Civil Society Is the Second Pillar of West African Nation States

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 18 May 2020

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. | Virginia Commonwealth University - TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

Experience from many African nations – as well as America, Asia and Europe – provides compelling evidence that civil society plays a fundamental role in social progress and in promoting peace and democratic governance. Civil society has organised democratic governance in West African for millennia, and not simply since colonial rule began. Our political science research shows how civil society has been and remains critical to the evolution of West African Nation States – nearly all of which are recent post-colonial creations – and that a Five Pillar conception of the Nation State conforms more closely to West African realities than the traditional Western concept of Executive + Legislative + Judiciary. We propose that Civil Society and the Military should be added to the traditional State Pillars used in American and European analyses, since both have been – and remain – vital actors in the construction of West African Nation States since the 1960s. Moreover, civil society is often able to exert “countervailing power” – an expression coined by Professor J. K. Galbraith (1952) that puts pressure on the West African Executive, Legislature, Judicial and the Military pillars to help them function more effectively. It is civil society (sometimes with support from the nebulous “international community”) that keeps the other four pillars operating within their appropriate roles. This places civil society in the second place, after the Executive pillar.

Introduction

This paper arises from 30 years of action-research in West Africa, during which the author worked with multiple local and international non-governmental organisations promoting rural and urban development, decentralised democratic governance, and later – in the context of armed rebellion – peace building. Post-colonial rule brought African military dictatorships, most of which have been replaced. In Mali for example, 23 years of military rule ended in 1990-91with a popular revolution that brought democracy. The author was working in Mali at that time, watching civil society emerge from elections in 1992 with political influence, and then play a crucial role in brokering disarmament and permanent peace. Liberia, Sierra Leone, Burkina Faso, Niger, Togo, Ghana, The Gambia and other West African countries (even Nigeria) have seen similar political evolutions; the author has worked as a UN or EU advisor in all of these countries. In recent years, external forces have brought war to the Sahara; but the Peace of Timbuktu negotiated by civil society and celebrated in March 1996 remains a moment of African triumph. The present article provides context for the political, economic and peace successes of civil society in West Africa during the past thirty years.

We start with definitions of traditional and modern civil society in West Africa, and examine how civil society creates opportunities for women to express a voice on political and social issues. Civil society has proved its value in West African conflict mediation (in Liberia1, Sierra Leone2, Mali3 and elsewhere) and is vital for building African social capital, which we explain with examples from Malian society. The economic mirror image of civil society is presented as the Social Economy, of which cooperatives and mutual credit/savings banks are important components. Liberia’s Marketeer cooperatives illustrate most vividly the significance of civil society for women and for the social economy.

The combination of political and economic strength of civil society in West Africa leads us to conclude that a three-pillar Western description of the Nation State is inadequate for Africa: to the Executive, Legislature and Judiciary we need to add Civil Society and the Military. Civil society provides a national source of countervailing power keeping the other pillars in check. Partly this is because West African institutions are weak after decades of military rule. Most States are too small and too poor to fund research institutes or university departments offering alternative policy ideas. UN peace and disarmament negotiations provide examples of how civil society organisations briefed West African governments, supplying research data and analysis to help diplomats develop common regional policies in support of international treaties to reduce land mines and light weapons4 The article concludes that civil society in West Africa has a vital role to play – as the Second Pillar of the State – in the overall strengthening of good governance and the rule of law.

Traditional and Modern Civil Society in West Africa

Civil society is composed of voluntary interest groups that want to get something specific done, “those citizens who form themselves into associations to promote an interest which does not include seeking or exercising political power”(Poulton & Ag Youssouf, 1998, p. 107). The individual is part of society, but does not by himself form part of “civil society”: to do so, he must join an organized group such as cooperatives, associations (including village associations, women’s groups, youth groups, NGOs), mutual insurance, savings or credit groups, social enterprises (such as groupements d’intérêts économiques GIE), trade unions and professional associations, like hunting societies and village councils, football clubs and youth associations, the Red Cross and the Boy Scouts and the Girl Guides.

Some civil society organisations (CSO) have shallow roots, based on a small urban group of elitists or on donor funds – and these are the ones that foreign donors usually see and with whom they have dialogue. But these often foreign-inspired (and often para-governmental) creations are not the most significant parts of civil society. More important are community-based organizations (CBO) with deep roots in their society, especially CBOs with an economic base. There is a rich literature on West African civil society, notably in Nigeria which is so much the largest country of the region. Not wanting to overload our article with references, we can still cite professor Augustine Ikelegbe on the roots of civil society: “Civil society existed in pre-colonial traditional states in Nigeria as associational forms that enabled participation, communication, information flow and influence between the citizens and the state, as well as means of social economic assistance, control of social existence and survival to citizens.” (Ikelegbe, 2013, p. 33) While supporting the value and origins of African civil society, we should not ignore other research (Ikelegbe, 2001) analysing the perversities that modern and even traditional civil society organisations can suffer from government or international interference and influence.

Colonial rule was centralizing in nature (especially in the French colonies), which often diminished the role of traditional civil society, while introducing new models such as trade unions, and farmer cooperatives to promote export crops. There is a creative tension with potential synergy between “modern” civil society (largely, although not entirely, a product of the urban environment) and “traditional” civil society in West Africa (composed of village councils, sororities, hunters’ associations, ecological protection and environmental-management units, age-groups for both men and women which have important functions in education and governance, initiation and mutual self-help). CBOs span both: the modern farmers’ association has roots in the community, even though it exists in response to the mercantile economy; the parent-teacher association may run a modern school, but parents are rooted in their community. In recent years some of the international CSOs have found themselves increasingly in competition with local CSOs. The best international CSOs have understood the need either to develop roots in the African or Asian social economy, or to work with already-rooted CBOs (Poulton et al., 2000).

Countries like Ghana or Nigeria, Mali or Senegal where real areas of political decentralization exist, local Communes (the name may vary in each country) are run by elected officials from “political society”. On the other hand, village councils chaired by the chef de village or village chief can be considered part of “civil society” because the chief’s exercise of administrative power emerges from his or her place in the community and is often a matter of “democratic” selection. Since every head of family and each member of the senior age-group are automatically a part of the Village Council, we may conclude that the chief is really the chairman, and that he exercises social power, rather than political power.

Are church and mosque groups a part of civil society? Maybe. Certainly political parties are not. Political society is separate and different from civil society, because politicians are seeking to exercise power. The same is often true for West African leaders of the imported religions (mainly Islam and Christianity) with their long tradition of exercising spiritual power for political purposes. Priests and Imams certainly influence the way their congregations think and act and spend money. Maybe traditional shamans, gurus, druids and marabouts are a part of the informal social fabric, while formal church and mosque structures should be considered to have established a political forum, creating a separate religious fabric outside civil society. These divisions may be pragmatic rather than rigid, for social boundaries are fluid and they vary from one society to another. Our preference for the “separation of church and state” leads us to keep “civil society” as a secular concept, distinct from political society, religious society and from profit-making private or public companies.

Civil Society Is Important for Expressing the Voice of Women

Women hold a pre-eminent place in West African family and clan structures. The family is the basic unit of traditional West African civil society. In the village and the family, the women are heard loud and clear; yet in the wider political spaces of the modern Nation State, they quickly lose their audience. Women’s ideas are seldom heard as stridently as those of their husbands and brothers in regional and national politics, which occupy new social and political spaces. Changing times require changing habits; Africa and Asia need to create more space for the female voice in socio-political debate.

We may take the Republic Mali as an example of West African political evolution. Gaining independence from France on 22 September 1960, Mali quickly became a One-Party socialist state that was overthrown by military coup d’état in 1968. (Diarrah, 1996). Twenty three years of military dictatorship followed, which brought stability because Mali’s general-president Moussa Traoré was clever enough to jail or kill his various rivals before they killed him. Military stability, however, brought social and economic stagnation (Diarrah, 2000) due both to military corruption, and to the balancing act that almost all West African countries were forced to practise during the Cold War.

Under the Malian dictatorship, all right of association was lost. Meetings of more than six people were illegal, unless they were political meetings to support Moussa Traoré, Cooperatives and farmers’ associations were forbidden, because they threatened an all-dominant military with few ideas, but with guns. Village chiefs had to follow the orders of soldiers and administrators, who kept their jobs only by feeding the army with taxes. The only women’s association allowed to exist was led by Madame Traoré, known as “Madame Ten Percent” because that was her fee for approving donor projects.

The right of association was only regained by Malians after a popular revolution in 1991, which ended 23 years of military rule.5 The country immediately witnessed the emergence of ever-stronger women’s associations, credit unions and Grameen-style savings banks. Numerous women’s CSOs have developed education, health and family planning, and an impressive network of community-owned health centres was started in 1991. The increase of mutualist health centres and savings banks reaching deep into rural communities, has brought great benefits to women and children, in areas where most women never before had health care, nor the opportunity to learn reading or numeracy. On the other hand there seems to be a new poor-gap developing as Africa becomes increasingly urban: the poorest women in the urban slums are seldom able to take part in community associations, especially those supported by donors who deal only with educated association leaders who speak the colonial language (French or English), who can prepare budgets and who know how to talk to bankers and foreigners.

Even under the laws of decentralization, West African countries suffer from a constant vacuum-cleaner effect as bureaucrats in the Capital City (particularly in the finance ministry and in the presidency) hoover up funds and taxes at the expense of rural areas. Organisations such as parent teacher associations, cooperatives, community health clinics and credit/savings banks – which are all a part of civil society – find themselves under constant threat of greater control by ministries. The same centralizing pressure affects forest products and agricultural marketing, areas where African women are major beneficiaries. Civil society is in a constant tension with government officials who feel powerful, or threatened. In Nigeria “governments became suspicious, intolerant and began to infiltrate, politicize, compromise, circumscribe and harass civil society.” (Ikelegbe, 2013, p. 34) This is an experience that many West African civil society leaders will recognize in their own country.

Civil Society, Mediation and African Social Capital6

A West African proverb observes: “The tongue and the teeth are close neighbours working in harmony. Nevertheless, from time to time the teeth bite the tongue.” Occasional conflict, the proverb tells us, is a natural part of human life. When disputes arise in West African society, many mechanisms exist for mediation (Maiga & Diallo, 1998). First are family and village networks. If a dispute goes beyond the village, civil society provides mediators. For example, hunters’ associations are involved when disputes involve boundaries or livestock, or the sharing of forest zones. Pastoral associations and nomadic clan councils become involved when there are disputes over the sharing of water, or to ensure safe access for livestock that need to drink in rivers and lakes, especially when this involves moving cattle herds through cultivated areas.

If disagreements cannot be solved by the protagonists themselves, and especially if violence threatens, then West Africa mobilizes professional mediators, known as griots: these traditional diplomats, historians, praise-singers and negotiators get to work – including women. The word “griot” comes from a Portuguese word for a troubadour, which completely misrepresents the role of griots in African society. The Malenke/Bambara name is “djeli” which equates to “blood” and has nothing to do with singing. Griots are far more important than mere singers, even if they are often poets and musicians: they are “nyamankala” or “people with knowledge” – and thanks to their inherited and ancient knowledge of family history, they are the very lifeblood of social interaction.

If the professional mediators fail, then peace making must rise to the political level involving chiefs, administrative officials like governors, and spiritual leaders. The complete set of networks involved in this process is known in the jargon as “social capital”: the unseen (and definitely non-monetary) glue that binds societies together through mutual respect and mutual exchange, In his book Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela (1994) calls it Ubuntu, or “fellowship” which is Mandela’s South African interpretation of social capital. Unlike financial capital which can be measured in Dollars, Rands or Naira, social capital is an intangible set of values and connections that makes a country, or a community, strong.

Because Mali dominates the Niger River, which has been the centre of West African empires and social structures for millennia, Malian examples are especially useful for explaining the make-up of social capital in Africa. It is helpful to know that the Mali Empire, founded in 1235 by the Emperor Sunjata Keita, the original Lion King, lasted through the Keita and Sonrai dynasties and was larger than the present European Union until it was destroyed by Moroccan invaders at the end of the 1500s (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2020). The Mali Empire covered the lands of nine modern West African states, stretching from the coasts of Senegal into the Sahara Desert of Mali and Niger. The name and symbolism of Mali therefore have significance beyond the current Malian Republic, which still covers more than twice the area of France or Texas.

One special Malian tradition is known in French as “cousinage” – which refers fairly obviously to cousin relationships. In English this is sometimes translated as a “joking relationship” that exists between certain clans and ethnic groups, because humour is a way of diffusing tensions in this part of Africa. West Africans joke as much as the British, and they often laugh at the same ideas. The Malenké/Bambara word is “senenkunnya” describing an ancient tradition that does not easily translate. For the past two or three thousand years, for example, Blacksmiths and Fulani herders have treated each other as “cousins” who may insult each other with impunity, and indeed are expected to do so! The original basis of this relationship was economic interdependency: Fulani cattle herder-warriors crossed the Sahara grasslands 3000 years ago in search of iron, and found Blacksmiths in the Niger Valley who needed milk and meat. A Malian Fulani who is introduced to a stranger with a Blacksmith’s clan name, may look around the room saying: “I do not see any human in this room.” Both will then roar with laughter, and shake hands – whereas such a remark would be insulting to anyone not in a “senenkunnya” relationship. These “cousins” would never intermarry, and they will never fight. In case of a dispute between two Fulani men, anyone from a Blacksmith clan can step between them and the Fulanis will stop fighting. This is a very helpful piece of social capital for West African peace building. Of course, it is useful only if diplomats and politicians make use of it.

Another element of social capital in the lands of the Mali Empire is “jatiguiya” representing a “hospitality” relationship linking families through the generations. It is a mutual honour to receive, and to be lodged: if you accept food from someone in West Africa, it is with the mutual recognition that (s)he could poison you. It therefore it shows trust. If your grandfather was the traditional host of a traveler, then your family will host his grandchildren and they will do the same to yours. There is a Malian proverb that says: “it is better to change towns, than to change lodgers.”

West Africans are great traders. The Soninké, Djoula, Moorish, Tuareg, and Hausa trade cultures enriched the Mali, Sonrai and Sokoto Empires, and brought fame to the southern Sahara trading centres of Timbuktu, Gao, Agadez, Zinder and Kano. The origins of “cousinage” and hospitality lie in the age-old necessity of economic and security interdependency. In the example we cited earlier, bronze-age Fulani herders from the Nile valley were driven out by Hittite warriors wielding iron swords. They migrated westwards to the Niger valley, where they found Blacksmiths forging the metal they needed. Economic exchange was the foundation stone of lasting friendship. It is this fellowship and social capital that makes West African civil society such a rich source of wisdom and peace.

Social Economy in West African Nation States

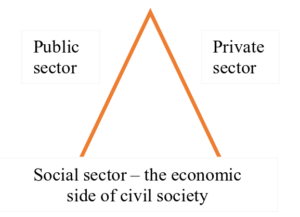

We identify an economy in modern West Africa Nation States composed of three sectors: the public sector, the private sector and the social sector. Their relationship is conveniently represented as a triangle.

Figure 1: The Social Economy Triangle

The social sector is sometimes described as the “third sector” but we prefer the former term, which emphasizes the associative nature of these economic activities and the fact that they offer an opportunity for women to participate (and even to take leadership roles) in the economy. CSOs are often the leading actors in the social sector of the economy: especially CBOs with a productive vocation such as agriculture, artisan production, or savings and credits.

The public sector and the private for-profit sector are notoriously dominated by men. And while extractive and manufacturing industries are economically important in Nigeria, Ghana and Ivory Coast, their economic significance is small in many West African States. In such areas, the social economy is a major source of wealth and employment and also a sector where women can take on the men, and win! When we were designing strategies for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to rebuild the social economy of Liberia after years of vicious civil war, we identified as their key potential partner the Liberian Association of Women Marketeers. In West Africa, women run the markets. While men traditionally grow the staple crops to feed their families (rice, maize, millet, sorghum, peanuts, cassava, yams according to the climate and the soils), it is women who mostly grow vegetables and herbs, keep chickens and produce fresh products that are sold in the daily market place.

In every town in Liberia, there is a market – often a covered market that includes storage and office facilities for the market managers. All of these markets are run by women, and most of the market buildings are actually owned by the local Association of Women Marketeers, which is a nation-wide Liberian civil society organisation. The market managers in each town are elected by the women, each of whom pays an annual membership fee. In addition, each member pays a small daily fee to rent a stall whenever she comes to market to sell her produce. This very democratic association has tens of thousands of members, and plenty of money. Any development initiative in rural Liberia – including rural towns – needs to work with these intelligent, motivated and dynamic women. This Liberian farmers’ movement provides a perfect example of the importance of the West African social economy, and of its potential for promoting economic development, peace and solidarity.

Civil Society Is a Positive Second Pillar of the West African Nation State

Western political theory identifies three pillars of the State: the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary. American scholars add the Press as a ‘fourth estate”7 but this analysis seems inadequate for West Africa, especially where the military has often captured the Executive and with it, control of the Legislature and the Judiciary. How many African (and not only African) States have seen their legislators reduced to a role of rubber-stamping military executive desires? Too many. How many judges are forced to follow political dictates? Too many. For an adequate political analysis framework in Africa, we believe that two more Pillars of the State need to be added: the military, and civil society.

Western academics have a tendency to seek the roots of all modern social phenomena in Europe and in the colonial experience. Back in 1767, the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Ferguson published his Essay on the History of Civil Society combining analysis of the emergence of modern commerce with a critique of society’s neglect of community and civic virtues. This classic of the Scottish and European Enlightenment was the source book for European sociology. But West Africa had a different history and even longer traditions of democratic civil society governance independent of European experience.

West Africa has been governed for thousands of years by village associations, which have always provided an African form of democratic governance. Democracy is not simply the act of voting, as Westerners often seem to think. Indeed elections are easily fixed by those in power. Democracy mainly concerns decision-making. In traditional West African society, every family is represented in the Village Council. Every child – male and female – becomes part of an initiative age-group. Civil society is African, and it is important to recognize civil society as an integral part of the West African Nation State – one of the Five Pillars of the State. After the Executive (led by the President) civil society emerges as the Second Pillar of the State. It is only a strong civil society, acting as a watchdog that has the power to make the other pillars function properly…. including the uniformed forces.

|

Civil society (including inter-faith councils, unions and cooperatives, women’s groups, press associations and the media) has become one of five pillars supporting the modern West African state, alongside the Executive, Legislature, Security Forces and the Judiciary. |

We propose a Five-Pillar theoretical structure for the modern African Nation State:

- The Executive

- Civil Society (including the press)

- The Judiciary

- The Legislature

- The Uniformed and Security Forces

In most African countries, CSOs have shown just how vital they are for maintaining justice and the rule of law. Without the pressure of organized civil society, judges are weak, police are venal and administrators in every service are easily persuaded to follow orders from the governor, sub-governor or other influential officials. There are numerous examples we could cite of judges hesitating to acquit a venal official, only because one or more CSOs intervene as plaintiff or as witness, thereby disturbing the power structure. The presence of the CSO destabilizes the hierarchy, forcing judges, police and administrators to re-assess risk and to consider their own impunity. Each CSO has its own networks, which may have access to other centres of power and influence. By its presence and thanks to its specialist expertise (and also the important people its employees may know), a CSO introduces countervailing powers8 especially in rural areas where local powerbrokers hold great sway. The rule of law is strengthened by the existence of a strong civil society.

Elections are also monitored by civil society, and their comments count. It has been said that the Carter Foundation and OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) sometimes have more influence over election results than a local electorate! (Dodsworth, 2019). Even as this article was being written, the Ghana News Agency on 3rd February 2020 reported an important intervention by the local pro-peace Foundation for Peace & Security in Africa calling for calm and rigour during Ghana’s national election campaign. “We acknowledge that the absence of war does not mean there is no conflict. Conflict will always arise, but how we address it portrays the level of our maturity as individuals and as a nation,” stated FOSDA’s Programme Manager, Theodora Williams-Anti9. The strongest and most independent voices often come from West African women in civil society, who are a force for good governance.

The Legislative branch is also sensitive to CSO pressures. Once the electoral season is passed, parliamentarians often become simply rubber-stamps for decisions of the Executive. CSOs provide an alternative vehicle for democratic representation and expression. Civil society organisations – particularly community-based organisations with real roots in society and not just in the capital city – can sometimes supplant an ineffective Legislature, or exert such local pressure that elected representatives find themselves obliged to heed the views of their electorate instead of simply following the orders of Party Big Men. Where there is no sensible debate in the Legislature, a well-organised civil society has the power to open debates and ask questions of the Executive. Without human rights organisations and strong local governance groups in West Africa, who will curb the abuse of executive power? Where a dictatorship has weakened or removed coherent institutional systems of checks and balances, CSOs often become the principal source of civilian oversight of the armed and security forces and the moral influence that persuades the military to return to their barracks.

In terms of political theory, it is often only civil society that is able to exercise a role of countervailing power against over-centralised political control. Even in countries where democracy functions reasonably well, civil society is important for exploring new ideas and provides a peaceful mechanism for expressing frustrations. A few recent examples of civil society mobilisations that challenge entrenched political power structures include the Yellow Vest protests in France resisting austerity and unemployment; the Occupy “We are the 99%” movement in Wall St attacking the excess of U.S. wealth differentials; anti-globalization demonstrations that have harassed multiple World Trade Organisation and G8 meetings; protests in Hong Kong against centralizing forces from Beijing; and the Extinction Rebellion climate crisis movement. In West Africa, the most important role for CSO mobilisation – even if it seldom generates world headlines controlled by a handful of Western news agencies – is the work that civil society does to protect citizens and limit abuse when a military or other dictatorship reduces to impotence the other Pillars of the State.

Whether in West Africa or elsewhere, international as well as national CSOs have proved to be essential development partners for governments and international organisations. UNHCR and UNICEF contract most of the functional operations in refugee camps to CSOs.10 This mutually beneficial partnership is not going to change any time soon. The political strength of civil society seems to have been enhanced by the use of social media and cell phones. In the 21st century, technology has become a significant “force multiplier” for civil society and we assume that its role will continue to increase in significance.

Civil Society’s Role in Peace and Disarmament: IANSA and WAANSA

CSOs and CBOs can play a significant role in peace building and disarmament, as well as in Security Sector Reform (SSR) and Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration of rebel forces (DDR) – a complex set of processes that we prefer to call 3D4R: disarmament, demobilisation, destruction of weapon stocks, reinsertion, reintegration, rehabilitation, and reconciliation.11 Around the world, most of the “R” functions of 3D4R are actually implemented by CSOs. Because of their close work with communities, CSOs in Asia and in Africa are often more trusted by the people than government officials would ever be. We can cite the case of Cambodia, where the European Union Assistance on Small Arms in Cambodia (EU-ASAC)12 team led by General Henny van der Graaf (and later by David de Beer) worked under the EU flag from 1999-2006, CSOs13 were vital partners in promoting peace, persuading people to surrender their firearms, and creating public awareness about the dangers of small arms and light weapons (SALW), as well as unexploded ordnance (UXO) land mines. 14

When Cambodian weapons were exchanged for community development projects, it was locally-based development CSOs that implemented micro-projects with villagers. Cambodian Human Rights groups provided training for police and local authorities, and helped to rebuild civil-military and civil-police relations strained by 30 years of banditry and civil war. Unlike West Africa, Cambodian society has no tradition of CBOs; but the pagoda – a peaceful institution led by monks and elders – provided the civil society space where villagers could leave their weapons anonymously, for later collection and destruction by the authorities. By the time the EU-ASAC had finished six years of security sector reform and disarmament, almost 200,000 weapons had been destroyed by the Royal Cambodian Government. None of that could have been achieved without partner CSOs (EU-ASAC, 2006).

The role of CSOs in African peace processes has been greater still. The Mali peace process of 1992-1996 was the product of civil society, working in partnership with the nation’s new democratic leadership. Mali’s first elected head of state, Dr Alpha Oumar Konaré was himself a leader of civil society (he had been successively a leader of the teachers’ union, mutualist health clinics, and the publishing cooperative Jamana).

The 1996 Peace of Timbuktu was negotiated by the combination of traditional and modern civil society (Lode & Ag Youssouf, 2000; Poulton & Ag Youssouf, 1998).15 The Government made space for community leaders to lead reconciliation meetings uniting all the people who used a common economic and ecological space. Women’s associations played an important role in bringing together economic leaders and armed groups, and in persuading young men (their sons, brothers, husbands) to join the 1995 cantonment process and surrender their weapons. Later the same would be true in Liberia, where the Women-in-White and other CSOs became a vital part of the peace process, persuading (even “forcing”) the rebel leaders to agree peace terms. In 2011, two Liberian women, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Laymee Gbowee, would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (Cooper, 2017).

In negotiating the 1996 Peace of Timbuktu, the concept of “space” was defined by Malians in terms of economic value, and not in terms of artificial administrative or political borders. Every part of civil society was represented in the negotiations. Men with weapons were not the main leaders of the negotiation process: unlike Mali today, where government leaders, MINUSMA (Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations Unies pour la stabilisation au Mali) and Opération Barkhane (the French-led anti-terrorist military operation) have allowed the so-called peace negotiations to drag on between men with guns who represent only themselves. During the 1990s a truly West African peace mechanism was developed, based on civil society and stimulated by CSOs (both local and international) that provided stimulus and encouragement, communications and very small amounts of funding. The Malian peace machinery worked successfully and the United Nations helped by adding occasional drops of diplomatic oil (and modest amounts of money) into the peace machinery in order to help it turn more smoothly at certain key points.

The two successful turn-of-the-century peace-and-disarmament experiences in Cambodia and in Mali came together beautifully in 2001 at the first United Nations conference on small arms and light weapons (SALW). SALW are truly weapons of mass destruction that kill thousands of victims every year. Together with Costa Rica, Norway and the Netherlands, Cambodia and Mali became the lead countries promoting the 2001 “Programme of Action to prevent, combat and eradicate the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects” (PoA) that was adopted by consensus on 20 July 2001. The PoA makes reference to the 2001 Firearms Protocol to the UN Convention on Transnational Organised Crime. Its implementation has led to the negotiation of other agreements both at the regional and global level, such as the 2005 International Tracing Instrument.

Few countries in West Africa, or indeed across the world, have the resources in their foreign ministries to research such a minor-yet-complex issue as small arms and light weapons, let alone to develop policy papers for their governments. This work was done for them by International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA), the International Action Network on Small Arms, an international non-governmental and civil society organisation (NGO/CSO) that coordinates a global movement against gun violence. Hundreds of organisations on five continents are working to stop the proliferation and misuse of small arms and light weapons (IANSA, 2020). IANSA’s regional group in West Africa is WAANSA16 with local member organisations in all West African States; and similar structures exist for the Americas, Europe, Middle East, Asia and the Pacific. In every African country, local IANSA members were able to provide their governments with expertise, position papers and regional coordination concerning SALW and the future treaty negotiations. One of the areas in which African nations are weakest, is in research capacity. Universities are understaffed and under-equipped, while very few independent research institutes exist. IANSA’s member groups have been able to fill this space for peace and disarmament issues. For a derisory sum of around $2 million per year, IANSA supplied precious research and lobbying services (which included pushing Legislatures and patiently educating elected officials and parliamentary commissions to ratify the treaties). IANSA’s influence across a decade of SALW negotiations and peace treaties, included support for the earlier Mine Ban Treaty that served as a model for the PoA. Without civil society, neither treaty might have been signed or reached ratification. In many ways, the PoA precursor was the Mine Treaty of 1997, another civil society success story.

The “Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction” was adopted in 1997 and it entered into force on 1 March 1999. Often called the Ottawa Convention, it has now been ratified by 164 States and it was largely the product of international civil society building on the SALW movement. The Nobel Peace Prize Committee recognized this in 1997 by awarding the prize to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines and to its organiser Jody Williams “for their work for the banning and clearing of anti-personnel mines.” Other international CSO Nobel Peace Laureates have included Amnesty International (1977); the International Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs (1995), Doctors Without Borders (1999); International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (2017). The International Committee of the Red Cross has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize three times (1917, 1944, 1963)17. These international civil society institutions all work with local national chapters, achieving fine results across a world of turbulence.

Conclusion: Civil Society Strengthens Good Governance

We have cited a number of examples drawn mainly from West Africa, to show how civil society organisations (CSO) can influence the Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers, as well as the international community. CSOs make the three traditional Pillars work more effectively. In certain circumstances such as negotiating the 1996 Peace of Timbuktu and ending the Liberian civil war, CSOs (including women’s associations) exerted enormous pressure on rebel groups as well as on the uniformed forces, bringing army and police back in line to fill their designated role in the West African Nation State. When a strong civil society is not functioning to curb military ambitions and to strengthen the institutions of good governance, it becomes easier for a threat of military takeover to become reality.

We are not arguing for the replacement of the State by non-State actors. The role of CSOs is not to replace the other Pillars of the State, but to push them to perform the functions for which they have been designed. The State cannot do everything. The natural partners of State institutions for grassroots development and good governance, are local civil society and community-based organisations …. Not simply local government officials. The closer we can bring governance decisions to the community, the more successful we shall be in promoting community decision-making, peace and reconciliation, sustainable development and good governance – reducing poverty and out-migration as a result. Without CSOs and especially the mobilisation of women, good governance and sustainable development cannot be achieved.

Civil servants are not natural supporters of civil society. Diplomats feel comfortable talking to each other. Bureaucrats do not like a multitude of dissident voices. They often see CSOs as pressure groups led by troublemakers who threaten the power of authority (the power of bureaucrats). We say, “Good for the troublemakers!” We believe that you cannot have too many associations and interest groups. Clubs and charities enrich a country. CSOs are organisations that provide ordinary citizens with a way to participate in the daily life of a nation. Politicians and civil servants may well become confused by multiple voices, and therefore dislike a disorganised civil society. They are wrong! Democratic debate is intended to be messy. You can have too many soldiers and too many civil servants, or too many foreigners and too many locusts, but you cannot have too many associations and CBOs all trying get people involved, seeking to make things better and to get things done.

We have emphasised the important role played by civil society and the social economy in giving a voice to women. Not just a voice: CSOs create spaces where women are allowed to take decisions, and these decisions improve their incomes, their social and family status, and their ability to protect themselves and their daughters. While national political spaces have been difficult for women to access, largely because education systems and laws are controlled by those who have mastery of the colonial language, West African women have huge influence in the family and in the village community. Throughout West Africa, in families and associations, women are described by their men as ‘my minister of finance’. It is widely accepted that women are more honest, more efficient, more committed to the group and to their children, less egotistical than their husbands, and less inclined to kleptomania. The best person to be the treasurer of an African organisation, is a woman. In such a culture, it seems clear that women should be used where they are most respected. The mobilisation of women into positions of responsibility will lead to better governance throughout the society.

Every society is different. Political systems evolve their own characters and we are not suggesting that one rule will fit every case. Cambodia is not Liberia is not Nigeria is not Mali. Throughout West Africa, however, civil society was the principal democratic governance mechanism until the colonial period. Half a century later, after decolonization and then demilitarization, civil society has once again become a fundamental pillar of the modern West African State. We argue that civil society is the de facto Second Pillar of the African State, working alongside the Executive to promote good governance by ensuring that the legislative, judicial and uniformed pillars work more efficiently.

Notes:

1 The Women-In-Peace Network (WIPNET) in Liberia, known as the “Women-in-White” was instrumental in creating the Liberian peace settlement. The story of their achievements is told in a remarkable documentary film Pray the Devil Back to Hell directed by Gini Reticker and produced by Abigail Disney. The film premiered at the 2008 Tribeca Film Festival, where it won the award for Best Documentary.

2 See articles written by civil society leaders in Sierra Leone covering multiple aspects of peace building and disarmament, in Ayissi & Poulton (2006).

3 Lode & Ag Youssouf (2000).

4 For example in 1998 the sixteen ECOWAS member countries signed a regional Moratorium on Small Arms and Light Weapons, brokered by the United Nations with strong civil society support coordinated by UNIDIR (United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research). This Moratorium provided huge impetus for the 2001 UN meeting in New York that adopted the “Programme of Action to prevent, combat and eradicate the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects” (PoA) in July 2001. This West African process is described in Poulton & Ag Youssouf, La Paix de Tombouctou (1999), which also presents in annex the French text of the signed Moratorium.

5 The history of modern Mali and its rulers can be summarised as follows:

1880-1960 centralised repressive colonial and military French rule.

1960-1968 post-Independence one-party centralisation under Modibo Keita.

1968-1978 military dictatorship under Moussa Traore and a junta of colonels.

1979-1991 centralised one-party repression under general Moussa Traore.

1991-1992 transition to democracy under Amadou Toumani Touré.

1992-2002 election in 1992 of Mali’s first democratically elected President, Dr Alpha Oumar Konaré, who attempts to install participatory decentralisation.

1999-2002 Decentralisation is put in place with elected Mayors in 701 Communes.

2002-2006 Amadou Toumani Touré elected President; begins re-centralisation.

2006-2012 Amadou Toumani Touré re-elected, then ousted in a March coup d’état.

2012-2013 Captain (later general) Amadou Haya Sangaré’s military junta, under international pressure, is replaced by interim President Dioncouda Traoré.

2013-present Ibrahim Boubacar Keita elected President.

6 West African social capital is described in Poulton & Ag Youssouf, A Peace of Timbuktu, p15-21; more detailed theoretical analysis can be found at the website https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/social-capital-theory

7 See for example Schultz, Julianne (1998, p. 49). The expression “fourth estate” was originally used in 1787 by Edmund Burke during a speech in the British Parliament. According to Thomas Carlyle’s book On Heroes and Hero Worship: “Burke said there were Three Estates in Parliament; but, in the Reporters’ Gallery yonder, there sat a Fourth Estate more important by far than them all.”

8 Coined in 1952 by John Kenneth Galbraith of Harvard University, the term Countervailing Power or countervailence described diffuse market forces opposing monopolies. The concept has probably gained more relevance in political theory, when analysing institutionalized mechanisms that wield power. When one power centre appears to gain excessive or overwhelming force, other centres of power or influence may coalesce to create counter-forces that limit abuse of power. Thus in our discussion, an overweening Executive may find itself constrained by the objections of religious leaders, or by legislative, judicial or other forces including civil society (trade unions, agricultural unions, student unions, women’s associations and other groupings of citizens) opposing specific abuses of power. Or the military may take over, claiming that an abusive Executive has lost its legitimacy.

9 https://ghananewsagency.org/politics/fosda-urges-ec-stakeholders-to-put-ghana-first-163437

10 The role of CSOs in refugee resettlement and rehabilitation is discussed in Poulton & Tonegetti (2016) p 276; and by Walet Halatine, Zakiyatou in the same book p. 178.

11 See the discussion document “Lessons Learned about DDR by the people of EPES Mandala Consulting” consulted 27 January 2020 on the website: http://www.epesmandala.com/img/pdf/DDR_EPES_Mandala_FINAL_Fall2008.pdfhttp://www.epesmandala.com/img/pdf/DDR_EPES_Mandala_FINAL_Fall2008.pdf

12 European Union assistance for curbing small arms and light weapons in Cambodia, a disarmament and peace building project that lasted from 1999 until 2006.

13 Local Cambodian CSOs were involved in confidence-building and education programmes, notably the Working Group for Weapons Reduction (WGWR) supported by Oxfam, International Red Cross, War-on-Want and other international non-governmental organisations and later supported by JSAC (Japan Assistance Team for Small Arms Management in Cambodia) and JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency); while EU-ASAC development projects in exchange for weapon-collection were implemented by the local branches of Partners For Development, Helen Keller International, and by a UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) project working with the Cambodian Ministry for Rural Development. WGWR was the principal Cambodian organisation working with IANSA, the International Action Network on Small Arms and Light Weapons.

14 See https://www.eu-asac.org/

15 Poulton & Ag Youssouf, (1998) A Peace of Timbuktu, p109-115; Lode & Ag Youssouf (2000).

16 WAANSA = West African Action Network on Small Arms and Light Weapons, a coalition of civil society organisations and IANSA’s West African network, also has a French acronym RASALAO = Réseau d’action sur les armes légères en Afrique de l’Ouest. Its headquarters is in Accra

17 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-nobel-peace-prizes

References:

Ayissi, A., & Poulton, R. E. (Eds.). (2006). Bound to cooperate – Conflict, peace and people in Sierra Leone. Case studies in peace building and disarmament written by leaders of civil society in Sierra Leone (2nd ed.). UNIDIR. https://unidir.org/publication/bound-cooperate-conflict-peace-and-people-sierra-leone

Carlyle, T. (1841). On heroes and hero worship. James Fraser.

Cooper, H. (2017). Madame President: The extraordinary journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Simon & Schuster.

Diarrah, C. O. (1996). Le Mali de Modibo Keita. Préface de Christian Coulon Collection: Points de vue concrets Afrique subsaharienne Mali – Actualité Sociale et Politique. L’Harmattan.

Diarrah, C. O. (2000). Mali: Bilan d’une Gestion Désastreuse. L’Harmattan.

Dodsworth, S. (2019). Double standards: The verdicts of western election observers in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization, 26(3), 382-400. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1534099

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2020, January 15). Songhai empire, Africa. https://www.britannica.com/place/Songhai-empire

EPES Mandala. (2011). Lessons learned about DDR by the people of EPES Mandala Consulting. EPES Mandala Consulting Ltd. http://www.epesmandala.com/img/pdf/DDR_EPES_Mandala_FINAL_Fall2008.pdfhttp://www.epesmandala.com/img/pdf/DDR_EPES_Mandala_FINAL_Fall2008.pdf

European Union Assistance on Small Arms in Cambodia. (2006). EU ASAC 2000 – 2006. https://www.eu-asac.org/

Ferguson, A. (1767). Essay on the history of civil society. Edinburgh University Press.

Galbraith, J. K. (1952). American capitalism: The concept of countervailing power. Houghton Miffin.

Ikelegbe, A. E. (2001). The perverse manifestation of civil society: Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Modern African Studies, 39, 1-34.

Ikelegbe, A. E. (2013). State, civil society and sustainable development in Nigeria (Monograph Series No. 7). Centre for Population and Environmental Development.

International Action Network on Small Arms. (2020). www.iansa.org

Lode, K., & Ag Youssouf, I. (2000). Programme de rencontres intercommunautaires – Contribution à la bonne gouvernance – Rapport de synthèse. Commissariat au Nord (Présidence de la République).

Maiga, I., & Diallo, G. (1998). Problématique des Conflits Liés à la Gestion et à l’Accès aux Ressources Naturelles: Cas de Nioro du Sahel, Nara et Mopti. Programme GRAD/IIED/JAM Sahel.

Mandela, N. (1994). Long walk to freedom. Little Brown & Co.

Poulton, R. E., & Ag Youssouf, I. (1998). A peace of Timbuktu: Democratic governance, development and African peacemaking. United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research.

Poulton, R. E., & Ag Youssouf, Ibrahim. (1999). La Paix de Tombouctou: Gouvernance démocratique, développement et la paix africaine, avec une préface de Kofi Annan (2nd ed.). United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research.

Poulton, R. E., & Tonegutti, R. G. (2016). The limits of democracy and the postcolonial nation state: Mali’s democratic experiment falters, while jihad and terrorism grow in the Sahara. Mellen Press.

Poulton, R. E., Ag Youssouf, I., & Baby, M. (2000). Peacemaking and sustainable human development – Big pictures or small projects. In A. Krishna, C. Wiesen, G. Prewitt, & B. Sobhan (Eds.), Changing policy and practice from below: Community experiences in poverty reduction (pp. 36-45). United Nations Development Programme.

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the fourth estate. Cambridge University Press.

Walet Halatine, Z. (2016). A refugee woman’s perspective. In R. E. Poulton & R. G. Tonegutti (Eds.), The limits of democracy and the postcolonial nation state (pp. 178-181). Mellen Press.

__________________________________

Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science Research, Feb 2020, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1-14

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment and the Founder of the EPES Mandala Peace Consultancy. He is a sometime faculty member of the European Peace University (Austria) and an Affiliate Research Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, and is a consultant advisor on Africa to governments, the U.N. and the European Union. He is a specialist in terrorism, disarmament, conflict transformation, and peace building. He has 25 years of field experience with UNDP, EU, USAID and NGOs. He is the author of several books in French and English on development and disarmament. He received his Ph.D. from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, France. repoulton@epesmandala.com – poultonrobin@gmail.com

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment and the Founder of the EPES Mandala Peace Consultancy. He is a sometime faculty member of the European Peace University (Austria) and an Affiliate Research Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, and is a consultant advisor on Africa to governments, the U.N. and the European Union. He is a specialist in terrorism, disarmament, conflict transformation, and peace building. He has 25 years of field experience with UNDP, EU, USAID and NGOs. He is the author of several books in French and English on development and disarmament. He received his Ph.D. from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, France. repoulton@epesmandala.com – poultonrobin@gmail.com

Tags: Africa, Civil society, Research, Social sciences, Social structures, West Africa

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 18 May 2020.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Civil Society Is the Second Pillar of West African Nation States, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: