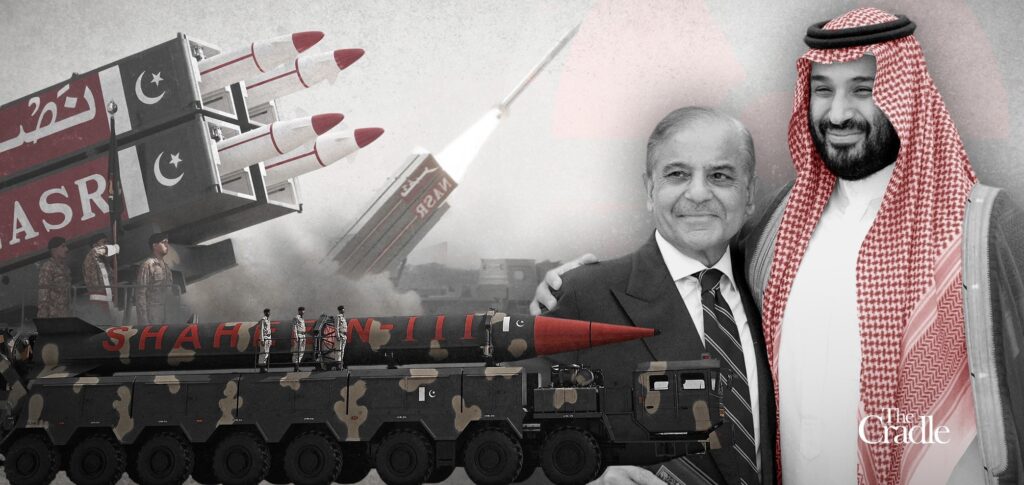

Accompanying him on the trip was Pakistan’s Army Chief, Field Marshal Asim Munir. His presence highlighted that Riyadh values its defense pact with a nuclear power that, despite economic challenges, remains militarily strong.

Nuclear umbrella over Riyadh

The centerpiece of their visit was the signing of a “Strategic Mutual Defense Agreement” (SMDA), which declares that an attack on either country will be considered an attack on both.

Described by a senior Saudi official to Reuters as covering “all military means,” the pact has triggered speculation that it includes a nuclear umbrella, which would be a game-changing development in the military balance of West Asia.

With 81 percent of Pakistan’s weapon imports coming from China, the agreement implicitly aligns Saudi Arabia with the Chinese military-industrial orbit, whether by design or default. The kingdom has long been reliant on US arms, training, and security guarantees.

The pact was signed just two days after an extraordinary joint session between the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) was called, following the 9 September Israeli airstrikes on Qatar – a major non-NATO ally and Gulf neighbor – with no substantial response from Washington, reinforcing perceptions that western security commitments are both selective and expendable.

Mushahid Hussain Syed, a former information minister and chairman of Pakistan’s Senate Defense Committee, tells The Cradle that the US has pivoted away from Arab allies toward Tel Aviv, leaving the region disillusioned and increasingly leaning toward alternatives.

“The strategy of ‘Greater Israel,’ spearheaded by Netanyahu, has involved military actions against five more Muslim nations. Pakistan’s recent triumph against India has demonstrated its capacity to contest Israel’s significant ally, India, and establish itself as a strategic alternative for Gulf nations.”

Toward an Islamic NATO?

Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani recently called for an Islamic military alliance, akin to NATO, in response to Israel’s airstrike on Doha. His proposal echoed Egypt’s earlier attempt to revive a joint Arab defense force under the 1950 treaty – an initiative blocked by Qatar and the UAE, reportedly under US pressure.

A similar proposal has also come from Islamabad when Pakistan’s Defense Minister, Khawaja Asif, urged Muslim countries to band together in a NATO-like military alliance in light of the Israeli aggression in Doha.

During an appearance on Geo TV last week, Asif drove home the point that a united Muslim military front is essential to tackle common security issues and fend off outside dangers. Asif invoked the wider role of the west in instigating instability in West Asia, emphasizing the intricate network of US support for Al-Qaeda and the CIA’s covert actions that led to Osama bin Laden’s relocation to Sudan or the regime change war in Syria.

Is nuclear deterrence a part of the Pact?

The nuclear dimension of the Riyadh–Islamabad pact remains opaque, but highly significant. While no official statement from either side confirms the presence of a nuclear component, Asif hinted that Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities could be shared with Saudi Arabia as part of the agreement.

Syed, however, clarifies to The Cradle that Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine is India-centric and that its deterrence posture is South Asia-specific and does not extend to the Persian Gulf.

“A novel security framework for the region appears to be taking shape, focusing on Global South nations such as Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, whereas the Indo-Israeli Axis, previously supported by the US, now finds itself significantly diminished.”

The defense agreement between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, he says, represents a notable achievement for Pakistan, establishing it as a pivotal entity within the geopolitical framework of West Asia, particularly among Muslim countries.

“The agreement is shaped by three significant elements: the perceived neglect of Arab allies by the United States, Israel’s proactive maneuvers in areas such as Iran, Qatar, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, and Pakistan’s recent triumph over India in May.”

New Delhi, Tel Aviv on alert

Foreign media and analysts are already warning that the pact may have unintended consequences for India and Israel, despite claims that it targets neither. Others predict that this pact is really about Riyadh’s ambitions to counter Iran and Yemen’s Ansarallah-led government in the region.

Dr Abdul Rauf Iqbal, a senior research scholar at the Institute for Strategic Studies, Research and Analysis (ISSRA) at Islamabad’s National Defence University (NDU), tells The Cradle that New Delhi views the pact with unease as it formalizes Saudi–Pakistani security ties that could entangle Riyadh in South Asian rivalries, especially the India–Pakistan border tensions over Jammu and Kashmir:

“It represents a setback for Prime Minister Modi’s foreign policy, potentially leading to Saudi involvement in a prospective Indo–Pak conflict. Furthermore, future Saudi investments in Pakistan’s Gwadar port and economic corridors would challenge India’s regional influence and initiatives such as the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC).”

He adds that Saudi Arabia’s pivot toward Pakistan reflects a broader alignment of Muslim powers and could push Tel Aviv to recalibrate its war on Gaza. It also pressures Tel Aviv by placing Pakistan – a vocal opponent of Israeli expansionism – into West Asian affairs.

“This agreement is not meant to counterbalance Iran’s regional influence, but rather to promote the Saudi Iranian reconciliation, as Pakistan maintains friendly relations with both nations. By formalizing ties with nuclear-armed Pakistan, Riyadh secures a credible deterrent as US security guarantees weaken. While western think tanks view it as an effort to contain Iran, the Arab world emphasizes it as strengthening Gulf deterrence independently of Washington.”

Indian concerns also stem from fears that the pact’s NATO-style clause could complicate ongoing operations like Sindoor, which remains active in a limited capacity following the skirmish between the two nuclear powers in May, especially given that the Gulf states’ swift mediation to resolve the crisis reflects their own interests with India and makes any military action against it unlikely.

Secondly, India is strategically analyzing Pakistan’s nuclear capability, which could see a boost if Saudi Arabia, having no such capacity, begins channeling funds to share Pakistan’s nuclear assets.

A post-western Gulf order?

While Tel Aviv and New Delhi remain publicly silent, both capitals are undoubtedly scrutinizing the fallout. Israel’s failed assassination attempt on Hamas leaders in Qatar, and India’s pressure campaign along the Line of Control, suggest that the axis is nervous about the consequences of a Saudi–Pakistani alliance. Israeli media downplayed the Saudi–Pakistan defense deal, seeing it as a show of force after Riyadh failed to influence Trump or West Asian policy.

As Syed notes, “The traditional ‘Oil for Security’ framework, which once defined US relations with the Middle East [West Asia], now serves as a remnant of a bygone era. As Saudi economic power increasingly reinforces China’s backing of Pakistan, India may feel vulnerable and isolated.”

Mark Kinra, an Indian geopolitical analyst with a focus on Pakistan and Balochistan, tells The Cradle that this development holds particular significance for India. New Delhi, he argues, has sustained robust economic and diplomatic ties with Saudi Arabia for many years, and the influx of Saudi investments in India continues to expand:

“India will be meticulously observing the progression of this agreement, particularly given that its specific terms are not publicly available. Any alteration in the regional security equilibrium may influence India’s strategic assessments, energy security, and diplomatic relations.”

As Washington’s selective security guarantees falter and Israel escalates unchecked, Persian Gulf states like Saudi Arabia are looking eastward for credible deterrents and strategic autonomy.

By aligning with nuclear-armed Pakistan, Riyadh is asserting greater independence from the western military order. It also signals the emergence of a multipolar Persian Gulf security architecture –one increasingly shaped by Global South coordination, not western diktats.

______________________________________________

F.M. Shakil is a Pakistani writer covering political, environmental, and economic issues, and is a regular contributor at Akhbar Al-Aan in Dubai and Asia Times in Hong Kong. He writes extensively about China-Pakistan strategic relations, particularly Beijing’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

F.M. Shakil is a Pakistani writer covering political, environmental, and economic issues, and is a regular contributor at Akhbar Al-Aan in Dubai and Asia Times in Hong Kong. He writes extensively about China-Pakistan strategic relations, particularly Beijing’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).