Weaving Pain in Silence: Gender Based Violence (GBV)

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 10 Aug 2020

Irene Dawa – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Lives of Refugee Women in Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement, Arua, Uganda

Introduction

Conflict and wars always impact men and women in different ways, but possibly never more so than in contemporary conflicts[1]. While women remain a minority of combatants and perpetrators of war, they increasingly suffer the greatest harm[2]. In contemporary conflict, as much as 90% of causalities are among the civilians, most of whom are women and children[3]. For most women, the end of war and conflict is marked by the excessive effects of trauma and shame as a result of Gender Based Violence (GBV)[4]. Women in refugee settlements often face specific and devastating forms of sexual violence, and other forms of violence which sometimes result from their vulnerabilities from war. This article presents the finding of a study undertaken in Rhino Camp refugee settlement in Arua, Uganda. It details the GBV experiences of refugees, contributing factors as well as its effects on survivors. It concludes by giving conflict sensitive recommendations to implementing partners.

However, it is important to understand violence and how it manifests. Violence coined by Galtung in 1960’s” is any physical, emotional, verbal, institutional, structural or spiritual behaviour, attitude, policy or condition that diminishes, dominates or destroys others and us[5]. Those, words, attitudes, structures or systems that cause physical, psychological, social or environmental damage and/or prevent people from reaching their full human potential Galtung.[6] In this sense, Galtung’s theory recognises violence at different levels as direct, structural and cultural. This definition gives necessary parameters within which we can understand violence, how it is deeply structured into the system of relationships, within socio-economic and political arrangements including in refugee settings. Therefore, systemic violence can in turn be a root causes of conflict, as well a behavioural response to a specific conflict situation.

Refugee settlements are characterised by conflicts as a result of lack of basic needs, unequal power relations, breakdown of institutions of social control and order. This leads to exposure to the dangers of group violence as a result of low capacity of protection agencies both local and international, and the host governments. This setting breads a fertile ground for GBV to become a common phenomenon and takes different forms like rape, female genital mutilation, physical, psychological and emotional abuse, defilement and bride kidnapping in the name of ‘early marriage’ and sexual harassment among others.

GBV continues to permeate Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement, despite all the efforts that government of Uganda and partners have put in. Social norms on which violence against women and children is anchored run deep and cannot be eliminated overnight by even the best laws and policies. Harmful culture and traditions mean that women suffer in silence. This means that without continuous self-assessment and empowerment and overtly seeking out the views of women and children who are in most cases voiceless, we risk ending up with a response that leaves out the most vulnerable.

Using qualitative study, the article attempts to highlight the current forms of GBV in the settlement, factors exacerbating it and the challenges faced by survivors. The data were collected through individual interviews, focus group discussions, semi- structured questionnaires, and reports from implementing partners. Research addressing GBV are very sensitive because of the implication it can have on participants. For this reason, necessary permission was sought before data collection could commence, this included permission from Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) and settlement leadership, district officials United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Participants gave Verbal consent because it was not possible to obtain written consent due to the high illiteracy levels among the study sample. Participants were informed of the study purpose and importance of confidentiality was emphasized. For safety reasons, respondents’ names are not recorded.

Findings of the study suggest that there is an increase in GBV in Rhino camp refugee settlement. Common cases included: Rape/attempted rape, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, domestic violence: intimate Partner or other family members, harmful cultural practices: forced marriages and girls not allowed to go to school because of gender role expectations in the family (housekeeping, cooking, care of children). Further, the study found that GBV is under reported. This was attributed to lack of knowledge on reporting procedures and fear of stigmatisation. Lack of justice was mentioned. Participants hesitate to report such crimes, since perpetrators are usually released on bond. The implementing partners blamed South Sudanese local leaders for taking the laws into their hands in a bid to addressing such issues that are beyond their jurisdiction. Lastly, there is lack of trained health care workers who are unable to fill the incident reporting forms including consent for release of information, monthly statistical forms, and a client feedback form. The study therefore concludes that government and its implementing partners should take appropriate measures to address these GBV in the settlement through training of healthcare workers, security forces, local leaders on reporting and documenting GBV cases. Focusing on community based approached is therefore recommended to build the capacity of local leader to respond to GBV in the settlement.

The prevalence of GBV- General overview

GBV and especially Sexual violence (SV) and intimate partner violence (IPV) affect people around the world, causing immense harm, suffering, loss of dignity, and immediate and long-lasting medical and psychological consequences. Globally, 1 in 14 (7.2%) women report having experienced sexual violence by a non- partner in their lifetime and almost 1 in 3 (30%) women have experienced physical and/ or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime[7]. Refugees are often at heightened risk of GBV during emergencies. This can be due to several factors, including the sudden breakdown of family and community structures after forced displacement. Certain groups in a population may be particularly at risk of GBV: older persons, persons with disabilities, adolescent girls, children, LGBTI persons, and female heads of household.

GBV may be perpetrated by anyone, including individuals from host communities, refugee or IDP communities, and humanitarian actors. Persons in positions of authority (police, security officials, community leaders, teachers, employers, landlords, humanitarian workers) may abuse their power and commit sexual violence against persons of concern. Changed social and gender roles or responsibilities, as well as the stresses of displacement, can cause or even exacerbate tensions within homes, sometimes resulting into domestic violence. During situations of armed conflict, sexual violence may be used as a weapon of war.

Violence against women violates many fundamental rights protected by international human rights instruments, including the right to life, right not to be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, protected by international conventions. To respond to GBV and protect women, Uganda has over the years committed to promoting gender equality, role of women in development and address issues of Violence Against Women, Girls and Children (VAW/VAC). The country has various good frameworks including the Uganda 1995 Constitution, the Vision 2014; The National Development Plan II; Uganda Gender policy (2007), The Domestic Violence Act (2010); The Prohibition of FGM Act (2010); The Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act (2009), The Penal Code Act (Amended 2007); The Local Government Act, among others. Institutions such as Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development, Equal Opportunities Commission; National Planning Authority; other government institutions and CSOs have also promoted gender equality and economic empowerment of women. These institutions have made efforts to address issues of Violence Against Women and Girls, Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights. Globally, this call is embedded in the 2030 Agenda for sustainable Development and other frameworks that emphasize the achievement of gender equality and women empowerment.

Key terminologies

A Refugee: A person who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country, this can be due the fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.[8]

Gender-based Violence: is an umbrella term for any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed gender differences between males and females including acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.[9]

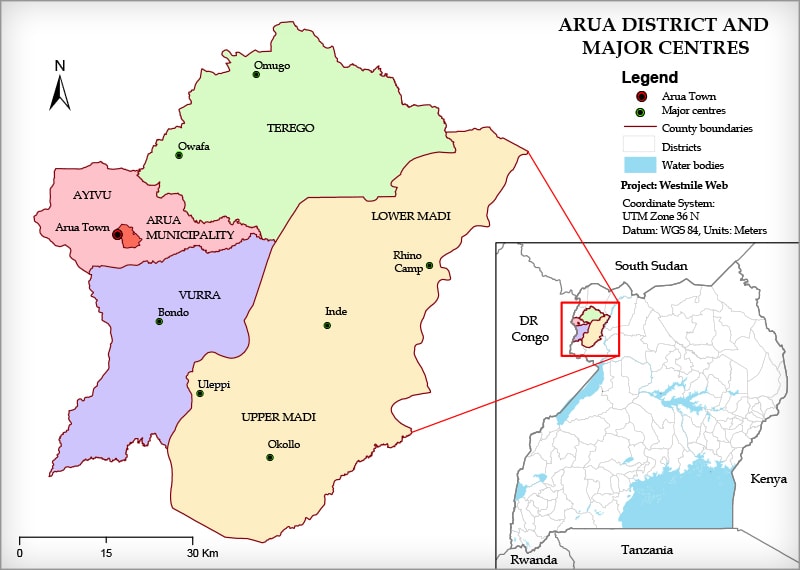

Study Context -Arua District

Arua district is in West Nile Region of Uganda. It is bordered by the districts of Maracha to the North West; Yumbe to the North East Nebbi to the South; Gulu to the East and bordered by Democratic republic of Congo (DRC) to the West. The district comprises mainly of rolling plains rising from the Nile floor in the rift valley. Arua is strategically located as a hub connecting other districts of West Nile. The economy of Arua depends mainly on agriculture which employs over 87.7% of the households. Of those employed in agriculture, 86.2% are engaged in the crop sector, 0.6% in Animal rearing, 0.9% in fishing.[10] According to the 2014 census only 3.6% of the households earned their livelihoods from formal employment. The remaining proportion of the households of approximately1.8% are engaged in cottage industry and yet a smaller portion depends on family support and other miscellaneous activities. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics figures, the district had a total population of 782,077 in 2014 of which 52.1% are female.

The map of Arua District where Rhino Camp settlement is located.[11]

Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement

Rhino Camp settlement, originally opened in 1980, in the wake of the South Sudanese civil war to host the sudden influx of refugees into northern Uganda. The settlement currently has a population of 104,912 and 28,350 households, out of this, 104,839 are refugees, women and children account for most of the population 87,533 (83%) (53,845 women 51%). The refugees are mostly from South Sudan 102,355, followed by DRC 1,739, Sudan 724, Rwanda 47 and Burundi 17[12] The settlement had Rhino camp and Impevi but due to increased refugee influx from South Sudan, in 2017, the settlement was expanded with the establishment of the Omugo zone . The settlement has seven zones which includes, Ofua, Omugo, Ocea, Odobu, Siripi, Tika and Eden Zone.

GBV in the settlement

GBV is a common phenomenon in the settlement. Unfortunately, there is a scanty data on it. There are a few reports published by UNHCR. For example, the last comprehensive report indicated that 3,643 (3097F/546M) SGBV incidents reported between January and September 2019 in the refugee hosting communities. According to local government official in Urema Sub- County, this figure from UNCHR doesn’t reflect the reality of daily cases of GBV in the settlement (Interview 3rd March 2020). The scanty data is attributed to the lack of reporting of cases of GBV by survivors and community especially among the South Sudanese refugees.

Existing GBV cases in Rhino Camp settlement

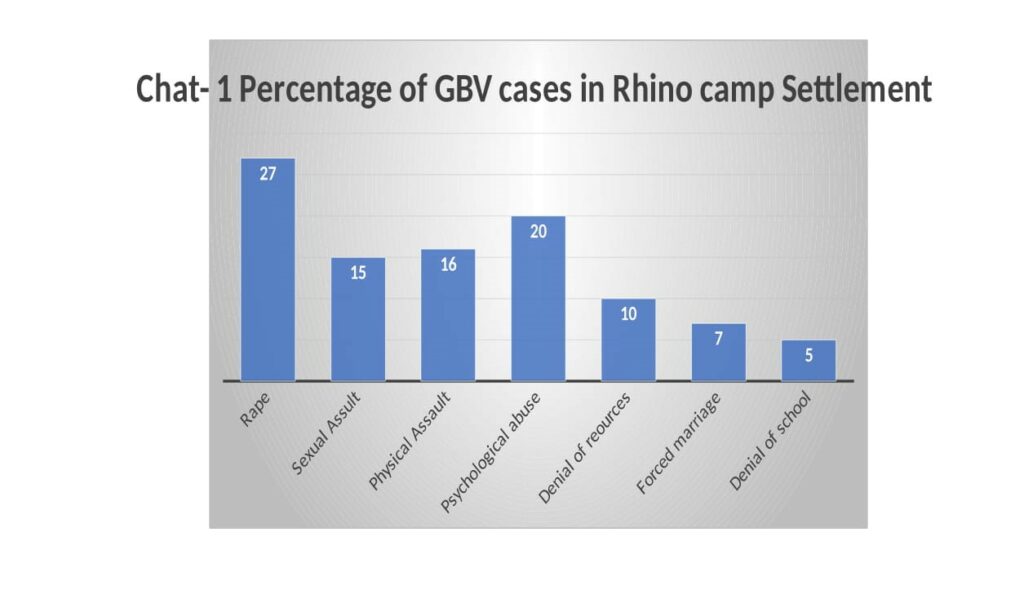

They study revealed that GBV is more prevalent among South Sudanese refugees 65% reported cases in 2019[13]. According to OPM and UNHCR, this cloud be attributed to the cultural norms and practices among South Sudanese refugees. The common GBV cases that were reported during the study included Rape, Sexual Assault, Physical Assault, Psychological / Emotional abuse, Denial of resources, Forced/ Early Marriage and denial of school for girl child. See the graph below for more details in %.

From the graph, we can see rape is the widespread with 27%, denial of school is lowest at 5%. This are risk factors exposing the refugees to rape cases that need to be addressed. The study did not seek to understand where these rapes takes place, but it was reported thar women get raped by their husbands, girls get rapped on their way from school and while looking for water and firewood. The low percentage of denial of education could be attributed to emphasis put on girl child education by the Ugandan government and implementing partners. A staff of Windle Trust the partner leading education intervention reported that those parents who stop their girl’s child to go to school face penalties. There is a strict rule on schools to follow children who do not report to school (Interview Windle trust 10 March 2020).

From the graph, we can see rape is the widespread with 27%, denial of school is lowest at 5%. This are risk factors exposing the refugees to rape cases that need to be addressed. The study did not seek to understand where these rapes takes place, but it was reported thar women get raped by their husbands, girls get rapped on their way from school and while looking for water and firewood. The low percentage of denial of education could be attributed to emphasis put on girl child education by the Ugandan government and implementing partners. A staff of Windle Trust the partner leading education intervention reported that those parents who stop their girl’s child to go to school face penalties. There is a strict rule on schools to follow children who do not report to school (Interview Windle trust 10 March 2020).

Contributing factors to GBV in Rhino Camp Settlement

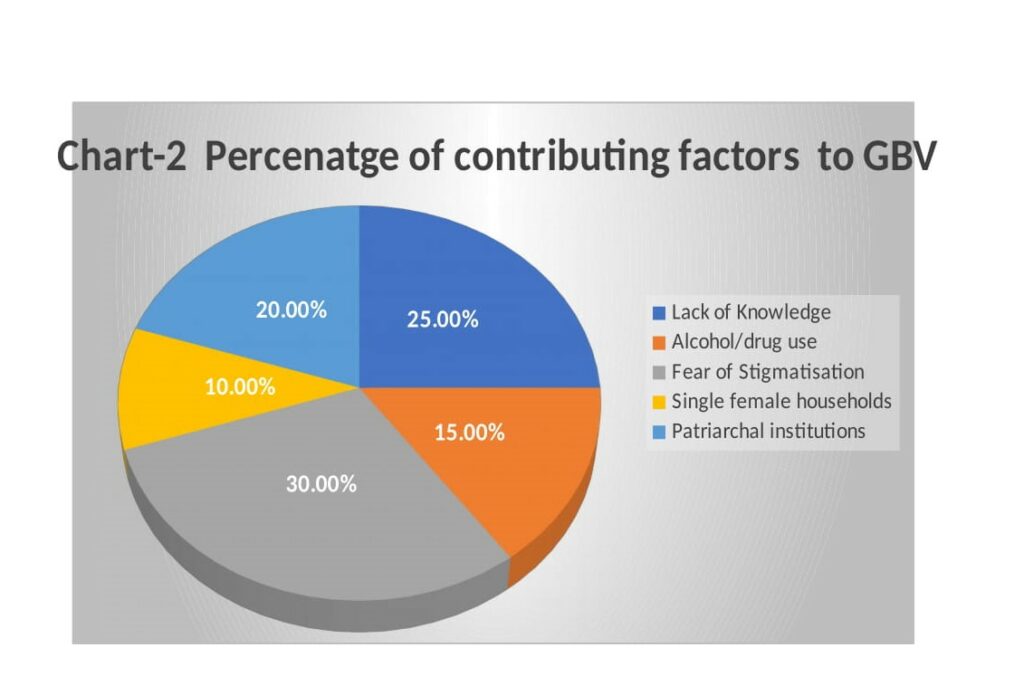

- Despite the above statistics, the data collected showed that the lack of data because of none compliance to reporting by the refugees one a major factor. When cases are not reported, this is no true reflection of the reality and this makes interventions difficult as it may not address the real issues.

- The lack of knowledge on GBV and its effects on survivors among the population. It was noted that for South Sudanese, violence that occurs within the family is often perceived to be a ‘private’ affair, meaning that the police, local leaders, neighbours, and other entities are not able to intervene unless a report is taken them. This means that domestic violence or even rape by close relatives in the settlement are not report most times because they are criminal cases.

- Alcohol/drug use, this is attributed to the trauma of war. It was found that many refugees depend on alcohol to forget the past and in the processes, some become aggressive and commit such crimes under the influence of drugs. Many are reported to have committed suicide after drinking.

- Single female households, many homes in the settlement are headed my females, as the data indicates that 81% of the population are women and children., in an indicator that women are forced to do everything they can do look for survival. War draws women into poverty as a result of low levels of employment, women refugees get exposed to the risk of SV and related sexual transmitted diseases.[14] This is also because of Male and/or society attitudes of being disrespectful to females single or women living without male partner.

- Men dominant the community/settlement leadership, usually. For example, the refugee welfare committee (RWCS) is full of males. RWCS is a political position, so one must campaign for it, making women reluctant part to participate. Women also reported that their husbands deter them from participating in such politics. This leaves them with less freedom of bringing up sticky matters. They fear the consequences, since personnel handling GBV cases are at community levels.

- Fear of being stigmatised and being persuaded by family members not to report GBV cases was another factor. This means that perpetrators are not held accountable and are often left at large – something encouraging the practices.

From the chart, stigmatisation seems to be a big issue among the refugees. This was attributed to the fear of been rejected by parents and fear of being forces to marry the rapist, a practice that is very common in South Sudan. Lack of knowledge on GBV is a big challenge, too, contributing to stigmatisation. To address this, national and regional legal frameworks should be used to educate the population. For example, on the universal declaration of human rights especially Article 16. (1) which states:

“Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution. (2) Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses. (3) The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State”[15]

This clause gives survivors and community basic information associated with their rights and will create a sense of security while dealing with reporting cases

- Inadequate resources such as food, fuel, water, etc., make women more vulnerable and at greater risk of sexual exploitation or other forms of GBV. Few water sources contribute to long waiting times to access water. These have left so many women in danger. They have to walk for long distances looking for water and firewood. For example, a woman was reported to have had mis-courage at water point after waiting in the hot sun for six hours.

Challenges faced by survivors of GBV in the settlement

- The legal process of getting justice is a challenge as perpetrators are released on bond, this makes communities to lose hope in the case and fear justice will not be done this in turn contributes to the low level of case reporting by survivors

- Few health facilities mean survivors often have to walk long distances to reach health facilities, which puts them at a greater disadvantage to accessing health care. For those who access the health centres, they report that services are hindered by limited staffing, inadequate medicines, and lack of emergency medical support. This makes survivors to be reluctant or go late for check-up and this destroys evidence for health workers to give specific recommendations. This situation is worsened by the fact that there no partner for psychosocial support leading to increase of suicidal cases

Way forward to partners

- Institutions which receive complaints and reports of GBV (community leaders and the law enforcement officers) must be properly, extensively and repeatedly trained covering wide range of issues on GBV by the UNHCR, ICR and OPM.

- Handling of complaints and offences effectively must become part of the evaluation process for local leaders. This can be done through facilitation and availing the local leaders with the necessary logistics to enhance and further motivate them execute their duties in their respective areas by relevant organisations. Facilitation can be through provision of bicycles to ease transport, stationary, pamphlets and brochures on GBV should be provided to LCs RWCs, Women Leaders, police, health personnel etc.

- Counselling services be strengthened to victims and their family members. Counselling services should be carried out at individual, family, and community level. Family and community counselling will improve acceptability and integration of victims within their respective families and societies.

- Health units play key roles in health emergency management; thus, their operations should be strengthened by recruiting more qualified staff, (IRC, MSF and MOH) and available personnel be trained in emergency care of GBV cases and on recording cases.

- Girls are the most vulnerable group of GBV, owing to their development needs as well as their health, educational, and socio-economic needs. Therefore, they should be specifically targeted for assistance. Assistance should be channelled to their families, schools towards their health, social needs and welfare. For example, they should be assisted to attend school by giving scholastic materials, Menstrual pads etc for them to stay at school, while those out of school be given vocational training.

Coordination and accountability

There should be periodic coordination between agencies working on GBV to review, (assess, monitor, evaluate and follow up on the handling of reported cases of SGBV. All agencies should be involved: e.g.: paralegals trained by the concerned and medical personnel, schools and appropriate community representatives.

Community sensitization and participation:

- A committee that’s concerned with issues of GBV in each village should be formed. This will make the process and procedures more understandable and help to ensure that all are trained and receive training updates. It also increases perceived credibility and makes reporting and follows up easier.

- It is recommended that GBV awareness activities become integrated into the health, educational and community service programs in the host sub- counties. The Sub-Counties and the district should therefore develop appropriate policies to mainstream GBV related activities into the District plan of activities.

NOTES:

[1] Khuloud, Alsaba and Anuj Kapilashrami (2016) Understanding women’s experience of violence and the political economy of genderinconflict: thecase of Syria. Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 24, No. 47, Violence: a barrier to sexual and reproductive health and rights p. 5-17. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/26495886.(Accessed on 0 May 2020).

[2] The African Union (2018) AU strategy for gender equality and women empowerment 2018-2028. Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36897-doc-52569_au_report_eng_web.pdf (Accessed on 3 April 2020).

[3] World Bank (2016) CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE IN THE 21ST CENTURY CURRENT TRENDS AS OBSERVED IN EMPIRICAL RESEARCH AND STATISTICs, P.8. Available at https://www.un.org/pga/70/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2016/01/Conflict-and-violence-in-the-21st-century-Current-trends-as-observed-in-empirical-research-and-statistics-Mr.-Alexandre-Marc-Chief-Specialist-Fragility-Conflict-and-Violence-World-Bank-Group.pdf Accessed 2 April 2020).

[4] Maina Grace (2012) ‘An Overview of the Situation of Women in Conflict and Post-Conflict Africa’: a conference paper, Issues 1 2012. Available at https://www.accord.org.za/publication/overview-situation-women-conflict-post-conflict-africa/ (Accessed 10 April 2020).

[5] Galtung, Johan (1969)’Violence, peace and peace research’: Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1969), P. 167-191, Sage Publications, Ltd. Stable. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/422690. (Accessed 15 April 2020).

[6] Ibid

[7] WHO (2013) ‘Global and regional estimates of violence against women’: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7BD64E3FE30CAE290F7C66B49454DD8C?sequence=1 (Accessed 6 March 2020).

[8] UNHCR (n.d) ‘who is refugee?’ Available at https://www.unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html (accessed 13 April 2020).

[9] IASC (2015) ‘Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action’: Reducing risk, promoting resilience and aiding recovery. Avialble at www.gbvguidelines.org (Accessed 5 March 2020).

[10] West Nile web (2019) ‘Facts and figures- Arua district.’ Available at https://www.westnileweb.com/districts/arua-district (Accessed on 04 April 2020).

[11] Ibid

[12] UNHCR (2019) ‘Uganda – Refugee Statistics (April 2019) Rhino settlement. Available at https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/uga. (Accessed 7 April 2020).

[13] CEPAD (2019) ‘Internal survey report on GBV cases in Rhino Camp settlement. Unpublished report

[14] Mediel Hove1 and Enock Ndawana (2017) ‘Women’s Rights in Jeopardy’: The Case of War-Torn South Sudan Sage publications, P.1-13.

[15] UN (2008) ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’: Dignity and justice for all of us. UN Library, p.6.

__________________________________________________

Irene Dawa is a Ph.D. candidate in Peace Studies at Durban University of Technology, South Africa. She holds an MA in Peace and Conflict Studies from the European Peace University in Austria and another in International Relations and Economics from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, Italy. Her research focuses on: gender-based violence in armed conflicts; women, peace and security in Africa; and good governance. She is a specialist of GBV in emergencies, women empowerment conflict analysis, conflict sensitive programming, peacebuilding, protection and program development. Over the past 10 years, Irene has worked in 15 different countries around the world. Iryndahda@gmail.com

Irene Dawa is a Ph.D. candidate in Peace Studies at Durban University of Technology, South Africa. She holds an MA in Peace and Conflict Studies from the European Peace University in Austria and another in International Relations and Economics from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, Italy. Her research focuses on: gender-based violence in armed conflicts; women, peace and security in Africa; and good governance. She is a specialist of GBV in emergencies, women empowerment conflict analysis, conflict sensitive programming, peacebuilding, protection and program development. Over the past 10 years, Irene has worked in 15 different countries around the world. Iryndahda@gmail.com

Tags: Africa, Conflict Analysis, Direct violence, Gender Based Violence-GBV, Research, Structural violence, Violent conflict, War, Warfare

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 10 Aug 2020.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Weaving Pain in Silence: Gender Based Violence (GBV), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: