The Economy for the Common Good

PARADIGM CHANGES, 6 Mar 2017

Christian Felber and Gus Hagelberg | The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

27 Feb 2017 – This paper by Christian Felber and Gus Hagelberg is one of many proposals for a systemic alternative we have published or will be publishing here at the Next System Project. We have commissioned these papers in order to facilitate an informed and comprehensive discussion of “new systems,” and as part of this effort we have also created a comparative framework which provides a basis for evaluating system proposals according to a common set of criteria.

A Workable, Transformative Ethics-Based Alternative Introduction

- Introduction

The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is a comprehensive and coherent economic model and is being practiced in hundreds of businesses, universities, municipalities, and local chapters across Europe and South America. It represents an alternative to both capitalism and communism. It emerges out of a holistic worldview and is based on “sovereign democracy, stronger democracy than exists today.

The model has five underlying goals:

- Reuniting the economy with the fundamental values guiding society in general. The ECG encourages business decisions that promote human rights, justice, and sustainability.

- Transitioning to an economic system that defines serving the “common good” as its principal goal. The business community and all other economic actors should live up to the universal values set down in constitutions across the globe. These include dignity, social justice, sustainability, and democracy. These do not include profit maximization and market domination.

- Shifting to a business system that measures success according to the values outlined above. A business is successful and reaps the benefits of its success not when it makes more and more profits, but when it does its best to serve the public good.

- Setting the cornerstones of the legal framework for the economy democratically, in processes which result in concrete recommendations for reforming and reevaluating national constitutions and international treaties.

- Closing the gaps between feeling and thinking, technology and nature, economy and ethics, science and spirituality.

Rewarding “good” behavior, and making “poor” behavior more visible to the public and less profitable, will lead to a general paradigm shift at all levels of the economy. We will see more cooperation among business partners. We will see less uncontrolled, destructive growth, and companies will strive towards their optimal size. Business profits will increasingly be used to improve products, infrastructure, and working conditions and less for increasing dividends for investors, which widens the social divide.

The incessant drive for more and more profits and market share will slowly fade because this behavior runs in contradiction to the common good. ECG encourages private enterprise but only within the confines of a common good framework. Business activity that runs counter to the common good will no longer be hidden from the public eye and will worsen the company’s market performance. We will continue to have a free market economy, but not capitalism.

The tools and methods of the ECG can be applied at all levels of the economic and political realm. At the political level, various city and state governments have endorsed the principles of the ECG and are implementing its tools. The European Union and some European countries are considering applying ECG tools for new laws on issues such as non-financial reporting, public procurement, or investment guidelines.

At the business level, the ECG’s performance tool has been successfully implemented by over 400 businesses. Even some banks, universities, and NGO’s have adopted the ECG.

The model also entails a new approach to money, banking, and financial services. Money becomes a “public good” that serves the overarching goal of the common good.

The ECG is based on a proposal for sovereign democracy that provides citizens with “sovereign rights.” These include the exclusive right to change the constitution, the right to replace the government, and the right to stop a law which the legislature intends to pass, or to initiate a law by themselves. This brings the power back to the people, reduces political apathy, and will empower voters to get more involved in their communities and their places of employment.

The ECG cooperates with other social and new economy movements, not only to create synergies and join forces within the current system, but also to transform our political system towards a sovereign democracy.

The following ten principles help clarify the ideas and concepts underlying the ECG movement.

- The ECG strives towards an ethical market economy designed to increase the quality of life for all and not to increase the wealth of a few.

- The ECG helps promote the values of human dignity, human rights, and ecological responsibility into day-to-day business practice.

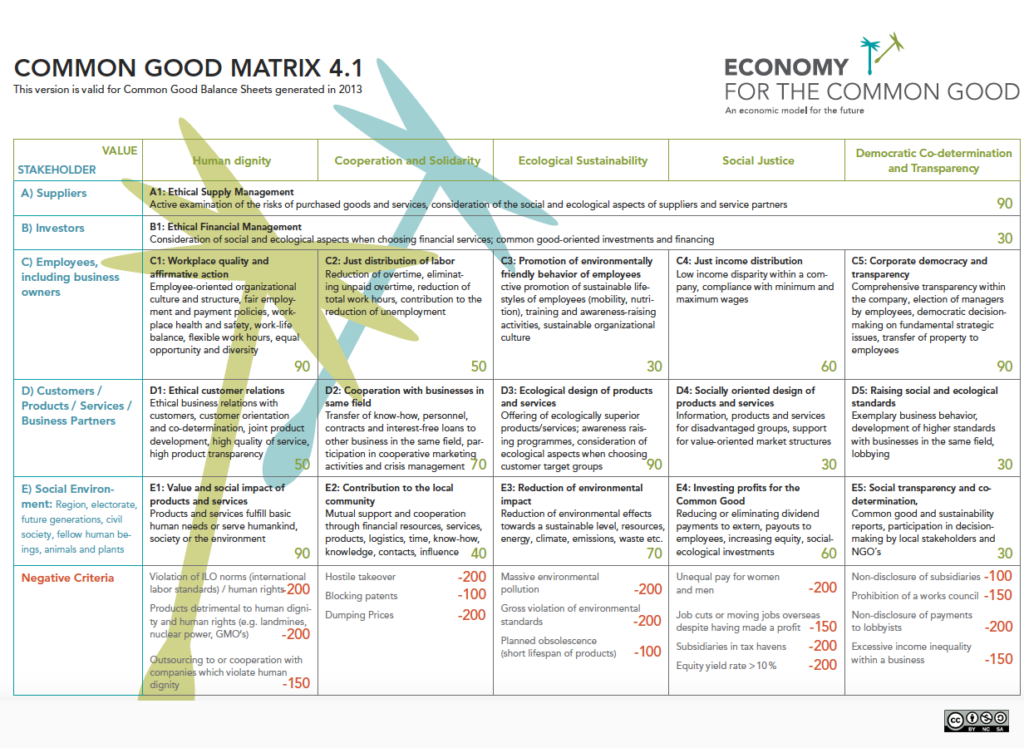

- The Common Good Matrix indicates to what extent these values are put into practice in a company. The Matrix is being continually improved upon in an open, democratic process.

- The Matrix provides the basis for companies to create a Common Good Balance Sheet. The Common Good Report describes how a company has implemented these universal values and looks at areas in need of improvement. The report and the balance sheet are externally audited and then published. As a result, a company’s contribution to the common good is made available to the public and all stakeholders.

- Common Good companies benefit in the marketplace through consumer choice, cooperation partners, and common-good-oriented lending institutions.

- To offset higher costs resulting from ethical, social, and ecological activities, Common Good companies should benefit from advantages in taxation, bank loans, and public grants and contracts.

- Business profits serve to strengthen and stabilize a company and to ensure the income of owners and employees over the long term. Profits should not, however, serve the interests of external investors. This allows entrepreneurs more flexibility to work for the common good and frees them from the pressure of maximizing the return on investment.

- Another result is that companies are no longer forced to expand and grow. This opens up a myriad of new opportunities to design business to improve the quality of life and help safeguard the natural world. Mutual appreciation, fairness, creativity, and cooperation can better thrive in such a working environment.

- Reducing income inequality is mandatory in order to assure everyone equal economic and political opportunities.

- The ECG movement invites you to take part in creating an economy based on these values. All our ideas about creating an ethical and sustainable economic order are developed in an open, democratic process, will be voted upon by the people, and will be enshrined in our constitutions.

- The Purpose of the Economy

What is the Economy Really About?

A central concern of the Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is to end the confusion between means and ends in our economic system. Money and capital should no longer be the end or the goal of economic activity, but rather the means to reach a higher goal, namely to improve the common good. This is by no means a new concept. The Greek philosopher Aristotle differentiated between “oikonomia,” the art of sustainably managing the house” (economy for the common good) and “chrematistike,” the art of making money (capitalism). In his concept of “oikonomia,” money only serves as a means. In “chrematistike,” as in capitalism, money and profit maximization become the bottom line. In an Economy for the Common Good, improving the well-being of everyone and of nature is the bottom line.

This concept was not lost in ancient Greece. Many western constitutions define the goal of the economy in this way. The constitution of Bavaria, Germany, for example, declares: “Economic activity in its entirety serves the common good.” In the Italian constitution it says, “Private economic enterprise is free. It may not be carried out against the common good.” In the preamble to the US Constitution it is stated that one goal is to “promote the general Welfare.”

Measuring the New Bottom Line

One innovative aspect of the ECG is redefining success according to a company’s contribution to the common good. The fundamental failure of the present system is that economic success is measured strictly according to monetary indicators, such as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for countries, or financial profit for businesses. Success is not measured in terms of the satisfaction of basic needs, quality of life, or protection of the environment. In a new economy designed to promote the common good, new methods will be available to measure success. At the national level, the Common Good Product will indicate a country’s success according to universal values. At the business level, the Common Good Balance Sheet will clearly show how much a company contributes to the common good.

The fundamental failure of the present system is that economic success is measured strictly according to monetary indicators, such as the Gross Domestic Product for countries, or financial profit for businesses.

Banking and finance will also need to reorient their priorities. Value-oriented indicators determine whether or not a person or company is creditworthy. At all three levels, monetary evaluations will continue to be necessary. GDP, financial balance sheets, and credit risk analyses will still be necessary. Common good indicators, however, will play a more important role than simple financial indicators.

At the national level, the definition of the Common Good Product should be determined by the sovereign citizens, perhaps in local assemblies. The idea is to identify the twenty most relevant aspects of quality of life and well-being and convert them to a measurable and comparable indicator. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) “Better Life Index,” the country of Bhutan‘s “Gross National Happiness,” and the Happy Planet Index are all examples of alternatives to GDP and can help define the most relevant quality of life indicators for a future Common Good Product.

If the Common Good Product of a country rises, its citizens can be sure that one or more of the following are true: unemployment and poverty rates have dropped, the incarceration rate is going down, income inequality has improved, and/or sufficient steps have been taken to address climate change. The GDP is useless in providing information about these important issues.

At the business level, the Common Good Balance Sheet (see next page) measures the extent to which a company abides by key constitutional values. These include human dignity, solidarity, justice, sustainability, and democracy. This new balance sheet measures some twenty ethical indicators; for example:

- Do products and services satisfy human needs?

- How humane are working conditions?

- How environmentally friendly are production processes?

- How ethical is the sales and purchasing policy?

- How are profits distributed?

- Do women receive equal pay for equal work?

- To what extent are employees involved in core, strategic decision making?

So far, over 400 businesses have conducted a Common Good Balance Sheet. Business owners, managers, and interested workers go through a catalogue of indicators and describe their activities accordingly. If desired, certified ECG business consultants support the company in addressing the issues, gathering the information, and determining the degree to which the company abides by the social and environmental performance indicators. Finally, independent auditors examine and discuss the results and a Common Good Report is published. All companies can reach a maximum of 1000 points. At present the average is around 300, which shows that companies across the board have room for improvement. If all companies scored 1000 points, we would have a near-perfect society: there would be no poverty or unemployment, a clean environment, gender justice, peace, and engaged and motivated workers. This utopia is of course very far away. We can, however, begin today to move in that direction.

Companies with high balance sheet scores could be rewarded with tax benefits, lower tariffs, better terms on loans, and priority in public procurement. As a result, ethical and environmentally friendly products and services would become cheaper than ethically questionable ones. Unlike today, where businesses are punished if they try to pay fair wages and protect the environment, responsible businesses in a common good economy would have an advantage in the marketplace. By reversing goals and means, the rules of the economy would be in line with human rights, justice, and democracy.

In Spain, Italy, Germany, and Austria, cities and state legislatures have already taken the first steps towards giving preferential treatment and grants to common good-oriented companies.

Use of Profits

Profits like money or capital, are economic tools. How a company uses its profits should be completely transparent and limited in scope. We as a society regulate business and individual activity in a multitude of ways. In order to drive a car on the highway we have to follow certain rules, like speed limits. A car manufacturer is required to ensure the safety of workers at its plants. The use of profits should not be an exception.

A company should be free to use its profits for the following activities:

- investments in the business;

- reserves for future losses;

- investments in capital reserves;

- dividend payouts to employees; and,

- loans to other businesses.

A company should be restricted in its use of financial surpluses for the following activities:

- investments in financial services; and,

- dividend payouts to proprietors and shareholders who do not work in the company.

Some practices could be outright forbidden, including:

- hostile takeovers and mergers; and,

- donations to political parties or PACs.

These proposals would help eliminate the constant drive towards profit-maximization and continual growth that is so prominent in our present system. The reorientation of profits would encourage businesses to shift their strategies towards increasing their contribution to society and the environment. Business would no longer be plagued with the ominous threat of failure if they did not increase shareholder value. The compulsion to grow and continuously gain more market share would also disappear. This would liberate businesses, allowing them to determine their optimal size and to focus on producing great products and services. Joel Bakan reminded us in his book, The Corporation, of the “public purpose” of the original corporations. Today, this focus has shifted to personal monetary benefits going chiefly to upper management and shareholders. ECG is, of course, not opposed to private companies and entrepreneurship. It simply proposes that they need to reorient towards serving the public good and abiding by values like human rights, human dignity, cooperation, sustainability, and democracy. The result is a free market economy, but capital accumulation is not the driving force.

From “Counterpetition” to Cooperation

One cornerstone of the capitalist market economy is the concept that competition is necessary for business. The Nobel Prize laureate for economics, Friedrich August von Hayek, wrote that competition is “in most circumstances the most efficient method known.” This concept has never, to our knowledge, been scientifically proven. People, including most economists, just assume it to be true. Research has shown, however, that cooperation, not competition, is much more effective in terms of motivating workers. Without motivated employees, one will not see improved innovation and efficiency.

Competition does, of course, motivate people and market capitalism has proven this, but it motivates them in very problematic ways. Competition can be seen as a win-lose situation. One person is only successful if another person is unsuccessful. Competition primarily motivates people through fear. Fear is a widespread phenomenon in market capitalism. Millions fear losing their job, their income, their social status, and their place in the community. Is this something we want to encourage?

There is another interesting aspect of motivation when it comes to competition. Competition elicits a form of delight in being better than someone else. This can, of course, have serious ramifications. The purpose of our actions and our work should not be to be better than others, but rather, to perform our tasks well, to enjoy our work, and to see that it is helpful and valuable. If you derive self-worth from being better than others, you are dependent upon others being worse. This actually constitutes pathological narcissism. Feeling better because others are worse off is sick.

If we look more closely at the term competition, we can see that its meaning has actually been largely distorted. The word competition comes from the Latin “cum” and “petere” which means “to search together.” This is, strangely enough, actually our understanding of the term cooperation. Today, however, competition means to search and act against each other, excluding others from the benefits of a new innovation or product. In Latin, we would call such a behavior “counterpetition” rather than competition. The ECG fosters true competition according to its original, literal meaning of working together.

Structural Cooperation

In the Economy for the Common Good, competition would not be eliminated. Negative behavior resulting from some types of competition, however, would reflect poorly in a company’s Common Good Balance Sheet. Aggressive behavior against competitors, such as hostile takeovers, price dumping, advertising via mass media, or enclosure of intellectual property, would reflect negatively on their ethical scorecard and harm their chances of succeeding in the market. The more cooperative their conduct was, and the more helpful they were with customers and competitors—for example, being transparent and sharing know-how, resources, and means of production—the better their common good score would be. The current win-lose paradigm would be replaced by a win-win paradigm. If enterprises were rewarded for cooperation, destructive competition would turn into peaceful coexistence at the very least. In some cases, proactive cooperation among businesses would result.

The pursuit of an optimal company size and thus the abandonment of the growth imperative would in itself encourage enterprises to engage in cooperation. A company that has reached its desired size has a much easier time sharing knowhow and even passing on contracts it cannot fulfill. From the theory of evolution, we have learned that a) more and more species are evolving and b) that certain species do not always endlessly grow until they die. The Harvard mathematician and biologist Martin Nowak writes, “cooperation is the chief architect of evolution.” 1It makes perfect sense to transfer this concept to the business environment.

Like all other ideas proposed, these reforms are meant to be changes in the legal framework of the economy. In order to make this happen, governments and parliaments should first be encouraged to implement the reform proposals directly through legislation. If they are not ready, or the political mandate is not yet strong enough, the reforms will have to be brought about by the “sovereign assemblies” described below, or via referenda. These are the foundation for a “true” democracy and will allow the people to change the economic order themselves.

- Property and Inequality

Property

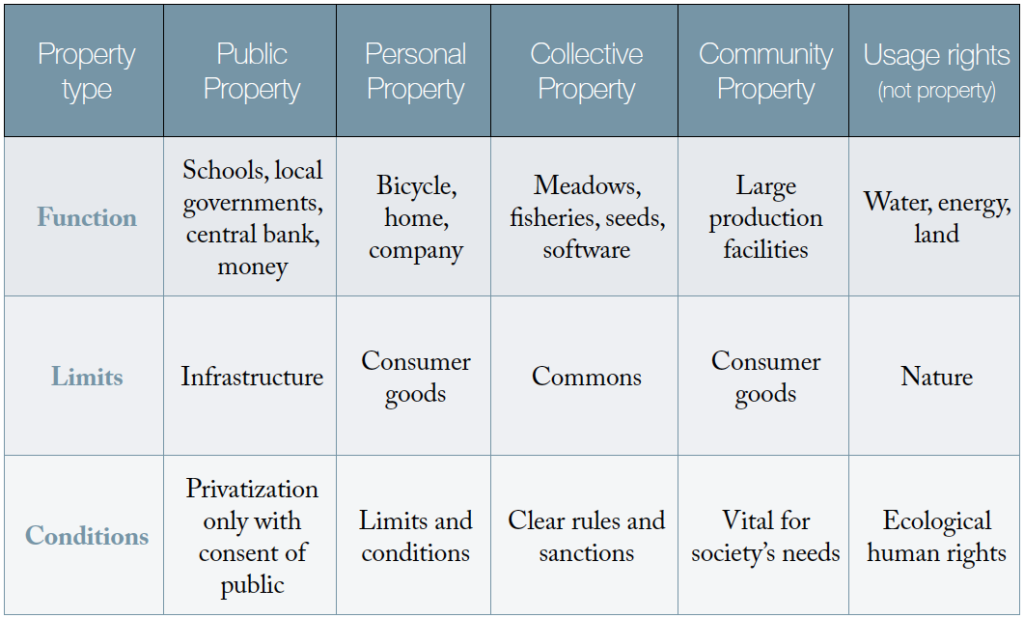

The starting point here is an historical dualism of two extremes. Socialist economic theories, on the one hand, place a very high value on public property. Capitalism, on the other hand, argues that private property is the most important form of property. The Economy for the Common Good envisions all types of property, putting none above the other, but placing limits and conditions on all of them. We argue, for instance, that it is good for a society when the government provides a broad range of basic infrastructure, ranging from water, energy, and transportation to health services, and education. If these services are free, at least for low-income individuals, they are an effective measure against poverty and exclusion. They strengthen social cohesion and the democratic community. On the other hand, there is no clear argument as to why government-run organizations would have to produce furniture, clothes, or food. Private companies can do this just as well, if not better, but under three conditions: the size of companies is regulated, common good balance sheets are compulsory, and inheritance is limited.

These limits and conditions would, for example, prevent excessive concentration of private property and ensure that it be used for the common good. A quote from Pope Paul VI can give us some orientation here: “the right of private property may never be exercised to the detriment of the common good.” 2

By reversing goals and means, the rules of the economy would be in line with human rights, justice, and democracy.

The commons are another form of property and constitute a cultural practice that enhances both ecological and social values. The commons should be protected by law.

As we will discuss below, a national constitution can provide guidelines as to the role private property, public goods, and the commons should play.

By social property, we mean companies that are controlled by their stakeholders— workers, customers, suppliers—but not investors that play none of these other roles. The Common Good Balance Sheet and its consequent incentives encourage all companies to become more like social businesses, or even like the commons. It’s not about coexistence of capitalist companies and the commons, but of ethical private companies, social companies, public services, and the commons.

There is one important exception to property rights and that involves nature. It was not humans who invented and created nature. We are creations of nature. In order to respect our origin and fertile earth, ECG proposes that there can be limited and conditional use of nature for commercial use, but no ownership of nature. That would prevent phenomena like land grabbing, real estate speculation, intellectual property rights on living organisms (such as genetically modified organisms), or massive deforestation.

This is an overview of the most important types of property, their function, limits, and conditions.

These reflections and proposals are rooted in the idea that all types of property are not ends in themselves, but basic rights that serve higher values such as human rights and social justice.

Income and Wealth Inequality

In the ECG we argue that it is of utmost importance to put limits on inequality. This can occur on many levels: income, property, inheritance, or the size of companies. According to a survey in the Financial Times and the Harris Poll, 78 percent of respondents in the US felt that inequality had increased too much. In the UK it was 79 percent, in China 80 percent, and in Germany 87 percent. 3

The international ECG movement uses an effective decision-making method called systemic consensus. It is a variant of consensus decision making and measures the amount of resistance to a proposal within a committee or larger group. Using this method, voters could, for example, determine the amount at which income should be limited.

Such “rehearsals” of democratic rights can be a good first step towards a “sovereign democracy” (discussed in more detail later in this essay). In systemic consensus, the first step is that all proposals presented to a given committee or group are voted on and the amount of opposition or aversion is measured. Each voter can express their opposition in three ways. By not raising any arms, a person expresses her lack of any aversion or resistance. By raising one arm, a person expresses that she has some opposition. By raising both arms a voter says she is totally opposed to the proposal and cannot accept its passage. Usually there are various proposals on the same issue. The proposal wins which has the least opposition.

ECG speakers have practiced this method with about 50,000 citizens from Sweden to Argentina to Chile. On the issue of limiting inequality and putting caps on income levels, participants in these “rehearsals” usually proposed either that maximum incomes within a company should be three, five, seven, ten, twelve, fifteen, twenty, fifty or 100 times higher than the lowest paid worker. Usually, a factor of ten was the most popular. The extremes of unlimited inequality as well as full equality frequently meet with strong resistance. Not surprisingly, a Swiss canton passed a law in 2013 limiting the highest salaries in public banks to ten times the amount of the lowest paid employee in the same bank. The minimum wage and maximum income are meant to be legal limits, whereas everything in between can be left to negotiation in free markets.

- Money and Finance Money as a Public Good

Similar to the business level, where profits become the means and the common good the end, priorities need to change in the realm of money and finances. Money should only be a means to reach a higher goal.

In order to accomplish this, money needs to become a public good. This means first and oremost that the rules of the monetary system are set by the sovereign citizens. In emocratically organized assemblies, the people define the cornerstones of a new monetary and financial system. Some core elements of this “sovereign monetary system” are:

- The central bank is a public institution whose organs are composed by all relevant stakeholders of society.

- The mandate and the objectives of the monetary policy are determined by the voters.

- The issuance of money becomes an exclusive task of the central bank. Private banks become pure intermediaries of “sovereign” money.

- The people decide where freshly created money goes. It can go to the government to alleviate public expenditures or directly to the citizens. In any case, the majority goes to the public.

- The goal of all certified banks must be to serve the interests of the general public. Just as public schools and hospitals, they are not allowed to, for example, freely distribute profits to their owners.

- Loans can only be granted for investments in the real economy, and for purposes that do not harm the public or the environment, not for buying on the financial market.

In order to accomplish this, loan requests will be assessed not only according to financial risks but, more importantly, according to their common-good creditworthiness.

“Return on Investment” Reexamined

Economists and finance experts regard an investment as successful if it generates a financial return. If the return on investment is double-digit, they regard it as particularly successful. This concept of success is flawed. The strictly monetary information provides us with absolutely no reliable information about the investment’s ecological or social impact. We cannot know how the investment affects working conditions, human rights, cultural diversity, or democratic principles. It is possible, in fact, that an investment yields extremely high returns but leads to job loss and environmental degradation. It could harm society in general and still be determined a success.

For this reason, financial institutions in an Economy for the Common Good will behave differently. The concept of return on investment will be reexamined. The validity of an investment will no longer be determined by monetary figures alone. The impact the loan plan has on a community, on the environment, and on working conditions will come to light. The return has to be beneficial to society and nature. A new bottom line comes into play.

Before granting a loan to a business or an individual, a bank will check the ethical creditworthiness. The customer will have to prove that the loan will not have a detrimental effect on the common good. Only if this ethical assessment is found to be positive, will the bank continue with the financial assessment. If the loan request passes both examinations, the bank grants the loan.

As a result of this new approach, borrowing costs will go down when the ethical value of an investment program goes up. Presently, borrowing costs go down when the financial credit risk goes down. Borrowers are rewarded when they prove they present little financial risk. In an ethics-based system, the borrowers are rewarded when they can prove that their project will benefit the public good and the environment.

If the investment is found to benefit the common good but the financial assessment is negative and the credit risk too high, the bank will probably refuse to grant the loan. In such cases, the loan plan could be handed over to cooperative banks or a crowd investment platform. By using these channels, loan-seekers with “good” but financially risky projects could still pursue their ideas even though the lenders may never see a single dime.

When higher financial returns are the main motive for investment decisions, we again see a twisted interpretation of means and ends. Financial gain is falsely viewed as a goal while the true goal, a safer and saner world, is lost. If we end the practice of judging creditworthiness strictly in financial terms, the logical goal and benefit for investors will become to increase the common good.

All in all, this new financial system will discourage investment decisions that endanger our fundamental values and encourage investments that have the most positive impact on the common good. They will not only be rewarded with a peaceful mind, but also with regional employment, meaningful jobs, strong and resilient local economies, reduced inequality and exclusion, and a large range of commons and companies that increase the common good.

Rewarding Ethical Investments

These concepts do not need to remain theoretical. These policy recommendations for the banking industry can already be implemented at the local or regional level. In the future we further envision these ideas being implemented at the national and international levels.

In order to continue operating in the market, banks can be given a choice. They can either become community-oriented, ethical, or cooperative banks, or they can be given access to the free market. Those banks that want to continue operating according to the old, capitalist model would be denied access to the (public) central bank, and would have reduced business with public authorities. If the sovereign citizens decided such, these banks could also be cut off from deposit insurance. They would probably have difficulty surviving on the market under such circumstances. One further result would be that “too big to fail” banks would most likely downsize or disappear because the risk of failure, a central tenant of free markets, would reappear.

- More Diverse Types of Business Entities and an Ethics-based Economy

As a consequence of the implementation of the principles and tools of the Economy for the Common Good, we foresee more diversity in the makeup of business entities, including:

- a greater number of smaller companies;

- more diverse forms of legal business entities; and,

- an increase in cooperatives, social businesses, benefit corporations, common-good companies and the strengthening of the commons.

The ECG represents a new type of market economy. This can be seen in three areas:

First, it is a fully ethical market economy. Economic success will no longer be judged in strictly financial terms. We will, therefore, see the emergence of a social, sustainable, cooperative, democratic, human market economy.

Second, it will be a truly liberal market economy in the sense that all market players will have equal rights, liberties, and opportunities.

Third, it will be a redesigned market economy in the sense that markets will continue to play an important role in satisfying basic needs, but not all of them. The new market economy will provide space for alternative cultural practices and alternative economic models designed to satisfy human needs. Examples are the care economy, gift economy, barter systems, local collaboration networks, urban gardening, peer-to-peer production, and the commons. These new informal structures will become more important and will receive more societal recognition.

In the long run, the average working time spent in waged jobs within formal markets could shrink dramatically without endangering a worker’s livelihood. If the average workweek for paid jobs is reduced to, for example, twenty hours, people will find time for other types of activities that are equally important to a good life. They will have more leisure time, more time to take care of family members, more time to work for their communities, and more time to participate in democratic decision making. This final point is particularly relevant because the “sovereign

democracy” model proposed by the ECG is a much more participatory and co-creative kind of democracy than most people know and imagine today. This requires more time and energy than is spent in our current democratic model.

- Democracy and Trade

Sovereign Democracy

Many argue that democracy in Western countries is failing. The English political scientist Colin Crouch describes our present form of democracy as “post democracy.” We argue that we actually live in “pre-democracy” because a true form of democracy, like direct democracy, has never actually existed.

In a true democracy, the sovereign people would be the highest authority—they would hold the ultimate power. This is the literal meaning of sovereign (Latin “superanus,” or standing above all). A true sovereign would stand above the legislature, the government, every international treaty, and every single law. This would mean that the sovereign citizens could directly modify the constitution and all laws. In order to modify democratic institutions and the rules of the economy, they would need the following “sovereign rights” to:

- draft a constitution (elect a constitutional convention and vote upon the results);

- change the constitution;

- elect a government;

- vote out a government;

- correct legislative decisions;

- directly put bills to vote (plebiscite);

- directly control and regulate essential utilities;

- issue money; and,

- define the framework for negotiations on international treaties and vote on the results of such negotiations.

The first sovereign right, the right of drafting a constitution, is the most important for the following reasons. First, the ultimate democratic document, the constitution, shall be written only by the highest authority, the people, and by no one else.

Second, if the constitution is written only by representatives of the citizens, they could award themselves additional powers and strip the people of their sovereign rights. When the people write the constitution, they determine the extent of power enjoyed by the legislative body and the government.

Third, the people could add certain fundamental cornerstones, and guidelines for the economy and democratic institutions directly into the constitution. As representatives of the people, the legislative body (congress or parliament) would retain the power to make laws. The people would become the constitutive power. Just as is the case today in democratic societies, laws would have to adhere to the constitutional framework. The difference is that the constitution would come directly from the people. Today, we see a great divide between public opinion and public policy. According to public opinion surveys across the globe, there are virtually no countries where the majority approves of the fact that banks can become too big to fail and are rescued with taxpayer’s money. Nor do people support the fact that capital is allowed to be freely transferred to tax havens, that patents are given on living organisms, or that genetically modified food is not labeled.

Once the aforementioned sovereign rights become reality, such divergences with public opinion will belong to the past. A constitution truly “by and for the people” would only need to contain certain key guidelines to ensure that the legislative branch does not drift too far from the will of the people. Decision-making in a Sovereign Democracy In order to practice the right to draft and amend the constitution, constitutional or “sovereign assemblies” can be created at the local level, and then at the regional level, and finally, at the national level. The assemblies prepare alternative proposals for each issue on the table. The sovereign citizens then make the final decision and choose the alternative of their preference. The proposal that meets the least resistance in the entire population is adopted. This innovative method is called “systemic consensus” and was developed by two mathematicians from the University of Graz, Austria. 4

The process of creating such democratic institutions has been drafted by the ECG movement. A more complete discussion about this topic can be found in Christian Felber’s book Change Everything. 5

In such sovereign assemblies, only fundamental questions should be discussed and decided upon. The legal implementation and the legal details are the legislature’s business. The people would decide on questions like:

- Do we want “okonomia” or “chrematistike”: economy for profits or economy for the common good?

- Should the central benchmark of economic policy be GDP, or a Common Good Product?

- Should money become a public good?

- Should companies be required to publish non-financial reports like the Common Good Balance Sheet if they want to receive an operating license?

- There are, fortunately, signs that people would opt for a Common Good Product over the GDP. In a representative survey among German citizens, ordered by the Federal Ministry of Environment, only 18 percent of the Germans would like the GDP to continue to serve as the most relevant benchmark for the economic and social policy. Sixty-seven percent of those surveyed preferred the replacement of the GDP with a more comprehensive indicator of life quality (e.g. Gross National Happiness).

Utilizing their sovereign rights, the people could vote on a compulsory common good balance sheet for all companies. Other authors, like Joel Bakan (The Corporation), David C. Korten (When Corporations Rule the World), George Monbiot (The Age of Consent), have argued that, at minimum, major corporations should only receive an operating license if their social, ecological, and ethical performance are deemed sufficient.

Sovereign citizens could also conduct a referendum to put a limitation on income inequality. In a multitude of “tests” conducted at speeches given across the world, Christian Felber has seen that the vast majority of his audiences say the income gap between the highest and lowest paid employees should be less than a factor of one to ten. Excessive pay is, unfortunately, the reality across the globe. InAustria, top executives are paid 1150 times as much as the lowest paid workers.In Germany it’s a factor of 1 to 6000 and in the US some top executives are paid

an incredible 350,000 times as much as the lowest paid workers. This is another clear example that sovereign citizens would make very different decisions from their representatives on such key issues.

International Trade

International trade is also a critical issue in the transition to an economy oriented towards the common good, and is closely related to democratic, sovereign rights. Local and national economies are strongly affected by globalization and trade. Present and past “free” trade agreements have been constructed on the premise that the more trade the better. Trade—just like money, profits, and growth—has been viewed as an end in and of itself. Trade is, however, not the goal. It is simply a tool that we can use to further our universal goals of improving human rights, justice, sustainability, and democracy.

The World Trade Organization (WTO), the Bilateral Investment Treaty, theTrans-Pacific Partnership (TTP), the Comprehensive Economic and TradeAgreement (CETA), and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership(TTIP) all blindly encourage more trade without judging its impact on the valuesof a democratic society.Here are some of the questions that should be at the forefront of all tradeagreements:

- Will the agreement comprehensively protect human and labor rights, and do the trade partners respect these rights?

- Does it enhance sustainable development and reduce the ecologicalfootprint?

- Does the agreement contribute to a more just distribution of wealth and to stronger social cohesion?

- Will it help close the gender gap and improve the inclusion of disadvantaged people?

If questions like these can be affirmed, then more trade should be welcomed. If the planned agreements endanger these values and the common good, then less trade would be better.

In order to determine whether the trade partners satisfy the requirements of a particular trade agreement, instruments such as various UN resolutions, human rights conventions, the Kyoto Protocol and the International Labor Organization (ILO) could be used. Those countries which have ratified and continue to respect these agreements would be able to trade more freely. In addition, tariffs could be progressively raised against countries that have violated the relevant international agreements.

In addition, countries with higher standards could protect their Ethical Common Market by asking companies who want access to the market to provide a Common Good Balance Sheet. According to their “ethical score,” they would get free access to the market, more costly access, or no access at all. The European Union has already begun to formulate policy for a “European Ethical Market.”6

The outcome in such an ethical trade zone would be similar to the situation at the business level when companies complete a Common Good Balance Sheet. “Good” behavior would be rewarded and “bad” behavior punished. Trade then turns into a positive and beneficial instrument for sustainable development and ethical business.

Such freedom of choice at the national level is not simply a utopian idea. The aforementioned country of Bhutan considered membership at the WTO in 2008. In the beginning, a clear majority of the population was in favor because more trade would have led to more business and economic growth. But after having seen the effect it would have had on the Gross National Happiness, the situation changed. In the end the government voted against joining the WTO. The citizens realized that this form of “free” trade would have meant increased unemployment, more inequality, the erosion of social cohesion, the loss of cultural diversity, and ecological instability.

Environment and Ecological Human Rights

The Common Good Balance Sheet is not meant to replace other policy instruments to achieve sustainable development. On the contrary, the challenge of deep sustainability is so big that a highly diverse policy mix is needed to obtain the ambitious goal of a sustainable human civilization. Unfortunately, most policy measures to date, from carbon taxes to subsidies for renewable energy and organic agriculture, have been relatively ineffectual. More ambitious proposals, like global resource management, have as of yet little chance of success. The climate crisis has reached epic proportions and requires epic solutions.

A radical, but also liberal measure would be the creation of ecological human rights. The idea is as follows: Mother Earth delivers to humanity a certain amount of natural resources and ecosystem services each year. This annual gift could be divided by the total number of human beings and allocated as a global per capita resource budget. In the same way as we manage to put a financial price on every product, we could add an “ecological price” to these natural resources. When a consumer uses a certain amount of a natural resource, they are charged a predetermined price, which is charged to their personal “ecological credit card.” This credit card is reloaded each year. When a person has “spent” their annual ecological credit, it is no longer possible for her to consume more natural resources. There will, of course, have to be mechanisms in place to prevent someone from starving or freezing to death. With this equal ecological right for all, everybody is totally free to consume resources and to shape her or his individual lifestyle as long as they don’t use up their credit. This is, in essence, a liberal approach.

One such method is the “doughnut model,” developed by Kate Raworth of Oxfam. It can help us better understand the concept of ecological human rights.

The model combines two limiting factors at the boundary of an imaginary biosphere. The first limitation, the outer circle, is Mother Earth’s yearly gift to mankind and is referred to as the “biological limit.” The inner circle defines the resources all human beings need to meet their basic needs. This is known as the “social limit.” The art of an ecologically efficient economy resides in maintaining mankind’s consumption of natural resources and its “ecological footprint” within these two limits. The goal is to protect (social) human rights and the (ecological) rights of Mother Earth.

An innovative combination of fundamental rights and market mechanisms could look like the following. The per capita consumption represented by the inner circle (the “social limit”) becomes an unconditional, non-negotiable, and inalienable human right. Whereas the amount between the two circles, the actual doughnut, becomes negotiable. Thanks to this measure, the poor could sell what they no longer need to the rich and the frugal could sell to the hedonists.

To better understand this idea, it could be helpful to expand the German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative to include the ecological dimension. Kant argued that you should “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” 6 Expanding this to the ecological dimension would mean that we humans should choose a lifestyle that can be chosen by all human beings without threatening the opportunities of others and those of future generations.

The ECG subscribes to a universal perspective on rights and criticizes anthropocentric approaches. This includes the rights of nature, which are the flip side of the coin of ecological human rights. Our proposal that private property should not include natural resources is a consequence of this ecological worldview.

Substantial scientific research concerning this issue has shown that reducing consumption of resources and material goods need not lead to a diminished quality of life. 7On the contrary, using less energy, oil, electricity, pesticides, and harmful additives can have the following benefits:

- Rivers, lakes, forests, and meadows could offer more recreational value.

- Homes would no longer require oil or gas because they would be so well insulated, made of natural materials and intelligently designed.

- Building materials would smell of natural wood and would be more pleasant to the eye and the touch.

- Food would be healthier and would provide us with more nutrients and energy.

- Our essential daily errands could be performed by foot or using convenient and comfortable public transportation.

- We could work in a stress-free environment, allowing for relaxation and enhancement of our self-esteem.

- Poverty could disappear once everyone in society had equal opportunities and rights.

If everyone could rest assured that their lifestyle did not rob those living in other corners of the globe and future generations of their sustenance, life would simply be better.

Education

One of the most important prerequisites for a flourishing Economy for the Common Good entails conveying new values, sensitizing people to their own human existence, rehearsing social and communicative competence, and setting an example when it comes to respect for nature. For this reason, ECG proposes the following subjects for all levels of education:

- Understanding Feelings

In this field of education, children would gain more experience perceiving feelings, taking them seriously, not being ashamed of them, talking about them, and regulating them consciously. Nonviolent communication has shown that myriads of conflicts in relationships remain unresolved because people are not able to talk about their feelings and needs. Society has failed to help children and young adults learn these skills.

We often learn instead to reproach those who do not fulfill our needs, and thus trigger a sense of injury. This diverts attention from our own needs and feelings and we end up hurting others in the process. An endless spiral of injury is the result, with the problem persisting and no prospect for a resolution of the conflict.

- Understanding Values

Here various attitudes towards values would be taught and discussed. This should include making children aware of subconsciously held biases and prejudices. Children would learn that they are capable of competing against each other and what the effects of this are. They would also learn, however, that they are capable of cooperation and could see what the effects of this are too. They would also learn the fundamental ethical principles of various philosophical ideas and religions.

- Understanding Communication

Here children start by learning how to listen, pay regard to others, take them seriously and discuss matters objectively without resorting to personal insult or judgments. This might seem obvious but we are light years away from an appreciative and nonviolent culture of public discourse. A democratic and nonviolent culture of discourse is characterized by the fact that we communicate with adversaries with respect and by presenting intelligent and cohesive arguments.

In the proposed educational program on understanding communication, children would also learn and become more aware about gender roles, and would learn techniques of avoiding the multitude of problems in this area. In this same way, intercultural communication skills could be taught. Moreover, children would learn that misunderstandings are normal and that creating understanding always takes a certain amount of effort.

- Understanding Democracy

Democracy is regarded with the utmost value in western societies. Yet the way this value can be lived and sustained—through personal intervention, encouragement of self-determination—is missing as a school subject. Democracy is presented as a reliable historical fact, not as a fragile, vulnerable accomplishment which can be lost at any time. Some argue, in fact, that democratic principles are already threatened because so many sectors of the population are disenfranchised, apathetic, and disillusioned.

Understanding democracy could include exploring the following elements:

- how to incorporate varied interests into one law or regulation;

- how decisions can be made without leaving a large minority unheard;

- that open, respectful encounters with others who have different views are a prerequisite for decisions which are supported by a large majority;

- that an alert commitment on the part of all is required so that special interests are kept in check; and,

- that democratic responsibility cannot be delegated, only the power to implement decisions.

The most important lesson to be learned is that democracy has just begun. We have only savored a thin slice of what is possible under democracy. The experience of “genuine democracy”—the motto of the Occupy Movement—has yet to be realized.

- Experiencing Nature and Understanding the Wildlife

An economy that relies on constant increases in money, income, assets, and material goods is sick in the sense that it has lost all sense of proportion. The difficulty many people have in relating to themselves, to other human beings, to their natural environment, and to the larger scheme of things is the core of this illness. Healing can consist of embracing these relationships, nurturing them, and bringing them into equilibrium. This is a reliable path to happiness. The authors have encountered countless people across the globe who report that having an intense, appreciative relationship with the environment, with living creatures, rivers, cliffs and celestial phenomena, has a healing effect. Spending several hours in intense communion with nature will most likely mean finishing the day with a sense of elation.

In this subject, children will not only learn how to identify plants, animals, bodies of water, and stones. They will also experience the healing effects nature has on their peace of mind. Wind and rain, clouds and water, stars, flowers, the mountains, tranquility—whoever has a deep connection to nature is likely to find little appeal in shopping centers, the stock market and, perhaps, the possession of an automobile.

In any case, experiencing a year of reduced material consumption can mean an increase in the intensity and quality of life even though, from the perspective of classic market economists, this means a betrayal of the economy, destruction of production sites, and recession.

- Crafts

The generation of “couch potatoes” spends an increasing amount of time in virtual spaces sitting at computers, talking on cell phones, watching television, or using any number of other electronic devices and media. This virtual world separates human beings from nature. One essential element of a holistic life lies in encounters with material, tools, shapes, colors, and smells in the natural world. We do not all have to become master craftspeople but we should all experience what it feels like to produce something manually and to give it to someone who can put it to good use. Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, advocated developing a comprehensive program for enabling pupils to come into contact with the “practice” of life, and for this reason Waldorf schools include internships n forestry, various trades, and social institutions in their curriculum. It is important to provide sufficient time for these activities so as to connect the inner self with the task at hand and unfold the entire creative potential which young people have. Creating useful things oneself creates meaning, and making gifts makes people happy. If some of these young people do become master craftspeople or artisans, then society surely will benefit.

- Sensitizing the Body

The Argentinian revolutionary leader Che Guevara reportedly said “solidarity is the tenderness of the people.” How can we expect governments and politicians to encounter each other with tenderness if we do not succeed in being tender to ourselves? Many of us eat poorly, get too little exercise, show little physical affection, or rarely give or receive a massage. Massages are, in fact, one of the easiest and fastest ways of becoming happy. If we compare the time we spend shopping, watching television, and earning money with the time we spend giving or getting a massage, we see how much physical touch and tenderness we lack. The human body is an endlessly sensitive organism and we all possess the disposition which allows us to sense things so finely that each step and each contact with an object can lead to a deep sensual experience or massage of the inner self. With sensitivity training, the intensity and quality of life would increase to such a degree that there would hardly be any time left for non-sensual experiences. The weaker the sensual element, the weaker the physical self-perception, and the more compensation needed in the form of consumption and drugs.

For this reason, children should be encouraged to develop a fine, attentive, and appreciative relationship to their own body, their creativity, and authenticity. This can begin with games, dance, and group acrobatics and later, after puberty, be expanded to include elements of bodywork, massage, energy work, and yoga.

True Universities and Economics

The field of economics has been separated from other disciplines and from other parts of human and planetary life such as feelings, values, democracy, and nature. This is just one symptom of a progressive fragmentation of the scientific world. The word “university” comes from “uni” and “verse” and means literally “turned into one.” Everything is a coherent whole.

Accordingly, the fragmentation of science is the exact opposite of what the institution “university” promises in its name. A true, holistic university could be designed in two parts. First, all students get to know the whole picture in an overview of all disciplines and their interconnections and analogies. Second, they can specialize in what their interest is drawn to.

Such a holistic university would offer three advantages compared to today’s institutions of higher education. First, everyone who has attended university would have a common ground and base of conversation with everyone else. Second, the danger that technical studies would be separated from nature, or economics from ethics, would be reduced. Third, although it is just an assumption, such university studies would, in general, be much more interesting and attractive.

- Real-World Examples, Experiments, and Comparable Models

The ECG Movement

The international movement “Economy for the Common Good” began in October 2010 on the initiative of a dozen companies in Austria. Since then, some 2,200 businesses from fifty nations have joined the movement, 400 of them have already implemented the Common Good Balance Sheet. There are three banks among the pioneers and a multitude of public institutions such as the University of Applied Sciences of Burgenland, Austria, which recently elected a “Common Good Officer.” The Universities of Flensburg and Kiel in Germany have started a three-year research project to examine how well the balance sheet can be implemented in large corporations. Three major corporations on the German stock exchange (DAX) are taking part in the study. The University of Valencia, Spain will establish a chair dedicated to the Economy for the Common Good, and the University of Barcelona, Spain has applied for a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Chair dedicated to the ECG.Other schools and universities have integrated the model in their curriculum or have completed the balance sheet.

More and more municipalities are also joining the movement in Spain, Italy, and Germany. Some are becoming common-good cities, while others are adopting policies to encourage companies to complete a Common Good Balance Sheet. The northern Italian state of South Tyrol has voted to give enterprises with high common-good scores priority in public procurement. The German state of Baden-Württemberg, with a population of over ten million, has endorsed the ECG model.

The five-years-young ECG movement celebrated a major success at the European Union in September 2015. The European Economic and Social Committee, a 350-member advisory body to the Commission and the Parliament, approved an “opinion” on the Economy for the Common Good. It was approved in its plenary session with an overwhelming majority of 86 percent. The committee’s declaration argues that “the Economy for the Common Good (ECG) model is conceived to be included both in the European and the domestic legal framework.” 8

The ECG movement consists of some 200 local chapters in twenty countries. Dozens of permanent working groups called “hubs” work as editors on the content of the Common Good Balance Sheet, as ECG-certified business consultants, auditors, speakers, ambassadors, and much more. Delegates from local chapters and hubs meet once a year in the delegates’ assembly and vote on all strategic decisions using consensus decision making. At present, twenty legal associations have been founded, and this year the international ECG federation will be established in order to coordinate the global activities.

The 400 companies that have implemented the balance sheet started the process of creating more transparent, worker-friendly, sustainable, and social businesses. The steps can be very small. The Italian hotel “La Perla,” for example, introduced one meat-free day per week.9 Some ECG-certified companies have switched to renewable energy sources and recycling paper. The Sparda Bank from Munich, Germany decided to get rid of commissions on loan contracts.10

Changes can also be very big. A company based in Salzburg, Austria was run in a classic manner by the single owner. When implementing the balance sheet for the first time, the employees started to articulate their opinions and critiques. This led to changes and improvements at various levels of the company. Today, the majority of the employees are co-owners of the company.

A medium-sized furniture manufacturer reoriented his marketing strategy. Previously, the owner struggled to sell as much as possible, whether or not his customers needed the products. After being introduced to the ECG, he changed his policy and began selling his customers only what they really needed. This change—which we could consider a shift from the growth and maximization paradigm to a “degrowth” or steady-state paradigm—came after the company closely examined the indicator relating to ethical sales in the Common Good Balance Sheet. A list of companies which have gone through the certification process can be found here: http://balance.ecogood.org/ecg-reports/ecg-audited-organisations-feb2016.xlsx/view

Common good-oriented companies have also begun to cooperate more with competitors and are shifting more towards ethical banks. One emblematic project is a “common good bank” in Austria that was launched simultaneously with the ECG movement. The organization directing the bank is a cooperative, and has built on the examples of ethical banks in Germany, Holland, Switzerland, and Italy. It has gone one step further and added policies that ensure there will be no distribution of financial profit to the owners, zero-interest loans, and compulsory common good examinations for all loan plans.

The cooperative has collected over three million euros from over 4,000 members. Within the next year, the “Bank for the Common Good” will be able to open its doors to business. The cooperative will not only provide financial services, but will also start an academy on money alternatives and a think tank for the common good.

Today, ethical banks and fair trade initiatives are only a drop in the global capitalist bucket. By implementing the methods described above—such as an ethical creditworthiness check and The Common Good Balance Sheet—they can become mainstream.

Another real-world example is the tiny state of Bhutan. There the nation’s progress is not measured using GDP, but via the Gross National Happiness (GNH) index. Every two years, several thousands of households are asked about all aspects of quality of life– from subjective well-being, health, and education to the quality of social relations, trust, and safety. GNH is not just an indicator, but a tool for strategic political decisions. One example, as mentioned above, is the country’s decision not to enter the WTO.

In two other small countries, Switzerland and Iceland, fundamental reforms of the monetary system are being discussed. In Switzerland, a national referendum called the “sovereign money initiative” will be voted on in 2018.11 In Iceland the government itself is debating a “positive money reform.” Both reforms would hand over the exclusive right to print money, including so-called “book” or “electronic” money, to the central bank.

Comparable Models, Collaboration

The ECG movement is collaborating with many movements and initiatives. The plethora of practical, lively, and powerful movements easily proves Margaret Thatcher wrong when she declared, “There is no alternative” (TINA) [to capitalism]. We prefer “TAPAS” or “There are plenty of alternatives.” These alternatives include: the commons movement, the solidarity economy, the Degrowth Network, Post Growth Alliance, Transition Town, Circular Economy, ethical banking, Fair Trade, B Corps, and many others. On the one hand, ECG is networking,

reinforcing, and spreading the word for the others. On the other hand, it provides a framework in which parts of various alternative models can be integrated, implemented, and creatively combined. For instance, ECG proposes the reduction of the average workweek on markets to about 20 hours per week. This would free time to engage in commons, collaborative, and gift economy practices. Or, if cooperatives implemented a Common Good Balance Sheet, they would finally enjoy competitive advantages relative to transnational corporations and shareholder-based companies. A third example is the idea of “ecological human rights,” which could become an effective tool for post-growth in the material and biological dimensions of the economy. At the same time, concrete proposals from other initiatives can be integrated into a democratic, common good-oriented, sustainable, cooperative, just, and humane economic system of tomorrow.

Creating an Economy for the Common Good

While the ECG movement has made impressive progress since its inception just five years ago, there is clearly a long way to go before this economic model is realized. Voluntary measures will not be sufficient. Policy changes, mandates, and new legislation will be required. The ECG is fully committed to the principles of democracy and realizes that “true” democracy is a prerequisite to radical, systemic change. The concept of sovereign democracy and democratic constitutions is designed to ensure full participation in the creation of an economy based on

the common good.

The following steps will be necessary in order to affect deep-rooted, systemic change and to create an Economy for the Common Good:

- More and more businesses voluntarily create common good balance sheets based on their intrinsic motivation.

- Public pressure increasingly encourages legislators at the local, state, national, and international levels to mandate ethics-based balance sheets.

- Municipalities and regional governments endorse the ECG and become Common Good cities and regions. Cities and regions then require common good balance sheets from companies who receive government contracts and initiate or support democratic assemblies of citizens.

- Local democratic assemblies are synthesized at the national and supranational level. As a result of this process, the people can amend the constitution and thereby create a different legal

framework for the economy, which is in line with their valu10es.

Endnotes:

| 1. | ↑ | Martin Nowak, Supercooperators: Beyond the Survival of the Fittest: Why Cooperation, Not Competition, is the Key to Life (Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd., 2012). |

| 2. | ↑ | “Populorum Progressio, Encyclical of Pope Paul VI on the Development of Peoples,” The Vatican, March 26, 1967, Paragraph 23, http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_26031967_populorum.html. |

| 3. | ↑ | John Thornhill, “Income Inequality Seen as the Great Divide,” Financial Times, May 19, 2008. |

| 4. | ↑ | “Systemisches Konsensieren,” www.sk-prinzip.eu. |

| 5. | ↑ | Christian Felber, Change Everything: Creating an Economy for the Common Good (London: Zed Books Ltd., 2015). |

| 6. | ↑ | Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, Ellington, James W., trans. (Indianapolis, IN: Hacket, 1993 [1785]), 30.). |

| 7. | ↑ | Richard Layard, Happiness: Lessons from a New Science (London: Penguin, 2005); Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level. Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (London: Penguin, 2010). |

| 8. | ↑ | “Economy for the Common Good,” 2015. |

| 9. | ↑ | Hotel, Laperla, http://www.hotel-laperla.it/en/pills/common-welfare-economy/14-699.html. |

| 10. | ↑ | Sparda-Bank, https://www.sparda-m.de/gemeinwohl-oekonomie.php. |

| 11. | ↑ | “Campaign for Monetary Reform – News from Switzerland,” Vollgeldinitiative Schweiz: English, http://www.vollgeld-initiative.ch/english. |

________________________________________________

Christian Felber, born in 1972, studied Spanish, psychology, sociology and political science in Madrid and Wien. He wrote and coauthored fifteen books and teaches at Vienna University of Economics and Business. He is an international speaker, contemporary dancer, and founder of the Economy for the Common Good movement. In September 2016, he visited the United States to talk about his book, Change Everything.

Gus Hagelberg, born in 1966, received his BS in political science from the California State University, Chico and his MS in political science from the University of Tübingen, Germany. He is presently Coordinator for International Expansion of the ECG.

Go to Original – thenextsystem.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.