Peace Journalism – A Global Debate

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 19 Jun 2017

Meah Mostafiz – TRANSCEND Media Service

“If the critics of peace journalism were in Rwanda in 1994 or Kenya in 2008 or Uganda in 2009, what would they have said to the purveyors of hate radio?”

— Steven Youngblood

- Abstract

Whether the Rwandan hate radio that motivated people to take part in mass killings or today’s global media that fuels tension between USA and Russia, news reporting has traditionally been feeding on war, conflict and violence, often offering propaganda for one of the conflicting parties, and without any apparent intention to promote peace. For the war and conflict or ethnic violence scene, peace journalism brings reporting method that finds causes of conflict and tries to suggest solutions, instead of pouring more fuel on the fire. This research paper defines the peace journalism, the difference between traditional journalism and peace journalism and analyses the factors why Peace Journalism is hard to practice in mainstream media?

- Introduction

In Rwanda, Indonesia or in former Yugoslavia, societies have experienced the havoc of violent conflict, and there media played a blatant role in fueling the destructive fires of enmity. (Hackett 2006) Access to information is a fundamental human right. Nationally or internationally people often depend on Media for getting information. Media plays the central role in international affairs, dispute and violence. Scholars consider information failure as a primary contributor to growing fear that increases the possibility of violent conflict. On the other hand the significant role of communication flow in conflict resolution frequently focus on nation-states and highlights the role of media in the construction and reinforcement of simplistic and extremely negative images of the “other”. Thus national media exhibit a strong tendency to cover terrorism, war, and international relations from an ethnocentric position in which news “bears a remarkable resemblance to many sentiments common in the government’s foreign policy and, indeed, the nation’s political culture” (Steuter 1990)

Journalists control our access to news, by pitching stories from particular angles. Media set the agenda for public debate. In Reporting Conflict, Jake Lynch and Johan Galtung challenge reporters to tell the real story of conflicts around the world. The dominant kind of conflict reporting is what Lynch and Galtung call war journalism: conflicts are seen as good versus evil, and the score is kept with body counts. The media’s handling of 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq highlight the one-sided reporting that war journalism creates. Peace journalism uses a wider lens: why not report what caused the conflict, and how it might be resolved? Lynch and Galtung show how journalists could have taken a broader approach to reporting conflicts like the Korean War and the NATO bombing of Kosovo to spark a more constructive public debate. (Lynch and Galtung 2010)

Media as a third party to any conflict; the third party is the facilitator of communication, the mediator or the arbitrator between the two rival sides. It is our contention that Peace Journalism as a third side can best enhance prospects for resolution and reconciliation by changing the norms and habits of reporting conflicts. (Peleg 2006)

Peace Journalism is a bold attempt to redefine and reconstruct the role of journalists who cover conflicts. As a new arena of knowledge, Peace Journalism draws upon several theories and disciplines to enrich its validity and applicability. A major source which peace journalism can rely on to bolster it’s analytical as well as its normative rigor is conflict theory. Peace journalism renders a powerful tool in the hands of reporters and their readers to realize the futility of conflict and to bring about its resolution. However, Peace Journalism is not been practiced in mainstream media, and we will discuss, why.

In this paper we are going to discuss what peace journalism is, difference between traditional journalism and Peace journalism, and the factors behind why peace journalism is not being practiced in mainstream media.

- Part One

3.1 Definition of Peace Journalism and the role of a Peace Journalist

Peace Journalism is defined likewise “when editors and reporters make choices – of what to report, and how to report – that create opportunities for society at large to consider and value non-violent responses to conflict” (Lynch and McGoldrick, 2005) Peace journalism shows backgrounds and contexts of conflicts; hears from all sides; explores hidden agendas; highlights peace ideas and initiatives from anywhere at any time. (Lynch 2005)

According to Reporting the world (2013), Peace Journalism advocates change in journalism, but it is not trying to turn journalism into something else. Research shows that reports of violence and devastation are prevailing, in most reporting of conflict, most of the time. Therefore there is need to give peace a chance – and that’s peace journalism.

According to The Center for Global Peace Journalism at Park University Peace Journalism (2013) is when editors and reporters make choice that improves the prospects for peace. These choices, including how to frame stories and carefully choosing which words are used, create an atmosphere conducive to peace and supportive of peace initiatives and peacemakers, without compromising the basic principles of good journalism. Peace Journalism gives peacemakers a voice while making peace initiatives and non-violent solutions more visible and viable.

The example Lynch refers to is the details of deaths and destruction wrought by a bomb. There are casualty figures, from trustworthy sources such as hospitals and the police. What is automatically more controversial is to probe why the bombers did it, what was the course of action that led to bombing, what were their claim and motivation.

Lynch (2005) defines that peace journalism is quality journalism that uses a creative set of tools to include routinely or habitually under-represented perspectives to provide deeper and broader coverage of news. It foresee or portrays a conflict-free society, helps produce a society “good at handling conflict non-violently”. Kempf (2002) on the other hand rejected attempts to understand peace journalism as a form of advocacy and favors peace journalism as “good journalism” that goes well beyond simplistic dualism of good and bad. He suggested a two-stage strategy to reduce the escalation orientation of mainstream conflict coverage. His first stage of “de-escalation oriented coverage” is characterized by neutrality and critical distance from all parties to the conflict and coincides broadly with what is generally considered quality journalism. It goes beyond the professional norms of journalism only to the extent that the journalists’ competence in conflict theory produces coverage in which the conflict is kept open to a peaceful settlement. His second stage requires the abandonment of dualism and the re-framing of conflict as a cooperative process through “solution-oriented coverage,” which, he concluded, is likely to garner majority support only when an armistice or a peace treaty is already in place.

Lynch thinks the reason why there is too little option to news about peace initiatives, if no underlying causes are visible, there is nothing to fix only in this form of reporting does make sense to view ‘terrorism’ as cause of war. And if a journalist wait, to report on either underlying causes or peace initiatives, until it suits political leaders to discuss or engage with them, it might take a long time. Peace journalism, as a remedial strategy and an attempt to supplement the traditional news principles to give peace a chance. Thus Peace journalism: Investigate the backgrounds and contexts of conflict formation, presenting causes and options on every side;

- Gives voice to the views of all rival parties, from all levels;

- Offers inventive ideas for conflict resolution, development, peacemaking and peacekeeping;

- Gives consideration to peace stories and post-war developments.

3.2 Brief history of Peace Journalism

Peace Journalism Model can be found in Galtung and Ruge’s article entitled “The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers” published in 1965 on the Journal of Peace Research. Galtung and Ruge provided a key conceptual groundwork in 1965 and in later studies. However Peace Journalism flourished significantly in the South Pacific in the 1990s, notably the Philippines. Although often Peace Journalism called ‘conflict-sensitive journalism’, which recently become an approach seriously considered as applicable in a South Pacific context, especially in the wake of the Bougainville civil war and the Solomon Islands ethnic conflict. With other political upheavals in Fiji in two decades, paramilitary revolts in Vanuatu, riots in Tahiti and Tonga, protracted conflict in Papua New Guinea’s Highlands, and the pro-independence insurrection in New Caledonia in the 1980s, conflict resolution poses challenges for the region’s journalists and their education and training. (Robie 2011)

Peace journalism has emerged, since the mid-1990s, as a new trans-disciplinary field, of interest to professional journalists, in both developed and developing countries, and to civil society activists, university researchers and others interested in the conflict-media nexus, all derived from, or at least attentive to, propositions about conflict, violence and peace from Peace and Conflict Studies.(Lynch 2005)

Peace Journalism has been embraced, under that name, by journalists in mainstream media in Indonesia, and some in the Philippines, following grassroots campaigns and journalist training interventions by Jake Lynch and Annabel McGoldrick, more so it is being practiced by many journalists, in many different places around the world, all the time. (Lynch 2005)

At the beginning of 21st century, Galtung, Kempf , Shinar and others advocated creative models and training programs to transform the role of media. Young and Jesser in 1997 proposed that international media consolidate and concentrate their coverage to establish a single press consortium with the economic and tactical independence of governments to provide a truly autonomous alternative voice. (Ross 2006) Both contended that media could play a critical positive role in conflict prevention. Gorsevski suggested that the media could advance “propaganda of peacemaking” by re-humanizing individuals engaged in conflict through a non-violent rhetoric (Chilton 1987).

Fabris and Varis in 1986, Hackett in 1991 have asserted that more systematic scientific analysis and empirical data on media coverage of war and peace are vital to understand the roles of the media and to mitigate social harms of media coverage. Daugherty and Warden in 1979 argued that far-flung attacks on U.S. media coverage of the Middle East had been made “without substantial empirical data” about their content or their effects; their analysis of 11 years of editorials in four elite newspapers found the press provided overwhelmingly more favorable coverage of Israel than Palestine but the skew in coverage was event driven, and press support for Israel was “neither monolithic nor invariable.”(Ross 2006)

Peace Journalism is now a globally distributed reform movement of reporters, academics and activists from Africa to the Antipodes. Academic courses are now being taught in the UK, Australia, USA, Mexico, South Africa, Costa Rica, Norway, Sweden and many others. (Peacejournalism.org 2013)

3.3 The Peace Journalism Model for journalists

Galtung’s (2002) model of peace journalism builds on contradictory approaches; ‘war journalism’ and ‘peace journalism’. War journalism is violence-oriented, propaganda-oriented, elite-oriented and victory-oriented. This approach is often linked to a dualistic approach, a zero-sum game where the winner takes all. A potential consequence is that war journalism contributes to escalating conflicts by reproducing propaganda, promoting war. On the other hand, Peace journalism approach has a moral and ethical point, acknowledging the fact that media itself play a role in the propaganda war. It presents a conscious choice to identify other options for the readers, viewers by offering a solution-oriented, people-oriented and truth-oriented approach, and this in turn implies a focus on possible suggestions for peace that the parties to the conflict might have an interest in hiding. Peace journalism is people-oriented in the sense that it focuses on the victims; thus gives a voice to the voiceless. It is also truth-oriented, in the sense that it reveals untruth on all sides and focuses on propaganda as a mean of continuing the war. (Peleg 2006)

Since 2001 ‘Reportingtheworld’, a platform consisting of working journalists, editors, academic, researcher and activist, joined a critical discussion about conflict reporting and peace journalism and after some fruitful dialogues and reflections, sets out a peace journalism model into the following set of questions to ask of any piece of conflict reporting in UK media, which can be adopted media elsewhere too with obvious adjustments (Lynch 2012):

- How is violence explained?

- What is the shape of the conflict?

- Is there any news of any efforts or ideas to resolve the conflict?

- What is the role of Britain; ‘the West’; the ‘international community’ in this story?

How to practice peace journalism

Derived from Lynch and McGoldrick’s 17 point plan for practicing peace journalism Robie (2011) has shorted them in 4 points;

- Avoid what divides parties, on the differences between what each says they want. Instead, try asking questions that may reveal areas of common ground.

- Avoid focusing exclusively on the suffering, fear and grievance of only one party. Instead, treat as equally newsworthy the suffering, fear and grievance of all parties.

- Avoid ‘victimizing’ language like ‘devastated’, ‘defenseless’, ‘pathetic’, ‘tragedy’, which tells us only what has been done to and could be done for a group of people by others. Instead, report on what has been done and could be done by the people.

- Avoid focusing exclusively on the human rights abuses, misdemeanors and wrongdoings of only one side. Instead, try to name all wrong-doers and treat allegations made by all the parties in a conflict equally.

Professor Dr Ronald Tuschl (2013) finds 10 Rules of Peace Journalism based on Vincent and Galtung,s theory of Peace Journalism; Peace Journalism Should

- Report a story from different perspectives

- Try to get access to events people and topics in warfare

- Try to avoid “elites” for reporting and find different experts and authorities instead

- Try to avoid a glorification of technologies

- Not avoid “Blood and guts stories” even though some viewers may find this disturbing or inhuman

- Involve also “Common People” to personalize the story

- Report different stories including background information

- Always be aware that “opinion leaders” are trying to manipulate them

- Avoid becoming the leading part of own story

- Always refer to peace initiatives and potential conflict resolution

In a society like Bangladesh where each and every news papers or TV change owned by either individual who is political and ideological interests or by the state. And therefore journalists should follow the role of the institution and their news report should go under its owner’s editorial policy.

3.4 Traditional Journalism vs. Peace Journalism

Professor Komagum developed the examples of peace journalism, based on stories that he hears and read in Uganda, these samples illustrate the differences between how stories are framed in traditional reporting as compared to conflict sensitive/peace reporting. (Youngblood 2009)

I am going to keep the story unchanged in order to understand better the importance of the example.

Traditional reporting – A news story in Uganda about election campaign:

Moses Akena, the Green Party Presidential Candidate of Gatu City said yesterday that Blue Party nominee Steven Oguti has been stealing money from the state treasury for many years, and that’s why Oguti has been able to afford nice cars and fancy vacations. “This kind of thievery is typical of people from his tribe,” Akena observed. “It is clear that Oguti and those like him are no-good snakes.” Further, Akena said that Oguti’s corruption will extend to the upcoming election. “We know if he wins, that he will be cheating. Now the question is, what will we do about this? Will we stand by and let him steal from us?”

Akena promises to tarmac (pave) 1,000 km of roads per year if elected and will hire 2,000 more primary school teachers when they come to power.

What’s wrong with this story?

- Its unbalanced, one sided, one source

- It encourages tribalism and divisions

- It could possible incite violence

- The reporter is being used to spread political propaganda, rumors

- Claims are presented as facts; no proof of these charges is given

- The story is unfair-the accused is not given a chance to respond

- Akena is not held accountable for his statements-How will he pay for

the new roads and teachers? How much will these things cost? - The story gives the impression that there are only two candidates.

How the same story can be made with peace journalism approach:

Two of Gatu city’s presidential candidates continue to engage in a campaign of mudslinging while two other candidates yesterday pledged to stick to issues.

At a press conference yesterday, Green Party Presidential Candidate Moses Akena made unsubstantiated charges against Blue Party nominee Steven Oguti, one of his opponents. Akena did briefly discuss his platform, including promises to tarmac 1,000 km of roads and hire 2,000 more primary teachers, but did not explain how or if these projects could be financially realized.

Meanwhile, Oguti responded with similar personal attacks against Akena. When pressed about roads and schools, he promised to issue a manifesto on these issues tomorrow.

Voters interviewed are tired of the mudslinging. Gatu City resident Stephanie Mulumba said, “I wish they’d talk about things that really matter. How can I afford to send my son to school? That’s what I really care about.” As Oguti finished meeting the press, Purple Party candidate Alex Busiga and Orange Party candidate Betty Aciro held their own joint press conference where they pledged to discuss issues this election. “The people want to know about roads and hospitals, and that’s what I’m going to talk about,” Aciro said. However, neither candidate was ready to discuss their positions on these issues in detail.

Why is this story better?

- It is balanced among many parties, and uses multiple sources

- Personal attacks are not aired

- There is no name calling or tribalism, nor is violence incited

- Claims are not presented as facts

- More prominent play is given to real issues that affect people

- Voices from voters, everyday people are used

- Promises are exposed with costs and feasibility

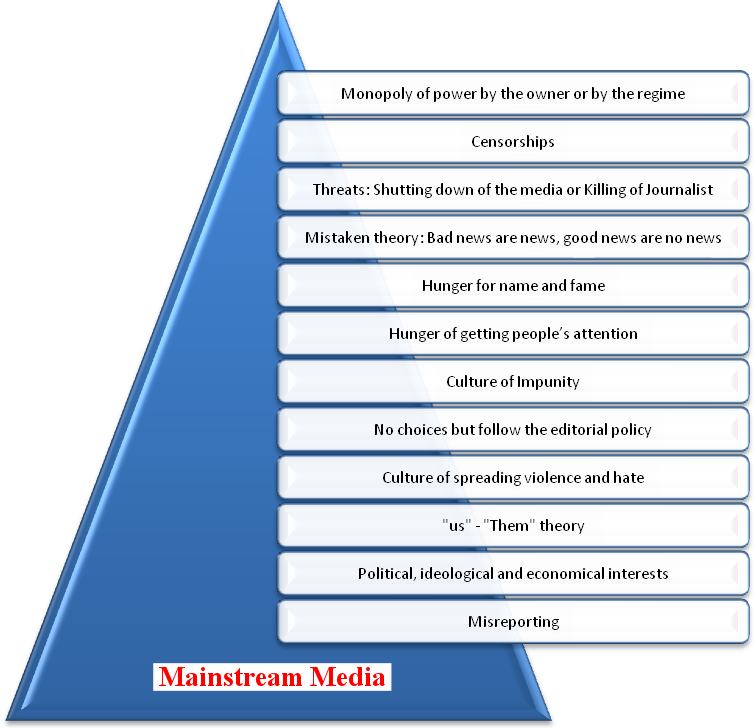

4. Part two: Why Peace Journalism is not being practiced in mainstream Media

Hypothesis: Political ideological economical interests, Regime’s control, owner’s power, hunger for name and fame, and among other factors cause mainstream media not to practice Peace Journalism.

In this section we will elaborate a bit on some of the factors and events to support my hypothesis.

4.1 Monopoly of power by the regime or by the owner of the Media Company

From my understanding, it doesn’t matter either it is a local media or international media, in the USA, or UK or in Bangladesh, a media company owned by the state or some individual. So a Media house has their own editorial policy, how they broadcast or publish their news’s, and news angel, theme, influenced by their ideological, political or economical interest. While my stay in the USA, I have observed that, US national version of CNN is very different than CNN world version. People within the USA doesn’t know much about the factors behind the suicide bombing in Afghanistan, all they know is that their sons, American soldiers are fighting in Afghanistan to save innocent Afghan civilian from Taliban. They do not know if Taliban has political motivation, why Taliban do not like American soldiers. Because CNN’s domestic version does not broadcast such news that would reveal other side of Afghan conflict.

A journalist working in mainstream Media has no choice but produce news report that goes within the policy of the particular media house. He or She cannot make a report that goes against their interest. Therefore I think peace journalism cannot work, because the regime or the individual owner of the Media house will not give up their interests. Many media house has been shuttled down in Bangladesh because they had on aired news that harmed regime’s reputation which I have elaborated in this paper below.

What if Journalists and editors are given the choice to make their own in presenting and preparing news report? I would argue even in such case, journalists himself would have own ideology, faith and political belief that would influence in their news report, unless obviously if the news reporter wanted to be neutral and peace initiator.

Taking Lynch’s analysis of peace journalism, a journalist tries to report on the underlying causes of violence or conflict, but Media and News houses are not often tend to do so or they are not allowed to do so. For example, American media report on Afghan war tend to establish an image that US soldiers are hero’s combating terrorism, saving afghan people. Often tries to get legitimacy that the killing of Afghan civilians by US soldiers are right thing to do. They try to say that the enemies are killing our sons; therefore Media try to create a hateful image towards the US opponent. But they do not see that US soldiers are killing other people’s sons too.

4.2 The Reality in the mainstream media

Reporting violence without background or context would mean misrepresent the news, since any conflict is, at root, a relationship, of parties setting and pursuing incompatible goals. And so omit any discussion of these factors is a distortion. (Lynch 2005)

To me, in traditional news reporting journalists are so much after the notion of “Breaking News”. It is true that viewers also eager for breaking news. Therefore when any violence takes places media trends to report on going updates and they try to create a tension in their news presentation, so that audiences would not leave their news outlets. For example when, Connecticut school shooting occurred in the US or Violence erupted in Tahrir square in Cairo. Medias were showing every single bit of ongoing happenings, TV channels were showing long period of ‘live’. Not any Medias were interested at that time to make news reports of root causes of the violence. Maybe audiences are also eagerly waiting to see the new happenings not the historical background or any root cause of the violence. Therefore media’s where showing the deaths, bloods, cries etc.

So here peace journalism would find the root cause of the violence i.e. with the Connecticut school shooting, the US domestic gun policy, weather every individual having guns was a right thing or not.

Lynch believes that Media often force its audience interpret things which he calls “decoding” as the way it serve to certain group or governments. It is because people often see things as show by media by image or messages through news. Thus it creates an image in peoples thinking. Decoding is something we often do automatically, as so much of what we read, hear and see is familiar, for example, establishing Saddam Hussein of Iraq as a bad man. Whereas peace journalism would view all other things; i.e. all the reality, both subsequent and previous, tends. (Lynch 2005)

According to Hackett, it seems probable that in Western corporate media, journalists have neither sufficient motivation, nor autonomy vis-à-vis their employers, to transform the way news is done, without support from powerful external allies. (2006) American Scholar Chomsky have examined the ideological content of peace reporting by the U.S. media and asserted that U.S. evocations of peace are strategically employed not to support peace but to cast a “saintly glow” over American aggression (1999). Media representations of peace are defensive, presenting peace as the military protection of “our” borders against evil incursions.

4.3 “Will the Syrian conflict spark World War III?”

“Will the Syrian conflict spark World War III?” This is a news headline on an online news outlet, which grabbed my attention and immediately I clicked the headline to read the whole story. It was published on September 6, when the Syrian conflict was mounting the global tension. This was a follow up news after when Syrian deputy foreign minister made a warning statement that the Syrian regime will not remain silent in its response to any U.S.-led attack, even if it leads to World War III. (Arabiya 2013)

My argument here is that, such a news headlines creates tension among the readers and maybe among the states or involving actors.

While working as a journalist I attended quite a few professional journalism training. Trainer told us a news headlines must be very attractive and catchy to grab readers attention. Even it is much more obvious in today’s online media world. You got thousands of online news wires; if your headline is not attractive readers won’t click it.

Journalists are often eager to make their news story famous and they do make such news headlines, even they try to make controversial news so that it creates an outrage. Such a practice is very common in mainstream media. This practice can fuel conflict, tension and violence I would say.

Even though the journalist in the Syrian news falsified his headline in the body of the report “of course, this is nonsense; neither the downfall of Assad’s regime, nor a Western conflict nor the reaction of Assad’s allies at its worst, could spark a war beyond the skies of the region” ( Rashed 2013), but I do think that such mews headlines only create tension yet leaving no peace initiatives.

4.4 The Philippines – peace journalism in a culture of impunity

One of the cradles of the progress of peace journalism studies has been in the Philippines, where advocates of the discipline have been forced to contend with both a culture of suspicion due to collective insurgency being waged by the New People’s Army (NPA) against the authorities and a culture of impunity over the widespread murders of news workers, activists, and civil and human rights advocates. (Rabie 2011)

One of the ‘freest and least fettered’ media systems in Asia (Patindol 2010), the Philippines also ranks as one of the most dangerous countries for news media, after Iraq, because of the high death rate of local journalists. Journalists have been assassinated in the Philippines with impunity for almost a quarter of a century ever since the end of martial law and the flight of ousted Dictator Ferdinand Marcos into exile in 1986. Media played a critical role in the civilian Revolution that led to the downfall of Dictator Marcos. In more than 23years since democracy was restored, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines recorded136 killings of journalists, an average of one kills every two months (Arao 2010). Study shows that the killings of the journalists have worsened under the Macapagal Arroyo administration as an average of one journalist got murdered every month during 2001 – 2009 period (ibid 2011).

In the situation of such killings of journalists, academia’s and researchers were examining how to find a way to develop the practice of peace journalism as a discipline when practitioners are faced with opposition, ‘not just from individuals and groups but from the entire media system itself’ (Patindol 2010).

In 2004 the formation of the Peace and Conflict Journalism Network (PECOJON) consisting of journalists, academia and the media professional was an attempt to building solidarity as they jointly work towards implementing peace journalism in the mainstream media.(IBID 2010) Since then, this movement has about 250 members in the Philippines and 165 members from 15 other nations.

But the uncontrolled killings of news people, particularly radio reporters and talk show hosts, have led to a debate about ethics and professionalism in the Filipino media. Columnist Danny Arao raised a key question in his weekly commentary in Asian Correspondent (2010); how should journalism be taught at a time when journalists are killed with impunity and the government remains hostile to press freedom? In Philippines Since 1986, 112 Journalists killed in the line of duty and 53 Journalists killed while not in the line of duty. (Cmfr-phil.org 2013)

4.5 Bangladesh: Journalists have no choice

If Peace Journalism means Journalists and Editors are given a choice to make reports on their own then I would argue there is no such things exists in Bangladesh. Because each and every TV channel or News paper are owned by either a political leader or a businessman who had direct or indirect involvement with any political party. Therefore media would have a policy that serves the government or any other political party.

Bangladesh has 50 nationwide dailies, of which eight are English-language newspapers; 25 television channels; seven FM radio stations; 14 community radio channels and over 300 regional magazines published in English and Bengali; however beneath this impressive statistics, Haq argues that journalists in Bangladesh are in fear of impunity and abuse.

New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists -CPJ (2013)have ranked Bangladesh the world’s 19th deadliest country for media, because of political pressure, censorship, arrests, detention, torture in custody, closure of media outlets and extrajudicial killings as the most salient examples of a systematic attack on the Media.

Since 1992, 21 journalists have been killed 3 of them were during the first half of 2013, 120 media practitioners were subjected to severe attacks and 24 received some form of threat. Present ruling government had closed down 3 TV channels accusing of “airing provocative programmers that fuels public sentiment.”(CPJ 2013)

State owned Media such as TV and Radio are propaganda machine, because state media never broadcast any news that criticizes the government. One of the most effective means for the ruling political party to control the nation was through manipulation of the news media. In the 1980s, the government’s National Broadcasting Authority monopolized telecommunications within the country. Thus the party that controlled the government effectively decided the content of the country’s broadcasts. (Heitzman & Worden 1989)

On the other hand, privet TV channels and news papers are owned by either political leader or business man who is also belong to any political ideology. Therefore the editorial policy of Bangladesh TV channels and News papers are always politically motivated and can never be unbiased.

Ruling regimes always been oppressed the media by exercising press censorship banning certain publications for extended periods of time to officially pressuring publishers to regulate the content of news articles. (Heitzman & Worden 1989) The Bangladesh Observer was banned for three months in 1987, and the weekly Banglar Bani was banned through much of 1987 and 1988. The weekly Joyjatra was banned in February 1988. In 1988 the government closed the Dainik Khabor for ten weeks under the Special Powers Act of 1974 because the newspaper had released an article with a map making Bangladesh look like part of India, thus inflicting “injury to the independence and sovereignty of the country.” (Heitzman & Worden 1989)

The operations of the British Broadcasting Corporation- BBC were banned under the Special Powers Act from December 14, 1987, to May 2, 1988, and one of its correspondents was jailed for allegedly having manufactured “continuing hostile and tendentious propaganda.”( Heitzman & Worden 1989)

4.6 International Media and Bangladeshi extremism

During the first week of March 2013, 500,000 activists and leaders of the Hefazat e Islam of Bangladesh – HIB consist of Qoumi Madrasha students and teachers, clogged the streets of Dhaka, demanding their 13 agendas to be implemented in the state constitution which many of them go against women empowerment. About 50 people were killed during 5 May clashes. (NY Times 2013)

International Media like BBC, CNN, NY Times, Washington Post, etc covered the incidents, besides many highlighted the event as Islamic fundamentalism and extremism, many said that Bangladesh is becoming like Taliban of Afghanistan, many trying to find a connection of global terrorism in Bangladesh etc. But the reality is the members of HIB are students and teachers of Islamic religious school call “Qoumi Madrasha”. It would have been the “Peace Journalism” if Media were finding the factors and background behind the rise of this group, rather than making big news headlines. I mean the root causes and circumstances, why they do not want women empowerment.

One other thing, International Media made headlines about the extremism in Bangladesh, but no media made headlines, the fact that months after the incident, people of other religion such as Hindus, Buddhists have been celebrating their religious festivities with peaceful and happy atmosphere. This would portray Bangladesh a society where different religious communities live in harmony even though 90% of the Bangladeshi population is Muslim.

4.7 Reporting “War on Terror”- the problem with the traditional journalism

Lynch (2002) identified the following problems with the news coverage of global media on the “War on Terror;

- New reports that portray ‘you are either with us, or you are with the terrorists’, is to give a template for framing any and every conflict as a tug-of-war, a zero-sum game of two parties. It unavoidably prepares the ground for escalation of violence.

- News reports create such an atmosphere so that people think of a conflict as having only two parties, they can feel they are faced with only two alternatives; victory or defeat.

- Defeat being unthinkable, therefore, each party steps up its efforts for victory. Relations between them deteriorate, and there is an escalation of violence. This may further establish the ‘us and them’ mentality, causing gradually growing numbers of people to ‘take sides’.

- Goals become formulated as demands to distinguish and divide each party from the other. Demands harden into a ‘platform’ or position, which can only be accomplished through victory.

Lynch (2002) argues that the War on Terror is a media strategy as well as a military one. If journalists could see how conflict is being constructed, they could also find peace initiatives in their news reporting. He believes that there been plenty of options to create alternative journalism in this topic, i.e. “If the 9/11 attacks can be interpreted as ‘blowback’ from US foreign policies, what are they and how do they work? What are the connections?” or “What made young men from UK Muslim communities join Osama bin Laden?” (Lynch 2002)

Andrew Gowers(2002) editor of Financial Times argues that The US Administration projects a world view in very simple and clear terms – ‘the War on Terrorism’; the ‘Axis of Evil’. But when you scratch the surface you find they are far from simple and very far from clear. There is a huge division between the world view of Americans and Europeans, in particular in the context of terrorism and the Middle East.

Brownwen Maddox(2002), foreign editor of the Time claims that the US Administration is highly secretive – it gives out a lot of material but very little information “It’s outrageous how little we know about the identity or supposed complicity in terrorism of the 300 or so detainees of Guantanamo Bay, it has proven impossible to find out anything about them”.

Zoe Young (2002) believes that mainstream media did not take on the issue of oil as a factor in this conflict; US wanted its pipeline across central Asia and Afghanistan was not going to be allowed to get in the way; that’s an angle people are learning about from alternative Media and the mainstream media’s refusal to engage with it spoil the reputation of them in people’s eyes.

Afghan Academic Dr, Ali Wardak (2002) claims that each media house has their own political ideology and their news influenced by it “I think it is more important to ask how a particular channel reports the war on terrorism, how does a particular newspaper report the war? Since September 11th I have been reading almost every main UK newspaper and have found the Times and the Financial Times to be of a very high standard and highly professional in their work. But, their political correctness tends to shadow their reports and what actually happens in the real world. I have found the Daily Telegraph to be representing a particular ideology and its reports seem to be strongly influenced by this. This sometimes resulted in the distortion of facts about the war on terrorism, and I was amazed to read that.”

4.8 Israel and the Palestinians: A Misreported Conflict

“Television coverage of the Israel-Palestine conflict tends to reflect Israeli perspectives, while leaving most viewers alarmingly ill-informed” – (Philo 2004).

Based on polls and interview with 800 people over a two-year period, and analysis of more than 200 news programs, the Glasgow University study found that Bad News from Israel, spells out the exact match between patterns of omission and distortion in coverage of Israel-Palestine conflict, thereafter the wrongheadedness of the audience.(Philo 2004) Many British people believe ‘the settlers’ are Palestinian, than know they are Israeli, a large number of them think it’s the Palestinians who are occupying the occupied territories, and many have only the vaguest idea of where ‘the refugees’ come from.

Ewen MacAskill, Diplomatic Editor of the Guardian, said that he had no appreciation of the conditions of everyday life under occupation until he visited the West Bank and saw the poverty for himself. Tim Llewellyn former BBC Middle East Correspondent claims that a tone in daily domestic TV reporting that implies and encourages viewers in the belief that the Palestinians are a headless bunch of fanatics and no-hopers given to violence endemically and inherently, who are carrying out with enormous ingratitude, impertinence and hostility, aggressive and unprovoked assaults on a legal government that is trying its best for all the people under its control. Lyse Doucet, Middle East correspondent At the BBC says even though there’s no doubt in my mind that the Palestinians are suffering far more in this present conflict, every day they’re suffering. Their children can’t get to schools; their impoverishment takes place on a daily basis. Israelis in Tel Aviv are not suffering this, Israelis in other parts of Israel are not, but that doesn’t matter. The perception of Israelis is that they’re suffering – that they’ve been betrayed and that is something that I think we have to reflect. It is the perceptions as well as historical rights and wrongs that are fueling this conflict. (Reporting the World 2013)

- Conclusion

As of my research question “why Peace Journalism is not been practiced in mainstream media?” – I did an analysis of two major events i.e. “war on terror” and “Israel –Palestine Conflict”. I also discussed about some other factors to support my argument. I have showed that the Regime apply power over media houses, and owner of the media house sets the editorial policy about the news headlines, new angle, or what story they should cover. From the Individual level a journalist often has the tendency to become famous, and they do make controversial news headlines which often fuel violence.

Mainstream media always been fueling tension over the conflict evens such 9/11, Afghan war, the escalating violence between Israel and the Palestine, possible nuclear war between India and Pakistan etc.( Hackett 2006) We have also seen in 1994 Rwanda massacre how the hate radio spread the violence.

Alternative Media like individual blog, Website, Social Media, YouTube, Face Book are of course new platform for Peace Journalism, regardless of financial resources. And these tools has been shaping up our societies enormously, there is no doubt about that. But still people are depending on mainstream media. When people get up in the morning, they want to take a cup of coffee and sit on the sofa, watch the morning show on TV, or take a look on news headlines of the news paper they get on a regular basis. Similarly in the evening, after the supper, people like to watch the evening news, which is very important for them. Therefore not many people look for the alternative news on YouTube or elsewhere on the internet.

However it is much more obvious that societies that experienced violence and massacre should practice Peace Journalism to rebuild the society. But reality in many countries is that the financial crisis and cut backs in jobs in the news industry causing the potential of investigative and critical reporting in main stream media.

“Peace Journalism” is growing in the academic and research arena. Many Universities now have included it as a course. Many organization also doing research, giving training and doing campaign. These are positive aspects.

Peace Journalism is when editors and reporters make choices – of what to report, and how to report. But I think it is also that not only they are given the choice but also that they are motivated to make news reports that find a solution or at least tries to establish a peaceful transition and not fueling the violence.

Just a mere word can spoil the whole peace negotiation or explode the violence conflict. Therefore journalist himself has a responsibility in which way he must represent the news. But in many cases he has a hunger for getting his news on the lead, therefore he misleads the information.

We have discussed the reasons and factors why peace journalism is not working in the mainstream media. Like in the case of Bangladesh, journalist and media house has no choice but follow the rules that are set by the owner. In Philippine itt is extremely risky to report against the powerful elites.

Cases like “War or terror” and “Israel- Palestine conflict” we have seen that media houses are driven by their political, economical and ideological interests that influence on what they produce. I can’t say that there won’t be much practice of peace Journalism in mainstream media, but I do not know when it will happen. But one thing is for sure, people are losing their trust on mainstream media. Today they look for the truth on social media or elsewhere on the internet based alternative media.

References and Bibliographies:

“Americans for Peace Now.” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://www.peacenow.org/.

“Associate Professor Jake Lynch – The University of Sydney.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://sydney.edu.au/arts/peace_conflict/staff/profiles/jake.lynch.php.

“Bangladesh – THE MEDIA.” Accessed October 20, 2013. http://countrystudies.us/bangladesh/104.htm.

“Bangladesh’s Radical Muslims Uniting Behind Hefazat-e-Islam | World News | Guardian Weekly.” Accessed September 30, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/30/bangladesh-hefazat-e-islam-shah-ahmad-shafi.

“BBC NEWS | South Asia | Mudslides Kill Many in Bangladesh.” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6739889.stm.

Becker, Jorg, 1982: ‘Communication and Peace: The Empirical and Theoretical Relation between Two Categories in Social Sciences’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 227-240.

“Center for Global Peace Journalism.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.park.edu/center-for-peace-journalism/resources.html.

“Center for Media Justice : Messaging, Framing and Strategy.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://centerformediajustice.org/toolbox/strategy-tools/.

“Center for Global Peace Journalism.” Accessed October 21, 2013. http://www.park.edu/center-for-peace-journalism/resources.html.

“Conflict Reporting in the South Pacific: Why Peace Journalism Has a Chance.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.academia.edu/1374720/Conflict_reporting_in_the_South_Pacific_Why_peace_journalism_has_a_chance.

“Crisis Reporting Centre – Institute for War and Peace Reporting.” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://iwpr.net/what-we-do/crisis-reporting-centre.

“CMFR | Journalists Killed in the Philippines.” Accessed October 20, 2013. http://www.cmfr-phil.org/map/index_inline.html.

“English.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://home.hio.no/~rune/english.htm.

“Friedensnews.at.” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://www.friedensnews.at/.

Frohlich, G. (2004). Emotional intelligence in Peace Journalism., Master of Arts Thesis. European University Center for Peace Studies, pp.17, 47.

From Uganda Peace Journalism Project 2010-11. Accessed October 29, 2013. http://stevenlyoungblood59448.podomatic.com/entry/2013-03-26T09_28_32-07_00.

Galtung, Johan. ”Peace journalism – a challenge’”. In Journalism and the New World Order, Vol.2. Studying the War and the Media, edited by Kempf, W. and H. Loustarinen Gothenburg: Nordicom, 2002.

Galtung, J. & Ruge, M. (1965). The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2, pp. 64–91;

Galtung, Johan and Tschudi, Finn, 2001: ‘Crafting Peace: On the Psychology of the TRANSCEND Approach’ in eds D. J. Christie, R. V. Wagner and D. D. Winter D. D., Peace, Conflict, and Violence, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 210-222.

Hackett, R.A. “Is Peace Journalism Possible? Three Frameworks for Assessing Structure and Agency in News Media” . In Conflict & Communication online, Vol.5, No.2, 2006 http://www.cco.regener-online.de/2006_2/pdf/hackett.pdf

Hackett, R.A. and B. Schroeder. ”Does Anybody Practice Peace Journalism? A Cross-National Comparison of Press Coverage of the Afghanistan and Israeli-Hezbollah Wars”, Peace and Policy Vol. 13, (2008): 26-47.

Howard, R. (n.d.). Conflict Sensitive Journalism in Practice. Center for Journalism Ethics: School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

“Home » International Media Support (IMS).” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.i-m-s.dk/.

“Human Rights and Journalism.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.park.edu/center-for-peace-journalism/_documents/_resources/12_iwpr_human%20rights%20rept.pdf.

“Independent Media Center | Www.indymedia.org | ((( i ))).” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://www.indymedia.org/or/index.shtml.

“Institute of Innovative Media & E-Journalism (IIMEJ).” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://www.iimej.com/.

“Institute for War and Peace Reporting -.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://iwpr.net/.

International Communication Association, TBA, Boston, MA. http://citation.allacademic.com/meta/p489404_index.html

“Israel and the Palestinians.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.reportingtheworld.net/Israel_Palestine.html.

“IPS – Fourth Estate Under Fire in Bangladesh | Inter Press Service.” Accessed October 20, 2013. http://www.ipsnews.net/2013/07/fourth-estate-under-fire-in-bangladesh/.

James, Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors. Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1989.

“Lebanon Peace Journalism – Steven L. Youngblood – Picasa Web Albums.” Accessed October 29, 2013. https://picasaweb.google.com/112712325175001400466/LebanonPeaceJournalism.

Lynch, Jake. “Jake Lynch: Can You Trust a Journalist? | World News | Observer.co.uk,” June 9, 2002. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/jun/09/2.

Lynch, Jake.“Reporting the World – A practical checklist for the ethical reporting of conflicts in the 21st Century produced by journalists for journalists”. 2002. Published by Conflict & Peace Forums. Taplow Court, Taplow, Berkshire SL6 OER.

Lynch, Jake & Galtung, Johan. “Reporting Conflict: New Directions in Peace Journalism ”University of Queensland Press, 2010.

Lynch, Jake and McGoldrick, Annabel, 2001: ‘Peace journalism in Poso’, Inside Indonesia No. 66.

Loyn D. ”Good journalism or Peace Journalism”. In Conflict & Communication online. Vol. 6, no. 2, (2007), http://www.cco.regener-online.de/

Lynch, J and A. McGoldrick. Peace Journalism. Hawthorne Press, 2005.

Lynch, J 2007. ”Peace Journalism and its discontents” In Conflict & Communication online. Vol. 6, no. 2, (2007), http://www.cco.regener-online.de/

Lynch J. Debates in Peace Journalism. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008.

Lynch, J. & Galtung, J. (2010). Reporting conflict: New directions in peace journalism. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, pp. 12–14.

Loyn, David. “Good journalism or peace journalism?”. 2007. Conflict & communication online, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2007. ISSN 1618-0747www.cco.regener-online.de

MacBride, Sean, 1980: Many Voices, One World: Report of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, Paris: UNESCO.

“Measuring Peace in the Media 2011 Report.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.visionofhumanity.org/sites/default/files/Measuring%20Peace%20in%20the%20Media%202011%20Report_0.pdf.

Naveh, Chanan. “The Role of the Media in Foreign Policy Decision-Making”. Conflict & communication online, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2002. ISSN 1618-0747. www.cco.regener-online.de

Noam Chomsky. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon.

Ottosen, Rune. “The war in Afghanistan and peace journalism in practice”.2010. Media, War & Conflict http://mwc.sagepub.com/content/3/3/261

“PEACE JOURNALISM FOR JOURNALISTS.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.transcend.org/tms/about-peace-journalism/2-peace-journalism-for-journalists/.

Peace Journalism Part 1, 2008. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jg9YPYBtpsY.

“PEACE JOURNALISM.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.peacejournalism.org/Peace_Journalism/Welcome.html.

“Peace Journalism – Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies – The University of Sydney.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://sydney.edu.au/arts/peace_conflict/research/peace_journalism.shtml.

“Peace Media: Conflict Transformation through Mass Media.” Accessed October 30, 2013. http://vladob.wordpress.com/.

Peleg, Samuel. “Peace Journalism through the Lense of Conflict Theory: Analysis and Practice” Conflict & communication online, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2006. ISSN 1618-0747.www.cco.regener-online.de.

Philo, Greg. “Greg Philo: What You Get in 20 Seconds,” July 14, 2004. http://www.theguardian.com/media/2004/jul/14/israel.middleeastthemedia.

“Reporting the War on Terror.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.reportingtheworld.net/War_on_Terror.html.

“Reporting the World.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.reportingtheworld.net/Homepage.html.

Robie, David. “Conflict Reporting in the South Pacific: Why Peace Journalism Has a Chance,” December 2, 2011. http://www.academia.edu/1374720/Conflict_reporting_in_the_South_Pacific_Why_peace_journalism_has_a_chance.

Ross, Susan Dente. “Constructing Conflict: A Focused Review of War and Peace Journalism”. Conflict & communication online, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2006. ISSN 1618-0747.www.cco.regener-online.de.

“Seeds of Peace.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.seedsofpeace.org/.

Solomon, W.S. (1992). New Frames and Media Packages: Covering El Salvador. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 9, 56-74.

Stone, S.D. (1989). The Peace Movement and Toronto Newspapers. The Canadian Journal of Communication, 14:1, 57-69.

“United States Institute of Peace.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.usip.org/.

“Welcome – PECOJON International.” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://pecojon.org/.

“WHAT IS PEACE JOURNALISM?” Accessed October 29, 2013. http://www.transcend.org/tms/about-peace-journalism/1-what-is-peace-journalism/.

“Will the Syrian Conflict Spark World War III? – Alarabiya.net English | Front Page.” Accessed October 31, 2013. http://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle-east/2013/09/07/Will-the-Syrian-conflict-spark-World-War-III-.html.

Workneh, T. W. , 2011-05-25 “War Journalism or Peace Journalism? A Case Study of U.S. and British Newspapers’ Coverage of the Somali Conflict” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the

Youngblood, Steven “PJ: The Academic Debate”. 2009. Park University.

* Dr Ronald Tuschl conducted a lecture on Peace Journalism at the European Peace University – EPU, Austria during 22-26 July 2013.

_______________________________________

Meah Mostafiz, doctoral candidate in Political Science at the University of Heidelberg Germany, MA in Peace and Conflict Studies at the European Peace University–EPU, Austria. Prior to that he worked as a Journalist in Bangladesh, and did Internship with the International Criminal Court–ICC in The Hague. He can be reached at mostafiz@uni-heidelberg.de

Meah Mostafiz, doctoral candidate in Political Science at the University of Heidelberg Germany, MA in Peace and Conflict Studies at the European Peace University–EPU, Austria. Prior to that he worked as a Journalist in Bangladesh, and did Internship with the International Criminal Court–ICC in The Hague. He can be reached at mostafiz@uni-heidelberg.de

Paper written on 31 October 2013. Revised in July 2015.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 19 Jun 2017.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Journalism – A Global Debate, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: