Rohingya in India: No Direction Home

ASIA--PACIFIC, ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE, BRICS, 12 Aug 2019

Soumya Shankar – Caravan Magazine [India]

How the world’s largest democracy treats the world’s most persecuted minority.

In November 2016, this madrasa in one of the camps in Narwal, the largest Rohingya settlement in Jammu, caught fire. No one knows the origins of the fire. Most of the houses in the camp were charred, and it was rebuilt from scratch. Hashim Badani

{ONE}

1 Jul 2019 –Fifteen kilometres from the headquarters of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, located in the posh south-Delhi neighbourhood of Vasant Vihar, lie the dusty lanes of the industrial district of Okhla. Near the banks of the Yamuna, the neighbourhood of Madan Khadar houses Muslim migrant communities that provide cheap labour for Okhla’s furniture, sugar and leather factories.

Here, in a neat row of tenements that the locals call Darul Hijrat—abode of the migrant—Mohammad Salimullah’s wife, Fatima Begum, was brewing tea in a five-by-six-foot grocery store. It was December 2017. In the lane outside, the children were concluding their evening games in the mud, singing the popular Rohingya song “Arakan desher Rohingya jaati”—The Rohingya from the country of Arakan.

Salimullah left Myanmar in 2002, fleeing what the United Nations describes as a genocide. His first stop was Cox’s Bazar, the district in Bangladesh that borders the Arakan and today houses the largest refugee camp in the world. Five years later, he pushed further west, into India, drawn by the ideals historically attached to the world’s largest democracy: secularism, peace and prosperity. India, he was sure, would shelter him and his fellow countrymen.

After an itinerant existence spent doing odd jobs in different Indian cities, Salimullah settled in Delhi. Between 2012 and 2017, he started the grocery store, enrolled his three children in government schools and even sent a nephew to university. An uncanny placidity characterised his life in India, a luxury he had not known in Myanmar.

On 9 August 2017, during question hour at the Rajya Sabha, MV Rajeev Gowda, a Congress member from Karnataka, asked whether the home ministry had framed a policy with regard to Rohingya refugees in India, and whether reports stating that the government planned to deport forty thousand Rohingya refugees were true. Kiren Rijiju, then a junior home minister, responded that the Rohingya were “living illegally in the country,” and that the government had “issued detailed instructions for deportation of illegal foreign nationals including Rohingyas,” using its powers under the Foreigners Act, 1946.

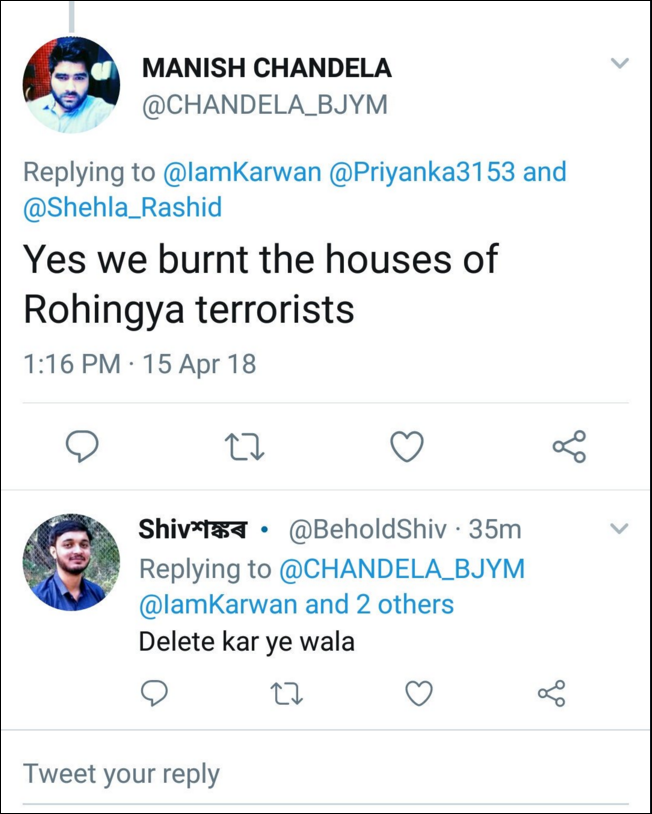

Mysterious fires at Rohingya camps have broken out several times over the past few years. On 15 April 2018, Rohingya shelters in the Darul Hijrat neighbourhood in Okhla were destroyed in a fire. A member of the BJP’s youth wing claimed responsibility in a tweet, but has since deleted his Twitter account. money sharma / afp / getty images

As Rijiju acknowledged in his response to another question asked that day about the government’s Rohingya policy, over sixteen thousand Rohingya had been registered as refugees by the UNHCR. The designation of refugee—which is obtained after a process that can stretch for years, including at least one exhaustive interview at the UNHCR’s Delhi office—is supposed to protect them from “harassment, arbitrary arrests, detention and deportation.”

Rijiju, however, would have none of that. “We can’t stop them from registering” with the UNHCR, he told Reuters a week later. “But we are not signatories to the accord on refugees. As far as we are concerned, they are illegal immigrants. They have no basis to live here. Anyone who is illegal migrant will be deported.”

In the weeks that followed, the lives of the Rohingya refugees living in cramped accommodations—most of them in Delhi, Jammu, Haryana, Rajasthan, Hyderabad and West Bengal—began to change. In Okhla, Salimullah told me, “We feel a difference in the places we go to every day. People look at us differently after the government threatened to deport us.”

Soon after 3 am on 15 April 2018, Salimullah awoke to find that Darul Hijrat was on fire. Fire trucks arrived almost an hour after the fire started, and took four hours to contain the blaze. By dawn, almost all the houses were gutted. Most residents had lost everything they had scrounged together during their peripatetic existence, including the few photographs that remained from their days in Myanmar and the crucial documents that identified them as refugees.

No one was able to ascertain the source of the fire. However, within hours, Manish Chandela, a member of the youth wing of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, tweeted, “Yes we burnt the houses of Rohingya terrorists.” The following day, he again tweeted, “Yes, we did it and we do it again #ROHINGYA QUIT INDIA.” Chandela has since deleted his Twitter account.

As they picked up what remained of their lives, Salimullah and his family began to realise that India had changed. This was no longer the India whose democratic values attracted persecuted peoples from throughout the subcontinent. This was the India of Narendra Modi.

THE WORLD’S LARGEST DEMOCRACY is home to around three hundred thousand refugees from 28 different countries, including stateless people. However, as Rijiju pointed out, India is not a signatory to the UN refugee convention of 1951, or the 1967 additional protocol relating to the status of refugees, and offers no legal protection for refugees. The fate of its refugee communities has historically been determined by the politics of the day.

The Rohingya, described by the UN as the world’s most persecuted minority, have mostly entered India in three waves, each of them in reaction to a ratcheting up of persecution in Myanmar—during the 1970s, in 2012 and in 2017. There has also been a steady trickle between the waves. In 2015, the Rohingya caught the attention of the international media as the ill-fated “boat people,” when several thousands were stranded at sea after repeatedly being denied entry by the governments of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, none of which have signed the refugee convention either.

India’s strategic regional interests have put the Rohingya in an unenviable position, as their persecution continues in the context of geopolitical competition between India and China, both of which want more influence in Myanmar. On 25 August 2017, Rohingya insurgents armed with knives and homemade bombs attacked over thirty police posts in northern Rakhine State. In response, the military and Buddhist mobs burned villages and killed hundreds of Rohingya, leading to over four hundred thousand people fleeing into Bangladesh. Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the UN’s high commissioner for human rights, called the crackdown “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Meanwhile, India’s foreign ministry issued a strongly worded statement promising to stand firmly behind Myanmar in its “fight against terrorism.” The statement said nothing about Myanmar’s history of violence against the Rohingya.

Since coming to power, in 2014, the Modi government has sought to refashion domestic and foreign policy to suit its worldview. Its antagonism towards the Rohingya community is a sign of India’s drift towards Islamophobia, ultra-nationalism and communal disharmony under Modi. Its well-oiled propaganda machinery routinely denigrates the Rohingya as intruders who have no place in the country. This hatred is institutionalised, and given legitimacy by the top leadership. In September 2018 and again in April 2019, Amit Shah, the BJP president and now the home minister, called the Rohingya “termites,” and promised to remove them if the BJP was returned to power, which it did in this year’s general election.

“It is the normal politics of the BJP to spew venom against Muslims,” the lawyer and activist Prashant Bhushan told me. “Here, they are doing three things: calling them Rohingya Muslim instead of refugees, calling them terrorists when there is no proof of this allegation, claiming they have come here to eat into our resources. These three strands of propaganda fit perfectly into the general communal politics of the BJP.” In Modi’s India, the Rohingya face near-complete ghettoisation. Their movement is carefully monitored, and they are not allowed to leave their designated camps. Their conversations with relatives in Bangladesh and Myanmar are under constant surveillance by Indian intelligence.

In Jammu, home to India’s largest concentration of the Rohingya, the community has learnt to maintain a stoic silence in the face of offensive propaganda and mob violence. In the early hours of 3 June this year, nearly a hundred and fifty houses in the Maratha Basti in Jammu, which is home to many Rohingya as well as other migrant labourers, were gutted in a mysterious fire, similar to the one in Okhla. It was the third such fire in the slum in the past three years.

The UNHCR issues identification cards to refugees, but the cards do not make much difference to the Rohingya, since the Indian government does not view them as grounds for legal residency.

Hashim Badani

On 2 September 2017, a group of Rohingya living in the village of Mujedi in Haryana’s Faridabad district were planning to sacrifice two buffalo calves for Eid. They were attacked by a group of locals, who assaulted four men and molested two women before releasing the calves. “They said if we tried to tell the police or complain about what happened to us, they would come and kill us at night,” Mohammad Jamil, who was one of those attacked, told me. A UNHCR representative later helped them file a first-information report, charging “unidentified persons” with voluntarily causing hurt, rioting and other offences. As is increasingly the norm in such cases, nobody was arrested.

Jamil and the 45 Rohingya families living in Mujedi fled to Shahin Bagh in Delhi following the attack. For many of them, who had migrated to Mujedi from Delhi, this marked an ignominious return. Such circuitous migrations are becoming routine. Fearing mass deportation and further attacks, many Rohingya have begun fleeing back into Bangladesh—according to official statistics, over a thousand have done so since the beginning of this year.

Although he admitted the government could not stop the Rohingya from registering with the UNHCR, Rijiju said that since India had not signed the refugee convention, it considered the Rohingya “illegal immigrants” who “have no basis to live here.”

FOR SALIMULLAH, Rijiju’s comment signalled an existential threat for his community. He resolved to fight the policy of mass deportations in court. Represented by Bhushan, Salimullah and Mohammad Shaqir, another Rohingya refugee, filed a petition in the Supreme Court, in August 2017.

Their petition argued that Rijiju’s threat violated the constitutional rights to equality, life and liberty, as well as India’s obligations under international law and treaties. The government had claimed in an affidavit that it was not bound by the principle of non-refoulement—which prohibits states from sending refugees back to where they face oppression—since it had not ratified the refugee convention. The petitioners responded that the principle was enshrined in the international covenant on civil and political rights, the universal declaration of human rights and the 1967 declaration on territorial asylum, all of which India had signed. They noted that the Supreme Court had upheld this principle as part of the right to life, enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. They argued that they were not “claiming the rights of an illegal immigrant to reside in India,” but the application of fundamental rights to all persons, including refugees.

In response to the government’s contention that it had intelligence inputs that the Rohingya have links with terror groups, the petitioners argued that “there is not a single FIR registered against the members of the Rohingya community so far, in any matter that would jeopardise national security.” They quoted the home minister of Jammu and Kashmir, who had told the state’s legislative assembly earlier that year that no Rohingya had been found to be involved in militancy-related incidents.

Unlike the Tibetans or Sri Lankan Tamils or Chin Buddhists from Myanmar, who were all granted asylum by Indian governments in the past, the Rohingya have never been granted refugee status. In 2012, some two thousand Rohingya squatted outside the UNHCR office for a month, asking for recognition as refugees, but their demands were never met. Instead, the government granted a few Rohingya—most of them settled in and around Delhi—long-term visas, ambiguous documents that allow them to stay in the country and enrol their children in government schools. These visas can be revoked, or made redundant, through a change in government policy, much like the one Rijiju was proposing.

The Supreme Court bench hearing the petition has not yet passed a judgement. However, on 4 October 2018, another bench refused to entertain a plea by Bhushan to halt the deportation of seven Rohingya refugees, who had been arrested in Manipur under the Foreigners Act. Human-rights groups have denounced the verdict. “Given the ethnic identity of the men, this is a flagrant denial of their right to protection and could amount to refoulement,” Tendayi Achiume, the UN special rapporteur on racism, said in response. Aakar Patel of Amnesty International’s India branch called the decision “a dark day for human rights in India” and “bereft of empathy.” He added that it “negates India’s proud tradition of providing refuge to those fleeing serious human rights violations.”

{TWO}

TO CONTINUE READING Go to Original – caravanmagazine.in

Tags: Activism, Asia, Asia and the Pacific, Buddhism, Burma/Myanmar, Conflict, Ethnic Cleansing, Genocide, Geopolitics, History, Human Rights, Humanitarianism, Indigenous Rights, Justice, Military, Power, Racism, Religion, Rohingya, Social justice, Solutions, United Nations, Violence, Violent conflict, War

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ASIA--PACIFIC:

- Nepal: Proto-Nationalism Entrapped in the Musical Chair Circle of Political Parties and Floundering Economy

- South Korea's Biosecurity Is Safe, Thanks to Russia

- India and Pakistan: Freedom Lost but Animosity Flourishes

ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE:

- India Must End Arbitrary Arrest, Detention, and Forced Returns of Rohingya Refugees

- Myanmar’s War Has Forced Doctors and Nurses into Prostitution

- Six Years After Their Darkest Hour, the Rohingya Have Been Abandoned

BRICS: