Memories of the Future

PAPER OF THE WEEK, 6 Oct 2025

Gianmarco Pisa – TRANSCEND Media Service

Monumental Heritage and Redefinition of Hopeful Public Space in Former Yugoslavia

2 Oct 2025 – Myth, memory, and their respective “places”, conceived both physically and figuratively, can represent powerful carriers of contents, ideals, and symbols, and incisive factors in the configuration, definition, and signification of the public space. While the function of tangible cultural heritage in defining and shaping public space is widely recognized and studied, and its urban and topographical potential is well-known in literature, the pre-assumptions of such function deserve further exploration. Myth, as a synthetic ideopoetic narrative, capable of representing and synthesizing, in a symbolic and narrative form, ideals and stories of the past, activating them into the present, fuels the inspiration to shape cultural and monumental emergencies. Memory, in the form of collective memory and based on a cultural memory of the past, unfolds, through the figures it celebrates and the events it commemorates, the specific places of culture and memory, with artistic testimonies and cultural assets that represent both symbols and signals, alerts and warnings in public space. The complex of cultural heritage and places of memory and culture shape the urban space, open rooms to creative transformation, and generate authentic memorial topographies, infusing the urban space with memorial and cultural significance, consequently shaping the complexity of public space. In the territorial space of former Yugoslavia, particularly in Kosovo and its cities of Pristina, Mitrovica, the project, based on an action-research application, named H.E.R.M.E.S. (Heritage-based Education and Research Measures for Empowerment and Sharing), identifies and studies these memorial topographies through the identification of a true spatial constellation of places of culture and memory, shaping the cities and orienting their ideologies. The aim, in a space marked by the legacies and divisions brought about by war, is to prefigure public spaces open to transformation and hope, in the sense of the transformative potential of grassroot work for reconciliation, coexistence, and peace.

Dealing with «social frameworks of memory», Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945) describes the features of those socially organized and culturally oriented relational contexts where individual memory can find meaning, and collective memory can be arranged in public space, in the space of the city, as a true “social construct” [1]. In such public scenario, the collective memory can become a powerful “mythical vector” [2]. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi (1932-2009) addresses the topic of remembrance in terms of historical memory, defining events and processes through which a collective memory molds a community identity, shaping the connection between memory, myth and the organization of public space, where precisely this “memorial celebration” takes place [3].

Cultural heritage as tangible representation of myths

Based on the forms of collective memory and springing from the ritual of belief, the myth is a projective representation, a comprehensive manifestation, that opens spaces and chances to celebrate, in a synthetic form, one or more salient features of the people’s narration, one or more unifying contents to project into the future, towards which to mobilize or under which to activate.

The myth contains a certain, more or less determined, evocation of the past and a corresponding, more or less defined, aspiration towards the future. It intervenes to expand the content of the narrated historical events; and, in doing so, it helps to illustrate values and ideals of a given community: values of courage and justice, heroism and solidarity, compassion or redemption.

The myth comes to summarize a descriptive content and a programmatic attitude: it synthesizes through images a heritage of beliefs, legends, values, and, turning to the future, it orients behaviours, providing the necessary keys for the community to define its socio-cultural position and articulate its ideo-political development, in terms of needs to be satisfied, values to be nurtured, ideals to be confirmed.

Beyond their interpretation as «places of memory», according to the description suggested by Pierre Nora (1931-2025), some cultural heritages can become tangible representations of myths. In the case of the history of the so-called “second” Yugoslavia (1945-1991), through the watermark of the tragic experience of the ethno-political conflict and the complex need for new spaces of intercultural coexistence, some of these heritages define places of extraordinary importance, for the substratum of collective memories they condense and the mythical content they convey [4].

Topographies of memory for peace and coexistence: the Yugoslav case

Yugoslavia’s cultural heritage defines a proper «topography of memory». As a manifestation of public art and, specifically, “monumental sculpture in open spaces”, they take on a commemorative and topographical public function, because they serve to nourish the collective memory of the founding historical events and contribute to defining the form of the places of citizenship.

As places of culture, memory, and citizenship, characterizing and affecting the use of public space, they also represent a transformative element of urban space. Since a social group does not possess any memory in itself, it needs to be connected to symbolic objects, conceived as alerts or warnings, such as monuments, memorials, museums, and any other institution of memory.

These heritages act both in terms of regeneration of a collective memory and preservation of contents of meaning (values, assumptions, ideals) enucleated by those cultural goods: the fight against oppression; the resistance against the evil; the liberation from tyrannies and injustice; the movement towards freedom; solidarity and peace; «unity and brotherhood» among peoples.

Although there is no accurate census of such monumental heritage in the public spaces of the Yugoslav period, with estimates ranging from a few thousand to even forty thousand monumental emergencies [5], it is clear that, to the extent they have survived the destruction brought by the wars of the 1990s, they can serve both aims: they can transform the surrounding urban space, making it the site of initiatives of public participation, territorial animation and urban regeneration; and they can contribute to overcoming the post-conflict divisions, nurturing a culture of peace, respect and coexistence [6] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Map of the places of memory in Yugoslav public space as recognized and studied in the frame of H.E.R.M.E.S. project and available on the project’s website: https://corpicivilidipace.com/memorials

In Kosovo, after the 1990s war, some of these heritages outline authentic «mythopoetic topographies». On the two slopes of Kosovo Polje’s field there are two memorials, the Gazimestan Tower (Kulla), commemorating the deeds of the Serbian prince Lazar Hrebeljanović (1329-1389) (Fig. 2), and the Sultan Murad I Mausoleum (Türbe), with the tomb of the Ottoman ruler Murad Hüdavendigâr (1326-1389). The legendary chronicles and epic cycles, such as the “Kosovo Polje Cycle”, with the figures of the above mentioned prince Lazar and the legendary knight Miloš Obilić (Fig. 3), also contribute to continue the celebration of such mythologies [7].

Fig. 2: Gazimestan Tower (Kulla), Kosovo Polje, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

Fig. 3: The statue to the knight Miloš Obilić, Gračanica, Kosovo, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

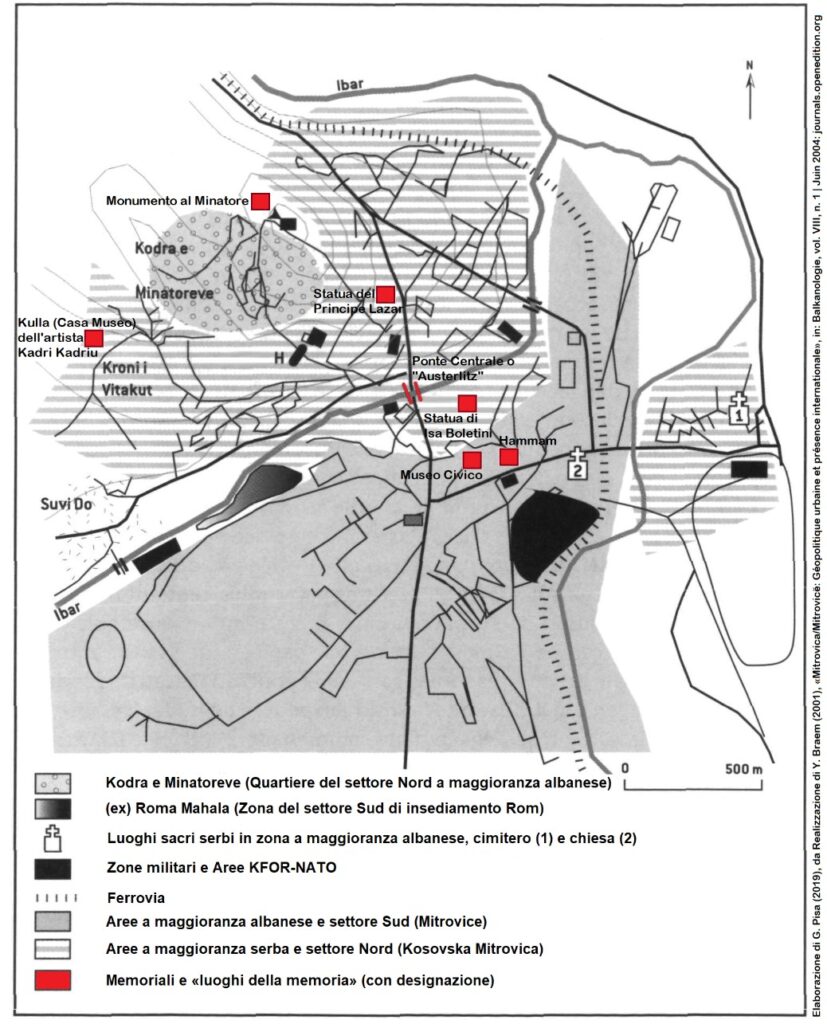

This representation of the myth finds a salient place in the “divided city” of Mitrovica, Kosovo, along the “diagonal” (Fig. 4) of the Main Bridge (after the war representing the Confidence area or Buffer zone between the two separated city sectors, whose division along ethnic lines is one of the most painful legacies of the war of the Nineties) that separates the two areas, at whose ends stand two of the most heartfelt monuments, the statue of Isa Boletini (1864-1916), leader of the Albanian independence, in the Albanian sector (Mitrovicë), and the statue of Prince Lazar (1329-1389), leader of the Christian forces in Kosovo Polje, in the Serbian sector (Kosovska Mitrovica).

Fig. 4: The memorial topography of the city of Mitrovica (Kosovo), elaboration by Gianmarco Pisa (2019) based on a realization by Yann Braem (2001), «Mitrovica/Mitrovicë: Géopolitique urbaine et présence internationale», Balkanologie, v. VIII, n. 1 | 2004: https://doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.515

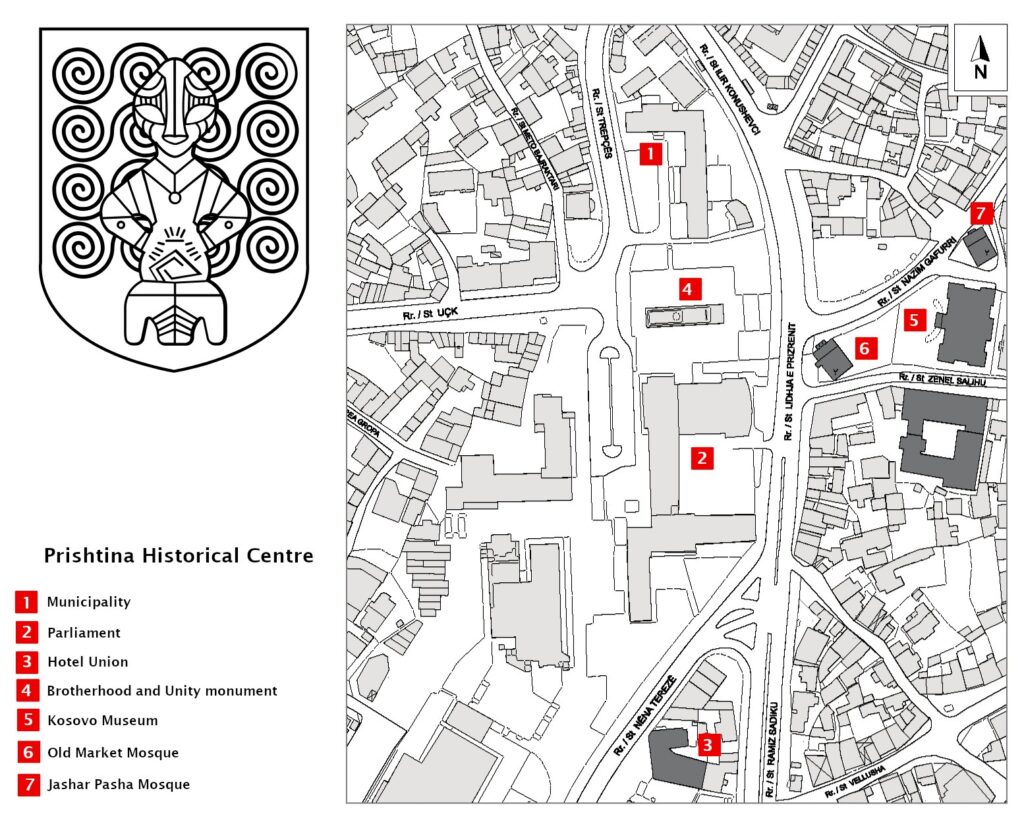

A completely different configuration can be found in the city of Prishtina, the main city of Kosovo, where the effects of the urban reconfiguration, carried out since the 1950s, under the banner of the Yugoslav motto “Uništi stari graditi novi” (“Destroy the old, build the new”) are more visible [8], but where it is possible to see, on both sides of the main axis crossing the city centre (the avenue named after Agim Ramadani, an Albanian commander of the separatist Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, but in Yugoslav time named after Ramiz Sadiku, an Albanian partizan of the Peoples’ Liberation War), the two urban nuclei (Fig. 5), with the respective characterizing places of memory: to the west, the Yugoslav aggregate, with the civil buildings and the Monument to Brotherhood and Unity; to the east, the Ottoman aggregate, with the few surviving ancient houses and the two main mosques of the city.

Despite the unity of this urban fabric, the presence of distinct memorial topographies is also effective, with their specific public space configuration and their historical and cultural memory sediment.

Fig. 5: The memorial topography of the city of Prishtina (Kosovo), elaboration by Gianmarco Pisa (2025) based on a realization by Cultural Heritage Without Borders (CHWB 2008), Heritage of Prishtina: https://it.scribd.com/document/887800241/CHWB-Heritage-of-Pristina-Report12-2008.

As for the memorials, a mythopoetic prominence is assumed by the «Miner’s Monument» (Fig. 6), dedicated to the miners, Albanian and Serbian partisans, fallen in the anti-fascist liberation struggle, in Kodra Minatorëve (an ethnically mixed area in the Serbian majority sector of Kosovska Mitrovica), a work by Bogdan Bogdanović (1973); the «Brotherhood and Unity Monument» (Fig. 7), dedicated to the anti-fascist liberation struggle and the coexistence between the Yugoslav peoples, in Prishtina, a work by Miodrag Živković (1961); as well as, again in Kosovo, the «Monument to the Peoples’ Liberation Struggle» (Fig. 8) in Fushë Kosova, by Miodrag Živković (1985) as well.

These monumental emergencies continue to mark important places of the urban contexts: respectively, the Kodra Minatorëve hill, overlooking the western side of Kosovska Mitrovica and the slope towards the Ibar river; one of the main squares in the city centre of Prishtina, named after Adem Jashari, one of the leaders of the separatist Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, but in Yugoslav time named after the “Brotherhood and Unity” among peoples; and finally, in Fushë Kosova, the main square (Freedom Square) just in front of the train station. As long as they resist the ongoing attempts at removal and destruction, these monuments will continue to design “topographies of hope” and positively address, in the sense of coexistence, to the urban configuration of these cities.

Fig. 6: The Miner’s Monument, Mitrovica, Kosovo, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

Fig. 7: The «Brotherhood and Unity» Monument, Prishtina, Kosovo, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

Fig. 8: The Monument to the Peoples’ Liberation Struggle, Fushë Kosova (Kosovo Polje), by Gianmarco Pisa.

A culture-oriented action-research for peace building

By questioning the survival of such images of the past in public space, the action-research project H.E.R.M.E.S. (Heritage-based Education and Research Measures for Empowerment and Sharing) [9], developed with the association IPRI-CCP (Italian Peace Research Institute – Civil Peace Corps) [10], aims to identify such contents of the Yugoslav heritage, as meaningful places of memory and culture, shaping the form of the city and supporting a culture of peace and coexistence in public space, both in their memorial (cultural) value and in relation to their transformative (social) potential.

As Vesa Sahatçiu wrote: «Former Yugoslav monuments, together with objects, streets, parks and squares, are not simply Serbian. They are Yugoslav. And because Albanians were part of it, the monuments remain part of our heritage. […] It’s clear that these monuments, even today, are not Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian, Montenegrin, Macedonian nor Albanian. […] Resurgent nationalist sentiments leave no room for monuments with no national identity. There’s no space for these relics when some are busy rewriting history. Who needs monuments that are neither entirely Serbian, nor entirely Albanian, but consist of both?» [11]. Issues of Yugoslav heritage, their historical grounds and values, can activate a culture of memory and trigger positive insights, rich in meanings for the present epoch.

Yugoslav heritage provides a valid example in both senses: as stage of conflict events, in whose watermark it is possible to glimpse the interactions between nationalities and cultures; and as places of a long and rich cultural heritage, whose monuments, cultural institutions, and museums, always offer significant examples of education to memory, culture and peace. It is possible to trace an echo of the cultural complexity of those territories in some specific museums, where the local features dialogue with the different cultural influences and multicultural backgrounds, such as the Sevdah Art House, in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the City Museum of Mitrovica, Kosovo.

The Sevdah Art House is located in the historical core (Baščaršija) of Sarajevo (Fig. 9) and is devoted to the art of Sevdalinka, the traditional Bosnian folk song from the urban areas. It is characterized by a melancholic content with allusions and symbols and it is said to be originated from the ancient poems of love and death, and the Greek tragic poem as well, transmitted through oral tradition [12].

Fig. 9: The historical core (Baščaršija), Sarajevo, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

On the other side, the City Museum of Mitrovica, Kosovo, is one of the most important museum spaces in Kosovo and has been established in 1952. The cultural objects exhibited belong to the Neolithic, Bronze, Iron, Roman, Byzantine and Middle Age periods; and the Multimedia sector contains equipment and digital materials, illustrating the historical and material heritage. It is a plastic demonstration of the historical richness of its social environment: a complex, united city, with a huge texture of sociality, youth and culture, and a constitutive multicultural environment [13].

Peace-oriented museums as carriers of hope and coexistence

Museums, especially peace-oriented museums, have an irreplaceable social and cultural dimension, as places for education and, specifically, place-based education, within which it’s possible to develop educational programs with a transdisciplinary approach, based on three core values: environmental awareness, cultural echoes, and global resonance [14]. This approach can be addressed in both ways: they bring, through the items they show, the past into the present and towards the future; and they dialogue with the context where they are and with the places of culture and memory of the city.

While, in Belgrade, the presence of two museums with a specific vocation «against war and for peace», such as the Museum of Yugoslavia and the Museum of African Art, can be considered well known to national and international public, in Sarajevo another museum of similar value deserve specific attention, the Olympic Museum, echoing the 1984 Winter Olympic Games.

The Museum of Yugoslavia is housed in the masterpiece modernist-style building designed by the architect Mihajlo Janković (1962) and is organized as an “open museum”, a place for research and dialogue, to encourage a culture of memory on the liberation movement and the post-war socialist Yugoslavia, and also the development of the Yugoslav idea in the 20th century. It is structured through galleries and open spaces and develops exhibitions, projects and educational programs [15] (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10: The Museum of Yugoslavia, Belgrade, ph. by Gianmarco Pisa.

The Museum of African Art in Belgrade is the first museum in the Yugoslav region entirely devoted to the cultures and arts of Africa, with the aim to realize an “anti-colonial museum”. It is hosted in a modernist-style building, designed by the architect Slobodan Ilić (1977), in the form of a one-storey structure which symbolically represent the connection between the anti-colonial nature of its concept and the internationalist idea of friendship among peoples brought by the Non-Aligned Movement [16].

The Olympic Museum, in Sarajevo, is a portrait of the history of Yugoslavia at the crossroads of the 1980s and the Olympic values. It is the only Olympic museum in the post-Yugoslav region and plays an important role as a cultural place for culture and peace education, since, as its presentation recalls, «the basic concept of the Olympic Museum is to present the spirit of “Olympism”, the Olympic values, creativity, youth, peace and other positive achievements through sports and art» [17].

The powerful inspiration of artistic practice and peace building

These museums represent a vivid testimony to the potential the link between «art and society» and, particularly, artistic expression and peace building, can convey. As the arts can help people question themselves, reflect, change their ideas and perception of the world, so peacebuilding, as a work on the causes of conflict to transcend the conflict itself, engages people to act for social transformation. Both the arts and peacebuilding concern the image of the society you want to shape, the glance through which social relations are observed, and the potential to transform those relations [18].

In such museums, three essential features can be identified: the display of artistic contents able to convey a cultural memory and to dialogue with the contradictions of the present time, driving a reflection about «history and memory in the public space»; the setting up of exhibitions to start a reflection on the past, the present time, and the future, about war, democracy, and peacebuilding; and, last but not least, the arrangement of educational events and initiatives, activities and projects.

In a conflict dynamics, when the relationships between the parties appear frozen and the problems seem insurmountable, artistic expression can help to unlock the crystallized positions, to modify the perception and the judgment on facts and circumstances, to fuel the necessary creativity to identify positive solutions. Peace efforts can find in the museums, as places of culture and participation, a powerful vehicle for place-based education, for violence prevention and peace building [19].

While intentionally enucleating, through the aesthetic formulation, a programmatic content, each of these transfers a myth and conveys an ideal, from the fight for freedom and coexistence, to a vision of solidarity and peace. They are memorial functions in public space, carriers of hope, and, ultimately, active places of memory, since: «Forgotten things are like those that have never existed» [20].

[1] Maurice Halbwachs (1925), I quadri sociali della memoria, Ipermedium, Naples, 1997, p. 23.

[2] Eviatar Zerubavel, Mappe del tempo. Memoria collettiva e costruzione sociale del passato, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2005, p. 29.

[3] Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Zakhòr. Storia ebraica e memoria ebraica, Giuntina, Florence, 2004, § III e § I.

[4] Sanja Horvatinčić, “Monument, Territory, and the Mediation of War Memory in Social Yugoslavia”, Zivot Umjetnosti, 2015, pp. 32-59.

[5] Vladana Putnik Prica, “12,000 Monuments (and Nothin’ on Map)”, Remembering Yugoslavia Podcast: https://rememberingyugoslavia.com/podcast-vladana-putnik-prica.

[6] Cfr. the Declaration and Program of Action on a Culture of Peace (A/53/243), UN General Assembly, 06 October 1999: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/53/243.

[7] Dejan Djokić, “Whose Myth? Which Nation? The Serbian Kosovo Myth Revisited”, in Janos Bak, Jörg Jarnut, Pierre Monnet, Bernd Schneidmueller (eds.), Uses and Abuses of the Middle Ages: 19th – 21st Century, Wilhelm Fink, München, 2009.

[8] “At Kosovo’s national stadium, we’re outed as Not Ultras”, retiredmartinblog, 11 April 2023: https://retiredmartin.com/2023/04/11/at-kosovos-national-stadium-were-outed-as-not-ultras.

[9] H.E.R.M.E.S. project website is available at the link: https://corpicivilidipace.com.

[10] The Association’s library is available online: https://www.reteccp.org/biblioteca/titoli/biblioteca.html.

[11] Vesa Sahatciu, “Monuments without a home”, Kosovo 2.0 Magazine, 03 June 2013, online: https://kosovotwopointzero.com/en/monuments-without-a-home.

[12] The presentation of the Sevdah Art House, Sarajevo, is online: https://sevdalinka.info/en/sevdah-art-house-2.

[13] The presentation of the Museum of Mitrovica, Kosovo, is online: https://mitrovicaguide.com/place/museum-of-modern-art.

[14] Sudiyasa, “Place-Based Education: Local Wisdom for Global Insights”, Medium Magazine, 17 October 2023: https://medium.com/@sudiyasa/place-based-education-local-wisdom-and-global-insights-8f58264dbf97.

[15] The presentation of the Museum of Yugoslavia, Belgrade, is online: https://muzej-jugoslavije.org.

[16] The presentation of the Museum of African Art, Belgrade, is online: https://mau.rs/en.

[17] The presentation of the Olympic Museum, Sarajevo, is online: https://okbih.ba/en/text/olympic-museum/76.

[18] Kyoko Okumoto, “The Arts-based Approach in Peace Work: Dynamic Peace and Dynamic Art”, Transcend Media Service, 8 May 2017: https://www.transcend.org/tms/2017/05/the-arts-based-approach-in-peace-work-dynamic-peace-and-dynamic-art-2016.

[19] Lisa Schirch, Michael Shank, “Strategic Arts-Based Peacebuilding”, Peace and Change, v. 33, n. 2, April 2008, pp. 217-242: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2008.00490.x.

[20] Giuseppe Leo (ed.), Id-Entità Mediterranee. Psicoanalisi e luoghi della memoria, Frenis Zero, Lecce, 2010, p. 133.

Djukanović Z., Bobić A., Apostolović M., Mihajlović B., Djerić A., Vasiljković V. (eds.), Umetnost u javnom prostoru – Art in Public Space, Avangarda, Belgrade 2011.

Halbwachs M. (1925), I quadri sociali della memoria, Ipermedium, Naples, 1997.

Iveković R., La balcanizzazione della ragione, Manifestolibri, Rome, 1995.

Lehrer E., Milton C. E., Patterson M. E. (eds.), Curating Difficult Knowledge, Violent Pasts in Public Places, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2011.

Leo G. (ed.), Id-Entità Mediterranee. Psicoanalisi e luoghi della memoria, Frenis Zero, Lecce, 2010.

Nora P., Les Lieux de Mémoire, Gallimard, Paris, 1984-1992.

Pisa G., Le porte dell’arte. I musei come luoghi della cultura tra educazione basata negli spazi e costruzione della pace – Art Doors. Museums as places of culture between place-based education and peace building, Multimage, Florence, 2024.

Vasiljević M. (ed.), Art as Resistance to Fascism, Catalogue of the Exhibition, Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade, 2015.

Yerushalmi Y. H., Zakhòr. Storia ebraica e memoria ebraica, Giuntina, Florence, 2004.

Zerubavel E., Mappe del tempo. Memoria collettiva e costruzione sociale del passato, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2005.

___________________________________________________

Naples, Italy, 2 Oct 2025 – International Day of Nonviolence

All hyperlinks have been verified as of today.

Gianmarco Pisa – Civilian peacekeeper engaged in action-research for conflict transformation in the frame of the Italian Peace Research Institute – Civil Peace Corps (IPRI-CCP) and active in peace projects in the W. Balkans and the international scenario. Member of the Peace Education working group in the frame of the Italian Network for Peace and Disarmament; corresponding member of the Maniscalco Centre – Heritage at Risk Research and Documentation Network; member of the Scientific Committee of the Civilian Defence Study Centre (CSDC), he is the author of publications on the topics of peacebuilding, culture and memory in social transformation processes.

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Balkans, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Conflict Mediation, Conflict Transformation, Conflict studies, Croatia, Eastern Europe, Kosovo, Nonviolence, Nonviolent Action, Peacekeeping, Yugoslavia

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 6 Oct 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Memories of the Future, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.