The Settlers’ Goal Is Not the Settlements – It Is the Total Transformation of Israel

PALESTINE - ISRAEL, 26 Jun 2017

Noam Sheizaf | +972 Mag – TRANSCEND Media Service

Protesters attend a demonstration against the demolition of nine homes in the West Bank settlement of Ofra, February 5, 2017. (Tomer Neuberg/Flash90)

8 Jun 2017 – The settlements, the settlers, and the occupation are all entirely associated with one another in the Israeli consciousness. The Left and the Right agree on this, albeit with varying considerations: the Left wants to apportion blame for Israel’s continuing control over the West Bank, while the settlers want to take credit for the settlement project and for thwarting the idea of partitioning the land.

The image of the settler leadership as ideological extremists suits everyone — even the international community, which has accustomed itself to an artificial distinction between “good” and democratic Israel, which is embraced and respected, and bad “settler” Israel.

But this discourse is disconnected from reality. The occupation has persisted not because of the settlers, but because of the actions of the state — in which all of Israeli society participates. The settler leadership is highly pragmatic, enabling it to adopt whichever political position prevails vis-a-vis the settlement enterprise in the Israeli political discourse. Under certain political circumstances, this pragmatism makes possible the evacuation of settlements. Settling the land is not at all the settlers’ true goal, and I’ll explain why.

The first settlement was established in Gush Etzion immediately following the Six-Day War in 1967. There were no real political disagreements over its founding, because it was thought of as a “return” to a site that had been lost 19 years earlier during the 1948 War. The following year saw an attempt at establishing a settlement in Hebron, eventually leading to the founding of Kiryat Arba (Jews only began properly residing in the Palestinian city after Likud took power in 1977). Most of the settlements that sprung up in those early years were in the Jordan Valley, and were in fact established by the Labor Zionists of the Mapai party.

This last point is significant: there has never been a debate in Israel over establishing settlements, and every single government since the occupation began has built beyond the Green Line. Rather, the debate has been over where to build — or, to be more exact, who will decide where settlements should be built. As such, the term “settler” has never been applied to people living in the Jordan Valley, just as the Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem have never been deemed “settlements.”

In the Israeli consciousness, “settlers” are the people who, after 1973’s Yom Kippur War, organized themselves into movements such as Gush Emunim, the Yesha Council, and the National Religious Party (Mafdal). This association, which we don’t pay enough attention to, is at the heart of the matter. The term “settlers” is a codeword for religious-Zionism (politically-speaking, not statistically), and the dispute over the occupied territories is part of an internal power-struggle within Jewish society.

Evicted residents of the settler outpost Amona cry after their caravan homes are demolished, a few days after residents were evicted, February 7, 2017. (Nati Shohat/Flash90)

Gush Emunim was formed in 1974, but its roots stretch back much further, to the first decade of the state and groups of religious youngsters who attended yeshiva together. The most famous among them was established in Israel’s central Sharon region in the 1950s, and its members attended the Merkaz HaRav Yeshiva in Jerusalem (then a fringe institution). Over the years, they would form the definitive image of the settler movement.

For the religious youth who came of age at the end of the ‘50s and early ‘60s, there was likely nothing more frustrating than the agreements which led to religious Zionism becoming Mapai’s, and the state’s, kosher supervisors. The very people who saw themselves as a part of an avant-garde that merged Judaism with a modern state, and who were therefore supposed to lead the Jewish nation, were pushed to the political margins. They were assigned the task of rummaging around in army kitchens, while the Labor elite kept the role of decision-making on national security and distribution of resources to itself. Even the role of the opposition had been snatched up by the Revisionists — Ashkenazi secularists, just the Mapainiks. The ultra-Orthodox were afforded respect despite turning their backs on Zionism. But religious Zionism’s alliance with the state brought it no political gain.

This fact is as important as Gush Emunim’s ideology itself. There is no study of or text on the settlers that doesn’t mention the “prophecy” of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, who on the eve of the Six-Day War lamented to his students over the future of our Hebron and Nablus.

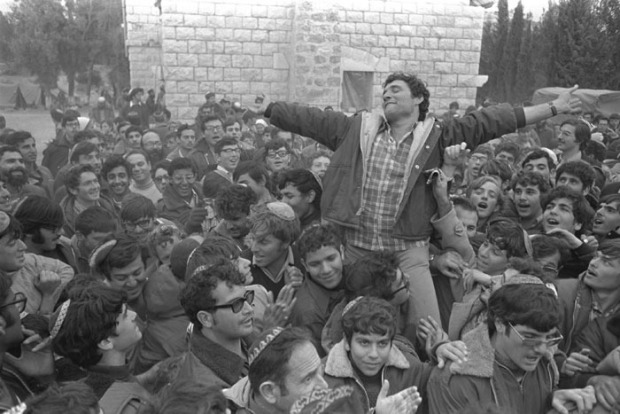

Gush Emunim leaders and supporters celebrating the Government’s decision to allow the first Jewish settlement in the Samaria region, 1974. Carried at the center is former MK Chanan Porat.

(photo: Moshe Milner / Government Press Office)

But the story of the settlements is above all one of religious Zionism’s journey from the sidelines in the early years of the state to its prominent position today — and not the story of Nablus, which is still not really ours. In other words, the occupied territories were, for religious Zionism, a means and not an end, and they remained so throughout the decades that followed the establishment of the first settlement.

As long as the Mapai was in a strong position, religious Zionism’s path was blocked. By the end of 1973, only a few hundred Jews had moved to the West Bank (including those in the Jordan Valley), while Hebron’s settlers were primarily located in the military governor’s compound in the city. The real political opportunities came following the crisis of the Yom Kippur War and the decline of the Labor movement and its satellite parties.

Gush Emunim, formed half a year after the war, instinctively understood the Mapai leadership’s weakness and weariness from pushing the settlements into new areas. In keeping with their ideology, Gush Emunim naturally took this task upon themselves; above all, however, it was a way for them to leave behind their status of food inspectors and move toward Zionism’s center-stage — with its primary goal of driving out the Arabs for the benefit of the Jewish population. In fact, the Labor Party was not Gush Emunim’s primary target — rather, it was the founding generation of Mafdal, which had become hooked on its role as Zionism’s spare tire.

That same Mapai weakness was also behind the then-belief of many Labor ideologues and political leaders that Gush Emunim was a positive force — one which could carry out duties that the secular class had tired of. Israeli cultural luminaries such as Yitzhak Tabenkin and Natan Alterman signed a petition in support of “Greater Israel”; Yigal Allon took the Hebron settlers under his wing; and Shimon Peres planted a tree in Ofra. But Gush Emunim’s members wanted to decide for themselves who would be a settler and where (on the mountaintops, among major Palestinian population centers); they wanted governing authority, and not just to be the settlements’ foot soldiers. Yitzhak Rabin’s weak and divided government couldn’t agree to this, but didn’t really resist either.

The religious Zionists were part of the right-wing coalition that took power when the Likud triumphed at the 1977 elections. The veteran Revisionists were behind the wheel, while Mizrahim, religious-Zionists — and later on Russians and the ultra-Orthodox — made up the rest of the bloc. But the settlers’ fringe position, even after the Right had taken power, brought further frustration, despite the rate of settlement-building rising dramatically under the Likud government.

The breaking point came with the evacuation of the Sinai following the Camp David Accords in 1978. For the first time, religious Zionism’s political aspirations came into conflict with its ideology: the question now was not only over relations with a right-wing government that had committed to remove the Sinai settlements — and even worse, grant autonomy to Palestinians in the territories — but over the state itself. This crisis birthed the Jewish Underground, whose members, unlike other Jewish terrorists, were part of the elite. The group counted leading figures among its numbers, and one can reasonably assume that many more were aware of the organization’s existence. Its emergence precipitated Gush Emunim’s gravest crisis.

The era of the Jewish Underground marks the only time in the history of the country in which the settler leadership broke the state’s rules, and took part in genuine messianic and revolutionary activities. One can only imagine how different history might have looked had their plan to blow up the Dome of the Rock, or their attempt in 1984 to bomb five buses full of Palestinians, had succeeded. Most interesting of all, however, is that for all the settlement evacuations and peace accords that followed, a moment of that nature never arose again.

A decade later settlers took to the front line again in protest of the Oslo Accords, although they largely kept their rebellion within democratic norms. Neither the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin nor the terror attack at Hebron’s Cave of the Patriarchs, had been part of their organized rebellion. For all their talk that killing in then name of the Land of Israel was legitimate, and all the prohibitions on handing over territory, the settler leadership and the vast majority of the public took the Israeli political rulebook far more seriously than they did halakhic edicts. The settlers entered coalitions that accepted the Oslo Accords, and negotiated over further settlement evacuations. The leadership instructed settlers not to confront IDF soldiers during the evacuation of Gush Katif in Gaza, which eventually passed without bloodshed.

Protesters burn tires at the entrance to the illegal outpost of Amona, on February 1, 2017.

(Hadas Parush/Flash90)

This template has since reappeared every time an outpost has been evacuated: settler opposition is entirely symbolic, and comes from fringe groups. The settler elite completely accepts the decisions of the Israeli government, and as settlers have become more integrated into Israel’s government and institutions, the consensus has only grown. Remarkably, even though there is endless talk in Israel of martyrdom or civil war, not a single shot has been fired during the evacuation of a Jewish settlement. That’s not because settlers are weak or not prepared to fight for their goals, but because the aim of religious Zionism is to lead the State of Israel, and not necessarily just to settle the land. Taking on the establishment would once again push them to the margins.

The last key moment for the settlers arrived not in the occupied territories, but in the transition of voters from the Jewish Home party to Likud, and the demise of the party’s Revisionist leaders, whose historical role had come to an end. The settlers no longer want to strike shady deals with Likud ministers at 2 a.m. The settler old guard are yesterday’s news, and their heirs are arriving through the front door.

The Right is now the dominant force in Israel, and the preeminent force on the Right is religious Zionism. The dream of those yeshiva students who would go on to form Gush Emunim has materialized — not in the West Bank and on its hilltops, but in Tel Aviv, the Ministry of Education, the media, and the army. This process has taken place inside the Green Line, with the settlements —isolated, uniform towns with independent education systems and a large public sector — serving as base camps. These communities, owing to their unique character and structure, are able to maintain ideological unity and a sense of a shared mission.

I am not arguing that the settlers are feigning, or that they’re willing to part with the territories in exchange for jobs and assets. But we need to differentiate between ideology and political aspirations, and realize that those aspirations will generally win out — among everyone, not just settlers. Ideology is more of a common language and guiding principle than a practical plan. Israel and the occupation are often spoken of in existential terms, yet we eventually come to accept the developments unfolding on the ground regardless of whether they meet our ideological standards. There is almost no resistance, either from the Left or the Right.

There are many phenomena in Israel that are put down to ideology when they are in fact the result of various political groups vying for resources. The religious Zionist movement’s decision to settle the frontier occupied in 1967 in order to advance its standing in Israel was by no means a historical precedent. More unique was the phenomenal success religious Zionism’s made of this process. Nonetheless it was ultimately Israel, and not Mafdal, which captured the territories and settled them.

That most people associate religious Zionism with the settlements — and not with its real endeavor of becoming Israel’s new political elite — suits the Left. What could be easier than sitting inside the Green Line and blaming the settlers for the occupation? This arrangement has allowed the Israeli Left to duck accountability for its part in Israel’s control over the Palestinians, be it in land expropriation, in killing, and in everything else. And their task has been made easier by the media, which is invariably drawn to the settlements’ most bombastic elements — the hilltop youth, Christians suffering from Jerusalem Syndrome and so on. The idea that we are dealing with radical ideologues absolves the Left of contending with the outcomes of Zionism prior to 1948 or between 1948 and 1967. It also permits the center-Left to portray itself as the “legitimate representative” of the State of Israel, even as its political capital drastically weakens, and all while most of the world boycotts the settlers.

None of this is to say that Tel Aviv and Beit El share the same status — the settlements are a source of violent and continuous friction with the Palestinians, and have engendered legal apartheid in the West Bank. But the residents of Tel Aviv and Beit El bear the same responsibility for the occupation.

With settler dominance in Israel’s government and its institutions now undeniable, old arrangements are falling by the wayside. It is no longer that important to have a left-wing foreign or defense minister who will put on a more acceptable face on the right-wing government. The settlers have taken center stage, and are demanding recognition of their newfound status. The process is almost complete.

The settlers’ new status also brings their leadership’s dilemma into focus: to what extent can they move away from the ideology that propelled them down this path, in the name of preserving the government? This predicament has not yet come to a head, because Israel is not under any real pressure to change the status quo in the territories. It is still possible to settle the land while controlling Israel’s institutions, and that is exactly what the religious Zionists are doing. The question is what will happen once they need to choose one over the other.

What will future Prime Minister Naftali Bennett do in the event that a security or political situation causes his government to collapse, demanding a genuine change on the ground? Religious Zionists are not a majority in Israel, and they depend on the acquiescence of other sectors in Israel — just as Mapai did in its time. When a political earthquake hits, what will Bennett prefer: to allow the Left to return to power and lose the achievements of the last 60 years, or to evacuate the settlements?

This question may sound like science fiction for now, and Prime Minister Bennett would clearly do everything possible to prevent such a situation from arising. But it is highly likely that the day will come when the settlers need to choose between control of the territories and control of the State of Israel. Naturally, neither of these options are particularly exciting for the liberal camp.

_______________________________________________

Noam Sheizaf – I am an independent journalist and editor. I have worked for Tel Aviv’s Ha-ir local paper, for Ynet.co.il and for the Maariv daily, where my last post was deputy editor of the weekend magazine. My work has recently been published in Haaretz, Yedioth Ahronoth, The Nation and other newspapers and magazines.

Noam Sheizaf – I am an independent journalist and editor. I have worked for Tel Aviv’s Ha-ir local paper, for Ynet.co.il and for the Maariv daily, where my last post was deputy editor of the weekend magazine. My work has recently been published in Haaretz, Yedioth Ahronoth, The Nation and other newspapers and magazines.

This piece was also appears in Hebrew on Local Call.

Join the BDS-BOYCOTT, DIVESTMENT, SANCTIONS campaign to protest the Israeli barbaric siege of Gaza, illegal occupation of the Palestine nation’s territory, the apartheid wall, its inhuman and degrading treatment of the Palestinian people, and the more than 7,000 Palestinian men, women, elderly and children arbitrarily locked up in Israeli prisons.

DON’T BUY PRODUCTS WHOSE BARCODE STARTS WITH 729, which indicates that it is produced in Israel. DO YOUR PART! MAKE A DIFFERENCE!

7 2 9: BOYCOTT FOR JUSTICE!

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

PALESTINE - ISRAEL: