Earthland: Scenes from a Civilized Future

PARADIGM CHANGES, 20 Mar 2017

Paul Raskin | The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

This paper is one of many proposals for a systemic alternative we have published or will be publishing here at the Next System Project. We have commissioned these papers in order to facilitate an informed and comprehensive discussion of “new systems,” and as part of this effort we have also created a comparative framework which provides a basis for evaluating system proposals according to a common set of criteria.

Scenes from a Civilized Future

This essay is written as a dispatch from the future. We visit Earthland in 2084, the flourishing planetary civilization that has emerged out of the great crises and struggles that today still lie before us. We learn how decades earlier a “global citizens movement” had coalesced and gathered momentum, becoming the key agent of the Great Transition that bent the arc of history from catastrophe to renewal.

The fictive author is a veteran of the battle for the twenty-first century, and now an elder statesman of the new order. He celebrates how far the world has come, yet acknowledges that, struggling to heal past wounds and invent a viable future, Earthland is no utopia. Still, its humanistic and ecological values, its ethos of balance between globalism and pluralism, and its enlightened economic and political system fill him with hope. He could be your grandchild or child; or, young Earthlander, might he be you?

This essay is an excerpt from Journey to Earthland: The Great Transition to Planetary Civilization, a new book that builds a framework for understanding and shaping our world in transition. The book’s initial sections provide essential context and motivation for the visionary “destination” presented here as a stand-alone piece. The point of departure is the recognition that history has entered the Planetary Phase of Civilization. As strands of interdependence weave humanity and Earth into the overarching proto-country of Earthland, social evolution will play out on a world stage where perils are many and the outcome uncertain and contested.

Journey to Earthland introduces a simple “taxonomy of the future” to help organize thinking about global scenarios. At the highest level, three broad channels fan out from the unsettled present into the imagined future: worlds of incremental adjustment (Conventional Worlds), worlds of calamitous discontinuity (Barbarization), and worlds of progressive transformation (Great Transitions). The book explores different variations for each prong of this archetypal triad of evolution, decline, and progression.

Conventional Worlds evolve with no fundamental shift in the prevailing social paradigm or structure of the world system. Episodic setbacks notwithstanding, persistent tendencies—corporate globalization, the spread of dominant values, and poor-country emulation of rich-country production and consumption patterns—are assumed to drive the regnant model forward. But Barbarization scenarios, the evil cousins of Conventional Worlds, all the while feed on unattended crises. In these futures, a deluge of instability—social polarization, geopolitical conflict, environmental degradation, economic failure, and the rampaging macro-crisis of climate change—swamps the corrective mechanisms of free markets and government policy. A systemic global crisis thereby spirals out of control as civilized norms dissolve.

Great Transitions imagine how the powerful exigencies and novel opportunities of the Planetary Phase might advance more enlightened aspirations. An ascendant suite of values—human solidarity, quality of life, and an ecological sensibility—counters the conventional trio of individualism, consumerism, and domination of nature. This shift in consciousness underpins a corresponding shift in institutions, toward democratic global governance, economies geared to the well-being of all, and sound environmental stewardship.

Is there a path to a decent, resilient civilization within a Conventional Worlds framework? When they proffer small-bore correctives, opinion shapers and decision-makers implicitly assume so. Whether they realize it or not, they are, in the name of prudence, gambling that mega-crises will not overwhelm gradual market and policy responses. Neoliberal reliance on maximally free markets is an especially quixotic and therefore deeply irresponsible creed. Capitalism’s tendencies to exploit people, concentrate wealth, and lay waste to nature drive the contemporary crisis; and prescribing more of the same would only further bleed the patient.

Recognizing the dangers, legions of reformers champion the reassertion of governance authority to tame corporate capitalism and steer it toward sustainability. Despite their best efforts, systemic deterioration has outpaced piecemeal efforts to make the conventional development paradigm greener and fairer. Tacking against the mighty winds of a dysfunctional system, reform can take us only so far, akin to trying to climb up a down escalator. Rather than helping, the machinery—profit motive, corporate power, consumerist values, state-centric politics—pushes in the opposite direction.

Who speaks for Earthland? We can hardly expect the entrenched institutions of the current order—corporations, governments, large civil society organizations—to be at the forefront of efforts to supersede it. With deep stakes in maintaining the status quo, they are too timorous and too venal to address profound environmental and social problems. They would be as miscast for a revolutionary role as would have been the feudal aristocracy in leading the charge to modernity. We need to look elsewhere for a leading actor.

Hope rests with the cosmopolitan taproots sprouting in the crumbling foundations of the Modern Era. The fundamental condition of the Planetary Phase—shared risks and a common fate—urges collective responses that transcend fractious political arrangements and truncated social visions. Augmented interdependence kindles modes of association and currents of thought attuned to the superordinate configuration of Earthland (at the same time breeding the social pathologies of Barbarization).

Reaching Earthland will take a global citizens movement as vast, plural, and multi-scale as the crisis that spawns it and the vision that beckons it. Can it take shape at the requisite speed, scale, and coherence? The race for the soul of Earthland is on. Disturbing omens abound, yet spreading awareness and broadening engagement hint that a systemic movement may be gestating. The question becomes how to help bring it into the world and give it life.

If the global movement matures as the systemic crisis deepens, a Great Transition could rapidly unfold in a whirlwind of change. As dominant norms lose their sway, and institutional structures begin to crack, the revolutionary moment will have arrived. If well prepared, oppositional and visionary movements can influence the anatomy of the world that emerges from the tumult. Then we could reach the kind of civilized destination envisioned here.

Mandela City, 2084

Let us pause, in this centennial of George Orwell’s nightmare year, to remember where we have been and reflect on where we are on the long arc of the Great Transition. This brief treatise considers the state of planetary civilization today, sketching its complex structure, social dynamism, and unfinished promise—and, yes, celebrating how far we have come. The portrayal may strike some readers as overly burnished, but this author, a proud veteran of the battle for the twenty-first century, makes no apology. He cannot claim neutrality, yet has no illusions: we live in Earthland—not Shangri-La—where real people confront real problems. Still, who would deny that the world today stands as living refutation of the apocalyptic premonitions that once haunted dreams of the future?

One Hundred Years that Shook the World

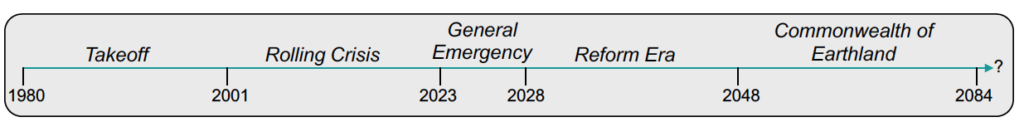

Our snapshot of 2084 can glimpse only a single frame in the moving picture of twenty-first-century history. That history, already the subject of an ocean of literature plumbing the roots and meaning of the Great Transition, is swelled daily by new discoveries, interpretations, and controversies. Rather than add more foam to that rising tide, a potted history will suffice here for locating the contemporary world in the context of the unfolding transition. The “five stage theory” introduced in the seminal chronicle One Hundred Years That Shook the World offers a useful framework.

Major Stages of the Great Transition:

Takeoff of the Planetary Phase (1980–2001). A unitary social-ecological global system began to crystallize, signaling the onset of a major new epoch. This holistic phenomenon found multiple expressions, among them economic globalization, biospheric disruption, digital connectivity, transnational civil society, and global terrorism. The formation of an interdependent configuration accelerated after the collapse of the bipolar Cold War order in 1989, as global capitalism gained hegemony, lubricated by “Washington Consensus” policies of deregulation, free trade, privatization, and retrenchment of government services. In response, massive protests erupted at intergovernmental meetings, but they could only slow,not reverse, the juggernaut of corporate-led globalization. In parallel, burgeoning cross-border marketing and entertainment industries spurred consumerism among the affluent, yearning among the have-nots, and thwarted expectations among the young and angry. A dissonant cacophony-dot-com bubbles bursting, towers crashing, dogs of war barking, glaciers collapsing—rang in the new millennium, shattering dreams of market utopia.

Rolling Crisis (2001–2023). Freewheeling turbo-capitalism segued into an unrelenting drumbeat of war, violence, displacement, pandemic, recession, and environmental disruption. The rat-a-tat of bad news, at first experienced as discrete developments, came to be understood instead as deeply connected: distinct manifestations of a comprehensive structural crisis. Correspondingly, critiques grew more systemic and radical, individual angst spread, and collective resistance gathered momentum. As the crisis surged, the “global citizens movement” (GCM) convened its inaugural Intercontinental Congress in 2021, where it adopted the landmark Declaration of Interdependence, the eloquent manifesto that captured the growing consensus on the “character of the historic challenge,” “principles of unity,” and “visions of Earthland.”1 The GCM’s message spread virally through a vast lattice of affiliated nodes, spawning circles of engagement across the planet. The movement became a living socio-political experiment in creating an Earthlandic community, with each jolt of the Rolling Crisis galvanizing new adherents and enhancing its clout. By 2023, movement “circles” were ubiquitous, advancing local strategies linked to the wider shift. The popular rising came too late to reverse the global tailspin, but without it, the future surely would have been far bleaker.

General Emergency (2023–2028). The multipronged crisis rolled on, gathering into a mighty chain reaction of cascading feedbacks and amplifications. Every cause was an effect, every effect a cause, with the hydra-headed impacts of climate change at the swirling vortex of systemic distress. The poor suffered most acutely, though no one could fully insulate themselves from the cauldron of disruption. This was a tragic period by any measure, yet could have been even worse had the world not mobilized in response. The GCM, its strength surging, played a critical role by prodding befogged and irresolute governments into acting on the comprehensive sustainability and climate goals that had languished since the UN adopted them in 2015. This Policy Reform mobilization quelled the chaos and thwarted the New Earth Order (NEO), an elite alliance preparing to proclaim an emergency World Authority. Ironically, the authoritarian NEO threat triggered a massive public reaction that further fueled the GCM and the politics of deep reform. The world pulled back from the brink, leaving the “NEOs” ample time to ponder their mis-calculations during their long years of incarceration.

The Reform Era (2028–2048). As the upheaval abated, the old order began to reassert itself. But the generation of leaders that came of age in the throes of crisis were well-schooled in the mistakes of the past, and understood the necessity for strong government stewardship, lest history repeat itself. The UN established the New Global Deal (NGD), the apotheosis of enlightened international governance, which included a hard-hitting ensemble of policies, institutions, and financing to deliver on the aspirational goals of the old sustainability agenda. At the heart of the NGD was the push for “resilience economies” that would channel and constrain markets to function within more compassionate social norms and well-established environmental limits. Over the vehement objection of its impatient radical wing, the GCM put its considerable political weight behind this defanging of free-market capitalism, deeming “planetary social democracy” a necessary way station on the path of Great Transition. However, by the 2040s, Policy Reform’s “alliance of necessity” became untenable: retrogressive forces, stoked by well-funded revanchist campaigns, grew stronger, and the old pathologies of aggressive capitalism, consumerist culture, and xenophobic nationalism recrudesced. Progressives everywhere anxiously asked, is reform enough? The answer resounded across the continents: “Earthland Now!” The GCM was prepared, harnessing discontent into effective strategy, and gaining decisive political influence in a growing roster of countries and international bodies. The movement’s internal deliberative body, the Earthland Parliamentary Assembly (EPA), was repurposed as the core body for democratic global governance.

Commonwealth of Earthland (2048–present). The current stage of the Great Transition began when the EPA adopted by consensus the World Constitution of 2048 (see more on the constitution below), formally establishing the Commonwealth of Earthland. Resistance flared among sectoral interests and nativist bases, but in response, masses of ordinary people mobilized to defend the Commonwealth. After a tumultuous decade, the new institutional structures began to stabilize on the road to a civita humana. The revolutionary turn toward planetary civilization was in full swing.

What Matters

All along, the tangible political and cultural expressions of the Great Transition were rooted in a parallel transition underway in the intangible realm of the human heart. People returned to the most fundamental questions: How shall we live? Who should we be? What matters? The collective grappling for fresh answers provided the moral compass for the journey through the maelstrom of planetary change.

Now, the entire edifice of contemporary civilization rises on a foundation of compelling human values. The prevailing pre-transition ethos—consumerism, individualism, and anthropocentrism—has yielded to a different triad: quality of life, human solidarity, and ecocentrism. These values spring from a sense of, and a yearning for, wholeness as individuals, as a species, and as a community of life. To be sure, our diverse regions and cultures invest these values with unique shades of meaning and varying weights. But they remain the sine qua non nearly everywhere.

The enhancement of the “quality of life,” rather than the old obsession with GDP and the mere quantitative expansion of goods and services, has come to be widely understood as the only valid basis for development. This conviction now seems so self-evident that there is a danger of losing sight of its historical significance. It must be remembered how over the eons, the problem of scarcity and survival—what Keynes called the “economic problem”—had dominated existence. Then, the industrial cornucopia opened the way, at least in principle, to a post-scarcity civilization, but the dream was long deferred as deeply inscribed class divisions brought, not decent livelihoods for all, but over-consumption for the privileged and deprivation for the excluded. Now, the synergy of two factors—an ethic of material sufficiency (“enough is enough”) and an equitable distribution of wealth (“enough for all”)—has enabled ways of living more satisfying than the work-and-buy treadmill for the affluent and desperation for the economically marginal.Today, people are as ambitious as ever, but fulfillment, not wealth, is the primary measure of success and source of well-being.

The second pillar of the contemporary zeitgeist—human solidarity—bolsters the strong connection we feel toward strangers who live in distant places and descendants who will inhabit the distant future. This capacious camaraderie draws on wellsprings of empathy that lie deep in the human psyche, expressed in the Golden Rule that threads through the great religious traditions, and in the secular ideals of democracy, tolerance, respect, equality, and rights. This augmented solidarity is the correlative in consciousness of the interdependence in the external world. The Planetary Phase, in mingling the destinies of all, has stretched esprit de corps across space and time to embrace the whole human family, living and unborn, and beyond.

Ecocentrism, our third defining value, affirms humanity’s place in the web of life, and extends solidarity to our fellow creatures who share the planet’s fragile skin. We are mystified and horrified by the feckless indifference of earlier generations to the integrity of nature and its treasury of biodiversity. The lesson was hard won, and much has been lost, but the predatory motive of the past—the domination of nature—has been consigned to the dustbin of history. Rapacious no more, our relationship to the earth is tempered by humility, which comes with understanding our dependence on her resilience and bounty. People today hold deep reverence for the natural world, finding in it endless wonder, sustenance, and enjoyment.

One World

The enlarged sense of place has buoyed an ethos of globalism as strongly felt as nationalism once was, perhaps more so. After all, gazing down from orbital flights and space excursions, we behold an integral planet, not imaginary state boundaries. Social prophets had long envisioned one human family—“Mingle the kindred of the nations in the alchemy of love,” Aristophanes importuned— but the dream of One World had to await its unsentimental partner: mutual self-interest. The Planetary Phase ignited cosmopolitan aspirations, meshing them with the exigency for cooperation in a world of shared risks. The subjective ideal was now anchored in objective conditions.

Thus, it has become axiomatic that the globe is the natural political unit for managing common affairs: sustaining the biosphere and keeping the peace, of course, but also cultivating an organic planetary civilization in its many dimensions. Indeed, Earthland’s thriving world culture and demos stand as the apotheoses of the transformation. At least that would be the view of the graying generations of the Great Transition, if not of the restless youth who, taking the Commonwealth for granted, look for new frontiers of transformation in space colonization (and certainly not for the fringe Eco-communal parties that indulge the rhetoric of Balkanization).

The quartet of principles underpinning our global political community has roots in the great struggles of our forebears for rights, peace, development, and environment. The 2048 World Constitution builds on this indispensable heritage, codified in milestone agreements such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1992 Earth Summit’s Agenda 21, and the 2000 Earth Charter. Its preamble draws heavily from the GCM’s 2021 Declaration of Interdependence, with its call for an Earthland of rights, freedom, and dignity for all within a vibrant and sustainable world commonwealth.

These unifying principles would have remained little more than good intentions were they not rooted in the commitment of living human beings. Ultimately, the keenly felt sense of solidarity with people and the larger living world binds and sustains our planetary society. The global citizens of today have in practice absolved the old visionaries and dreamers of a new consciousness: “Let us think of the entire earth and pound the table with love” (Pablo Neruda).

Many Places

This resolute commitment to One World is matched by an equal commitment to Many Places. The celebration of both unity and diversity animates our “politics of trust” with its two prongs: the toleration of proximate differences and the cultivation of ultimate solidarity. The transformation has demonstrated that the tension between globalism and localism, although very real, need not be antagonistic. Indeed, the two sentiments are dialectically linked, mutual preconditions for a stable and flourishing political culture. On the one hand, the integrity of One World depends on vibrant regions for cultural innovation, community cohesion, and democratic renewal. On the other, the vitality of Many Places depends on the global political community to secure and enrich our shared civilization and planet.

A century ago, it was common to speak of a unitary project of “modernity” in which all nations would eventually replicate the institutions, norms, and values of advanced industrial societies. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, some scholars went so far as to proclaim the “end of history,” the final phase of the modernist project. Although self-serving and ahistorical, the theory (and ideology) that all countries would converge toward the dominant model contained a kernel of truth. Capitalism’s expansionary logic sought to incorporate peripheries and transform them in its own image. At least, that is, to the degree it was given free rein.

We are regional denizens with allegiance to place, and also global citizens building a world community.

The crisis of the world system put the final nails in the coffin of such historical determinism, exposing it as the convenient conceit of imperial ambition in a hegemonic era. In our time, the Commonwealth is confirming on the ground the counterproposition—that multiple paths to modernity are available—long posited by oppositional thinkers. Today, the paramount ideals of modernity— equality, tolerance, reason, rule of law, and active citizenship—are ubiquitous, but find sundry expression across a variegated social landscape.

The fabric of our global society is a stunning tapestry woven of hundreds of distinct places. Many of Earthland’s regions took shape around existing national boundaries or metropolitan centers, some traced the perimeters of river basins or other “bioregions,” and a few had been semi-autonomous areas within old nation-states.2

They come in all sizes and varieties from shall, homogenous communities, to large, complex territories, themselves laced with semi-autonomous sub-regions.

The consolidation of Earthland’s regional map over the past several decades was not without conflict. Social tensions and land disputes were inevitable, some flaring around stubborn boundary controversies inherited from the past, and some engendered by more porous borders, as global citizenship liberalized the right to resettle. Aided by the simple alchemy of time that turns yesterday’s strangers into today’s neighbors, and assuaged by the Commonwealth’s persuasive mediation and financial inducements, our constellation of regions has largely stabilized. Sadly, though, lingering discord in a handful of hotspots remains a painful sore on the body politic, and a protracted challenge for World Court adjudications.

What is the character of Earthland’s regions? Although an exhaustive survey is beyond the remit of this monograph, it is useful to organize the kaleidoscope of places into a manageable taxonomy of social forms. A world traveler today is likely to encounter three types of regions, referred to here as Agoria, Ecodemia, and Arcadia. These whimsical coinages rely on Greek roots to evoke the classical ideal of a political community—active citizens, shared purpose, and just social relations—that inspires all our regions.

In ancient Athens, the agora served as both marketplace and center of political life; thus, commerce and consumption figure prominently in Agoria. The neologism Ecodemia is a portmanteau combining the word roots of economy and democracy; thus, economic democracy is a priority in these regions. Arcadia was the bucolic place of Greek myth; thus, the local community and simpler lifestyles are particularly valued here.

It should be underscored that this trinity of regional types is intended to provide a broad-brush map of Earthland’s places. A more granular examination would reveal the enumerable ways actual regions deviate from these idealizations. Furthermore, larger regions, rather than being homogenous, often contain sub-regions that vary from the dominant pattern (a striking example is the Arcadian northwestern district of Agorian North America). And one final caveat: our tidy typology excludes the few volatile zones yet to establish a stable regional identity.

Still, the three archetypes capture distinctions critical for understanding Earthland’s plural geographic structure. Agoria, with its more conventional lifestyle and institutions, would be most recognizable to a visitor from the past (indeed, some radical critics disparage these regions, mischievously referring to them as “Sweden Supreme”). Ecodemia, with its collectivist ethos and socialized political economy, departs most fundamentally from classical capitalism. Arcadia accentuates self-reliant economies, small enterprises, face-to-face democracy, frugality, and reverence for tradition and nature. In fact, all are late twenty-first-century social inventions unique to our singular time.

The reactionary Restoration Institute would beg to disagree. Its recent diatribe, The Great Imposition, argues that the Commonwealth of Earthland lacks historical legitimacy, claiming that our regions are mere perversions of the three great political “isms” of the past: capitalism, socialism, and anarchism. Not surprisingly, this facile provocation has been roundly lambasted in the popular media and excoriated by a small army of scholars. The blowback is well deserved, but give the devil his due: the Institute’s thesis contains a grain of truth. After all, Agoria’s market emphasis does gives it a capitalist tonality, Ecodemia’s insistence on the primacy of social ownership echoes classical socialism, and Arcadia’s small-is-beautiful enthusiasm channels the essence of the humanistic anarchist tradition.

However, these ideological associations mask as much as they reveal. Agoria’s dedication to sustainability, justice, and global solidarity is of a different order than the most outstanding social democracies of the past (“SwedenX10” to Agorian enthusiasts). Ecodemia’s commitment to democracy, rights, and the environment bears little resemblance to the autocratic socialist experiments of the twentieth century. Arcadia’s highly sophisticated societies are enthusiastic participants in world affairs, not the simple, pastoral utopias of the old anarchist dreamers.

Regional diversity reflects Earthland’s freedom and is essential for its cultural vitality. But the stress on difference should be balanced by a reminder of shared features. Compared to nations of a century ago, nearly all regions are socially cohesive and well-governed. All offer citizens a healthy environment, universal education and healthcare, and material security as a basis for the pursuit of fulfilling lives. Almost all are at peace. Most importantly, One World binds the Many Places as a planetary civilization. We are regional denizens with allegiance to place, and also global citizens building a world community. The exhilarating experiment gives Socrates’s prophetic hope a living form: “I am a citizen, not of Agoria, or Ecodemia, or Arcadia.”

Governance: The Principle of Constrained Pluralism

Of course, the harmonious ideal of One World, Many Places must inevitably alight in the discordant reality of contentious politics. The Commonwealth’s greatest quandary has been to fashion workable arrangements for balancing the contending imperatives of global responsibility and regional autonomy. In the early decades of the Planetary Phase, the political debate on this question, even within progressive circles, split along old dualities: cosmopolitanism versus communalism, statism versus anarchism, and top-down versus bottom-up. The solution for overcoming these polarities was remarkably simple, but difficult to see through the nationalist mystifications of the Cold War, the Time of the Hegemon, the Rolling Crisis, and the Reform Era.

Earthland’s political philosophy rests on the principle of constrained pluralism, comprised of three complementary sub-principles: irreducibility, subsidiarity, and heterogeneity. Irreducibility affirms One World: the adjudication of certain issues necessarily and properly is retained at the global level of governance. Subsidiarity asserts the centrality of Many Places: the scope of irreducible global authority is sharply limited and decision-making is guided to the most local level feasible. Heterogeneity grants regions the right to pursue forms of social evolution consonant with democratically determined values and traditions, constrained only by their obligation to conform to globally mandated responsibilities.

The principles of constrained pluralism are enshrined in the World Constitution, and few find them objectionable. However, philosophical consent can mask ideological devils that lurk in the details. The application of the framework in the political sphere has been a battleground of public contestation (almost always peaceful). The most controversial question—What should be considered irreducibly global?—has provoked a tug-of-war between contending camps advocating for either a more tight-knit world state or a more decentralized federation.

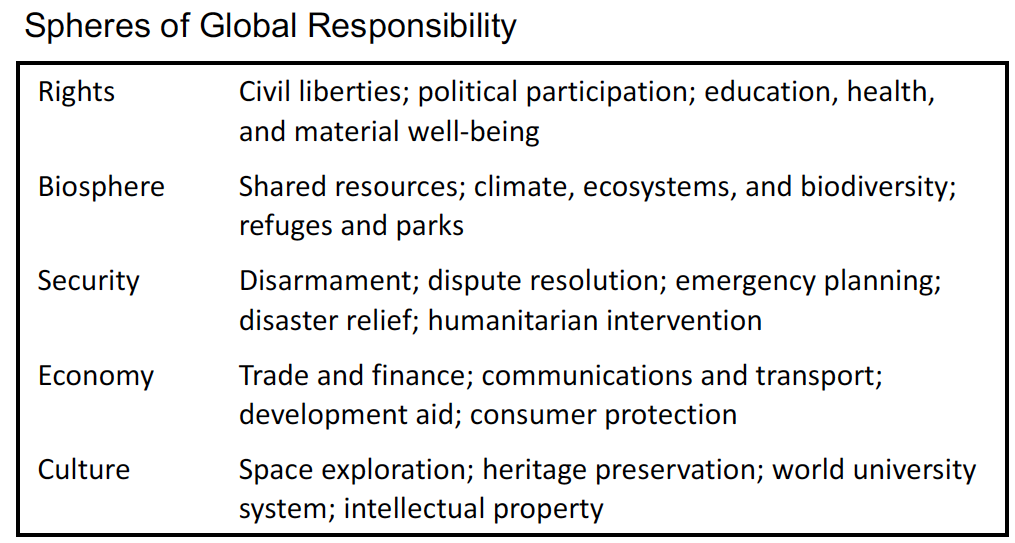

The debate on the proper balance between One World and Many Places has not abated, indeed, may never find resolution. Nevertheless, a wide consensus has been established on a minimal set of legitimate, universal concerns that cannot be effectively delegated to regions. The irreducible “Spheres of Global Responsibility” are summarized in the following chart. Spheres of Global Responsibility

Constrained pluralism is the concrete political expression of the old slogan “unity in diversity.” The commitment to unity implies that the planetary governance sets “boundary conditions” on regional activity to ensure the congruence of aggregate outcomes and global goals. The commitment to diversity bars central authorities from dictating how these conditions are met, leaving wide scope for regions to adopt diverse approaches compatible with cultural traditions, value preferences, and local resources. In turn, each region contains a hierarchy of sub-regional entities, nested like Russian matryoshka dolls from provinces down to hamlets;the principle of constrained pluralism applies at each level. Up and down the line, our political system delegates decision-making to the most local level possible, retaining authority at larger levels where necessary.

In the environmental realm, the Commonwealth’s regulation of greenhouse gas emissions illustrates the way the principle of constrained pluralism works in action. Total emissions are capped globally and allocated to regions in proportion to population; regional policies for meeting these obligations may accentuate market mechanisms, regulation, technological innovation, or lifestyle changes. Examples abound in the social sphere as well. For instance, the “right to a decent standard of living for all” provision of the World Constitution is universally applicable, operationalized globally as a set of minimum targets, then implemented regionally through such diverse strategies as ensured employment, welfare programs, and guaranteed minimum income. Finally, to take a sub-global example, river basin authorities set water quality standards and water withdrawal constraints, portioning obligations to riverine communities that in turn respond with locally determined strategies and policies.

All decision-making processes reflect the Commonwealth’s core governance principles of democracy, participation, and transparency; any politician tempted 2to bend the rules can expect to be held accountable by a vigilant public. Outside officialdom, civil society networks assiduously work to educate citizens, influence decision-makers, and monitor business practices and governmental behavior—and, when necessary, organize protests. And of course, the GCM did not vanish after the glory days of 2048. The movement remains a potent force for challenging the status quo and prodding change, to the chagrin of its many detractors, who deem its radical idealism an atavistic nuisance.

The World Assembly sits at the pinnacle of the formal political structure. Its membership includes both regional representatives and at-large members selected by popular vote in world-wide elections. At-large representation gives voice to “one world” politics by stimulating the formation of world parties as a counterweight to regional parochialism. Strong regional representation ensures that the “many places” are not forgotten. Together they constitute an effective safeguard against tyranny from above or below.

Within regions, the forms of democracy vary, including the representational systems typical of Agoria, the workplace nodes prominent in Ecodemia, and direct engagement in Arcadia. At the local level, face-to-face or virtual town hall meetings are the norm. Ultimately, Earthland’s vitality and legitimacy comes from the informed involvement of ordinary people, a goal mightily enabled by advanced communication technology that shrinks psychic space between polities and dissolves language barriers. The physical principle at the foundation of modern cyberspace—quantum entanglement—echoes the political entanglement of the global demos.

Economy

The size of the world economy has quadrupled since the early years of this century, and average income has tripled. In itself, this growth in the economic pie would be nothing to crow about because, all else equal, greater output correlates with greater environmental damage. What is worth celebrating is that the pie became more equally shared as income distributions tightened both between and within regions. Everyone has the right to a basic standard of living, and absolute destitution has been nearly eradicated, with the very few exceptions found in vanishing pockets of dysfunction.

The material well-being of the typical world citizen today is far higher than it was at the turn of the century, when Earthland was a failed proto-state inhabited by an obscenely wealthy few and impoverished billions. True, in certain places, like the North American region, average income is somewhat lower than it once was. However, the comparison is misleading in two important ways. First, in those days, average income was elevated by the bygone class of super-rich. Second, old GDPs were bloated by market transactions (“exchange value”) that did not contribute to human well-being (“use value”), such as expenditures on the military, environmental cleanup, and personal security. Correcting for these factors, the real income of a typical family has actually increased slightly.

More generally, the size of the market (GDP) was always a poor proxy for a society’s well-being, although that disconnect hardly deterred pre-Commonwealth politicians from making growth the be-all and end-all of public policy. By contrast, our comprehensive metrics of development, such as the widely employed QDI (Quality of Development Index), synthesize multiple dimensions of the human condition. Naturally, the economic standard of living still matters, but so do environmental quality,community cohesion, democratic participation, and human rights, health, and happiness. Holistic measures confirm quantitatively what everyday life tells us intuitively:

the state of world development has never been higher and continues to climb.

Zooming down to the regional scale provides a more textured view of the variety of economic arrangements. In Agoria, private corporations continue to play a major role, and investment capital for the most part is still privately held. But long ago, corporations have been rechartered to put social purpose at the core of their missions and to require the meaningful participation of all stakeholders in their decision-making. Moreover, they operate in a comprehensive regulatory framework designed to align business behavior with social goals, stimulate ecological technology, and nudge households to moderate consumerism. Supported by popular values, governments channel Agoria’s market economies toward building equitable, responsible, and environmental societies. Radical social democracy works and works well. (Full disclosure: the author resides contentedly in an Agorian precinct.)

Ecodemia’s system of “economic democracy” takes protean forms as it mutates and evolves in distinct cultural and political settings. The common feature is the expulsion of the capitalist from two key arenas of economic life: firm ownership and capital investment. Large-scale corporations based on private owners and hired employees have been replaced by worker- and community-owned enterprises, complemented by nonprofits and highly regulated small businesses. In parallel, socialized investment processes have displaced private capital markets. Publicly controlled regional and community investment banks determine how to recycle social savings and tax-generated capital funds, and rely on decision-making processes that include ample opportunity for civil society participation. These banks are mandated to review proposals from capital-seeking entrepreneurs, and to make approval subject to a demonstration that the projects are financially viable and advance society’s larger social and environmental goals.

Small privately held enterprises comprise the backbone of Arcadia’s relatively independent economies. But even in the land of small-is-beautiful, natural monopolies like utilities, ports, and mass transport are big-is-necessary exceptions. Place-based in spirit, Arcadia actively participates in world affairs and cosmopolitan culture. Some regions boast world-class centers of innovation in human-scale technologies: small-farm ecological agriculture, modular solar devices, human-scale transport systems, and much more. Churning with artistic intensity, Arcadia adds more than its share to Earthland’s cultural richness.

Whatever the regional economic architecture, a common principle guides policy: economies are a means for attaining social and environmental ends, not an end in themselves.

Exports of niche products and services, along with eco-tourism, support the modest trade requirements of these relatively time-rich, slow-moving societies.

So far, we have underscored the important role played by corporations in Agoria, worker-owned cooperatives in Ecodemia, and artisanal establishments in Arcadia. But rather than a single model, the forms of enterprise have proliferated in all regions. Certainly, the organizational ecology has become far more diverse than when huge corporations were dominant. In particular, the number and significance of nonprofit entities has continued to surge (particularly in Ecodemia and Arcadia but also in Agoria), reflecting people’s desire for purposive work and a “corporate culture” rooted in a social mission.

And let us not forget the labor-intensive “people’s economy” that flourishes alongside the high-technology base, producing a breath-taking array of aesthetic goods and skilled services. This informal marketplace supplements the incomes of many households, while offering artisans of a thousand stripes an outlet for creative expression. The people’s economy continues to be enabled and encouraged by social policies that promote “time affluence,” especially decreased work weeks and assured minimum income. Its role will surely grow in significance in the steady-state economy of the future as technological advance further reduces the labor requirements of the formal economy.

Whatever the regional economic architecture, a common principle guides policy: economies are a means for attaining social and environmental ends, not an end in themselves. Correspondingly, responsible business practices, codified in law and enforced by strong regulatory processes, are the norm for all enterprises. Approval of capital investments depends on a showing of compatibility with the common good, a determination made directly by public banks in Ecodemia or indirectly through the participatory regulatory and legal mechanisms in Agoria and Arcadia. Everywhere the application of the “polluter pays principle” internalizes environmental costs via eco-taxes, tradable permits, standards, and subsidies. Dense networks of civil society organizations, prepared to bring miscreants to task, diligently monitor detailed social-ecological performance reports and respond accordingly.

World Trade

Lest our regional focus leave the misapprehension that the world economy is no more than the sum of its parts, it is worth reiterating the essential role of global-scale institutions. World bodies marshal and organize the flow of “solidarity funds” to needy areas, implement transregional infrastructure projects, conduct space and oceanic exploration, and promote education and research for the common good. Moreover, world trade remains an important, if controversial feature of our interdependent economy.

How much trade is desirable? How should the system be designed? A few small anti-trade parties advocate extreme autarky, fearing a return to the discredited time when “free trade” was equated with efficiency and growth-oriented development. But with little likelihood that we will again mistake money for progress, most people believe rule-governed trade can make important contributions to Earthland’s core values.

First, interregional exchange can augment global solidarity by countering anachronistic nationalisms—when goods stop crossing borders, it has been said, bullets start to. Second, it can contribute to individual fulfillment by giving access to resources and products that are unavailable locally, thereby enriching the human experience. Third, it can foster win-win transactions that reduce environmental stress: food imports to water-parched areas, solar energy exports from deserts, and livestock exports from lands where sustainable grass-fed grazing is feasible.

For these reasons, the consensus is strong that, in principle, Earthlandic trade has a legitimate role. But in practice, the debate can be fierce on how to set the rules. The fundamental conundrum of world trade persists: how best to balance the pull toward open economic intercourse with the rights of localities to shield themselves from the disruptive power of unbridled markets. Trade negotiations bring all the tension between globalism and regionalism to the surface, leaving no easy resolution.

The tilt today is toward a circumscribed trade regime that seeks an equilibrium between cosmopolitan and communitarian sensibilities. Strictly enforced rules proscribe unfair regional barriers, especially actions that serve only to enhance the competitive position of home-based businesses. However, the rules do permit interdicting imports that would undercut legitimate local plans and aspirations. The Commonwealth’s dispute resolution system is busy, indeed, mediating the fuzzy boundary between perverse and virtuous protectionism.

As with much else, policy on trade varies across regions. Cosmopolitan Agorians tend to support it, welcoming the economic vitality and product diversity it brings. At the other extreme some Arcadian places have erected towering barriers to imports. Most regions fall in between free trade and protectionist poles, and all, of course, must adhere to globally adjudicated strictures and rules.

In aggregate, world trade, while still important, plays a lesser role than in globalization’s heyday at the turn of the century. The attention to the rights of regions to protect the integrity of their social models has bounded the scope for market exchange. Likewise, the rise in transport costs, as fuel prices came to fully incorporate environmental externalities, has added an economic advantage to the push for greater localization. Finally, the Commonwealth’s tax on traded goods and services, and cross-border monetary and financial transactions, restrains trade while generating revenue for global programs.

The Way We Are

So far, we have peered through a wide lens at our history, values, geography, and political economy. With that backdrop, let us focus on social dimensions of Earthland, and the people who live here.

People

Earthland’s population has now stabilized at just under eight billion people. Admittedly, this is a large number for a resource-hungry species on a small planet, but the point to underscore is that we are far fewer than the pre-transition projection of perhaps eleven billion people by the end of this century. By any measure, this has been a remarkable demographic shift made all the more impressive by the sharp increases in average life expectancy. The youth of today, who will benefit from further advance in biomedical science, can expect to be fighting fit at 100 years of age. And we present-day centenarians, born at the inception of the Great Transition, have every intention of participating in its next phase.

Of course, the story of population stabilization had a dark side—the decades of crisis and fear that cost lives and discouraged procreation—that must not be forgotten. Still, the primary and lasting impetus has been widespread social progress. Women elected to have fewer offspring in response to three intertwined factors: female empowerment, birth control, and poverty elimination. As girls and women gained equal access to education, civil rights, and careers, families became smaller everywhere, replicating a pattern already seen in affluent pre-transition countries. In addition, family planning services brought reproductive choice to the most isolated outposts and most recalcitrant cultural redoubts, largely eliminating unwanted pregnancies. Finally, the eradication of poverty, a central pillar of the new development paradigm, correlated with the demographic shift, as it always has.

Earthlanders reside in roughly equal numbers in Agoria, Ecodemia, and Arcadia. Current regional population distributions reflect the considerable interregional resettlement (about 10 percent of world population) as people were drawn to congenial places in the years after the Commonwealth was established. The flow has now largely abated, but a trickle of immigrants continue to exercise their right, as citizens of Earthland, to relocate. Thankfully, the old drivers of dislocation—desperate poverty, environmental disruption, and armed conflict—have largely vanished.

Agoria tends to be highly urbanized, Arcadians mostly cluster around small towns, and Ecodemia exhibits a mixed pattern. The “new metropolitan vision” that guides urban design has a central aim of creating a constellation of neighborhoods that integrate home, work, commerce, and leisure. This proximity of activities strengthens the cohesiveness of these towns-within-the city, while diminishing infrastructure and energy requirements. For many, these urban nodes ideally balance the propinquity of a human-scale community with the cultural intensity of a metropolis. But others are drawn to the lure of rural life, an especially powerful sentiment in Arcadia. Whatever the setting, citizens actively engage in common projects that foster cultural pride and a sense of place.

Family structures have evolved over the years to accommodate changing demographic realities, notably longer lives and fewer children. Naturally, Earthland’s socially liberal ethos welcomes a full spectrum of ways of living together, with the caveat that participation not be coerced. The traditional nuclear family endures, especially in Agoria, adjusting to highly fluid gender and caretaking roles as women gain equal status in all realms—or at least are moving in that direction in traditionally chauvinist cultures. Alternative arrangements proliferate as well, notably Ecodemia’s intentional communities and Arcadia’s mélange of communal experiments. Diversity in living choices, sexual orientation, and gender identity is part and parcel of the age of tolerance and pluralism. The approaches may vary, but a social priority—care for children, the elderly, and the needy—is a constant.

Time

A core objective of the “new paradigm” has been to fashion societies that enable people to lead rich and fulfilling lives. This endeavor has had economic and cultural prongs: respectively, providing citizens with the opportunity for this pursuit an cultivating their capacity to seize it. In its early decades, the Commonwealth focused on the economic preconditions of assuring secure, adequate living standards for all. This steadfast effort has radically reduced inequality and poverty and guaranteed a basic income, and increasingly provided people with more leisure time.

The cultural prong of nourishing human potentiality has been more challenging, and remains a work in progress, indeed, may forever so be. Still, never have so many pursued so passionately the intellectual, artistic, social, recreational, and spiritual dimensions of a well-lived life. Most Earthlanders, and nearly all youth, opt for lifestyles that combine basic material sufficiency with ample time for pursuit of qualitative dimensions of well-being. The few who are still enthralled by conspicuous consumption are generally considered rather unevolved aesthetically and spiritually.

The contemporary way of life depends on the abundance of a once scarce commodity: free time. Today’s citizens are highly “time affluent” relative to their forebears. Workweeks in the formal economy typically range from 12 to 18 hours (but far more for the pathologically acquisitive). The social labor budget—and therefore the necessary work-time per person—has steadily decreased. The arithmetic is straightforward. On the output side of the economic equation, technological progress has increased productivity (the quantity of goods and services produced in an hour of work). On the demand side, lifestyles of material moderation require fewer consumer products, and those products are built for longevity. Moreover, once prominent unproductive sectors like advertising and the military-industrial complex have shriveled, further reducing socially necessary labor time.

The payoff of this virtuous cycle is a two-sided coin: less required labor and more discretionary time. Critical to this lifestyle shift was the social shift that spread work time and, therefore, free time equitably. The foundations were laid by labor policies to ensure a decent job or basic income for all, welfare policies to meet the needs of the elderly and infirm, and economic justice policies to reduce disparities. Post-consumerist values spurred the search for a high quality of life, but economic equity was the prerequisite.

The passing of the era of long commutes also contributed to time affluence—and environmental and mental health. For local travel, we walk, bike, and make use of our dense network of public transportation nodes. For longer distances, rapid mag-lev networks link communities to hubs, and hubs to cities. The clogged roads and airport mayhem that tortured our grandparents have been abolished. People still drive, but sparingly, accessing vehicles through car-sharing arrangements for touring, emergencies, and special errands.

What do people do with their free time? Many craftspeople and service providers devote considerable effort in the labor-intensive “people’s economy.” But nearly everyone reserves ample space in their day for non-market endeavors. The pursuit of money is giving way to the cultivation of skills, relationships, and the life of the mind and spirit. The cynics of yesteryear, who feared the indolent masses would squander their free time, stand refuted. The humanists, who spoke of our untapped potential to cultivate the art of living, were the prescient ones. The limits to human aspiration and achievement, if they exist, are nowhere in sight.

Education

If it is true that education turns mirrors into windows, Earthland is becoming a house of glass. We have grasped well history’s lessons: an informed citizenry grounds real democracy; critical thinking opens closed minds; and knowledge and experience are the passports to a life lived fully. These convictions fuel peoples’ passion for learning, and society’s commitment to deliver a rich educational experience to all our young, and bountiful opportunity for lifelong learning.

The educational mission at all levels has expanded and shifted in the course of the transition. Here, we profile higher education, since universities have contributed mightily to the Great Transition by spearheading progressive change in the domains of education, research, and action. In the pre-transition decades, market forces had subordinated the traditional aims of humanistic education to the research and career training needs of the corporate state. Restive educators and students challenged the drift toward McUniversity, but deep reassessment and reform would await the cultural upheaval of the 2020s.

Prodded and inspired by the erupting Global Citizens Movement, universities played a vital role educating students, spreading public awareness, and generating knowledge for a world in transformation. Core curricula began to emphasize big systems, big ideas, and big history, thereby connecting cosmology and social history to the understanding of the contemporary condition and underscoring the problem of the future. Preparing students for a life of the mind and appreciation of the arts became the foundation for disciplinary focus and vocational preparation. Cutting-edge programs trained new generations of sustainability professionals equipped to manage complex systems, and scientists, humanists, and artists keen to enrich Earthlandic culture.

In parallel with this pedagogic shift came the equally significant epistemological shift that brought an emphasis on transdisciplinary study of the character and dynamics of social-ecological systems. Needless to say, all the old specialized fields continue to thrive, albeit with some, like economics and law, undergoing root-and-branch reconstruction. But the race goes, not to inhabitants of disciplinary islands, but to explorers of integrative knowledge frameworks. The excitement of Earthland’s intellectual adventure is reminiscent of the scientific revolution unleashed by the prior great transition to the Modern Era. The new revolution transcends the reductive and mechanistic models of old to place holism and emergence at the frontiers of contemporary theory.

Let us not fail to mention that the new university, beyond serving as a font of ideas and center of learning, became an important player in the transition unfolding outside its walls. Academic specialists brought a systemic perspective to advising governments and citizens groups on the transformation. Diverse public programs raised consciousness on the great challenges of global change. Most significantly, educational institutions were engines of change and loci of action. They still are, not least through educating tomorrow’s leaders, social entrepreneurs, and citizen-activists. The fully humanistic university has arrived, synergistically pursuing a triple mission—mass education, rigorous scholarship, and the common good—once thought to be contradictory.

Spirituality

The transition has left no aspect of culture untouched, and the forms of religion and spiritual practice are no exception. This is the way of the world: social transformations cause—and in turn are caused by—transformations in belief systems. Early Civilization brought forth the great world religions, which displaced paganism with new understandings of divinity and human purpose. Then, ascendant modernity transformed these powerful institutions and circumscribed their domain of authority as they adapted to the separation of church and state, the scientific worldview, libertarian social mores, and a secularizing culture.

When the Planetary Phase began roiling cultures in the decades around the turn of the century, decidedly illiberal streams pervaded most religions, resisting accommodation to globalizing modernity. Fundamentalism surged in reaction to the penetration of disruptive capitalism, which dissolved the consolations of tradition with the dubious promise of a purse of gold. In the vacuum of meaning that ensued, religious absolutism bubbled up, offering comfort for the lost and solace for the disappointed—and a banner of opposition for the zealous.

To this day, atavistic fundamentalist sects still practice their rigid customs and proffer literal interpretation of holy texts. These small groups may reject Earthland’s core principles of tolerance and pluralism, but nevertheless benefit from them. Their rights are strictly protected, subject only to the prohibition against the coercive imposition of beliefs on others. Late twenty-first-century fundamentalism, a curious throwback to a less enlightened era, reminds us of the timeless longing for unattainable certainty.

In the mainstream of the Great Transition, people were adjusting values and questioning assumptions. The search for new forms of the material and spiritual, and equipoise between them, led many beyond both hedonistic materialism and religious orthodoxy. The awakening spawned three central tendencies: secularization, experimentation, and reinvention.

Organized spiritual practice finds fewer adherents as interest wanes with each new generation. Suspicious of received authority and supernatural assumptions, more of us seek sources of meaning and transcendence in the wondrous marvels of art, life, and nature. Scholars debate the reasons for the diminishing draw of institutionalized religion (they have since the trend surfaced in Western Europe and elsewhere in the twentieth century). What is indisputable is that secularization has correlated with improved education and enhanced security—and, of course, with the expanding explanatory power of natural science.

As traditional forms contracted, new religious systems have proliferated, some created out of whole cloth and others as syncretic blends of ancient, modern, and New Age traditions. The breathtaking variety of this experimentation reflects the wide scope of spiritual ferment and cultural exploration stimulated by the transition. Each theology offers its disciples a unique metaphysics and, perhaps most importantly, a community of shared beliefs, rituals, and identity. Some groups worship sacred objects or pay obeisance to spiritual leaders, while those with a more pantheistic orientation seek direct experience of the divine, often through communion with nature. The new religions come and go, metamorphosing as they evolve and spread.

All the while, the old religions were transmogrifying and reinventing themselves as the strong bearers of planetary values that they have become. The Great Transition was in no small measure a struggle for the soul of the church, mosque, temple, and synagogue. By the early twenty-first century, prophetic voices in every religion were delving into traditional doctrine for roots of the modern agenda— tolerance, equity, ecology, fraternity—and finding anticipations. As the transition unfolded, the voices became choruses of interfaith ensembles spreading the word and marching in the streets.

Some historians belittle this “New Reformation” as a defensive adjustment to the cultural changes threatening to make reactionary theologies obsolete. It was more: the religious renewal was a vital prime mover of the new cultural consensus. Had these institutions not risen to the occasion and had particularism prevailed, one shudders to imagine how dismal the world might now be. In any event, the old religions endure, albeit at reduced size, attending to the well-being of their congregations and the wider world community.

Social Justice

The egalitarian impulse of the Great Transition has carried in its slipstream a firm commitment to social justice. By any measure, Earthland has become more equitable and tolerant than any country of the past, the fruit of the long campaign to mend deep fissures of class privilege, male domination, and bigotry of all shades. The triumph is real, but with the work of amelioration unfinished, it is too soon to declare the conquest of prejudice complete. Civil libertarians are right to warn of the dangers of apathy and retrogression.

Still, Earthland’s stunning erasure of grotesque disparities between rich and poor should not be minimized. Notably, income distributions have become far tighter than in the past: in a typical region, the highest earning 10 percent have incomes three to five times greater than the poorest 10 percent (national ratios a century ago were six to twenty). The wealth gap between haves and have-nots has also been closed by paring both the top and the bottom. Caps on total personal assets and limits on inheritance have made the super-rich an extinct species, while redistributive tax structures and a guaranteed minimum standard of living have nearly eradicated destitution.

Of course, economic justice is but one prong of social equity. More broadly, the ethical tenet that each person deserves equal moral concern has deep philosophic roots. The struggle for equal rights, regardless of gender, race, religion, ethnicity, and sexual orientation has a long and arduous history. Movements of the oppressed and aggrieved have been at the vanguard, and many quiet heroes have paid with their lives so that all could be free. Earthland’s egalitarianism and muted class distinctions opened a new front in this fight by dissolving entrenched structures of power, although elites long clung tenaciously to privilege. Perhaps most significantly, universal material security and access to education have reduced fear and ignorance, the primary ingredients that feed xenophobia and intolerance.

At the deepest level, the prevailing ethos of solidarity forms the bedrock for a culture of respect and care for every member of the human family. At last, the dream of full equality is close to fulfillment, and our vibrant rights movements deserve much of the credit. This towering landmark on the path of social evolution would not be on the horizon without their persistence and vigilance, and even now would remain vulnerable to stagnation or reversal. Prejudice and domination, the old nemeses of justice, are finally on the run.

Environment

We are the “future generations” spoken of in sustainability tracts of yore, the ones who would suffer the consequences of environmental negligence. Indeed, from its inception, Earthland has confronted the terrible legacy of a degraded biosphere and destabilized climate. The ecological emergency of the first decades of this century threatened to remold the planet into a bubbling cauldron of disruption, pain, and loss. Fortunately, this near calamity for civilization awakened the world’s people to the dire peril of drifting complacently in conventional development mode, and spawned the vibrant environmentalism central to the Great Transition movement.

Not content just to mourn the lost treasury of creatures and landscapes, activists mobilized to protect and restore what remained, and to set our damaged planet on the long path to recovery. The formation and consolidation of the Global Assembly for Integrated Action (GAIA) in the 2020s was a milestone in creating a powerful unified front for this effort. Its multipronged campaign—“the moral equivalent of war”—became the flagship collective initiative of the early Commonwealth, an endeavor that continues to this day.

A measure of GAIA’s success has been the significant contraction of the human ecological footprint, even as the world economy has grown. This sharp decoupling of economic scale and environmental impact was of critical importance to meeting and reconciling the goals of ecological sustainability and global equity. The key enabling factor was the change in culture and values that moderated the craving for tangible products. The shift in consumption patterns brought a corresponding shift in economic structure wherein sectors light on the environment—services, arts, health, knowledge—have become more prominent at the expense of industries highly dependent on natural resources.

In parallel, a host of technological innovations, such as nano-technology and bio-fabrication, brought leaner, longer-lasting products, while soaring carbon costs and rapid improvements in renewable energy and bio-applications turned out the lights on the fossil fuel age. The “waste stream” has been converted from a river of effluents to a primary input flow to industry. Ecological farming and mindful diets are the twin pillars of our sustainable agriculture system. Advanced techniques for removing atmospheric carbon from the atmosphere through enriched soils, bio-energy and sequestration, and carbon-fixing devices have been ramping up, as well.

These hard-hitting climate actions have set us on a trajectory to reach atmospheric carbon concentrations of 350ppm in the foreseeable future, a target once scoffed at by turn-of-the-century “realists.” Indeed, climate visionaries recently launched 280.org, a one-hundred-year campaign to return concentrations to pre-industrial levels. Other milestones are on the horizon, as well. Freshwater use is gradually coming into balance with renewable water resources nearly everywhere. As terrestrial ecosystems and habitats recover, species are being removed one-by-one from the endangered list. The oceans, the lifeblood of the biosphere, are healthier than they have been in decades—less acidic, less polluted, and home to more, and more varied, sea life.

The project of restoring the richness, resilience, and stability of the biosphere remains a vast collective cultural and political enterprise. People monitor sustainability indicators as closely as sports results or weather forecasts, and nearly everyone is actively engaged through community initiatives or GAIA’s global campaigns. At last, humanity understands the moral and biophysical imperative to care for the ecosphere, a hard-learned lesson that, future generations may be assured, shall not be forgotten. In our time, the wounded earth is healing; someday, the bitter scars from the past will fade away like yesterday’s nightmare.

In Praise of Generations Past

The state of the Commonwealth is strong and our grandchildren’s prospects are bright. But complacency would be folly. The immediate task is to heal the lingering injuries of the past—eradicating the last pockets of poverty, quelling old antagonisms that still flare across contested borders, and mending nature’s still-festering wounds. Strengthening educational programs and political processes is vital to solidifying Earthland’s ideals in minds and institutions. Social capital is the best inoculation against resurgence of the merchants of greed, demagogues of hate, and all who would summon the dark hobgoblins from the recesses of the human psyche.

Living in yesterday’s tomorrow, we proudly confirm what they could only imagine: Another world was possible!

The turning wheel of time no doubt will reveal twenty-second-century challenges now gestating in the contemporary social fabric. These days we are awash in speculative fiction about the shape of the future (or “analytic scenarios” in the terminology of ever-ambitious modelers). The avid space colonists of the Post-Mundial Movement dream of contact with an ever wider community of life. (Here the old guard of the GCM, noting the unfinished work on the home planet, uncharacteristically counsels caution.) Technological optimists envision the guided evolution of a new post-hominid species, hubristically so in the eyes of many humanists.

In fact, human history has not ended; in the fullest sense, it has just begun. We are entrusted with the priceless legacy of a hundred millennia of cultural evolution and emancipatory struggle that loosened the shackles of ignorance and privation. Now, we stand at the auspicious—and perhaps improbable—denouement of a century with an unpromising beginning. The timeless drama of the human condition continues in triumph and tragedy, but who among us would trade the theater of historical possibility that now opens before us?

How different is the ringing sense of expectation that surrounds us from the ominous soundtrack that rattled our grandparents’ youth, when the world careened toward calamity to a drumbeat of doom. But even then, those who listened could hear the chords of hope and feel the quickening rhythm of change. The Planetary Phase was relentlessly forging a single community of fate, but who would call the tune? Would the people of the world dance together toward a decent future?

Victor Hugo once noted that nothing is so powerful as an idea whose time has come. In the Planetary Phase, the idea of one world had finally arrived, but the reality did not fall from the sky. It took a tenacious few to sow the seeds as social conditions enriched the soil; the rest, as they say, is history. With profound gratitude, we honor the pivotal generations of the transition that rose to the promise of Earthland when the century was still young. Living in yesterday’s tomorrow, we proudly confirm what they could only imagine: Another world was possible!

Endnotes:

| 1. | ↑ | Although references to “Earthland” appeared years earlier, this was the first major document to employ the term. |

| 2. | ↑ | This treatise refers to sub-global demarcations as “regions” in adherence to the nomenclature recommended by the World Forum on Standards. Although traditionalists still speak of “nations,” the term conjures a bygone era of interstate wars, colonialism, and nativism that has been surpassed historically, and ought to be linguistically as well.

______________________________________ |

Paul Raskin is the founding president of the Tellus Institute. The overarching theme of Dr. Raskin’s work has been the development of visions and strategies for a transformation to more resilient and equitable forms of social development. He has conceived and built widely used models for integrated scenario planning for energy (LEAP), freshwater (WEAP), and sustainability (PoleStar). Dr. Raskin has published widely, and served as a lead author for the US National Academy of Science’s Board on Sustainability, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, the Earth Charter, and UNEP’s Global Environment Outlook. In 1995, he convened the Global Scenario Group to explore the requirements for a transition to a sustainable and just global civilization. The Group’s 2002 valedictory essay—Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead—became the point of departure for the Great Transition Initiative that Dr. Raskin launched in 2003 and continues to direct. His most recent publication is Journey to Earthland: The Great Transitionto Planetary Civilization. Dr. Raskin holds a PhD in Theoretical Physics from Columbia University.

Paul Raskin is the founding president of the Tellus Institute. The overarching theme of Dr. Raskin’s work has been the development of visions and strategies for a transformation to more resilient and equitable forms of social development. He has conceived and built widely used models for integrated scenario planning for energy (LEAP), freshwater (WEAP), and sustainability (PoleStar). Dr. Raskin has published widely, and served as a lead author for the US National Academy of Science’s Board on Sustainability, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, the Earth Charter, and UNEP’s Global Environment Outlook. In 1995, he convened the Global Scenario Group to explore the requirements for a transition to a sustainable and just global civilization. The Group’s 2002 valedictory essay—Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead—became the point of departure for the Great Transition Initiative that Dr. Raskin launched in 2003 and continues to direct. His most recent publication is Journey to Earthland: The Great Transitionto Planetary Civilization. Dr. Raskin holds a PhD in Theoretical Physics from Columbia University.

Earthland: Scenes from a Civilized Future is an excerpt from the recently published book Journey to Earthland: The Great Transition to Planetary Civilization, available in pdf at Great Transition Initiative website or in print at Amazon.com.

Go to Original – thenextsystem.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.