Goodall’s endeavors are conducted under the auspices of the Jane Goodall Institute for Wildlife Research, Education and Conservation, a nonprofit organization that promotes the protection of chimpanzees and strong environmental practices. Founded in 1977, the organization is based in Virginia but boasts some two dozen offices around the world.

Observing Chimps in Africa

In July 1960, accompanied by her mother and an African cook, Jane Goodall arrived on the shore of Lake Tanganyika in the Gombe Stream Reserve of Tanzania, Africa, with the goal of studying chimpanzees.

Goodhall’s first attempts to closely observe the animals failed; she could get no nearer than 500 yards before the chimps fled. After finding another suitable group to follow, she established a nonthreatening pattern of observation, appearing at the same time every morning on the high ground near a feeding area along the Kakombe Valley.

The chimpanzees soon tolerated her presence and, within a year, allowed her to move as close as 30 feet to their feeding area. After two years of seeing her every day, they showed no fear and often came to her in search of bananas.

Chimp Behavior Discoveries

Goodall used her newfound acceptance to establish what she termed the “banana club,” a daily systematic feeding method she used to gain trust and to obtain a more thorough understanding of everyday chimpanzee behavior. Using this method, she became closely acquainted with a majority of the reserve’s chimps. She imitated their behaviors, spent time in the trees and ate their foods.

By remaining in almost constant contact with the chimps, Goodhall discovered a number of previously unobserved behaviors: She noted that chimps have a complex social system, complete with ritualized behaviors and primitive but discernible communication methods, including a primitive “language” system containing more than 20 individual sounds. She is credited with making the first recorded observations of chimpanzees eating meat and using and making tools. Tool making was previously thought to be an exclusively human trait.

Goodhall also noted that chimpanzees throw stones as weapons, use touch and embraces to comfort one another and develop long-term familial bonds. The male plays no active role in family life but is part of the group’s social stratification: The chimpanzee “caste” system places the dominant males at the top, with the lower castes often acting obsequiously in their presence, trying to ingratiate themselves to avoid possible harm. The male’s rank is often related to the intensity of his entrance performance at feedings and other gatherings.

Upending the belief that chimps were exclusively vegetarian, Goodall witnessed chimps stalking, killing and eating large insects, birds and some bigger animals, including baby baboons and bushbacks (small antelopes). On one occasion, she recorded acts of cannibalism. In another instance, she observed chimps inserting blades of grass or leaves into termite hills to insects onto the blade. In true toolmaker fashion, they modified the grass to achieve a better fit, then used the grass as a long-handled spoon to eat the termites.

Jane Goodall’s Books

Goodall’s fieldwork led to the publication of numerous articles and books. In the Shadow of Man, her first major work, appeared in 1971. The book, essentially a field study of chimpanzees, effectively bridged the gap between scientific treatise and popular entertainment. Her vivid prose brought the chimps to life, revealing an animal world of social drama, comedy and tragedy, although her tendency to attribute human behaviors and names to chimpanzees struck some critics being as manipulative.

Goodall outlined the moral dilemma of keeping chimpanzees captive in her 1990 book, Through a Window: “The more we learn of the true nature of nonhuman animals, especially those with complex brains and corresponding complex social behaviour, the more ethical concerns are raised regarding their use in the service of man—whether this be in entertainment, as ‘pets,’ for food, in research laboratories or any of the other uses to which we subject them,” she wrote. “This concern is sharpened when the usage in question leads to intense physical or mental suffering—as is so often true with regard to vivisection.”

Her 1989 work, The Chimpanzee Family Book, written specifically for children, sought to convey a more humane view of wildlife. The book received the 1989 UNICEF/UNESCO Children’s Book of the Year Award, and Goodall used the prize money to have the text translated into Swahili and French and distributed throughout Tanzania, Uganda and Burundi.

Book Controversy

In March 2013, Goodall attracted media attention for her book Seeds of Hope: Wisdom and Wonder from the Plants, with Gail Hudson. The book had not yet hit store shelves when Goodall was accused of plagiarism. According to The Washington Post, the famed scientist borrowed sections from Wikipedia and other sources in her new book without giving them proper credit.

The publisher subsequently announced the release of the book would be delayed to address the unattributed sections. Goodall, through a statement from her institute, apologized for these unintentional mistakes: “This was a long and well researched book, and I am distressed to discover that some of the excellent and valuable sources were not properly cited, and I want to express my sincere apologies,” she said. Seeds of Hope was reissued in 2014.

Marriages and Family

In 1962, Baron Hugo van Lawick (1937-2002), a Dutch wildlife photographer and filmmaker, was sent to Africa by the National Geographic Society to film Goodall at work. The assignment ran longer than anticipated and the couple fell in love; they were married on March 28, 1964, and their European honeymoon marked one of the rare occasions on which Goodall was absent from Gombe Stream. In 1967, she gave birth to a son, Hugo Eric Louis, known as “Grub.”

After divorcing van Lawick in 1974, Goodall was married to Derek Bryceson (1922-1980), a member of Tanzania’s parliament and director of its national parks, until his death from cancer.

Early Years and Interest in Animals

Jane Goodall was born on April 3, 1934, in London, England, to Mortimer Herbert Goodall, a businessperson and motor-racing enthusiast, and the former Margaret Myfanwe Joseph, who wrote novels under the name Vanne Morris Goodall. Along with her sister, Judy, Goodall was reared in London and Bournemouth, England.

Goodhall’s fascination with animal behavior began in early childhood. In her leisure time, she observed native birds and animals, making extensive notes and sketches, and read widely in the literature of zoology and ethology. From an early age, she dreamed of traveling to Africa to observe exotic animals in their natural habitats.

Goodall attended the Uplands private school, receiving her school certificate in 1950 and a higher certificate in 1952. She went on to find employment as a secretary at Oxford University, and in her spare time also worked at a London-based documentary film company to finance a long-anticipated trip to Africa.

Learning from Anthropologist Leakey

Learning from Anthropologist Leakey

At the invitation of a childhood friend, Goodhall visited South Kinangop, Kenya, in the late 1950s. Through other friends, she soon met the famed anthropologist Louis Leakey, then curator of the Coryndon Museum in Nairobi. Leakey hired her as a secretary and invited her to participate in an anthropological dig at the now famous Olduvai Gorge, a site rich in fossilized prehistoric remains of early ancestors of humans. Additionally, Goodall was sent to study the vervet monkey, which lives on an island in Lake Victoria.

Leakey believed that a long-term study of the behavior of higher primates would yield important evolutionary information. He had a particular interest in the chimpanzee, the second most intelligent primate. Few studies of chimpanzees had been successful; either the size of the safari frightened the chimps, producing unnatural behaviors, or the observers spent too little time in the field to gain comprehensive knowledge.

Leakey believed that Goodall had the proper temperament to endure long-term isolation in the wild. At his prompting, she agreed to attempt such a study. Many experts objected to Leakey’s selection of Goodall because she had no formal scientific education and lacked even a general college degree.

Professorships and Educating the Public

Goodall’s academic credentials were solidified when she received a Ph.D. in ethology from Cambridge University in 1965; she was just the eighth person in the university’s long history permitted to pursue a Ph.D. without first earning a baccalaureate degree. Goodall subsequently held a visiting professorship in psychiatry at Stanford University from 1970 to 1975, and in 1973, she was appointed to her longtime position of honorary visiting professor of zoology at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

After attending a 1986 conference in Chicago that focused on the ethical treatment of chimpanzees, Goodall began directing her energies toward educating the public about the wild chimpanzee’s endangered habitat and about the unethical treatment of chimpanzees that are used for scientific research.

To preserve the wild chimpanzee’s environment, Goodall encourages African nations to develop nature-friendly tourism programs, a measure that makes wildlife into a profitable resource. She actively works with business and local governments to promote ecological responsibility.

Goodall’s stance is that scientists must try harder to find alternatives to the use of animals in research. She has openly declared her opposition to militant animal rights groups who engage in violent or destructive demonstrations. Extremists on both sides of the issue, she believes, polarize thinking and make constructive dialogue nearly impossible.

While reluctantly resigned to the continuation of animal research, she feels that young scientists must be educated to treat animals more compassionately. “By and large,” she has written, “students are taught that it is ethically acceptable to perpetrate, in the name of science, what, from the point of view of animals, would certainly qualify as torture.”

Accolades

In recognition of her achievements, Goodall has received numerous honors and awards, including the Gold Medal of Conservation from the San Diego Zoological Society in 1974, the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize in 1984, the Schweitzer Medal of the Animal Welfare Institute in 1987, the National Geographic Society Centennial Award in 1988, and the Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences in 1990. More recently, she was named a Messenger of Peace by the United Nations in 2002 and a Dame of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II of England in 2003.

Go to Original – biography.com

Tags: Activism, Biography, Jane Goodall

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.