Hard-Line Buddhist Monks Threaten Burma’s Hopes for Democracy

ASIA--PACIFIC, 9 Nov 2015

Annie Gowen – The Washington Post

5 Nov 2015 – More than 10,000 Buddhist monks and nuns rallied recently to celebrate Burma’s restrictive new race and religion laws, packing themselves into an indoor soccer stadium to cheer and chant nationalist slogans.

Buddhist monks attend a Ma Ba Tha ceremony to mark the approval of race and religious laws at Thuwana indoor stadium in Rangoon on Oct. 4. (Lynn Bo Bo/EPA)

The event, held last month in Burma’s commercial capital, was a dramatic display of a rising force in Burma’s political landscape — a group of ultra-nationalist Buddhists called the Ma Ba Tha, whom analysts say could pose a threat to the country’s shaky hopes for democracy.

[Burma’s election the first ‘real test’ of shift toward democracy]

Voters in Burma, or Myanmar, head to the polls Sunday in a landmark election that is the first since the military junta eased their control and began democratic overhauls in 2010. Reliable polling is scarce, but Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s Nobel laureate, has been drawing large crowds as she campaigns across the country for her National League for Democracy party.

Meanwhile, leaders of the Ma Ba Tha, which translates to the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, have thrown their support to President Thein Sein, the former general, and his military-backed ruling party. The movement’s growing influence and its support for laws restricting religious freedom have troubled Burma’s advocates in the United States, who saw the country as a potential model for democratic overhauls and an Obama administration success story.

Tom Malinowski, assistant U.S. secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor, said there were two narratives in the election.

“There is the narrative of democracy vs. dictatorship and then a competing narrative which aims to convince voters this is an election about protecting the vast majority of Burmese who are Buddhists against what has been characterized as an existential threat from a tiny minority that is Muslim,” Malinowski said. “That gives rise to worries many people have about potential violence down the road. You can’t invent such a narrative for an election and then forget about it the day after.”

Ashin Wirathu, the firebrand Buddhist monk who is a leader in the Ma Ba Tha, said that the group is supporting Thein Sein because his government passed the legislation governing interfaith marriage, family size and religious conversion that many say targets the Muslim minority.

Buddhist monks take pictures with their phones during a gathering of nationalist monks and their supporters to celebrate four controversial bills, which recently became laws, in Rangoon on Oct. 4. (Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP)

“As President Thein Sein implemented the race and religion protection laws without caring about international pressure, we see him as a special one,” Wirathu said in an interview. If Suu Kyi and her party come to power, he said, Burma would have “female dictatorship.” Suu Kyi is technically barred from the presidency by a constitutional provision, but she has said she will lead the country anyway if her party wins a majority.

“The way she behaves, the way she treats the people inside the party and the audience, and the small parties, she has more percentage on the authoritarian side,” the monk said. “So, if she is in power, I can imagine that a female dictatorship country will emerge in the world.”

Ashin Wirathu, 47, is one of the Ma Ba Tha’s most outspoken advocates. He has called Muslims mad dogs and the United Nations envoy for human rights a “bitch” and a “whore.” He has been dubbed the “Burmese bin Laden,” a label he once rejected but says no longer troubles him.

“About the election,” he says. “Ma Ba Tha just hopes for security and peace.”

Burma, a predominantly Buddhist country of 51 million, was under military rule for more than a quarter-century until Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government released Suu Kyi from house arrest, freed other political prisoners and relaxed censorship. The actions paved the way for the United States and other countries to ease sanctions and resulted in millions in foreign investment.

Analysts say that lifting controls allowed some free speech for the first time in decades, but also permitted radical monks such as Ashin Wirathu to flourish on Facebook and elsewhere. Ashin Wirathu began advocating avoiding Muslim businesses as part of the “969 Movement,” a precursor to Ma Ba Tha.

[Burma’s half-hearted commitment to democracy]

Radical monks have been accused by human rights organizations of hate speech that fomented violence in Rakhine State in 2012, which left more than 200 dead and displaced more than a quarter-million. Many were the stateless Rohingya Muslims. About 140,000 Rohingya continue to live as virtual prisoners, ostensibly for their own safety, in fetid camps. They were stripped of voting rights earlier this year.

On a recent campaign swing through Rakhine State, Suu Kyi did not speak directly about the plight of the Rohingya but was peppered with questions from local Buddhists asking if Muslims would have greater power if her party ran the country. Her party has not fielded any Muslim candidates, in part to avoid criticism from the Ma Ba Tha.

“If we choose Muslim candidates, Ma Ba Tha points their fingers at us so we have to avoid it,” NLD leader Win Htein told UCA news, the Asian Catholic news agency.

Burmese Muslims who are citizens said they too had been subject to growing incidents of racism, saying that Buddhists refuse to patronize their stores and they have had trouble getting identity cards.

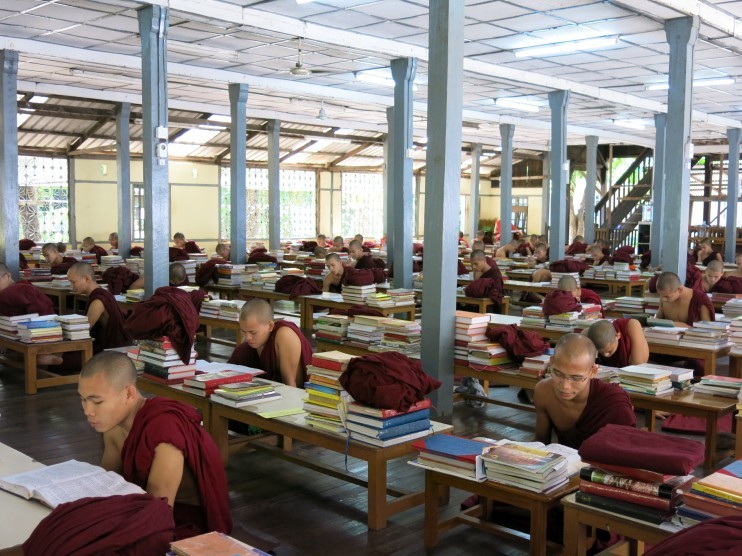

Monks study in a classroom at the headquarters of the Ma Ba Tha organization on Oct. 18. (Annie Gowen/The Washington Post)

Sandals outside a classroom at the headquarters of the Ma Ba Tha organization on Oct. 18. (Annie Gowen/The Washington Post)

Ashin Wirathu argues that the Buddhists are the targets.

“It is more than a threat, they are harming us physically,” he said, noting that in 2012 eight villages were destroyed in Rakhine and Buddhists were killed and attacked.

Observers say that the Ma Ba Tha has amassed grass-roots support, a broad donor base and increasingly tech-savvy volunteers since it was formed in 2013. Burmese scholar Maung Zarni said they are a puppet of the military, noting the impressive array of military men who showed up for the Oct. 4 rally.

Election observers for the Carter Center — the nonprofit public policy center founded by former president Jimmy Carter — also raised concerns about the rally and the “potentially disruptive use of nationalist and religious rhetoric during the campaign” in a recent report. The group has received four official complaints of misuse of religion in the campaign, including members of the Ma Ba Tha passing out materials that target candidates. Monks are technically prohibited from participating in political activities.

On a recent day, the headquarters for the Ma Ba Tha movement located in a monastery in Rangoon’s Insein Township was quiet, its nearby temple holding only a few worshipers of a large reclining Buddha. A pink-robed nun enthusiastically ushered guests into a small bookshop to show off a variety of nationalist tomes.

“We need these laws to safeguard our own race and religion. Buddhism has almost been swallowed completely around the country,” the nun, Khay Mar Thi, said.

A gong sounded, and dozens of monks emerged on their way to afternoon study. Some said they didn’t know much about this group in their midst; others said they didn’t want to talk. But a few were only too happy to share what they had learned.

“Muslims are dangerous,” said novice monk Shin Thu Mana. “They’re not like other religions.”

___________________________________

Read more:

Some in Burma still don’t know if they can vote in historic election

Burma, once a pariah state, gets its first taste of KFC

The serene-looking Buddhist monk accused of inciting Burma’s sectarian violence

Annie Gowen is The Post’s India bureau chief and has reported for the Post throughout South Asia and the Middle East.

Go to Original – washingtonpost.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.