Cultivating Community Economies

PARADIGM CHANGES, 3 Apr 2017

27 Feb 2017 – This paper is one of many proposals for a systemic alternative we have published or will be publishing here at the Next System Project. We have commissioned these papers in order to facilitate an informed and comprehensive discussion of “new systems,” and as part of this effort we have also created a comparative framework which provides a basis for evaluating system proposals according to a common set of criteria.

Tools for Building a Liveable World

The Community Economies Collective (CEC) seeks to bring about more sustainable and equitable forms of development by acting on new ways of thinking about economies and politics. Building on J.K. Gibson-Graham’s feminist critique of political economy, the CEC challenges two problematic aspects of how “the economy” is understood: seeing it as inevitably capitalist, and separating the economy from ecology. We understand the economy as comprised of diverse practices and as intimately intertwined with planetary ecosystem processes. In a complexly determined world there are multiple ways of enacting change; we are energized by possibilities that are afforded by this framing of economy.1

To try to mobilize social transformation we have worked on 1) developing a new language of the diverse economy, 2) activating ethical economic subjects, and 3) imagining and enacting collective actions that diversify the economy. For us, these actions comprise a “post-capitalist politics.” We do not place “the economy” at the center of social change, as for us there is no privileged “center,” nor one determining dynamic of transformation. We believe in starting where we are, building other worlds with what we have at hand. Our particular focus is on identifying, gathering, and amplifying ethical economic practices that already exist—and that are prescient of “the world we want to live in.”

Key Commitments

- The Community Economies Collective adopts an anti-essentialist thinking approach. Instead of reducing the world to a few key determinants, we understand the world as shaped by multiple and interacting processes, only some of which we can apprehend. This approach helps us recognize the power and efficacy of things that might seem small and insignificant. It also means that we are open to the unexpected and the unknown.

- The Community Economies Collective affirms that lives unfold in a “pluriverse” rather than a “universe.” This means there are a range of solutions and strategies for change, and multiple pathways towards more sustainable and equitable worlds.

- With others, the Community Economies Collective is involved in on-going processes of learning and “becoming ethical subjects” through negotiation with human and “earth others” (species, ecologies, landscapes and seascapes). We aim for ongoing, courageous, and honest ethical relationships and transformation rather than a utopia. We recognize that there is probably no final or most desirable state of ethical being.

These commitments have evolved from critical engagements with a range of political and intellectual traditions. The CEC’s work is most readily identified with feminism, having developed out of a feminist critique of the essentialism and capitalocentrism at work in both mainstream and Marxian economic discourses. Feminist theory liberated the category “woman” from its positioning as subordinate to “man,” the stand-in for the “universal” human subject. In a similar vein we have worked to liberate the plethora of non-capitalist economic activities from a subordinated positioning with respect to “capitalism,” the stand-in “model” of economy. Our feminism is concerned to address questions of gender inclusiveness and equality, but it extends far beyond this to influence all aspects of our everyday practice. We see feminism as foregrounding relationality and ethical care of the other.

We have used Marx’s analysis of “class as a process” (of producing, appropriating, and distributing surplus) to unpack the diversity of economies that exist in any historical or geographic context.

Anti-essentialist Marxian political economy has been another formative influence on the work of the CEC. We have used Marx’s analysis of “class as a process” (of producing, appropriating, and distributing surplus) to unpack the diversity of economies that exist in any historical or geographic context. By recognizing the contemporary coexistence, rather than historical sequencing, of different class processes (independent, feudal, capitalist, communist) the dominance of “capitalism” is deconstructed, thus opening up radical possibilities for heterogeneous economies. We employ both anti-essentialist Marxism and post-structuralist feminism as strategies to “queer” the economy and indeed society—that is, to resist the alignment of aspects of identity (whether of class, gender, sexuality, or race) into seemingly intractable “structures.” We see that the invocation of such “structures” serves to deny the possibility that other ways of being and indeed other worlds are possible.2

Understandings of Transformation

Our engagements with these traditions have led to the following views on transformation:

- Radical transformation is possible. The revolutionary transformation of lives that feminism has wrought in living memory is one source of inspiration for our project—prompting us to look for the range of contributors to change (organized, disorganized, social, technical, contextual).

- How we construct stories or narratives of transformation is important. These narratives have what some social theorists call “performative effects.” In other words, our narratives help to bring into being the worlds they describe. We are aware that the stories we tell can sometimes make the things we’re trying to change seem more powerful, and can therefore close off possibilities for change and dampen transformative inspiration. Stories of capitalism or neoliberalism can have this effect. It is therefore crucial that we cultivate representations of the world that inspire, mobilize, and support change efforts even while recognizing very real challenges.

About the Community Economies Collective (CEC)

The Community Economies Collective (CEC) was formed in the 1990s by Katherine Gibson and the late Julie Graham (aka J.K. Gibson-Graham) and a group of scholars committed to theorizing, representing, and enacting new visions of economy. The thirty-eight members of the CEC are mostly based in academic contexts in Australia, Europe, New Zealand, and the US. Their action-research engagements are, however, more geographically spread across the globe. The CEC convenes a Community Economies Research Network (CERN) of some 140 (and growing) members in Africa, Australia, Europe, Latin America, and North America. CERN members include a group of ten to fifteen artist-activists engaged in exhibitions that take up the issue of alternative economies and worlds. Regional clusters of the CERN meet to discuss research, organize conference panels, and develop new collaborations. The outputs of the CEC include scholarly articles and books, popular books, videos, and websites. Members of the CEC have recently launched the Diverse Economies and Liveable Worlds book series with the University of Minnesota Press.

Community Economies

The term “community economy” is often used to refer to localized business activity. This is not the way that we use it. Our collective project involves challenging conventional definitions of both “community” and “economy,” generating a different approach to how we understand and engage with ways of living and working.

“Community”

Community, for us, refers to the active, ongoing negotiation of interdependence with all life forms, human and nonhuman. The outcome of this negotiation cannot be specified in advance, or in any abstract, generalized theory. Community is not a fixed identity nor a bounded locality, but is a never-ending process of being together, of struggling over the boundaries and substance of togetherness, and of coproducing this togetherness in complex relations of power. We seek to emphasize here a focus on process rather than on product, on struggle and deliber-ation rather than on an image of a predefined collective identity or geographical locality. The key question for us, when engaging in questions of “community,” is whether the dynamics of being together are obscured and made difficult to challenge and change, or whether they are made explicit and opened for collective negotiation and transformation. In other words, is the ongoing making of community a truly democratic process?

“Economy”

In conventional usage, economy often refers to a system of formal commodity production and monetary exchange. Our use of the term is much broader. The “eco” in economy comes from the Greek root oikos, meaning “home” or “habitat”—in other words, that which sustains life. The “nomy” comes from nomos, meaning management. We view economy as referring to all of the practices that allow us to survive and care for each other and the earth. Economy, in this understanding, is not separate from ecology, but refers to the ongoing management—and therefore negotiation—of human and nonhuman ecological relations of particular logic or rationality (individual utility maximization, for example); rather, they are diverse, complex, and contextually situated, animated by multiple motivations and relational dynamics. We prefer to talk, then, in terms of “economic practices” or “economies” rather than about “the economy” or “the economic system.”

“Community + Economy”

Community economy names the ongoing process of negotiating our interdependence. It is the explicit, democratic co-creation of the diverse ways in which we collectively make our livings, receive our livings from others, and provide for others in turn.

To help make these complex negotiations more clear, CEC identifies a cluster of ethical concerns or “coordinates” around which community economies are being (and might be) built. They are:

- SURVIVAL. What do we really need to survive well? How do we balance our own survival needs and well-being with the well-being of others and the planet?

- SURPLUS. What’s left after our survival needs have been met? How do we distribute this surplus to enrich social and environmental health?

- TRANSACTIONS. What are the range of ways we secure the things we cannot produce ourselves? How do we conduct ethical encounters with human and non-human others in these transactions?

- CONSUMPTION. What do we really need to consume? How do we consume sustainably and justly?

- COMMONS. What do we share with human and non-human others? How do we maintain, replenish, and grow this natural and cultural commons?

- INVESTMENT. What do we do with stored wealth? How do we invest this wealth so that future generations may live well?

The following examples (in alphabetical order) provide just a snapshot of the ways that already existing initiatives are negotiating these ethical concerns.

Alter Trade Japan

Alter Trade Japan (ATJ) is a global network that uses transactions as a vehicle to help people survive well and protect their natural and cultural commons. ATJ was formed in the late 1980s as a long-term trade initiative that would take over from the short-term emergency relief work of the Japan Committee for Negros Campaign. This committee was providing support for starving sugarcane farmers on Negros Island who had lost their livelihood when the international sugar market collapsed. From these beginnings, ATJ has expanded to source a range of fairly produced food-stuffs for Japanese consumer cooperatives. Products include natural sea salt from the once threatened saltpans of France, olive oil from Palestine, “eco-shrimps” from extensive fish farms in Indonesia, and Balangon bananas from the Philippines.

The Chantier de l’économie sociale, Québec

The Chantier is a nonprofit entity that serves existing and new enterprises in the social economy in Québec, particularly through investment strategies. It has recently developed two financial tools for social economy enterprises. These enterprises channel surplus into shared social outcomes. The Réseau d’investissement social du Québec (Social Investment Network of Quebec) helps to finance social economy enterprises in the start-up, consolidation, expansion, or restructuring phase. The Chantier de l’économie sociale Trust provides loans exclusively for social economy enterprises (especially nonprofit organizations and cooperatives with under 200 employees). These loans have a fifteen-year capital repayment moratorium—hence the designation of “quasi-patient capital.” The Chantier estimates that there are over 7,000 collective enterprises (cooperatives and nonprofit busi-nesses) in Québec, providing over 150,000 jobs and contributing over 8 percent of the province’s GDP. Critical to the operations of the Chantier is the board which functions as a network of networks, with representatives from: associa-tions of social economy enterprises, the main labor federations and members of these federations, the cooperative movement, the women’s movement, the social movement (including environmental and cultural movements), and Québec-wide associations of First Nations and Inuit peoples and their member groups.

Hepburn Wind

Hepburn Community Wind Park Co-operative (Hepburn Wind) is an example of community-driven investment being used to support a shift towards more sustainable consumption practices and to distribute surplus for social benefit. Hepburn Wind is based in rural Victoria, Australia and it owns two turbines with a combined capacity of 4.1 megawatts, which can produce enough electricity to power 2,300 homes. This is an important contribution to changing energy consumption practices in a country that has one of the world’s highest levels of per capita consumption of coal. There are 2,000 cooperative members and they contributed AUD$9.8 million to the construction of the wind farm. Over half of these members are local residents who were encouraged to join; minimum shares for local members were at $100 (as opposed to the minimum of $1,000 for non-local members). The Victorian state government also provided grants totalling $1.7 million and a community-run bank provided a $3.1 million loan. The initiative generates surplus which is returned to members as dividends. However, there is a priority placed on community projects; each year $15,000 per turbine is placed in a Community Fund for projects that will strengthen the environmental, recreational, cultural, and educational well-being of the local area (and this funding is allocated before any dividends are paid). With indexing, the Community Fund will total more than $1 million over the next twenty-five years.

Kerala

For over fifty years, the southern Indian state of Kerala has been negotiating how to invest to enable people to survive well. Rather than applying a business-focused investment strategy (with the benefits expected to trickle down), Kerala has invested directly in people’s well-being. Health has been one area of investment. Some 94 percent of births are attended by health professionals and the infant death rate is lower than that for African Americans in Washington DC. The total fertility rate is two births per woman and the population growth rate is below replacement level. As a result, Kerala does not have an abnormal female to male sex ratio. In India as a whole this ratio is 91 women to 100 men. In Kerala, for every 100 men there are 109 women. Education is another priority area. Along with investment in schooling for boys and girls there have been adult literacy projects (including ones focused on rural areas). As a result, Kerala has a 90 percent literacy rate. One implication of this investment pathway is that Kerala has a skilled workforce but not the jobs to match. This leads many educated Keralites to seek employment overseas. And although physical health has improved across the board, there are mental health problems reflected in the high suicide rate. This example reflects how building a community economy is an ongoing process that involves negotiating the dilemmas that arise.

Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer

With concerted international action on climate change progressing slowly, what can we learn from other efforts to common open access resources such as the atmosphere? In 1985, what become known as “the hole” in the ozone layer over Antarctica was detected, promoting more understanding of the negative impacts on surviving well; two years later, in 1987, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was agreed to and came into force in January 1989. Rapid action resulted, not just from the work of nation states and their negotiators, but from the efforts of a “community of concern” that formed to common the ozone layer (including scientists, unionists, multinational corporations, media reporters, and ordinary citizens). Rapid action also resulted after a period of seeming inertia: concerns about the effects of ozone-depleting chemicals (ODCs) had been raised since the early 1970s, but once “the hole” was detected and captured in images, action swiftly followed. By 2005, the Montreal Protocol had resulted in a 95 percent reduction in the production and consumption of ODCs by all 191 countries that ratified the Protocol. This case offers some hope that a global commoning of the life-sustaining layers of the earth’s atmosphere could occur through the development of appropriate rules and protocols.

Strategies for Cultivating Community Economies

CEC has developed strategies to help cultivate community economies. The first strategy activates a politics of language to describe economic diversity and bring existing ethical economic practices to visibility. The second suite of strategies activate both a politics of the subject (by helping to generate a range of new subject positions), and a politics of collective action. The aim here is to broaden the horizon of economic politics so that ethical economic practices might multiply.

Strategy 1: Situating Existing Economic Politics within a Diverse Economy

Our first strategy uses a language of the diverse economy to expand the scope for economic action and legitimate economic politics across a broad front. Language (in textual and visual forms) plays a crucial role in generating new ways of seeing and acting. Currently, the language of economy is dominated by an essentialist vision of capitalism; wage labor, commodity production for markets, profit-seeking capitalist enterprise are seen as the real economy. Our anti-essentialist and non-deterministic language of economy destabilizes this dominant representation of the economy as singularly capitalist.

Our anti-essentialist and non-deterministic language of economy destabilizes this dominant representation of the economy as singularly capitalist.

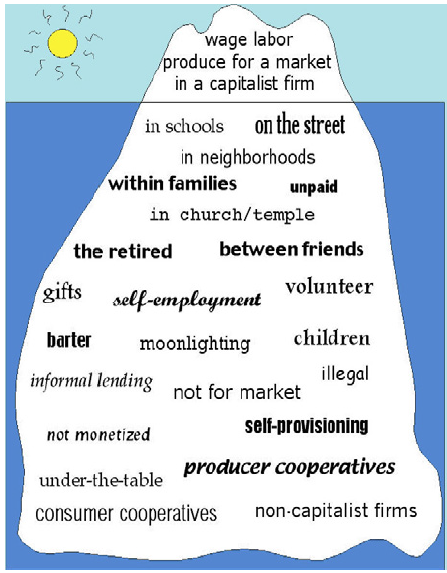

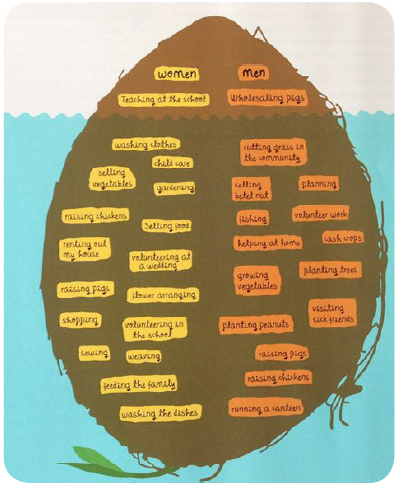

A vast and varied array of economic practices sup-port lives in the world. We have used the Diverse Economy Iceberg as one way of representing how substantive economic practices are far more diverse than what is captured by mainstream economics. Economies involve a wide range of people, processes, sites, and relationships. What is usually referred to as “the economy” is just the tip of this diverse economy iceberg.

The language of the diverse economy allows us to identify actually existing spaces of negotiation and to demonstrate how saying that we live in a capitalist world or a capitalist system is to negate the ways that other possible worlds are already all around us. Within a diverse “more than capitalist” economy, we can discern multiple pathways that are being used to build these other possible worlds. We approach these examples, not with a judging stance, but with an open stance to the possibilities they contain.

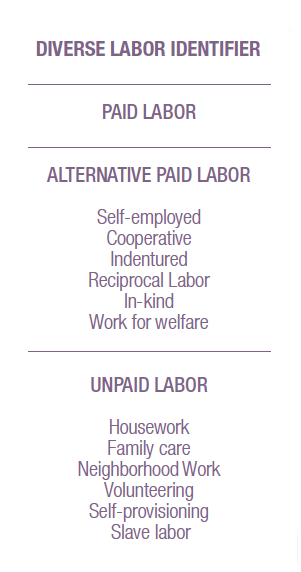

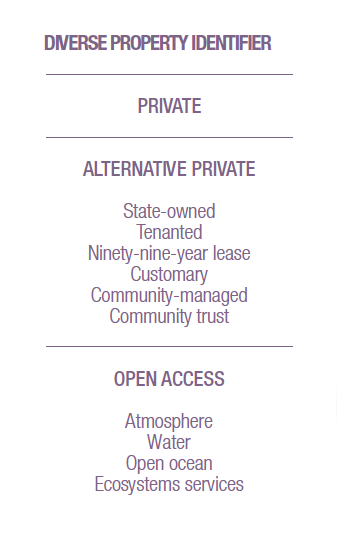

One way we promote a language of economic diversity is through the use of five identifiers related to work, business, markets, property, and finance. Within each identifier, we include a range of economic practices including familiar or mainstream practices (from a Western perspective); those that have some of the characteristics of the mainstream but with a twist (e.g. labor payments that are in-kind; green capitalist firms); and those that fall well outside of what is usually considered “economic” (e.g. volunteer work, or gifting).

The purpose of these identifiers is twofold. First, they draw attention to the economic diversity that is already present in this world. This means they feature practices that by their very nature are imbued with ethical commitment (e.g. cooperatives, fair and direct trade); those that are neutral but with the potential to be imbued with an ethical commitment (e.g. household flows, sweat equity); and those that are immoral (e.g. slavery and feudalism). Second, by drawing attention to this diversity, the intention is to help identify economic practices that might serve as building blocks for a community economy. Thus, the identifiers are prompts to help us see the possibilities that are all around, and are triggers for conversation and discussion. We do not operate within a realist epistemology that claims to “capture reality” and tries to be comprehensive or definitive.

Here it is worth noting that the identifiers are “works-in-progress.” Initially we used the categories of labor, enterprise, and transactions; more recently, we have added property and finance. Crucially, it is not a matter of getting the categorization right. Indeed, we recognize that the process of categorization is deeply problematic. We are currently exploring other ways of representing economic diversity that is not “boxed in” but makes space for recognizing how these practices are messy, fragmented, contradictory, and unstable.

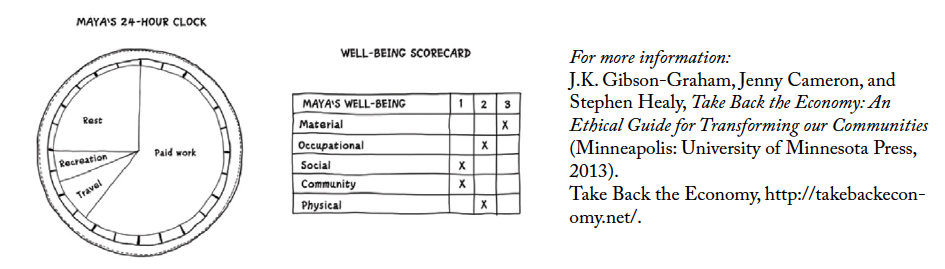

The Politics of Work: Surviving Well Together

There are a variety of labor practices that people use to survive. In a community economy, we consider not just how these practices might enable an individual or household to survive, but how these practices impact on other people and on the environment. For example, we know that the reliance on paid work in the minority world (sometimes called the developed world) has resulted in an emphasis on material well-being to the detriment of other types of well-being—social, community, spiritual, and pysical. There are also flow-on effects. Reliance on paid work has encouraged a pattern of unsustainable consumption that negatively impacts on other people and environments.

The diverse labor identifier helps pinpoint the practices that might be pursued by households, communities, and civic institutions to improve well-being for people and planet.3 For example, would reducing the amount of time spent in paid labor and substituting paid labor with other types of labor (such as self-provisioning and volunteering) provide not just material well-being but also social, community, spiritual, physical, and environmental well-being? This is certainly the wager of those who are redefining work through a variety of initiatives—from individuals who are downshifting (or increasing their overall quality of life through strategies such as cutting back on paid work, changing to lower paid but less stressful jobs, moving to less expensive regions), to groups involved in the simplicity living movement, employers who support the 30/40 workweek and NGOs who are lobbying for a 21-hour workweek.

Reliance on paid work has encouraged a pattern of unsustainable consumption that negatively impacts on other people and environments.

As another example, we can use the diverse economy identifier to “think through” the current experiments in Basic Income Grants pursued by states in both the minority and majority world. These grants contribute directly to survival at the household level. But by providing a guaranteed basic income, these potentially also free up time and resources that could be repurposed—towards civic engagement, care of social and environmental commons, even contributing to creativity and innovation.

Other types of actions that are important in this domain include:

- Campaigns for fair work and wages (such as living wage and anti-sweatshop campaigns).

- Government inputs that help everyone survive (such as universal healthcare, free education, affordable housing, public transport, carers’ payments, paid maternity and parental leave).

- Initiatives for sharing the things that help us to survive (such as cohousing, car pooling, food sharing).

These actions certainly connect with established political movements; however, these movements tend to focus on one type of labor activism (unions—wages and conditions for paid labor; anti-slavery movements—abolition of slavery; small business organizations—conditions for self-employment). In a community economy what gets negotiated is the interconnection between different struggles. For example, what impact do increased wages in one sector or nation have on working conditions in other sectors or nations? Or in other settings such as the household? Similarly, what are the consequences of these actions for planetary well-being?

The Politics of Business: Distributing Surplus to Increase Well-being

There are a variety of business or enterprise types that generate new wealth (or what is also known as surplus). The most familiar enterprise type is the capitalist enterprise in which workers produce surplus value that is then appropriated and distributed by the capitalist owner.4 We are interested in the conditions under which surplus is generated, who makes decisions about surplus, and how the surplus is distributed. In a community economy: 1) surplus is produced in safe and fair working conditions (and we recognize this as part of the conditions of survival, discussed above); 2) the decision making about surplus is democratic and involves those who produced the surplus; and 3) the surplus is distributed in ways that contribute to social and ecological well-being.

Worker-owned cooperatives are a standout example of enterprises in which the workers who produce the surplus also make decisions about how the surplus is to be distributed. Generally, these cooperatives have a strong social and environmental ethos, which means that surplus is distributed in ways that are oriented to the well-being of others. So in a community economy, worker-owned cooperatives are important, as are the organizations that promote and support the development of these cooperatives, such as the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, The Working World, the Australian Business Council of Cooperatives and Mutuals, and Solidarity Economy initiatives. Also important are networks of cooperatives such as Mondragon Corporation, Evergreen Cooperatives, and the Network of Bay Area Cooperatives.

But there are other enterprise politics that can play a role in a community economy:

- Employee Stock Ownership Programs (ESOPs), which can be a means of transitioning to more participatory forms of enterprise through a process of democratizing ownership.

- Social enterprises, which directly address social and environmental well-being (and which are becoming more prevalent through legal forms such as the Community Interest Company in the UK).

- More ethical forms of capitalist enterprise, which direct surplus towards social and environmental well-being (and which are becoming more prevalent through a range of associations that promote social and environmental responsibility in capitalist businesses, e.g. B Corps; Business Alliance for Local Living Economies; the Economy of Communion; and the Relational Business Charter).

As illustrated by the Community Interest Company in the UK, there are institutional shifts that can help promote and support the development of more ethical enterprises. Changes to the taxation system can also be an important incentive (such as how Italian and Spanish tax legislation favors the development of cooperatives).

The Politics of Markets: Encountering Others through Diverse Transactions

Capitalism and markets are frequently conflated by champions and critics alike. Anti-market forces bemoan “commodification” of the life world, while market champions decry the market distorting effects of social and environmental regulation and activist interference. The conflation of markets with capitalism marginalizes all of the ways that goods and services have been and continue to be exchanged between proximate individuals and across disparate communities. In a community economy what gets negotiated is how all parties (including nonhuman others) are affected by the process of exchanging goods and services, inside the market and out.

By identifying different forms of transactions we can see all the ways individuals and communities exchange things in order to survive.5 We can inquire into the ethical negotiations involved: how might exchange relationships support individuals and communities in both giving and receiving? How might ecological and social concerns be valued and accounted for in the context of market-based and other exchange relationships?

Mainstream markets are woven into the cultural fabric of many societies. Particularly in minority world cultures, the supermarket and discount stores play to our senses and appeal to our thriftiness. They also help us to avoid thinking too deeply about how the things we buy so cheaply are produced or what happens to the things we discard. However, as Annie Leonard points out in Story of Stuff, contemporary consumer culture has shallow roots—a couple of generations of time.6Could it be that consumers are developing new habits—using new markets to connect with places and one another, using peer-to-peer exchange networks to recycle all manner of goods and services? Could it be that we are developing spaces of ethical connection and negotiation? Some of the ways we see this happening include:

- The expansion of ethical markets, at a localized scale, that take into account the well-being of others, reflected, for example, in the growth of farmers markets and other buy local initiatives, and ethical buying guides.

- The expansion of ethical markets, at an international scale, that take into account the well-being of others, reflected, for example, in the growth of fair and direct trade networks.

- The expansion of ethical reciprocity that now takes a variety of forms such as community supported agriculture (and its spread into new areas such as community supported fisheries, yoga, per-forming arts), complementary currencies and principled discarding through the use of Freecycle and other networks.

The Politics of Property: Commoning Diverse Resources

The dominant discourse in the minority world has been that promotion of private property is the most efficient and just way to use and conserve things of value. One of the tropes used for the past two generations to justify this assertion has been Garrett Hardin’s infamous phrase, “the tragedy of the commons,” a phrase which was based on a fictitious grazing field that is ruined as individuals, pursuing their own self-interest, despoil the commons. Decades later, Hardin admitted that the “weightiest mistake” was not adding the word “unmanaged.” The tragedy was the lack of practices of care and management of the commons, not the commons as such. It has been up to researchers such as Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom to document how communities have developed complex norms and practices to manage common resources, in some cases for centuries.

In a community economy people talk to one another, they develop protocols or rules that govern the access and use of resources, they collectively exercise responsibility to care—for land, water, forests, fisheries, intellectual property, educational and health systems, languages, and much else. Looking at the rules around the use and care of commons changes our understanding from a noun (commons are simply there) to a verb (commoning is something we do to care for what we use and value, without necessarily owning it).7

Identifying different forms of property allows us to see how people are developing social relations of commoning across a range of tenure, such that commoning practices are divorced from forms of tenure.8 These include:

- initiatives to common private property (such as voluntary conservation agreements that are used by private landholders to protect land from development, in perpetuity, or efforts to remunicipalize water or sewerage systems that have been privatized);

- initiatives to common open access resources such as the atmosphere (the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer discussed above is one example, others include the Nauru Agreement Concerning Cooperation in the Management of Fisheries of Common Interest);

- efforts to resist enclosure by defending existing common resources (ranging from the work that was done in the 1990s to ensure the Human Genome Project was a scientific commons to current legal struggles to maintain Antarctica and outer space as terra communis).

The Politics of Finance: Investing in Futures

In the past decade, the unstable and speculative nature of the global financial system has been revealed. Many have “paid the price” for loosening the financial rules and agreements put in place after the Second World War. Only “the one percent” seem to have benefited, with the disparity in the distribution of wealth burgeoning over the last decade. Given this backdrop, it is perhaps in the area of finance that it is hardest to find possibilities of community economies—but there is evidence that communities are investing surplus to address current challenges and build a common future. These range from contemporary online innovations such as crowdsourcing to the application of more traditional forms of financial support such as informal rotating savings groups. With these types of investment strategies it becomes possible to move financial thinking away from short-term speculation towards more carefully considered and future-oriented investment.

By identifying diverse forms of finance we become aware of the multiple monetary and non-monetary resources that might be marshalled to secure better social and ecological well-being for the present and the future.9 Once we recognize this diversity we can inquire into the ways that communities are accessing diverse forms of finance, and particularly the shifts to policy and legislation that would make it easier for enterprises, organizations, and communities to invest in a common future. This is why entities that are innovating with financial tools are so important (with such entities including the Chantier de l’économie sociale, Québec (discussed above), Charity Bank in the UK that lends to charities and social enterprises, and the community banking movement in Australia).

Other ways that communities are innovating with investment opportunities include:

- Peer-to-peer financing in which people directly invest in helping each other to build their future. Such initiatives include traditional Rotating Credit and Savings Organizations (ROSCAs), the pooling of migrant remittances as a form of capital for alter-native development pathways, and more contemporary forms of online financial support.

- Do-it-yourself financing whereby groups generate their own finances and resources. This can range from community-issued scrips and community investment notes to the use of reciprocal labor as a form of capital.

- Ethical investment including both investment in ethical funds and divestment in harmful activities (with the current push for institutions such as universities to divest from fossil fuels).

- Redirecting government revenue towards life-sustaining rather than life-destroying activities, including using tax revenues for social infrastructure and environmental initiatives.

Strategy 2: Broadening the Horizon of Economic Politics

Our anti-essentialist approach encourages us to broaden the horizon of what constitutes economic politics. For us, transformation can occur over various temporal frames and geographic scales, and as a result of actions both organized and disorganized (and even as a result of non-human actions). Just as there are a diversity of economic practices, there are a diversity of political possibilities. In our own work, we have been inspired by the ways in which social movements around feminism and sexual identity have remade society. In an astonishingly short period of time (two and a half generations or so), these movements have transformed the meaning of gendered and sexual identity, and thereby transformed how lives are being lived (and the movements continue to change lives). These social movements illustrate how thinking and acting differently in discreet locations can have global consequences. They also highlight the value of a form of politics that “connects the dots” between seemingly small and isolated actions and “scales them out” through processes of adaptation, translation, and reinterpretation. These processes inform our second strategy of broadening the horizon of economic politics.

This understanding of change also means we have a distinctive take on more familiar forms of economic politics. When the economy is framed in terms of capitalism, and when capitalism is presented as spreading across the globe, it seems that it has to be matched by an equivalent anti-capitalist struggle organized globally. This diminishes the potential of the local as a site of economic politics. However, when the economy is framed as comprising diverse practices this opens up multiple sites as places of economic struggle. It also destabilizes what we mean by global and local. What seems global is actually multiple locals; likewise, what seems local can be globally networked and connected.

Strategies for broadening economic politics build on the first strategy of activating a politics of language to help shed light on diverse and ethical economic practices. Here the attention shifts to a politics of the subject and ways in which an expanded language of the economy might be used to help people recognize themselves as economic agents with the capacity to enact economic change through a politics of collective action.

In what follows we provide examples of how this approach to multiple and intersecting forms of politics has been variously deployed by us, starting with what we have at hand as researchers based in university settings. This is our contribution to economic politics and we are interested in how it connects with the political activities of others, including other academics, grassroots activists, artists, policy makers, and so on.

Action Research

The CEC has developed methods of action research for generating alternative economic development pathways in places and regions where mainstream economic growth has faltered. Academic and community researchers, principally local residents, work with other local residents, particularly those most marginalized by capitalist development, to coproduce new social enterprises, community supported production and marketing, and commons management.

Community Partnering 1

In an action research project in the Australian mining and power resource region of the Latrobe Valley (1999-2000), we combined the language of diverse economy with asset-based community development. This helped to reframe retrenched workers, unemployed youth, and needy welfare recipients as people with multiple gifts of the head, hands, and heart. It also helped to reframe a supposedly problem-beset region as having an array of physical, associational, and people assets that might be the basis of a new economic development pathway. Supported by a series of workshops and field trips, local residents (including those employed on the project as community researchers) built a small cluster of community-based initiatives. This project was funded by the Australian Research Council and Latrobe City Council. The method was then used with groups of residents from marginalized neighborhoods on the urban fringe of Brisbane, Australia (2002 to 2004).10

Community Partnering 2

Building on the methods developed in Community Partnering 1 this action research project was situated in two poor, labor-exporting, rural communities in the central Philippines. Local residents, supported by community researchers, university researchers, and NGO representatives, worked together to establish community-based social enterprises. The website developed from this project offers training tools for people and organizations interested in developing local economies by: putting people first, building on local assets and strengths, forming new partnerships, experimenting with forming social enterprises, and extending networks of support. This project was in partnership with Unlad Kabayan Migrant Services Foundation Inc., and was funded by the Australian Research Council and AusAID.11

Hybrid Collective Research Method

Drawing from the experiences of Community Partnering 2 (and the Networking Community Food Economies project, discussed below), we have refined the action research approach to recognize how human and non-human others can work together as acting subjects. We describe this method as being based on three critical interactions: gathering, which brings together those who share concerns about an issue; reassembling, in which material gathered is rebundled to amplify particular insights; and translating, by which reassembled ideas are taken up by other collectives so they may continue to “do work” in the world.12

Collaborative mapping

CEC members have worked with community researchers using Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping techniques to bring to visibility the number and spatial extent of ethically informed economic activities. This strategy has been used to highlight solidarity economies, urban and marine commons.

Mapping the US Solidarity Economy

This project identified the spatial distribution, impact, and significance of solidarity economy practices in the US. It collated national data and produced an interactive map of solidarity entities including producer, worker, and consumer cooperatives, credit unions, cooperative housing, and other entities that emphasize shared solidarity economy values. The project focused on solidarity economy activities in three US cities—Philadelphia, New York, and Worcester, Massachusetts. In these cities researchers produced more detailed maps and explored the distribution of solidarity activity in relation to demographic features. They also used economic modelling to quantify the impact of solidarity economy activity, and conducted interviews to understand the cultural and political significance of solidarity economy entities at the municipal and state scales. The project was supported by the National Science Foundation.13

Commons Sensor App

Commons-sensor is a mobile friendly website developed by open-local and the Parramatta Collaboratory. The sensor allows citizen researchers to enter photographic, quantitative, and descriptive data about the physical, cultural and knowledge commons around them, recording how commons are accessed and used but how responsibility for care is allocated to ensure commons-continuity. The sensor uses “open street maps” as a base map (also a commons) so it is adaptable to many locations throughout the world.14

Re-claiming Marine Commons through Participatory Mapping

This project used participatory mapping techniques to engage fishing communities in the Northeast US concerning their use and stewardship of marine resources. The “Atlas Project,” funded by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration through the Northeast Consortium, asked fishing community members to map and give meanings (cultural, historical, environmental, and economic) to those areas at sea upon which their communities depended. Community-based mapping exercises visually linked coastal economies and consumption practices to at-sea fishing grounds, habitats, and ecosystems and in so doing fostered a rethinking of fishers and fish themselves as interdependent elements of a local marine commons and community economy. This work has developed new standards for mapping “communities at sea” that can be used as a novel data layer for fisheries management and Marine Spatial Planning.15

Assemblage Research

Assemblage research acknowledges the role of non-humans and materiality in world-making processes. It also recognizes that the local and global are outcomes of particular networks and associations rather than inherent qualities or capacities. The CEC has developed projects that attempt to include the more-than-human as actors and as potential allies in the creation of community economies. These projects involve tracing and creating connections of association between what is traditionally seen as discrete, isolated, or local with other processes and practices elsewhere.

Reassembling Marine Livelihoods in the Northeast US

In the Northeast US CEC researchers have engaged fishing communities, marine scientists, and fisheries policy makers to create a new assemblage around concern for human and non-human community sustainability. Present and future community and commons livelihoods have been prioritized by this assemblage in a number of new initiatives. One has seen the formation of the nation’s first community-supported fisheries (CSF) initiative in Port Clyde, Maine that links together consumers, fishers, and the marine commons through a direct marketing scheme similar to community supported agriculture (CSA). There are now over thirty CSFs in the US. Another has seen coastal communities rethinking local production, services, and utilities as commons resources open to inventive solutions (e.g. community owned wind energy, cooperative marketing practices, and shared broadband access). Importantly, the assemblage has inserted a “communities at sea” sensibility into research on community adaptation as marine resources shift location due to climate change.16

Urban Agroecology Assemblages in the Philippines

Current research in Manila and urban Mindanao is examining urban agroecology initiatives, where people are working with typhoons, rivers, plants, vegetables, “waste” materials, and digital media to grow different ethical economic food futures. This research is highlighting how people, materials, and more-than-human forces can work together to create more liveable worlds.17

Resilience Assemblages in Monsoon Asia

When economic crisis or disaster hits Monsoon Asia, a raft of economic practices such as sharing, reciprocity, and resource pooling come to the fore as part of the recovery and relief effort. In this new project (2015 – 2017), we are interested in shedding light on cases where these economic practices have been innovatively harnessed to diversify livelihoods, and build economic and ecological resilience. The project is highlighting the ways that human and nonhuman materialities and subjectivities have worked together effectively to strengthen resilience.18

Developing New Metrics

Indicators and metrics measure and count “what matters.” But many contemporary indicators reduce the complexity of social life to bare numbers that can be used for neoliberal means of governing. The CEC is interested in developing the progressive potential of indicators and metrics. We do this with a grounded approach that generates discussion of lived practices and works with users so that their experiences are incorporated.

Taking Back the Economy

This book offers a reframing of the economy and contains inventories, metrics, and accounting frameworks that prompt self-reflection and learning to be affected by human and earth others. In every dimension of the economy—work, business, markets, property, and finance—new and existing technologies of measuring and accounting are presented to highlight the ethical dimensions of economic decision making. For example, in the realm of work, the personal metrics of work time and well-being are juxtaposed with the impact on planetary well-being via their ecological footprint.

Place-based Indicators for Gender Equity and Economic Change

In partnership with NGOs and community groups in Solomon Islands and Fiji, this project aimed to generate a Pacific-based understanding of gender equity. It sought to widen the understanding of the economy and better represent diverse Pacific ways of life and livelihood. To do this, the gendered division of labor was shown on the diverse economy, here represented as a floating coconut, rather than an iceberg. The research developed culturally grounded community level indicators that track gender equity impacts of economic change and development programs.19

Shifting Manufacturing Culture

This new project (2016–2018) is about manufacturing in Australia, and it is based on case studies of manufacturers who are “doing business” in innovative ways (e.g. environmental responsibility, employee participation and/or social inclusion). The case studies cover a range of sectors (from food production to metalworking to materials reuse), and a range of business types in terms of size and organizational structure (including social enterprises, cooperatives, and green capitalist). The research will document how the manufacturers are contributing to dimensions such as well-being, purposeful work, ecological care, and wealth sharing. One outcome will be a series of metrics that pinpoint the types of contributions made by innovative enterprises, and that unpack the decision making that lies behind these contributions.20

Learning to be affected

CEC researchers are involved in creating connections and encounters that offer new ways of learning to be affected by entities and forces in the world. Here we are building on the work of Bruno Latour and others who have advanced a post-humanist vision of agency. If open to doing so, bodies/beings can learn from the entirety of human and non-human conditions of the world that affects us. This process of co-constitution produces new body-worlds who may be capable of living in the world differently, more lightly, less exploitatively.

Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene

We acknowledge the tragedy of anthropogenic climate change. It is important to tap into the emotional richness of grief about extinction and loss without getting stuck on the “blame game.” Our research allows for the expression of grief and mourning for what has been and is daily being lost. But it is important to adopt a reparative rather than a purely critical stance toward knowing. Might it be possible to welcome the pain of “knowing” if it led to different ways of working with non-human others, recognizing a confluence of desire across the human/non-human divide and the vital rhythms that animate the world? The essays in this Manifesto focus on new types of ecological economic thinking and ethical practices of living.21

Guarding Life through Alternative Hygiene Practices

Mothers and other caregivers in China, Australia, and New Zealand learn to be affected by babies’ signs and signals for impending “elimination”— the reducing or removing the need for diapers. For some, this is a way of“guarding life” (a literal translation of the Chinese ideograms for hygiene) for babies’ health; and for others, a way of guarding life for people and planet by enabling changes around diaper usage and waste.22

Networking Community Food Economies

Through a field trip based research method, a group of community gardeners visited each other’s gardens to learn more about the nascent network of community gardens across Newcastle, Australia. The project brought to the fore the ways in which the embodied practice of community gardening (through which gardeners were learning to be affected by climate change) was contributing to both a climate politics and a post-capitalist food politics.23

Reading for Difference

In the modern development imaginary, diverse economic practices have been positioned as “traditional,” “rural,” and largely superseded. By reading against the grain of modernization, CEC scholars bring diverse economic practices into visibility, making them accessible in a range of sites as an asset to be mobilized by community members, policy makers, and development practitioners.

Reading for Cooperation in Post-Soviet Russia

This research investigates diverse non-capitalist economic practices and property relations that have developed in Russia in the last two decades, despite policy efforts to build private property and a capitalist economy. It examines the complexity of economic and social relationships within Russian and migrant households, indigenous communities, and industrial and agricultural enterprises. By reading for difference, it aims to identify economic practices of cooperation that support livelihoods and are aimed at avoiding exploitation. The research analyzes the class, gender, and racial/ethnic dimensions of these grounded ways of establishing economic and social justice and solidarity.24

Reading for Difference in Forest Ecologies and Economies

CEC researchers have worked with local communities in the Northeast US and in Scotland to document how local ecological knowledge is used in the gathering of wild plants and fungi. This work centers on acknowledging and validating different forms of environmental knowledge rather than integrating local knowledge into scientific discourse. The goal is to demonstrate how diverse forest practices involve ethical decision making around care of the environment and thereby contribute to human-non-human community building25

Reading for Postdevelopment Practices

Several parallel projects by members of the CEC are engaging critically with development practice and offering insights into new ways to practice development that sidestep some of the harmful effects of mainstream development practice. Highlighting examples of place-based and politically engaged modes of development practice offers pathways towards new forms of professional engagement.26

Reframing

Drawing on insights from psychoanalytic practice, we have used techniques of reframing that give new meaning and value to people’s lives, and might prompt a willingness to explore collective actions.

Reframing Our Economies, Reframing Ourselves

The Rethinking Economy project sought to reframe the economy to illuminate the hidden, alternative and non-capitalist activities in the Pioneer Valley Region of Western Massachusetts. The project was undertaken by a research team that included academic and community researchers and was funded by the National Science Foundation. In the process of reframing the economy, the team struggled with the familiar vision of capitalist dominance and sense of powerlessness it engenders. Research training became a form of intervention through which the team began to feel more comfortable with both the uncertainties and possibilities of non-capitalist spaces, relationships, and processes—and our own self-sense as economic subjects.27

Reframing Care

In a new project to rethink maternity care through community economies, researchers are engaged in reframing economies of care in maternity and early childhood. Entrenched ideological conflict between the medical and natural birth paradigms interferes with efforts to provide good care. This project aims to craft a shared context and language with women and care providers that will chart a pathway out of the partisan conflict. It uses digital ethnographies and deliberative forums to explore and transform the social, economic, and material relationships that make good care possible. Working with a wide range of stakeholders to coproduce new understandings of what it takes to care well, this project aims to contribute to ensuring that mothers and children not only survive, but survive well.28

Reframing Disaster

The 2010 and 2011 earthquake sequences in Christchurch, New Zealand devastated the city’s central business district. The empty and unsafe buildings were reduced to piles of rubble contained behind temporary fencing. Once the rubble was cleared and the fences dismantled, the emptied lots were turned into gravel parking spaces awaiting the prolonged rebuild. This is not the only story to be told about Christchurch’s city landscape. The earthquake sequences were also a time of great innovation and community action, and the central business district was also the site of quirky, cooperative creative arts and solidarity economy transitional projects that brought people together during this difficult time. This project attempts to tell this different story, alongside similar stories of creative arts “commoning” in New Zealand.29

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3g5TDNgEVqM

Endnotes

| 1. | ↑ | This document has been written by J.K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, Kelly Dombroski, Stephen Healy, and Ethan Miller on behalf of the Community Economies Collective. Sections of Strategy 2 have been contributed by additional members of the CEC. |

| 2. | ↑ | Other intellectual and political traditions that we draw upon include Socialism, Anarchism, Radical Democracy, Queer Theory, Ecological Humanities, Science and Technology Studies, Political Ecology, and Indigenous Studies. We are interested in working with the enabling features that each of these traditions/epistemologies offers. |

| 3. | ↑ | The diverse labor identifier includes “regular” paid work, i.e. workers who are remunerated via wages and salaries; other forms of “paid” work (e.g. self-employed workers who pay themselves, cooperative members who set their own wages, workers paid in-kind and those who must complete work tasks in order to receive a welfare payment); and “unpaid work” in its various forms. |

| 4. | ↑ | The diverse enterprise identifier includes the familiar profit-maximizing capitalist enterprise, but also businesses that distribute profits to benefit those beyond the enterprise (e.g. capitalist firms that enact green practices and state-owned enterprises). It also includes enterprises that are non-capitalist (in that the surplus that is produced is appropriated and distributed by someone other than a capitalist, for example by the workers who also own the business, or by the individual owner-operator of the business). Again, it is not a matter of getting the categorization right—the aim is to draw attention to the variety of enterprise types and ways of producing and distributing new wealth. |

| 5. | ↑ | The diverse transactions identifier includes “regular” market-based transactions as well as those that use the market in different ways. For example, fair and direct trade produce is transacted via markets that are based on shortening the supply chain and “distorting” the pricing mechanism so that producers benefit. Local trading systems are also a form of a market but based on a different currency (including time as the currency system). We also include nonmarket-based transactions. |

| 6. | ↑ | Annie Leonard and Ariane Conrad, The Story of Stuff: How our Obsession with Stuff is Trashing thePlanet, our Communities, and our Health—and a Vision for Change (New York: Free Press, 2010). |

| 7. | ↑ | We acknowledge the important work done by David Bollier on commoning, including his contribution to the Next System Project: David Bollier, “Commoning as Transformative Social Paradigm,” The Next System Project, 2016, http://www.thenextsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/DavidBollier.pdf . |

| 8. | ↑ | The diverse property identifier draws attention to property relations. It includes “regular” individually-owned private property, as well as other forms of private property such as state-owned propertyor property that is tenanted in various ways, or property that is owned according to customary practices. In all of these forms of property, relations of inclusion and exclusion are at work. The final category therefore highlights property that is open access (while also recognizing that therehave been and continue to be pressures to enclose or privatize these resources). |

| 9. | ↑ | In the diverse finance identifier we identify mainstream market-based finance provided by the banking system. There are also other forms of banking and financing that overlap with market-based operators. For example, credit unions conduct the same type of business but they are member rather than shareholder owned. Microfinance initiatives lend money as do market-based operators but with very different terms and conditions. We also identify a range of nonmarket based financial mechanisms such as donations and rotating loans schemes. Again, it is not a matter of determining what type of finance belongs where in the categorization; rather, the intention is to open up various forms of finance for discussion and conversation. |

| 10. | ↑ | For more information: Jenny Cameron and Katherine Gibson, “Alternative Pathways to Community and Economic Development: The Latrobe Valley Community Partnering Project,” Geographical Research 43, (2005): 274-285. Jenny Cameron and Katherine Gibson, Shifting Focus: Pathways to Community and Economic Development: A Resource Kit, Victoria, Canada: Latrobe City Council & Monash University, 2001, It’s in Our Hands: Shaping Community and Economic Futures (documentary), School of Environmental Planning, Griffith University. Production by J. Cameron, with S. La Rocca and D. Monson, 2003, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1r_h9GeV2Q & https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptLjXNECrFs. |

| 11. | ↑ | For more information: Katherine Gibson with Ann Hill, “Community partnering for local development,” 2010, http://www.communi-typartnering.info. Community Economies Collective and Katherine Gibson, “Building Community-based Social Enterprises in thePhilippines: Diverse Development Pathways.” In The Social Economy: International Perspectives on Economic Solidarity, edited by Ash Amin (London: Zed Press, 2009). Building Social Enterprises in the Philippines: Strategies for Local Development (fifty minute DVD), Production by Katherine. Gibson, Ann Hill, Paul Maclay, and M.A. Villalba, 2009. Online at www.communityeconomies.org. |

| 12. | ↑ | For more information: Jenny Cameron, Katherine Gibson, and Ann Hill, “Cultivating Hybrid Collectives: Research Methods for Enacting Community Food Economies in Australia and the Philippines,” Local Environment, Special Issue on Researching Diverse Food Initiatives 19, 1 (2014): 118-132. |

| 13. | ↑ | For more information: US Solidarity Economy Map and Directory, http://solidarityeconomy.us/.“About,” Mapping the Solidarity Economy, https://mappingthesolidarityeconomy.wordpress.com/.“What is the Solidarity Economy?”, Solidarity Economy Resources, http://cborowiak.haverford.edu/solidarityeconomy/. |

| 14. | ↑ | For more information: Commons Sensor, Commons-sensor.openlocal.org.au. Commons Sensor, Holland, commons-sensor-holland.openlocal.org.au. |

| 15. | ↑ | For more information: Kevin St. Martin, “Toward a Cartography of the Commons: Constituting the Political and Economic Possibilities of Place,” Professional Geographer 61, 4 (2009): 493-507. Kevin St. Martin and Madeleine Hall-Arber, “Creating a Place for ‘Community’ in New England Fisheries,” Human Ecology Review 15, 2 (2008): 161-170. Kevin St. Martin and Madeleine Hall-Arber, “The Missing Layer: Geo-technologies, Communities, and Implications for Marine Spatial Planning,” Marine Policy 32 (2008): 779-786. |

| 16. | ↑ | For more information: Kevin St. Martin, and Julia Olson, “Creating Space for Community in Marine Conservation and Management: Mapping Communities at Sea,” in Conservation in the Anthropocene Ocean, edited by Phillip Levin and Melissa Poe (Amsterdam: Elsevier, forthcoming 2017). Robert Snyder and Kevin St Martin, “A Fishery for the Future: The Midcoast Fishermen’s Association and the Work of Economic Being-in-Common,” in Making Other Worlds Possible: Performing Diverse Economies, edited by Gerda Roelvink, Kevin St Martin, and J.K. Gibson-Graham (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). Island Institute, www.islandinstitute.org. Local Catch, www.localcatch.org. “A Good Catch,” The Nature Conservancy, http://www.nature.org/magazine/archives/a-good-catch.xml. |

| 17. | ↑ | For more information: Ann Hill and Jojo Rom, “From Calamity to Community Enterprise,” Asian Currents, May (2011): 7-9, http://www.communityeconomies.org/site/assets/media/AnnHill/asian-currents-11-05.pdf. Ann Hill, “Growing Community Food Economies in the Philippines,” (PhD diss., Australian National University, 2013). |

| 18. | ↑ | For more information: Projects, “Strengthening Economic Resilience in Monsoon Asian,” Western Sydney University, http://www.uws.edu.au/ics/research/projects/strengthening_economic_resilience_in_monsoon_asia. J.K. Gibson-Graham, Ann Hill, and Lisa Law, “Re-Embedding Economies in Ecologies: Resilience Building in More than Human Communities,” Building Research & Information 44, no. 7 (October 2, 2016): 703–16. |

| 19. | ↑ | For more information: Katharine McKinnon, Michelle Carnegie, Katherine Gibson, and Claire Rowland, “Generating a Place-based Language of Gender Equality in Pacific Economies: Community Conversations in the Solomon Islands and Fiji,” Gender Place and Culture (2016), Published online, DOI: 10.1080/0966369X.2016.1160036. Michelle Carnegie, Claire Rowland, Katherine Gibson, Katharine McKinnon, Jo Crawford, and Claire Slatter, Monitoring Gender and Economies in Melanesian Communities: A Manual of Indicators and Tools to Track Change, 2013, http://www.iwda.org.au/research/measuring-gender-equality-outcomes-economic-growth-pacific/. |

| 20. | ↑ | For more information: Projects, “Reconfiguring the Enterprise: Shifting Manufacturing Culture in Australia,” Western Sydney University, http://www.uws.edu.au/ics/research/projects/reconfiguring_the_enterprise_shifting_manufacturing_culture_in_australia. |

| 21. | ↑ | For more information: Katherine Gibson, Deborah Bird Rose, and Ruth Fincher, eds., Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene (Goleta, CA: Punctum Books, 2015), https://punctumbooks.com/titles/manifesto-for-living-in-the-anthropocene/. |

| 22. | ↑ | For more information: Kelly Dombroski, “Multiplying Possibilities: A Postdevelopment Approach to Hygiene and Sanitation in Northwest China,” Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 56, 3 (2015): 321-334. Kelly Dombroski, “Hybrid Activist Collectives: Reframing Mothers’ Environmental and Caring Labour,” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 36, 9/10 (2016), 629-646, doi:10.1108/IJSSP-12-2015-0150. |

| 23. | ↑ | For more information: Jenny Cameron, (with Craig Manhood & Jamie Pomfrett), “Bodily Learning for a (Climate) Changing World: Registering Differences through Performative and Collective Research,” Local Environment, 16, 6 (2011): 493-508. Newcastle Community Garden Project, A Community Garden Manifesto, Compiled by Jenny Cameron (with J. Pomfrett), Centre for Urban and Regional Studies, University of Newcastle, 2010, http://www.communityeconomies.org/site/assets/media/Jenny_Cameron/Manifesto_Small.pdf. |

| 24. | ↑ | For more information: Marianna Pavlovskaya, “Post-Soviet Welfare and Multiple Economies of Households in Moscow,” in Making Other Worlds Possible: Performing Diverse Economies, edited by Gerda Roelvink, Kevin St. Martin, and J.K. Gibson-Graham (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). Marianna Pavlovskaya, “Between Neoliberalism and Possibility: Multiple Practices of Property in Post-Soviet Russia,” Europe-Asia Studies, 65, 7 (2013): 1295-1323. |

| 25. | ↑ | For more information: Elizabeth S. Barron, “Situating Wild Product Gathering in a Diverse Economy: Negotiating Ethical Interactions with Natural Resources,” in Making Other Worlds Possible: Performing Diverse Economies, edited by Gerda Roelvink, Kevin St. Martin, and J.K. Gibson-Graham (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). Marla Emery and Alan R Pierce, “Interrupting the Telos: Locating Subsistence in Contemporary US Forests,” Environment and Planning A, 37 (2005): 981-993. |

| 26. | ↑ | For more information: Katharine McKinnon, Development Professionals in Northern Thailand: Hope, Politics and Power, ASAA Southeast Asia Publications Series, Singapore University Press in conjunction with University of Hawaii and NIAS, 2011. Katharine McKinnon, “Diverse Present(s), Alternative Futures,” In Interrogating Alterity: Alternative Economic and Political Spaces, edited by Duncan Fuller, Andrew E.G. Jonas, and Roger Lee (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Press, 2010). |

| 27. | ↑ | For more information: Community Economies Collective, “Imagining and Enacting Noncapitalist Futures,” Socialist Review, 28, 3 & 4 (2001): 93-135. Stephen Healy, “Traversing Fantasies, Activating Desires: Economic Geography, Activist Research and Psychoanalytic Methodology,” Professional Geographer, 62, 4 (2010): 496-506. |

| 28. | ↑ | For more information:Kelly Dombroski, Katharine McKinnon, and Stephen Healy, “Beyond the Birth Wars: Diverse Assemblages of Care,” New Zealand Geographer (2016), Early View, doi/10.1111/nzg.12142. Stephen Healy, “Caring for Ethics and the Politics of Health Care Reform in the United States,” Gender, Place and Culture, 15, 3 (2008): 267-284. Katharine McKinnon, “The Geopolitics of Birth,” Area (2014), published online, doi: 10.1111/area.12131. |

| 29. | ↑ | For more information: “New forms of commoning in a post-quake city,” “ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3g5TDNgEVqM |

________________________________________

J.K. Gibson-Graham is a pen name shared by feminist economic geographers Katherine Gibson and the late Julie Graham (Professor of Geography, University of Massachusetts Amherst). Katherine Gibson is currently a research professor at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Australia. Books by J.K. Gibson-Graham include The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy (1996); Class and Its Others, eds. J.K. Gibson-Graham, S. Resnick, and R. Wolff (2000); Re/presenting Class: Essays in Postmodern Marxism, eds. J.K. Gibson-Graham, S. Resnick and R. Wolff (2001); A Postcapitalist Politics (2006); Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming our Communities by J.K. Gibson-Graham, J. Cameron & S. Healy (2013); Making Other Worlds Possible; Performing Diverse Economies, eds. G. Roelvink, K. St. Martin, and J.K. Gibson-Graham (2015); and, Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene, eds. K. Gibson, D. Bird Rose, and R. Fincher (2015).

Jenny Cameron is an Associate Professor in geography and environmental studies at the University of Newcastle, Australia. Her work focuses on the development of so-called economic alternatives such as cooperatives and community enterprises. With J.K. Gibson-Graham and Stephen Healy she is author of Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming our Communities (2013). She teaches courses on global poverty and development, globalization, and geographies of development. She is a keen backyard and community gardener, and is currently on the board of directors of her local organic food cooperative.

Kelly Dombroski is a lecturer in human geography at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. Her research gathers around the themes of everyday life and social change, particularly with regards to rethinking the ways that we live with the earth, in light of resource depletion, climate change, and unequal access to the necessities and pleasures of life on earth. Recent work includes “Hybrid Activist Collectives: Reframing Mothers’ Environmental and Caring Labour” in the International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, and “Seeing Diversity, Multiplying Possibility: My journey from Post-feminism to Postdevelopment with JK Gibson-Graham,” in W. Harcourt (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development.

Stephen Healy is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Australia. His work focuses on the relation-ship between economy, subjectivity, and the enactment of new econo-socialities exploring various topics: health care reform policy, the role of cooperatives in regional development, and the solidarity economy movement. His most current research project (with Katherine Gibson, Jenny Cameron, and Jo McNeil) is supported by the Australian Research Council and is focused on the role that cooperatives, social enterprises, and ecologically oriented enterprise might play in reconfiguring manufacturing. His most recent publications include Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities, co-authored with Jenny Cameron and J.K. Gibson-Graham (2013).

Ethan Miller is a Lecturer in politics, anthropology, and environmental studies at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. His current work focuses on challeng-ing problematic distinctions between “economy,” “society,” and “environment” in regional development processes, and on developing cross-cutting and integrative conceptual tools to strengthen transformative, postcapitalist organizing efforts. Ethan has also been engaged for the past fifteen years with an array of projects focused on cooperative and ecological livelihood, including the Data Commons Cooperative, Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO), the JED Collective cooperative homestead, and Land in Common community land trust.

Go to Original – nextsystem.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.