On Caring

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 29 May 2017

Prof. George Kent – TRANSCEND Media Service

Author George Kent feels the theme of caring needs more attention and analysis because of its importance in all social contexts. This is a prepublication draft of his paper, “On Caring”. It was published in Michelle Brenner, ed., Conversations on Compassion. Sydney, Australia: Holistic Practices Beyond Borders, 2015. The published version can be accessed at http://www2.hawaii.edu/~kent/OnCaring.pdf. He used “On Caring” as the foundation for his recent book, Caring About Hunger. It was published by Jørgen Johansen’s Irene Publishing. It is available through http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/johansen_jorgen and through other online publishers.

Wondering about Caring

2015 – Many of us who work on large-scale social problems become engrossed in the dark side of human behavior, studying things like violence, poverty, hunger, and other social pathologies. We begin to see these things as common, even inevitable. We look for remedies for these phenomena when they occur, and rarely consider that maybe they need not occur. Instead of just studying war and hunger, we should also give attention to how peace and plenty might work.

Most people most of the time treat each other rather nicely. Surely, caring must be a central element. We do that without fanfare. Caring is so common, we don’t see it.

In Mutual Aid, Peter Kropotkin pointed out that people usually treat each other well, helping each other out in countless ways.[1] Social scientists have little to say about this good quality in human relations. It is as if they have forgotten the social in social science. Thus, the literature on hunger analyzes the problem as if it afflicted only individuals and households in isolation, not recognizing that people, especially people with low-incomes, do a lot to take care of one another.

Thinking in terms of conventional economic analysis can make people less caring.[2] That framework is driven by the idea of individual accumulation of wealth, but this is not always the dominant motivation. In reality, people share resources in many different ways, and many people refuse to be stunted by the compulsive desire for endless accumulation. There are some forms of economic analysis that do not make the wrong-headed assumptions we learn in Introductory Economics classes. Analyses of the gift economy, for example, are based on the understanding that people tend to be generous to one another. So far the alternative ways of thinking about economics have not displaced the dominant economic mythology.

This essay is about caring, defined as acting to benefit others. More specifically, it is about empathetic caring, the caring that is rooted in our capacity to share others’ feelings. Caring in this sense is about action taken for the purpose of benefiting others.

Caring is about empathy that goes beyond merely cognitive understanding of how others feel to also include an emotional impact:

It is feeling sad in response to another’s sadness; joy in response to another’s joy; fear in response to another’s fear, and so on. So conceived, empathy transfers others from external objects into parts of ourselves; “different” consciousnesses not only interact, they interpenetrate. In this way empathy expands our identity to include others; what happens to them, in some measure, happens to us.[3]

With caring, your well-being is linked to and affected by others’ well-being. Their feeling good makes you feel good, and their feeling bad makes you feel bad.

Empathetic caring should be distinguished from instrumental caring, the kind that is offered in exchange for some direct benefit to oneself. Empathetic caring is its own reward. Caring that is viewed primarily as a means for obtaining benefits for the carer is instrumental caring.[4]

In organized business-like caring, usually there is a clear distinction between those who have needs and those who provide caring for them, as in a care home. In natural caring, there is no structural distinction between those who provide care and those who receive it. With strong mutual caring, there is much less need for deliberately designed caring by specialists. Often, increasing needs for caring interventions by specialists are signs of the weakening of natural caring in the community.

At times instrumental caring becomes mechanistic, done by a “caretaker” mainly because he or she is paid to do it. Instrumental caring is based on self-interest, while empathetic caring is based on concern for the well-being of another. Instrumental caring is not bad, but we should recognize that it is different from empathetic caring.

Often, caring acts are undertaken for mixed motives, partly to benefit another, and partly to benefit oneself. For example, the Fonterra dairy company in New Zealand explains that it provides free milk to school children “because we believe it will make a lasting difference to the health of New Zealand’s children[5],” but elsewhere the company “admits it’s also about promoting its product, and lifting falling milk consumption.”[6] Apparently Fonterra distributes free milk to improve children’s health and also to improve its long-term profits. There is nothing wrong with doing both at the same time. We often do things for several different reasons.

At times there are good reasons for cynicism. Along with promoting milk consumption at home and in other parts of the world, Fonterra is promoting the use of infant formula, especially in Asia. In that context, it does not mention that this profit-motivated push is likely to result in worse health outcomes for millions of infants.[7] In other contexts, we see manufacturers marketing foods to children with blatant disregard for their impact on children’s health.[8] The widespread tendency of the food industry to prioritize their profits over consumers’ health sends a message about their caring priorities.[9]

Some writers define altruism as “behavior carried out to benefit another without anticipation of rewards from external sources.”[10] That is the same as what is described here as empathetic care. There is no reason to insist that empathetic care requires self-sacrifice. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with drawing benefits for oneself at the same time one acts to benefit others. Many people who are called to do good things for others enjoy their calling immensely. The empathetic caring part is almost always good. The self-interest part should be assessed on its own merits.

Caring and compassion seem to be closely related. However, some analysts define compassion as “the feeling that arises in witnessing another’s suffering and that motivates a subsequent desire to help.”[11] In the perspective adopted here, caring is not necessarily triggered by suffering. The abundant caring behavior observable in ordinary daily life is not only in response to suffering.

Caring may be related to cooperation. However, cooperation often implies making a deal. It can be understood as a type of investment. Treating others well in cooperative endeavors is commonly explained by the idea that it leads to some sort of reward, whether here or hereafter. Business people often cooperate because they feel they can make more profit by working together rather than separately. At times cooperation turns into collusion or conspiracy, which are about cooperation at the expense of some third party.

Some writers analyze cooperation specifically in situations in which individuals seek to maximize their self-interest.[12] One book devotes a section to the point that cooperation is not altruism.[13] Cooperation that is driven primarily by self-interest is what we have described as instrumental caring. It is different from empathetic caring, which is about doing things for the purpose of benefiting others.

In the perspective adopted here, empathetic caring does not have to be explained in terms of its producing some sort of material advantage for oneself or one’s group. Indeed, the concept of deal-making demeans that type of caring. Mother Teresa and Saint Damien did not care for the homeless and the sick in exchange for an anticipated payoff.

This essay is primarily about empathetic caring. It should be made more visible so its importance can be recognized. This essay wanders through the idea of caring and wonders about it, beginning with the more familiar types, and then pushes the envelope to explore less familiar types. There is caring for one another, for animals, for things, for our ancestors, for the planet, for the cosmos. They are all somehow connected together, and that connectedness is both mysterious and important. The purpose of this journey of exploration is to come to a deeper appreciation of how it is that we care and thus act to benefit others—other people and other things–and to find ways to increase that caring.

Caring Individuals

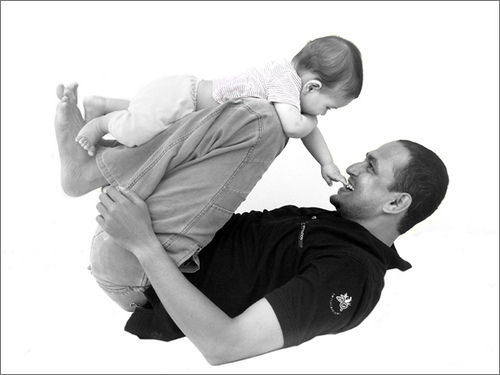

Caring can be a simple and beautiful thing, as illustrated here.

Figure 1. Caring: Father and Child.

Source: https://c2.staticflickr.com/4/3474/3762206605_f176511859.jpg

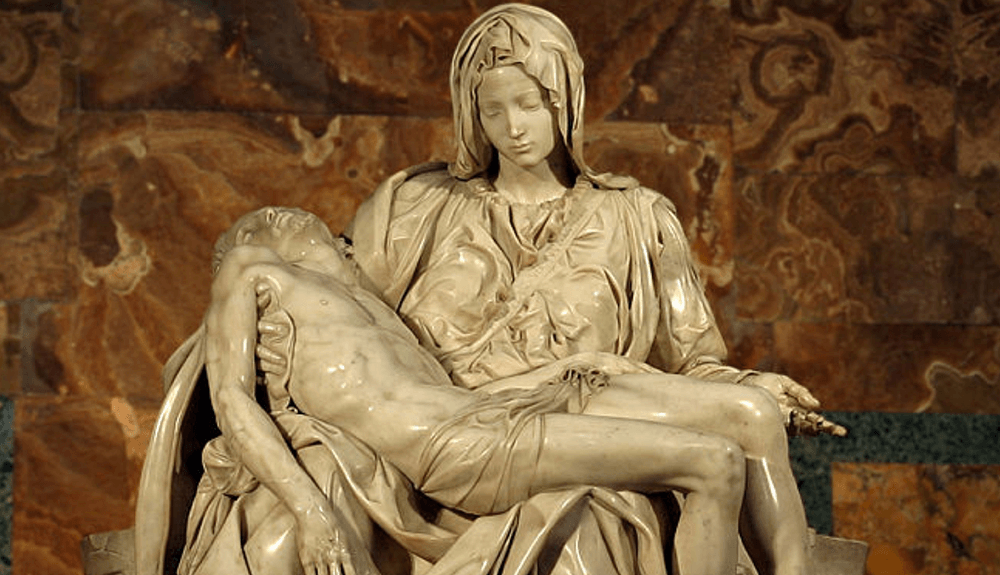

There are also deeper multi-layered representations of caring, like that in Michelangelo’s Piéta.

One doesn’t need to know about Christianity or the fact that that statue has an honored place in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome to see and feel that it is about caring. Michelangelo was so powerful as an artist that his portrayal transcends imagery of two specific people to instead represent caring in all of humankind.

Types of Human Relations

Simplifying, we can distinguish three major types of human relations:

- Caring, in which people feel better off when other individuals are better off, and thus act to benefit others;

- Indifference, in which people do not care about others’ well being, and thus do not act to help them or to harm them; and

- Exploitation, in which people benefit from others’ misery. An employer who pays his workers as little as possible is exploitative. A consumer who buys cheap products from ruthless manufacturers could be seen as an exploiter. Sadists get pleasure from others’ misery. Germans have a special term, schadenfreude, for “enjoyment obtained from the troubles of others.”[14] We can include in this category the pleasure a general might feel in defeating an enemy, or a coach might feel when his team defeats an opposing team. Rapists and pornographers are exploiters. Exploiters draw benefits from hurting others.

Exploitation is often done for what are claimed to be good reasons. You might hire low-wage workers for your business so that you can provide more comforts for your family. You might kill others to protect your country. You might accept “collateral damage” from a bombing run because you calculate that the benefit of killing “militants” outweighs that cost. You might discriminate against people of certain races in order to protect your own.

People weigh and balance things differently. We don’t all navigate by the same moral compass. Whether intentionally or not, we often benefit from actions that harm others. Caring and exploitation can be tied together in complex ways.

Caring, indifference, and exploitation are broad and crude categories, but they convey useful distinctions. They are comparable with the distinctions others make among givers and takers.[15] [16]

The two previous images represent caring. Figure 3 illustrates indifference.

Figure 3. Indifference: Hungry Child.

Source: http://budapestbeacon.com/featured-articles/20000-hungarian-children-starving/

We don’t see who it is that is indifferent. It could be the child’s family, or maybe the child’s community, or the government of that child’s country. It might be that some of them are not indifferent, but simply do not have the capacity to relieve that child’s plight. The fact that many parents in Haiti send their children to orphanages shows that some parents are unable to support their children.[17] However, we do know that the global community, taken as a whole, has no such excuse. In 2013, global wealth reached an all-time high of US$241 trillion, up 4.9% from the preceding year.[18] The world certainly has the capacity to feed hungry children. It cares, but not enough.

Globally, child mortality rates have been declining rapidly, but there are still more than six million children who die before their fifth birthdays each year. Most of these deaths can be attributed to global indifference rather than to any sort of direct abuse or exploitation.

Indifference is important. Many people suffer various forms of neglect, oppression, and violence and get no attention from the rest of the world. This is not only about how rich countries treat poor countries. Many countries with means are indifferent to the poor and powerless segments of their own populations. In Korea, suicides of people over 65 have increased sharply because their children no longer care for them adequately.[19] India has been among the world’s leading exporters of rice and beef, and it exports substantial amounts of wheat and other food products, while at the same time, a large part of its population suffers from serious malnutrition. Contrary to the image the United States presents of itself, almost half its people live in poverty.[20] In India and the U.S., the poor do get substantial subsidies from the government, but these programs seem to hold people in poverty rather than helping them climb out of it. One of the major impacts of the subsidies for the poor is that they ensure a steady supply of cheap labor for the benefit of the rich.

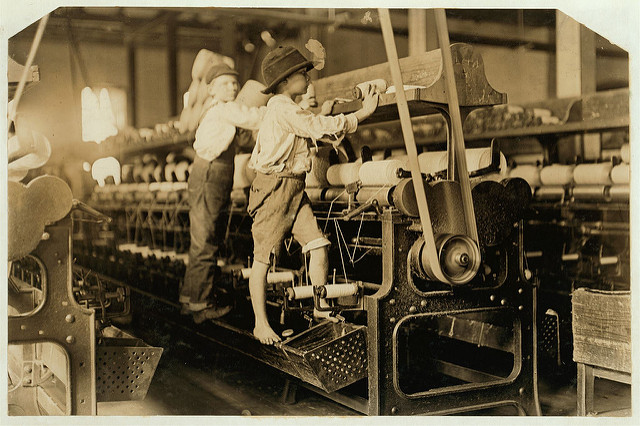

In situations of economic exploitation, like that illustrated in Figure 4, much of the value produced by people’s labor goes to benefit others, leaving the workers in marginal conditions. They are deprived not only in terms of income but also in terms of their dignity and their identity as distinct individual personalities.

Figure 4. Exploitation: Child Workers.

Source: https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/192/484535150_a6f1e82065_z.jpg

Indifference and exploitation are important, but the focus here is on caring.

Sometimes caring takes on heroic proportions, as illustrated by war heroes and saints. We should also notice and appreciate ordinary everyday caring. The caring of individuals for other individuals is often expressed in simple acts such as offering others a few words of encouragement or even just listening to others’ concerns. In a way, it is too bad that schools teach children about super-heroes like Mother Teresa, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, placing them on sky-high pedestals. That elevation to heroic Nobel-prize status might make it appear that caring is out of reach for us ordinary flawed mortals, when in fact it is the stuff of everyday life, and within everyone’s capabilities. This essay is not about caring as a heroic rescue mission, but caring as a way of living together with others. We need to honor ordinary caring. It is the glue that holds civil society together.

Individuals, organizations, and governments at all levels may show caring in routine decisions. This is because they recognize that many of their decisions affect the well-being not only of themselves but also of others. In deciding which chocolate bar to buy, one should consider how that choice would affect the people who make it.

Often it is difficult to obtain all that information and to assess likely impacts on others, so those considerations are ignored. But sometimes the information is right there, and still we ignore it. That is, we might not care much about those impacts on others.

Every decision says something about decision-makers’ priorities and their concerns for others. When a report on global agriculture showed that production yield levels of some of the world’s major food crops have been declining, one of the co-authors, Jonathan Foley, said,

This finding is particularly troubling because it suggests that we have preferentially focused our crop improvement efforts on feeding animals and cars, as we have largely ignored investments in wheat and rice, crops that feed people and are the basis of food security in much of the world.[21]

Every farmer and every manufacturer must make choices about what he or she will produce, just as every seller must choose what to sell, and every consumer must choose what to buy. In every action, each of us must make our own decisions regarding what we care about. Our decisions all add up to shape what it is that we as individuals, and also our social systems, care about.

Quantifying Caring

There have been good efforts to design measures of well-being.[22] Assessing the degree to which someone cares about others’ well-being is a more difficult matter.

The degree to which a person cares about people and things can be assessed on the basis of the choices they would make in different circumstances. A person who likes vanilla ice cream more than chocolate chooses vanilla. The choice reveals the person’s priorities. One way to estimate what individuals or agencies care about is to look at their budgets. If a community spends much more on football than on children’s health, we have an important indication of what it cares about. We can get clues not only from the allocation of money but also from the allocation of attention. If a country does not collect data on the nutrition status of its children, it is not likely to do anything about it.[23] If the local media devote more space to stock market reports than to genocidal conflicts on the other side of the world, we have indications of what those media and their audiences care about.

Caring for another person’s or group’s well-being means making choices partly on the basis of how they affect that other person or group, and not solely on the choice’s direct impact on oneself. Conceptually, the degree or intensity of caring could be estimated by assessing the extent to which an individual is willing to forego a benefit in order to deliver a given amount of benefit to another.

While caring does not always require sacrifice, the intensity of caring is indicated by the willingness to give up benefits to oneself in order to ensure benefits to others.

In strong caring communities, people would be willing to give up things in order to take care of their neighbors, whether those things were money or time or something else. This positive caring would ensure the health of the community as a whole.

It is difficult to actually measure and study caring in quantitative terms, but the concept is important. Caring, acting to benefit another is essential to a well-functioning social order.

Caring Within and Among Communities

Caring is important to human well-being in every kind of community.[24] It is especially important for those with low-incomes, and thus more dependent on the people around them. A poor person living among equally poor but caring people will have a much better quality of life than someone with the same income level living in an indifferent or exploitative community.

We tend to assume that people who have money are always happy, and those who don’t have much money must be miserable. These assumptions certainly are not correct. People get a great deal of satisfaction out of their social interactions. There are many communities that do quite well despite their operating outside the dominant money exchange system.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu described the importance of group solidarity in this way:

Africans have a thing called ubuntu. It is about the essence of being human, it is part of the gift that Africa will give the world. It embraces hospitality, caring about others, being willing to go the extra mile for the sake of another. We believe that a person is a person through other persons, that my humanity is caught up, bound up, inextricably, with yours. When I dehumanize you, I inexorably dehumanize myself. The solitary human being is a contradiction in terms. Therefore you seek to work for the common good because your humanity comes into its own in community, in belonging.[25]

The theme was pursued at a conference held in Johannesburg in July 2013:

The theme of the event, “Caring Cities”, is based on the concept of Ubuntu, an African ethic or humanist philosophy focusing on people’s allegiances and relations. Caring Cities are cities that strive to offer a high quality of life, showing a sense of humanity and exchange, providing comfort and dignity for all citizens and deliver solutions that meet the needs of their citizens.[26]

The importance of strong communities became clear to me while writing Ending Hunger Worldwide. I said:

Free trade among self-interested individuals might be important for maximizing economic growth, but strong communities are the best instruments for achieving human development.

Karl Polanyi observed, “It is the absence of the threat of individual starvation which makes primitive society, in a sense, more humane than market economy, and at the same time less economic.”[27] This is another way of saying that in strong communities, where people care about one another’s well being, people don’t go hungry. As we can see in India, the United States, and many other places, economic growth does not necessarily end hunger. Caring may matter more than economics.

An individual’s being isolated and destitute, possibly on the streets, is a signal that there are problems not only for the individual but also for the community. Both challenges need to be addressed. In strong, well-functioning communities, people take care of each other. There is a depth to this care that goes far beyond mailing off a check to a worthy organization or dropping a few dollars into a beggar’s cup. Sometimes it is a matter of being there for a person in need, and listening to their story…

Local self-reliance, food sovereignty, and democracy are good, but something more is needed. Hunger results mainly from poverty and the effects it has on people’s diets. This takes place in a social context. The extent to which people suffer from hunger and other forms of malnutrition depends on how they treat one another.[28]

The hunger problem is not only about deficits in land or seeds or skills or markets. Those technical things may be important, but in the end the central issue is the deficit in caring. There are deficits of caring from rich to poor, but also in caring from neighbor to neighbor. In strong communities, where people care about one another’s well-being, no one goes hungry. That is generally true in poor communities as well as rich communities. In caring communities, no one goes hungry unless everyone goes hungry, as might happen in a disaster situation.[29]

Caring gestures can play important roles in defusing intense armed conflict situations. Sometimes they take peculiar twists, as in a counter-insurgency effort in India in October 1993:

In Srinagar, which is the capital of the State of Jammu & Kashmir, terrorists took over the most sacred mosque in the city . . . . The security forces laid siege to the mosque without actually attacking it in order to prevent damaging it. The attempt was to starve out the terrorists. Meanwhile someone sent in a Writ petition to the Jammu & Kashmir High Court stating that this was violative of the fundamental rights of the terrorists. The High Court decreed that the besieging forces could not inflict starvation on the terrorists and, therefore, they were directed to see that two full meals were sent into the mosque for its occupiers every day. It is only in India that we could have a situation in which the police and the army sent in two huge containers of food at noon and at sunset so that the terrorists could feed themselves.[30]

The terrorists were seen as part of the community, deserving a measure of care.

Even if caring gestures do not bring an end to armed conflicts, they can be helpful. Moves in the right direction can inspire others to do the similar things. This is well illustrated by the history of the Red Cross. Demonstrating right action can be worthwhile even when it does not lead to clear strategic victories. For example, the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, created by Daniel Barenboim and the late Edward Said, has for decades helped to bring together young people from all sides of the Middle East conflicts.[31] There is another more recent initiative within Israel called the Polyphony Youth Orchestra.[32] Joint activities of this sort may not have huge impact in terms of peacemaking, but they demonstrate the possibility of civility between the parties. Sometimes we do things because they are the right things to do, not because they will be measurably effective in achieving some goal.

Social scientists should give more attention to the qualities of communities. Which are strong in the sense that people care about one another? Which are permeated by exploitative relationships? Which communities are marked by large-scale indifference to the poor or to other groups such as ethnic minorities or people with disabilities? Unfortunately, there are no well-developed indicators or data collections that offer good insight on the quality of human relationships in communities. This is an important and much neglected issue.

Strong communities serve as good protection not only from hunger but also from poverty, crime, violence, pollution, and many other negative aspects of modern life. Strong communities can provide remedies when such problems occur, but more importantly, they can prevent the problems from ever occurring.

Hunger will not end as a result of missions sent to feed the hungry, but by finding ways of living together that prevent hunger and other miseries from ever occurring. Many individuals and agencies have done hugely important work in rescuing people from hunger, but the prevention of hunger will come from the regular day to day concern of people for their neighbors.

Caring among individuals is commonly experienced within communities. The caring tends to be strongest in small face-to-face groups, but it can also extend to much larger groups such as nations, spanning large stretches of both space and time. How far can we expect caring to reach? Surely no one expects that we could care for very different sorts of people on distant continents as much as we would care for our own families and our own ethnic and religious groups. We simply cannot care for others who are distant geographically, chronologically, and socially in the same way we care for those who are close to us.

There are limits to caring, and counter-pressures that must be plainly recognized. In any intense, sustained conflict, one’s acting together with people from the other side can be viewed as traitorous. This has been obvious in the Irish troubles, the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab conflicts, and many other situations. Often increasing one’s connections with others can mean loss of connection with one’s own people. This is why, in many hard conflicts, the two-state solution is best, with stable separation rather than common community. Instead of hoping for some sort of integration between the conflicting parties, it may be better for them to live apart, with arrangements that deter attacks or other de-stabilizing actions between them. Stable, respected boundaries are important means for protecting distinct groups.

Despite limits to our capacity for caring, we should care to some degree for all people who face extreme hardship and injustice, no matter how distant they might be.

A reasonable moral precept for dealing with distant communities is, at the very least, to do no harm. We cannot be expected to feed all those who are hungry in distant lands, but we should at least be sure to not take food or anything else away from them. In particular, we should not take the fruits of their labor to such an extent that they remain impoverished and unable to provide for themselves.

We should support the idea of social and economic safety nets, systems through which limits are placed on how far any person’s well-being is allowed to decline. Local and global safety nets should be established, and over time they should be lifted to higher levels.[33]

Animals and Plants

We have used the terms caring, indifference, and exploitation to describe relationships among people, but they also can be applied to other kinds of relationships. For example, many people act in a caring way to protect land, water, and animals in nature, even when those acts do not return any direct benefits to the actor. We recognize the exploitation of nature where people deplete and pollute their environment. Some farmers mine the soil and the water, making them unavailable for future generations, some fishers take too much, and some hikers wantonly destroy trees and trails, spoiling them for those who follow.

There are abundant examples of people being caring, indifferent, or exploitative toward animals. There are also many examples of animals treating people in those ways. Many animals display caring behavior to humans, often in homes, but also in other contexts. There are many examples of animals rescuing people in distress, inspiring many lists of such caring events.[34] [35] [36]

There is clear evidence of caring among animals.[37] [38] Scenes of obvious caring are presented in photographs by Scientific American magazine.[39]A TV news story showed an extraordinary situation in which a lion, a tiger, and a bear lived and played together for years.[40]

Some animals show signs of grieving when their mates or friends die.[41] Surely this is a manifestation of caring. “Grieving profoundly . . . is the price humans pay for caring profoundly.”[42] That concept also applies to animals.

Caring among animals of the same species is commonplace, but caring across species is more interesting. We see it often in homes that have both cats and dogs. In some cases the two species merely co-exist, as separately as they can, but in others they interact actively and even affectionately.

Caring is more surprising when it happens between species of very different kinds, such as a cat and a bird [43] or a rat and a cat.[44],[45] YouTube has many examples of inter-species connection, including some in the wild. These species are not “all one”, but despite their diversity, they get along.

Some animals have uncanny skills in caring for humans. There are many stories of cats and dogs that seem to be able to detect when a person is ill or in pain. Many are “employed” in hospitals and care homes, as therapy animals.

Sometimes caring by animals for humans is not motivated by the animals’ concern for the well-being of the humans, but is more of a business deal. The Eden Killer Whale Museum in Australia tells the story of a pack of killer whales that for decades helped to herd and kill baleen whales for the benefit of local human whalers. The trade-off was that the whalers would leave specific tasty parts of the baleen whales for the killer whales to feast on.

What about plants?

There is a film that says forest plants live in communities of a sort, doing things to benefit one another.[46]

In an article on “The Intelligent Plant,” Michael Pollan discussed forest communities.[47] He pointed out that when some types of closely related plants are placed in the same pot, they restrain their usual competitive behavior and instead share resources. Some researchers think corn plants show evidence of altruistic behavior.[48] Can plants really live in communities and demonstrate altruistic or caring behavior?

Do the plants really care about one another, or is this merely a metaphor? What is the difference?

Artifacts and Nature

We often draw lines between human-made artifacts and things in nature, but sometimes the boundary is not so clear. One basis for drawing the distinction is the idea that things in nature can have motivations, but inanimate things cannot. But maybe we make too sharp a distinction. We know cats and dogs have motivations because they can be observed doing things that are obviously goal-directed. However, for other life forms, the point is not so clear. Do bacteria have motivations? What about plants? Is it sensible to say that a bridge, a building, or a tool has a purpose of its own, independent of the users’ purpose? Or is it better to just say these things are useful to us humans?

Cars can be much more than just tools for getting from one place to another. Some people spend more money on dressing up their cars than on dressing their children. The uses of things often go beyond simple usefulness.

Is this idolatry? Is it simple anthropomorphism, attributing human qualities such as motivations to inanimate things? Is this just a matter of mislabeling things, or should ideas like “care” and “purpose” be understood as having broader meanings than we are used to giving them? Pantheistic religious perspectives often speak of objects having their own inner purposes.

Just as we can care for nature, we can also care for artifacts such as bridges, buildings, canoes, and aquaculture ponds. We can be awestruck by beautiful cathedrals just as we can be awestruck by beautiful valleys. Transcendent experiences, often marked by moments of awe, have something to do with caring. Both are about being in touch with something beyond oneself.

Clearly, people can care for nature. But does nature also take care of people in some active sense? Or do we simply try to adapt to a wholly indifferent, mindless nature?

These concerns can be framed in terms of the Gaia perspective, the view that “humanity constitutes a living system within the larger system of our Earth”[49]:

Take the living system most intimately familiar to all of us: the human body. We’ve long known that our bodies behave as a community of cells, which are organized into organs and organ systems. The central nervous system functions as the body’s government, continually monitoring all its parts and functions, ever making intelligent decisions that serve the interest of the whole enterprise. Its economics are organized as an equitable system of production and distribution, with full employment of all cells and continual attention to their wellbeing. The immune `defense’ system protects its integrity and health against unfamiliar intruders. It can be thought of as a kind of global political economy with organs as bioregional units, their different tissues as communities, cells as families or clans, and the organelles within cells as individuals.

Physiologically we can see that the needs and interests of individual cells, their organs and the whole body must be continually negotiated to achieve the body’s dynamic equilibrium or healthy balance.[50]

From this perspective it makes sense to speak about the “metabolism of cities” and the ways in which cities meet their needs.[51]

There has been a good deal of advocacy for recognition of legal rights of animals, as illustrated by the Nonhuman Rights Project.[52]

Why draw the line at animals, and not talk about legal rights for other things? Some scholars have argued in favor of legal rights for natural objects. The underlying idea is that objects in nature, and maybe even artifacts, have intrinsic interests, apart from the usefulness they might have to humankind, and therefore the legal system should protect them.[53] [54] In Aotearoa (New Zealand), this concept has been implemented by recognizing a river as a legal person, and thus having rights.[55]

As people care for the environment around them, that environment also cares for them, in a sense. This is not a matter of simple reciprocity, as in a deal to cooperate. It goes deeper than that, a kind of unspoken symbiosis among elements in a shared system, organs in an organism. This dimension of the terrain of caring is difficult to explore, involving concepts that may be alien or even alienating. It is one thing to suggest that the earth and the cosmos are alive in some sense, involved in some sort of dynamic organic flow, as in Gaia thinking. It is another huge step to suggest that there is something akin to consciousness in that environment. And still another step to feel and believe that this disembodied consciousness cares about the well-being of you and me.

There are interrelations among the different types and levels of caring. Caring for another person or an animal or a plant may be a spiritual act, at least for some people. Some people care for the corn or the taro they grow not simply for the nourishment it provides, but also for the contact it allows with another dimension of the world, one that is alive in its own way.

One manifestation of long-distance caring is international humanitarian assistance to people in need, coming from governments or from non-governmental organizations. The long historical arc of international humanitarian assistance is documented in Michael Barnett’s The Empire of Humanity, ranging from the antislavery and missionary movements of the nineteenth century to disaster assistance and peace-building efforts in modern times.[56] Frequently, the motives behind these operations have been mixed, as they often are in relation to caring acts at the personal level. Unfortunately, international humanitarian assistance often falls far short of what is needed.[57]

We tend to think of caring in terms of personal relations, with family and neighbors, and with our local environment. But sometimes we see that caring is important for the larger whole, all of humanity, all of the world, and maybe all of the cosmos. These are transcendent forms of caring, going well beyond what we see and experience directly.

Some people say, “we are all one”, but what does that mean? It cannot mean we are all the same because we are not. People are different from one another, and from cats and birds. We should take this “we are one” to mean that we are all important parts of a larger whole, just as the organs of the human body are parts of a larger whole. The parts don’t always get along well with each other, but getting along certainly is a compelling recommendation. We ought to care for the whole, through space and also through time.

As parts of the larger whole, we can think of the organs of the human body as wanting to take care of their host. In much the same way, we can think of the earth and its environment as being, in some sense, motivated to take care of the human residents. Some scientists dismiss this sort of thinking as “promiscuous teleology”.[58],[59] People with a more spiritual orientation would be inclined to dismiss those scientists.

Caring has been defined here as acting to benefit others. Many things in nature and many different kinds of artifacts provide benefits to people. Does this mean they care? Is the essence of caring in the action, or the thought behind the action, the underlying intention?

Does it matter whether the idea of motivation in animals or inanimate objects is viewed as a fact or a metaphor? Ideas don’t have to be true to be useful, as we learn from imaginary numbers and Aesop’s fables. Scriptures of various kinds survive not because their stories have proven true but because they have proven useful. Some people argue that nature does not really care about us,[60] but it makes sense for us to treat nature as if it did.

Ideas of the sort discussed here might seem strange, but they have been spreading and growing in many quarters. They reached a high level when, “On April 22, 2013, in commemoration of International Mother Earth Day, the UN General Assembly hosted its third annual interactive dialogue on Harmony with Nature.”[61] There is now a United Nations website on Harmony with Nature.[62]

Past and Future, and Spirit

We commonly talk about caring for people and things as if they were here and now, but there are important space and time dimensions to caring. We tend to care more for people who are closer to us, physically, culturally, temporally, spiritually, and on other dimensions as well.

People care not only for what is here and now and also for things from the past and the future. Some people give constant attention to their ancestors, and in many cases also to the g-dly precursors of their human ancestors, all honored in their creation stories. They also give attention to their descendants, and do a great deal for them. This occurs not only at the family level but also at the community and cultural level.[63]

The idea of “paying it forward” embodies the idea of caring projected into the future. For example:

Imagine a restaurant where there are no prices on the menu and where the check reads $0.00 with only this footnote: “Your meal was a gift from someone who came before you. To keep the chain of gifts alive, we invite you to pay it forward for those dine after you.

That’s Karma Kitchen, a volunteer-driven experiment in generosity.[64], [65]

People who are interested in establishing sustainable social systems care about the well-being of people and the planet well beyond their own lifetimes. Finance people are not the only ones who invest in the future and act to benefit their heirs.

People vary a great deal in the extent to which they care about the future. When the benefits of an action in the present are highly diluted and spread among many people in the future, the motivation to act is likely to be much weaker than it would be when action is taken to benefit those who are very close in term of geographical, temporal, and social distance.[66]

Many people look far into the future and serve it. They also go beyond time to their spiritual worlds, in forms of transcendent caring. The pyramids of Egypt and the world’s great cathedrals, synagogues, temples, and mosques were envisioned by architectural masters who knew they would never see the fruits of their work. Notre Dame in Paris, St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Il Duomo in Milan, and Sagrada Familia in Barcelona are good examples. They demonstrate transcendent caring, beyond time.

Gaia thinking focuses on the earth as a source of care for people. Consider the more cosmic caring embodied in the much-quoted passage from Hafiz, a 14th century Sufi poet:

After a million years of shining

The sun never says to the earth –

‘You owe me.”

Imagine a love like this,

it lights up the Whole Sky

Whether viewed as fact or metaphor, the message is clear: Provide sunshine for others, without expecting anything in return.

Evolutionary Biology

The differences between animals and inanimate nature like plants and mountains seem obvious. Animals are sentient beings, but the others are not—we think. But microbiologists and deep sea explorers tell us that there are some life forms that seem to straddle that boundary. And the close dependence between animals and inanimate nature become apparent when we reflect on the observation, “all flesh is grass”.

We sometimes attribute life-like characteristics to groups of animals. Herds and flocks and nations often seem to take on a life of their own, with a kind of group consciousness that is somehow above and beyond that of the individual members. There is something very real about groups, even though the connections among their members are not visible. They have something of a transcendent, spiritual nature.

We often distinguish between humans and animals, but of course humans can be viewed simply as another type of animal. All show caring behavior. Humans have certain distinctive characteristics, but so does every other species. All have distinct roles in the global ecosystem. Only one thinks of itself as the primary one.

Evolutionary biologists help us overcome our self-indulgent preoccupation with our own species, encouraging us to see that we are parts of a much larger whole. All the elements that make up that whole depend on each other and, in various ways, care for each other.

However, there are many unanswered questions. According to Jonathan Sacks, Charles Darwin “was puzzled by a phenomenon that seemed to contradict his most basic thesis, that natural selection should favor the ruthless”:

Altruists, who risk their lives for others, should therefore usually die before passing on their genes to the next generation. Yet all societies value altruism, and something similar can be found among social animals, from chimpanzees to dolphins to leafcutter ants.

Neuroscientists have shown how this works. We have mirror neurons that lead us to feel pain when we see others suffering. We are hard-wired for empathy. We are moral animals.[67]

Sacks summarizes a core finding of evolutionary biology: “we survive as members of groups, and groups can exist only when individuals act not solely for their own advantage but for the sake of the group as a whole.”

The idea that we are purely, narrowly, and exclusively self-interested is wrong. We are not ruthless and lonely savages. We are self-interested, but we are also concerned with the well-being of others.

There is a problem, however. Some people suggest that concern for the group as a whole is about universal concern for others. The reality is that we tend to be deeply concerned only about selected others. We are not “all one,” but members of many different groups. We are tribal by nature.

There are many different bases for tribal divisions, including culture, ethnicity, and religion. Many tribes are in conflict with others, and often these conflicts turn violent. Often the caring for one’s own group is tightly linked to hostility to others. People working within a corporation may feel strong solidarity as they struggle to overcome their competitors. Soldiers in the front lines put themselves in harm’s way not to protect their individual selves, but to protect their brothers in arms and their tribes back home. Killing is often claimed to be for a noble, selfless cause. Conflict with some can be driven by caring for others.

Strengthened bonds of caring within tribes can lead to aggressiveness and sharp conflicts between tribes. No one has yet found a good way to control that, especially in the anarchic world of international relations, where nationalism has been a potent force for both good and evil.

Some people suggest that major conflicts are due to tribal differences such as religious differences. But differences do not necessarily lead to conflict. Diverse tribes can happily co-exist so long as they don’t invade each other’s space, just as many different plants and animals can find a sensible equilibrium, living together harmoniously in their ecological space. Serious conflicts arise only when one tribe tries to impose its will on others.

Sustained conflicts between tribes often lead to the fracturing of bonds within the tribes, turning what might have been a simple manageable inter-tribal conflict into an intractable one. In the Middle East, for example, negotiations have become extremely difficult not only because of the incompatible positions of the Israelis and the Palestinians, but also because the divisions within each of those groups make constructive negotiations impossible. Jonathan Sacks thinks religion “remains the most powerful community builder the world has known,”[68] but he does not discuss the long history of intense conflict between religious groups, or the fact that every major religion is divided within itself and has distinct progressive and fundamentalist branches. The Crusades continue on, even if many in the New World don’t understand that.

Some evolutionary biologists see cooperation as a way in which some tribes can win in a deeply competitive world. Thus, Martin Nowak distinguishes five mechanisms of cooperation that can serve as strategies for winning in various types of struggle.[69],[70]

The evolutionary biology approach may appear to explain some types of positive behavior in some circumstances, but how would it explain indifference or negative behavior? Why would a young man kill 20 school children in Newtown, Connecticut? Why would anyone set fire to a home in Webster, New York so that he could kill the fire fighters who try to protect the home and the people in it?[71] Why would people deliberately steer their cars to kill turtles crossing the road?[72] Why is there such widespread neglect and abuse of women, children, the elderly, animals, and nature? Attributing such actions to mental health problems does not explain them. Are these the behaviors of losers in a Darwinian struggle for survival?

Some evolutionary biologists look for explanations for caring behavior in some kind of indirect payoff, such as gaining advantages for one’s tribe or gene pool over others. However, as pointed out earlier, caring people like Mother Teresa and Saint Damien were not concerned with gaining advantages over others. The goal of people’s living well together with dignity and with respect for each other and their environment seems enough to explain why most people treat each other well most of the time.

Nowak’s five mechanisms do not explain nice behavior in a non-competitive world. Evolutionary biologists who examine the benefits of cooperation in the context of struggles of various forms implicitly assume there must be losers. Must there be losers?

What Sacks viewed as an unsolved puzzle faced by Darwin actually was addressed by Darwin late in life. His masterwork, The Origin of Species, focused on pre-human evolution. However, in Darwin’s much ignored later book, The Descent of Man, he concluded that in human evolution, morality and conscience were more important than the idea of survival of the fittest.[73] ,[74], [75], [76] As one observer summarized:

Darwin specifically denies that “the foundation of the most noble part of our nature” lies “in the base principle of selfishness.” This flies in the face of the prevailing evolution paradigm, however, a form of neo-Darwinism in which sociobiologists are vigorously pushing the idea that even altruism must be understood as motivated strictly by selfishness.[77]

Some environmental biologists’ analyses begin with Darwin and the need to survive. But then their discussion is somehow transformed into one about winning—whatever that might mean. Casting the struggle as being about winning means one assumes a world of perpetual conflict, one in which there must be losers. However, any stable ecology demonstrates the possibilities for long-term peaceful coexistence among individuals and groups of many different kinds. We do not have to live in a world of winners and losers.

Why do we often emphasize competition rather than cooperation? A friend told me that when he went to school, children were used to studying together. So when it was classroom exam time, if they didn’t know the answer to a question, they would ask the child sitting in the next row. Then they would be scolded by the teacher, and were told that learning from another child was cheating.

What’s wrong with asking your neighbor when you are facing a puzzle? In a school based on deep caring, “Tests would be taken by groups helping one another get to correct answers, rather than separating children and ranking one higher or smarter than the other after the tests.”[78]

Why is it that environmental biologists have become so preoccupied with the idea of winning? The Social Transformation Faculty of Saybrook University asked, why is it that we “glorify winning as the undoing of an enemy, rather than an opportunity for life-saving reconciliation?” They articulated another option:

We support the development of a culture of transformative personal, organizational, and social change that fosters and celebrates the highest human qualities and practices, including empathy, altruism, peaceful conflict resolution, and restorative justice.[79]

It is possible to organize things so everyone survives, but there is no way to organize so that everyone wins over others. It is possible for everyone to live well. We sometimes face a savage, competitive world, but not always, and not necessarily. There is enough for everyone’s needs; but not for everyone’s greed.

In The Conquest of Bread, Peter Kropotkin made the point clearly: “Well-Being for all is not a dream. It is possible, realizable, owing to all that our ancestors have done to increase our powers of production.”[80] He spoke about our technological possibilities. Whether we actually seek well-being for all is another question. To illustrate, collectively, we certainly have the capacity to end hunger in the world. Whether we have the motivation to actually do that is a different issue. There are no technological obstacles.[81]

Why assume there must always be competitors or that it is important to have one’s own tribe outdo others? The idea of living well together might be enough to explain and motivate caring behavior.

Increasing the Caring

The intensity of caring by individuals and groups can be estimated by using various indicators such as crime, charitable giving, and volunteerism. Obviously, individuals and groups vary a great deal on this dimension. The question raised in this section is: what could be done to go beyond simply describing the phenomenon of caring, to instead increase the caring? It is not obvious. Preaching at people to treat one another nicely might help a bit. Having parents and teachers and other role models act nicely certainly has a positive influence. What else could be done to increase the caring in significant ways?

One promising approach has been developed in a private school in Hawai’i. Since 1991, its Psychosocial Education Department has operated alongside the more conventional math, English, history and science departments with the specific purpose of building empathy skills.[82] Using a broad variety of group activities such as ropes courses, along with more conventional classroom teaching, it appears to be successful.

There is a Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University:

CCARE investigates methods for cultivating compassion and promoting altruism within individuals and society through rigorous research, scientific collaborations, and academic conferences. In addition, CCARE provides a compassion cultivation program and teacher training as well as educational public events and programs.[83]

Harvard University has a project called “Making Caring Common” that “helps educators, parents, and communities raise children who are caring, respectful, and responsible toward others and their communities.”[84]

An approach to learning empathy is suggested in a YouTube video and a magazine article that advocates “outrospection,” in contrast to introspection, and suggests the creation of a museum of empathy that would help visitors come to a deeper understanding of other people’s lives.[85] [86]

Drawing from the work of the late psychiatrist M. Scott Peck, the Foundation for Community Encouragement offers workshops designed to build the sense of community.[87]

Apparently there is one major key to increasing the caring: Relationships are strengthened when people work and play together. This is an important element that should be designed into new communities and strengthened in existing communities. Local orchestras, sports teams, community projects, and business cooperatives, for example, all tend to strengthen bonds among their members. In well-designed communities, where people work and play together in many ways, people are likely to care for each other and for the local environment in which they are embedded.

Figure 5. Relationships are strengthened when people work and play together. Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/df/Our_Community_Place_Sandbox.jpg

Bonding among people who work and play together can take place in the pursuit of virtuous ends, such as producing good music, or questionable ones, such as those pursued by the Ku Klux Klan or street gangs.

One traditional form of group activity around a single goal is barn-raising, well known especially in Amish communities. There is a modernized version based on the WikiHouse, built with an open-source construction set, where “people always want to join in and lend a hand”.[88]

At the outset, the goals might be based on narrow self-interest. You might help a neighbor build his barn based on the anticipation that at some later time he might help you with a project of your own. However, over time, the practice of doing things based on instrumental caring might evolve into increasingly empathetic caring. After a time, you might come to like your neighbor and want to do things for him, even things for which there are no likely “returns on the investment.”

In many cases, people band together to challenge a common enemy, whether a colonizer, an invading army, or a virus. Often that cooperation is based on each individual pursuing his or her individual interests. But over time, the collegiality involved in the effort is likely to transform the relationships into forms that go beyond simply using others, to showing some affection for them. We see this in the solidarity among soldiers or football players.

Being together and doing things together is likely to increase the caring. The thought is alarmingly simple. Apparently it is true for many different types of caring. As Kenneth Worthy explains,

Only by being in sensuous, embodied contact with the rich, vibrant, complex realm of nature in landscapes and seascapes, with the air, soil, and water around us, can we begin to fully understand and experience nature’s needs and thus be in a reciprocal and caring relationship with it.[89]

New communities can be designed or existing ones can be modified with a view to building the caring. Community design efforts often focus on the physical arrangements, but attention can also be given to the ways in which well-arranged communities can strengthen social relationships.

We can define strong communities as those in which people care about one another’s well-being. They might be comprised of people who live close to one another and interact regularly. Employment opportunities, housing, and other amenities could be located in a defined contiguous space, thus allowing many of the residents to work close to where they live. Each community could have a management body, and rules determined through highly participatory processes. Such communities could produce much of their own food, and manage energy, waste disposal and many other concerns at the community level. Such communities would strive for sustainability, resilience, and self-reliance.

In such communities, people are likely to care for each other and for the local environment in which they are embedded. But there are no guarantees. The character of the community that emerges from the planning process would depend on the views and values of the individuals who do the planning. If the planning group advocates good nutrition, healthy people, healthy environments, and caring, the plans it puts out would reflect that input. Once implemented, this sort of community is likely to strengthen and transmit those values.

There has been a great deal of discussion of how businesses might pursue the “triple bottom line,” giving attention not only to profits, but also to people and the planet.[90] These “three Ps” could be pursued not only in the design of businesses but also in the design of strong communities. If a group of like-minded people brought in all their best ideas, drawing on everything they could learn about the best and the worst of both pre-modern and modern worlds, and had few obstacles in already-existing arrangements, they would have the potential for doing wonderful things together.

Tracing the motivation to benefit others shows us a common thread through all types of caring, ranging from the obvious forms that occur between parents and children to the more transcendent forms of caring for people and things beyond direct observation. Caring provides the basis for genuine connectedness, through many dimensions.

Empathetic caring takes connectedness beyond the merely mechanical and instrumental to something that is more deeply satisfying for us, individually and collectively. We need to work at understanding and increasing caring.

NOTES:

[1] Peter Kropotkin, (1902). Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Anarchy Archives. dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/kropotkin/mutaidcontents.html

[2] Adam M. Grant (2013) “Does Studying Economics Breed Greed?” Huffington Post: The Blog. October 22. www.huffingtonpost.com/adam-grant/does-studying-economics-b_b_4141384.html

[3] Doug Contri (2011). “Empathy and Barriers to Altruism.” Peace and Conflict Review, Vol. 6, Issue 1. Fall. www.review.upeace.org/images/pcr6.1.pdf

[4] Adam M. Grant, (2013). Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success. New York: Viking/Penguin

[5] Fairfax NZ News (2012). “Free school milk in classrooms.” Stuff.co.nz. www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/8076081/Free-school-milk-back-in-classrooms

[6] 3 News (2012). “Fonterra hopes milk campaign will drive demand.” 3 News. December 14 www.3news.co.nz/Fonterra-hopes-milk-campaign-will-drive-demand/tabid/421/articleID/280345/Default.aspx#ixzz2EyezfXwk

[7] George Kent (2011). Regulating Infant Formula. Amarillo Texas: Hale Publishing. George Kent (2015). “Global infant formula: monitoring and regulating the impacts to protect human health.” International Breastfeeding Journal, Vol. 10, No 6. DOI: 10.1186/s13006-014-0020-7 http://www.internationalbreastfeedingjournal.com/content/10/1/6/abstract

[8] Michele Simon (2012). “Feds to Parents: Big Food Still Exploiting Your Children; Good Luck With That.” Food Safety News, January 8. www.foodsafetynews.com/2013/01/feds-to-parents-big-food-still-exploiting-your-children-good-luck-with-that/#.UO59q7bahgI

[9] Patrick Mustain, (2013). “Dear American Consumers: Please Don’t Start Eating Healthfully. Sincerely, the Food Industry.” Scientific American. May 19. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2013/05/19/dear-american-consumers-please-dont-start-eating-healthfully-sincerely-the-food-industry/

[10] J.Macaulay and L. Berkowitz (1970). Altruism and Helping Behavior. New York: Academic Press.

[11] Jennifer L Goetz.; Dacher Keltner; and Emiliana Simon-Thomas. “Compassion: An Evolutionary Analysis and Empirical Review.” Psychological Bulletin. Vol. 136, No. 3 pp. 351-374. greatergood.berkeley.edu/resources/studies#compassion_evolutionary_analysis_empirical_review

[12] Robert M Axelrod (2006)The Evolution of Cooperation. Revised Edition. New York: Basic Books.

[13] Carl Ratner (2012). Cooperation, Community, and Co-Ops in a Global Era. Springer.

[14] Merriam-Webster (2012). “Schadenfreude” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/schadenfreude

[15] Adam M. Grant (2013). Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success. New York: Viking/Penguin.

[16] Maria Popova, (2013). “Givers, Takers, and Matchers: The Surprising Science of Success.” Brain Pickings. www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/04/10/adam-grant-give-and-take/

[17] Emily Brennan (2012). “Trying to Close Orphanages Where Many Aren’t Orphans at All.” New York Times. December 4. www.nytimes.com/2012/12/05/world/americas/campaign-in-haiti-to-close-orphanages.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20121205&_r=0

[18] Credit Suisse (2013). Global Wealth 2013: The Year in Review. Credit Suisse Research Institute. https://publications.credit-suisse.com/tasks/render/file/?fileID=BCDB1364-A105-0560-1332EC9100FF5C83

[19] Sang-Hun, Choe (2013). “As Families Change, Korea’s Elderly Are Turning to Suicide.” New York Times. February 16. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/17/world/asia/in-korea-changes-in-society-and-family-dynamics-drive-rise-in-elderly-suicides.html?ref=choesanghun&_r=0

[20] Peter Edelman (2012). So Rich, So Poor: Why it’s So Hard to End Poverty in America. New York: The New Press.

[21] Max Fisher (2012). “Study: Global crop production shows some signs of stagnating.” Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2012/12/24/is-production-of-key-global-crops-stagnating/

[22] nef (2013). National Accounts of Well-Being. Website. www.nationalaccountsofwellbeing.org/

[23] Malavika Vyawahare (2013). “India’s Battle Against Nutrition Data Deficiency.” International New York Times. October 24. india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/24/indias-battle-against-nutrition-data deficiency/?emc=edit_tnt_20131024&tntemail0=y

[24] Marc Pilisuk and Susan Hillier Parks (1986). The Healing Web: Social Networks and Human Survival. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

[25] Ubuntu Age (2012) We have entered The AGE of UBUNTU. www.harisingh.com/UbuntuAge.htm

[26] Joburg (2013) /Caring Cities 2013. Website. http://joburg2013.metropolis.org/

[27] Karl Polanyi (1944). The great transformation. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, p. 172. uncharted.org/frownland/books/Polanyi/POLANYI%20KARL%20%20The%20Great%20Transformation%20-%20v.1.0.html

[28] George Kent (2011). Ending Hunger Worldwide. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers.

[30] George Kent (2011). Ending Hunger Worldwide. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. p. 136

[31] West-Eastern Divan Orchestra 2015. Website. www.west-eastern-divan.org

[32] Sara Jawhari (2012). Polyphony Youth Orchestra Unites Palestinian and Jewish Israelis. Arab American Institute. June 21. www.aaiusa.org/blog/entry/polyphony-youth-orchestra/

[33] George Kent (2011). Ending Hunger Worldwide. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers.

[34] Jeffrey Crawford (2012). 7 True Stories of Animals Rescuing People from Certain Death. Cracked.com November 4. www.cracked.com/article_20054_7-true-stories-animals-rescuing-people-from-certain-death.html

[35] Jamie Frater (2010). Top 10 Cases of Animals Saving Humans. Listverse. listverse.com/2010/03/14/top-10-cases-of-animals-saving-humans/

[36] Today Pets & Animals (2010). Pet saviors: 11 animals who saved human lives. NBCNews.com April 28. today.msnbc.msn.com/id/36834168/ns/today-today_pets_and_animals/t/pet-saviors-animals-who-saved-human-lives/#.UO55VqWIM7Q

[37] Frans de Waal (2009). The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. New York: Harmony

[38] Maneka Gandhi, (2013). “Animals too are emphathetic.” Mathrubhumni. March 19. www.mathrubhumi.com/english/story.php?id=134370

[39] Kate Wong, (2012). “Lending a Helping Paw: When Animals Cooperate.” Slide Show. Scientific American, June 19. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=cooperation-when-animals-cooperate-lending-helping-paw&WT.mc_id=SA_printmag_2012-07

[40] ABC TV (2013). “Lions, Tiger and Bears living Together.” ABC News. abcnews.go.com/WNT/video/lions-tigers-bears-living-18928105

[41] Barbara King (2013). How Animals Grieve. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[42] Jeffrey Kluger (2013). “The Mystery of Animal Grief.” Time. April 15, p. 45. http://time.com/597/the-mystery-of-animal-grief/

[43] Daryndama (2007). Cat and Bird. YouTube Video. April 28. www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0nuNuFbanA

[44] Chibudgiuelvr (2009). Rat loves cat! YouTube Video. www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ikm3o5hDks

[45] Chibudgielvr (2009). Rat loves cat! – Rejection (Part 2). YouTube Video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-h2YxyncyU

[46] Public Broadcasting System 2013. What Plants Talk About. Nature. www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/episodes/what-plants-talk-about/video-full-episode/8243/

[47] Michael Pollan, (2013). “The Intelligent Plant.” The New Yorker. December 26 and 30, pp. 92-105. www.newyorker.com/reporting/2013/12/23/131223fa_fact_pollan?currentPage=all

[48] phys.org (2013). “Can plants be altruistic? You bet, study says.” phys.org, February 1. www.phys.org/news/2013-02-altruistic.html

[49] Elisabet Sahtouris, (1998). The Biology of Globalization. www.ratical.org/LifeWeb/Articles/globalize.html

[50] Elisabet Sahtouris (1998). The Biology of Globalization. www.ratical.org/LifeWeb/Articles/globalize.html

[51] Tjeerd Deelstra, (1987). ” Urban agriculture and the metabolism of cities.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 9(2): 5-7. www.unu.edu/unupress/food/8f092e/8F092E03.htm.

[52] Nonhuman Rights Project. Website. www.nonhumanrightsproject

[53] Christopher D Stone (1974). Should Trees Have Standing: Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann.

[54] Christopher D Stone (1987). Earth and Other Ethics: The Case for Moral Pluralism. New York: Harper & Row.

[55] Brendan Kennedy (2012). “I Am the River and the River is Me: The Implications of a River Receiving Personhood Status.” Cultural Survival Quarterly. November 26. http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/i-am-river-and-river-me-implications-river-receiving

[56]Michael Barnett (2012). The Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

[57] George Kent (2014). “Rights and Obligations in International Assistance.” In Peter Bobrowsky, ed., Encyclopedia of Natural Hazards. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. Republished in Disaster Management and Prevention, 2014, Vol. 23, No. 3. www2.hawaii.edu/~kent/DPMRightsandObligationsinIHA.pdf

[58] Deborah Kelemen; Joshua Rottman; and Rebecca Seston (2012). “Professional Physical Scientists Display Tenacious Teleological Tendencies: Purpose-Based Reasoning as a Cognitive Default.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. October 15. www.bu.edu/childcognition/publications/2012_KelemenRottmanSeston.pdf and

[59] Deborah Kelemen (2012). “Teleological minds: How natural intuitions about agency and purpose influence learning about evolution.” In K. S. Rosengren, S. K. Brem, E. M. Evans and G. M. Sinatra (eds.), Evolution challenges: Integrating research and practice in teaching and learning about evolution. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. www.bu.edu/childcognition/publications/2012_Kelemen.pdf

[60] Alan Lightman (2014). “Our Lonely Home in Nature.” New York Times. May 2. www.nytimes.com/2014/05/03/opinion/our-lonely-homeinnature.html?emc=edit_th_20140503&nl=todaysheadlines&nlid=2155033&_r=0

[61] Daniel Zeleznik (2013). UN General Assembly Commemorates International Mother Earth Day with Harmony with Nature Dialogue. Boston, Massachusetts: Global Environmental Governance Project. May 13. www.environmentalgovernance.org/event/2013/05/un-general-assembly-commemorates-international-mother-earth-day-with-harmony-with-nature-dialogue/

[62] www.harmonywithnatureun.org/index.html

[63] Laura Westra (2006). Environmental Justice and the Rights of Unborn and Future Generations: Law, Environmental Harm and the Right to Health. London: Earthscan.

[64] Karma Kitchen (2013). Website. www.karmakitchen.org/

[65] Pavithra Mehta (2013). “Lessons from a Pay-It-Forward Restaurant: The Importance of Gratitude.” Yes! November 1. www.yesmagazine.org/happiness/a-yes-invitation-join-us-in-a-21-day-challenge-to-express-gratitude-everyday?utm_source=YTW&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=20131101

[66] Bryan Walsh (2013). “Why We Don’t Care About Saving Our Grandchildren From Climate Change.” Time. October 21. science.time.com/2013/10/21/why-we-dont-care-about-saving-our-grandchildren-from-climate-change/?xid=newsletter-weekly

[67] Jonathan Sacks (2012). “The Moral Animal.” New York Times. December 23. www.nytimes.com/2012/12/24/opinion/the-moral-animal.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20121224

[68] Jonathan Sacks (2012). “The Moral Animal.” New York Times. December 23. www.nytimes.com/2012/12/24/opinion/the-moral-animal.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20121224

[69] Martin A. Nowak and Roger Highfield (2012). Super Cooperators: Altruism, Evolution, and Why We Need Each Other to Succeed. Free Press.

[70] Martin A. Nowak “Why We Help.” Scientific American. July (2012), pp. 34.

[71] Liz Robbins and N. R. Kleinfield (2012). “4 Firefighters Shot, 2 Fatally, in New York; Gunman Dead.” New York Times. December 24. www.nytimes.com/2012/12/25/nyregion/2-firefighters-killed-in-western-new-york.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[72] Jeffrey Collins (2012). “College Student’s Turtle Project Takes Dark Twist.” ABC News. December 27. abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/college-students-turtle-project-takes-dark-twist-18076298#.UN4JqLbahgI

[73] David Loye (200). Darwin’s Lost Theory: Bridge to a Better World. Third Edition. Benjamin Franklin Press.

[74] David Loye (2013). Website. www.davidloye.com/

[75] Eric Michael Johnson (2013). “Survival of the . . .Nicest? Check Out the Other Theory of Evolution.” Yes! Magazine. May 3. www.yesmagazine.org/issues/how-cooperatives-are-driving-the-new-economy/survival-of-the-nicest-the-other-theory-of evolution?utm_source=ytw20130503&utm_medium=email

[76] Colin Tudge (2013). Why Genes Are Not Selfish and People Are Nice. Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris, Books.

[77] Jane Lampman (2000). “Moral Darwinism: The Fittest Conscience: A New Take on Evolution.” Christian Science Monitor. August 3. http://www.101bananas.com/library2/lampman.html

[78] Poka Laenui (2013). “From the Culture of Aloha, a Path Out of Gun Violence.” Yes! February 7. www.yesmagazine.org/issues/how-cooperatives-are-driving-the-new-economy/violence-guns-and-deep-cultures?utm_source=wkly20130208&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=mrLaenui

[79] As cited in Mark Schulman, (2012). “How to Combat a Culture of Violence—and Maybe Save Lives.” Huffington Post: The Blog. December 27. www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-schulman/combat-culture-of violence_b_2371661.html

[80] Peter Kropotkin (1906). The Conquest of Bread. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/kropotkin/conquest/toc.html

[81] George Kent (2011). Ending Hunger Worldwide. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers.

[82] Lavonne Leong (2012). “Peer-to-Peer Potential: Building a Culture of Empathy at Punahou.” Punahou Bulletin. Winter. www.punahou.edu/page.cfm?p=3865

[83] CCare (2013). Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education. Website. ccare.stanford.edu/about/mission-vision/

[84] Making Caring Common Project. Website. sites.gse.harvard.edu/making-caring-common

[85] Roman Krznaric (2012). “The Power of Introspection.” Video. RSA Animate. www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=BG46IwVfSu8

[86] Roman Krznaric (2013). “6 Habits of Highly Empathetic People.” Yes Magazine. January 10. www.yesmagazine.org/happiness/6-habits-of-highly-empathetic-people?utm_source=wkly20130111&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=mrKrznaric

[87] FCE (Foundation for Community Encouragement) (2013). Website at fce-community.org/

[88] Alastair Parvin, and Evan O’Neil (2012). “Open Source WikiHouse Disrupts Traditional Design.” Carnegie Council: Policy Innovations. www.policyinnovations.org/ideas/innovations/data/000216?sourceDoc=00072

[89] Kenneth Worthy (2013). Invisible Nature: Healing the Destructive Divide between People and the Environment. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

[90] The Economist (2009). “Triple Bottom Line: It Consists of Three Ps: Profit, People and Planet.” The Economist. November 17. www.economist.com/node/14301663

_______________________________________________

TRANSCEND member George Kent is Professor Emeritus with the University of Hawai’i, having retired from its Department of Political Science in 2010. He teaches an online course on the Human Right to Adequate Food as a part-time faculty member with the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney in Australia and also with the Transformative Social Change Specialization at Saybrook University in California. His recen books on food policy issues are Freedom from Want: The Human Right to Adequate Food, Global Obligations for the Right to Food, Ending Hunger Worldwide, and Regulating Infant Formula. He can be reached at kent@hawaii.edu.

TRANSCEND member George Kent is Professor Emeritus with the University of Hawai’i, having retired from its Department of Political Science in 2010. He teaches an online course on the Human Right to Adequate Food as a part-time faculty member with the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney in Australia and also with the Transformative Social Change Specialization at Saybrook University in California. His recen books on food policy issues are Freedom from Want: The Human Right to Adequate Food, Global Obligations for the Right to Food, Ending Hunger Worldwide, and Regulating Infant Formula. He can be reached at kent@hawaii.edu.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 29 May 2017.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: On Caring, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4 Responses to “On Caring”

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

This is a wonderful and most important article. I hope it will be widely read and practised. Thank you so much

What a wonderful article! Kudos to the author and to Transcend for carrying it.

Reading and understanding this will teach you why “caring” is the foundation for peace. Not “a” foundation but _the_ foundation.

Let me join Lorena and Pablo – this is a manificent article and it deserves to be shared and shared!

I want to thank all who have commented, and will comment, at https://www.transcend.org/tms/2017/05/on-caring/#comments on my essay, “On Caring”

My article was shared on the Transcend Media Service on May 29, 2017, based on its original publication in Michelle Brenner, ed., Conversations on Compassion. Sydney, Australia: Holistic Practices Beyond Borders, 2015. http://www2.hawaii.edu/~kent/OnCaring.pdf I appreciate all the kind words about the article.

Going forward, we need to give more systematic attention to the importance of caring in dealing with many other issues. I explored caring in relation to one theme in a recent book Caring About Hunger (http://www.lulu.com/shop/george-kent/caring-about-hunger/paperback/product-22919316.html) Comparable studies could be done to show the importance of caring in relation to many other issues, especially those of interest to people in peace studies.