The Trump Pardons and Fast-Tracking Capital Punishment

ANGLO AMERICA, 11 Jan 2021

Richard Falk | Global Justice in the 21st Century – TRANSCEND Media Service

Measuring the Man: Pardons and Capital Punishment

31 Dec 2020 – Among the disquieting dimensions of this strangest of all Christmas holidays has been the lurid spectacle of misplaced empathy by Donald Trump, placating cronies and criminals who helped him circumvent law and morality while exhibiting hard heartedness toward those unfortunate souls awaiting execution on death row in federal prisons. Perhaps, most lamentable of all oversights has been the failure up to this moment to pardon Assange on both principled and humanitarian grounds. The U.S. application for Assange’s extradition, if granted, could subject him to a lengthy prison term.

The pardon power is set forth in general terms in Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution, and by Supreme Court decision is without limitation beyond its own terms. The pardon power applies only to federal crimes, and cannot be used to pardon state crimes, and it does not apply to impeachment proceedings. The rationale for the pardoning power, contested at the time by federalist opponents of strong national government, was set forth in Federalist Paper #74 authored by Alexander Hamilton. The stress was on the need for some check on mistaken or unjust punishments resulting from improper applications of federal criminal law. In Hamilton’s words, without “easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel.” This linkage between the pardoning power and the need for an effective antidote for the unjust application of criminal law was central, and has generally governed its use, but there have been a variety of questionable pardons in the last 50 years, but none to match the Trump’s undisguised corruption of pardoning as an aspect of governance.

Eyebrows have been raised in the past when occasionally U.S. presidents have pardoned former contributors to their political campaigns or tried to avoid criminal accountability for those who tried to cover up presidential wrongdoing. Richard Nixon explored all his options in seeking to achieve impunity for those who carried out the Watergate break-in and his closest complicit aides. Nixon, apparently wary of partisan pardoning, even floated the idea among his aides of freeing the Watergate band of warriors from criminal accountability at the same time that he uncharacteristically pardoned an equivalent number of anti-war Vietnam protesters or issuing a pardon for all who left the country to evade military service during the Vietnam War. Nixon’s idea, never acted upon, seemed to assume that a show of political balance would quiet criticism of an inappropriate pardon. Obviously, such wheeling and dealing is not what the drafters of the Constitution had in mind. Gerald Ford, as president, issued a controversial pardon to Nixon in 1974 for all offenses against U.S. law committed during his time in the White House (1969-1974), understood to refer to the Watergate break in, and part of the arrangement to secure Nixon’s resignation.

Now Trump comes along with a more coherent message of loyalty to followers and those beloved by the extreme right-wing and vindictiveness toward those who fall afoul of law and order militants. Love for those who stood by him, however disreputable their behavior or how gross their flaunting of the law, which even concluded in several instances consorting with America’s number one geopolitical rival, Russia. While so bestowing pardons as if thank you notes for evil deeds, Trump indulged his seemingly gratuitous hatred toward those who were sitting on death row in Federal prisons sentenced to death, including in some cases where the evidence establishing guilt was flimsy or still under legal challenge, and often where the harshness of the sentence seemed to reflect considerations of race and class more than the gravity of the crime. Trump abandoned the practice of civility by past presidents, who suspended federal executions during the transition period between elections and inauguration. Instead Trump went to the perverse opposite extreme by ordering the fast-tracking of executions, presumably to take away the possibility of commuted sentences or eventual pardons. Any reliance on capital punishment is increasingly rejected by societies where democratic values and practices prevail, and it remains a substantive and symbolic concern for all of us who fear and oppose the violence of the state whether at home or abroad. No state is trustworthy enough, or even sufficiently competent, as to be empowered with the right to impose a death sentence even on those convicted of transgressing the criminal constraints of law in the most horrifying ways. It is not only a matter of being sure not to execute someone later shown to be innocent or of executing a convicted person who was subjected to a harsher punishment than the crime warranted. The rejection of capital punishment is an expression of a societal commitment to the sacredness of every human life, whatever the offending behavior, expressing the view that a path to redemption should never be altogether closed off.

Unquestionably, the worst of Trump’s pardons involved Blackwater security guards who opened fire back in 2007 on unarmed Iraqi civilians in Nisour Square in Baghdad , killing 14 Iraqis including children aged 9 and 11, and wounding another 30. This event was viewed by the Iraqi population as a massacre of such gravity that it generated demands for legal redress from this people supposedly ‘liberated’ from the oppressive and dictatorial rule of Saddam Hussein in 2003, and if not met, then to the steeper demand that the U.S. end its occupation and remove its troops and bases. Four of the Blackwater killers were indicted, and in 2014, three were convicted of ‘voluntary manslaughter’ and one of ‘murder,’ and all were given lengthy prison sentences. Trump’s pardons, apparently partly prompted by right-wing extremist agitation in ultra-conservative U.S circles, caused ripples of disapproval by the liberal media in America, but expressions of outrage and dismay in Iraq, especially by families of those killed or wounded. It reinforced an image of the occupation of Iraq as an imperialist venture, which devalued the lives of Iraqis, and completely discredited American claims of promoting the rule of law and a claimed commitment to criminal responsibility for its civilian security operatives. A widely quoted observation by a classmate of one of the young victims in 2007 expresses the toxic perception of the pardon by the Iraqi people, including anti-Saddam Iraqis who had initially welcomed the American intervention, although later living to regret their receptivity to a foreign regime-changing intervention: “The Americans have never approached us Iraqis as equals. As far as they are concerned, our blood is cheaper than water and our demands for justice and accountability are merely a nuisance.”

Of course, the pardon exposes the larger unindicted international crime of aggression against Iraq in 2003 followed by occupation, which with troublesome irony, was less supported back then by Trump than by the incoming president, Joe Biden. At the time of the Nisour Square Massacre there were over 160,000 American mercenaries in Iraq, a for-profit supplement to a troop presence of about the same number, a telltale expression of mercenary militarism disconnected from securing the homeland. As with other large-scale U.S. regime-changing interventions, the costs in Iraq have been incredibly high, and yet none of the promised positive results prompting the attack in 2003 have been achieved. Iraq became the site of one those ‘forever wars’ that causes the population to suffer for long periods, usually ending only when the imperial invader gets tired, and gives up the venture.

In Vietnam this intervention fatigue happened with memorable clarity, in Afghanistan periodic efforts to negotiate a settlement with the Taliban point in the same direction. In Iraq, ISIS emerged in reaction to pro-Shi’ite occupation policies and sectarianism greatly intensified as a result of the American occupation. A national circumstance of bitterness, chaos, and unresolved political strife, is the legacy of 17 years of costly occupation that also diminished the overall U.S. reputation as a generally benevolent global actor entrusted with a leadership role. The pardons certify this underlying geopolitical refusal of the American ‘bipartisan consensus’ to live with the results of national self-determination in the post-colonial, post-Cold War era, where nationalist resistance to intervention is more intense and the ethos of exploitative occupation becomes manageable only by dehumanizing the indigenous population through intimidating violence and a regime of inequality that corrupts elites while making most citizens endangered strangers in their own homeland. The Palestinian ordeal is a gruesome variant, colonists displacing natives from which many forms of malevolence follow, including cycles of resistance inducing displacement and oppression. The Zionist Project of establishing a Jewish state in an essentially non-Jewish society almost inevitably led to racially tinged modes of oppressive internal security, which is best understood as a form of apartheid that the statute of the International Criminal Court has classified under the heading of Crimes Against Humanity in Article 7.

The Blackwater pardons occur just a short time before Iranians and others in the region pause to remember General Qassim Soleimani on the first anniversary of his drone assassination on the direct order of the U.S. President, not only an extreme example of targeted killing in the vicinity of the Baghdad Airport that violates international human rights law has been described by the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions, Agnés Challimard, in her 2020 official report as amounting to an ‘act of war’ in violation of the UN Charter and customary international law. As Iranians and Iraqis have been quick to observe, the Soleimani assassination and the Blackwater pardon are two sides of the same coin, the geopolitical currencies of U.S. criminality abroad and impunity at home. As has been pointed out in an article on the blowback potential of the Blackwater pardons, the anger aroused among those in Iraq and elsewhere opposed to the American presence in the Middle East could retaliate in ways that put at greater risk the lives of American soldiers. [See Iveta Cherneva, “Soleimani’s Death Anniversary could Fuel Retaliation by pro-Iran Militias,” Modern Diplomacy, Dec. 30, 2020].

Nothing better reveals the Trump approach than the vindictive pursuit of Julian Assange despite his serious illness and prolonged confinement, the Obama period decision to not pursue prosecution despite an espionage indictment for revealing classified information, and in light of the essential nature of his whistleblowing undertaking that focused on the disclosure of war crimes in the Wikileaks’ documents. Although the Federal Court in Virginia that found him guilty of 17 violations of the 1917 Espionage Law, subjecting Assange to a potential 175 years in a maximum security prison, likely coupled to the added punishment of solitary confinement, it was the first time ever that a journalist doing his job was prosecuted and convicted of espionage. The United States has requested the UK to extradite Assange, with a decision due from the London Central Criminal Court on January 4th of 2021, which seemed hostile to AAsssange in its administration of the extradition hearing, with the presiding judge reported to have close family ties to leading figures in British intelligence. Acts deemed ‘political crimes’ are excluded from extradition, and Assange’s behavior was totally politically motivated. As such, Assange’s supposed ‘criminal’ offenses should certainly be treated as non-extraditable, and on humanitarian grounds he should be released from Belmarsh Prison in London. Assange, along with others who dared to reveal the hidden infrastructures of state crime, deserve statues in public squares, not prison cells.

This notorious effort to criminalize the disclosure of state crimes strikes one more blow against truth-telling and the limiting of freedom of expression in countries that pride themselves by proclaiming democratic values. The scandalous abuse of Assange accentuates prior efforts to criminalize the whistleblowing exploits of Daniel Ellsberg, Edward Snowden, and Chelsea Manning. It is more evident than ever thar the future of constitutional democracy depends on the safety valve of an unintimidated media and the insulation of informants from criminal liability. This is not to deny the existence of tricky policy issues associated with protecting legitimate state secrets relating to homeland security, diplomacy, and law enforcement.

There have been rumors that Trump might still use his authority to grant Assange a pardon, not so much for political reasons, as to avoid one more line of controversy. After all, it was Trump during the 2016 presidential campaign who encouraged WikiLeaks to release a batch of emails thought to be damaging to his opponent, Hillary Clinton. There are others in the Trump entourage, most prominently Mike Pompeo, who support extradition and jail because the Assange disclosures allegedly weakened U.S. security. Whatever Trump does about Assange, it will not greatly alter this final chapter of his presidency, which exposes above all else, his warped attitudes toward life and death.

If there is no pardon, Biden’s handling of this now incendiary pardon/impunity/capital punishment interface in relation to Julian Assange will give a strong clue to the kind of leadership he will provide. Unfortunately, Biden is on record as having compared WikiLeaks to a terrorist organization. No matter what happens on January 4th, drama will ensue.

There are lessons to be learned and acted upon by progressives in reaction to these dual celebrations of death at this time of seasonal holiday at the end of a year of this strange year dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic: demilitarize security at home and abroad, disarm America and Americans, retrain and restrain the police, abolish capital punishment, close hundreds of American overseas bases, bring the navy back to territorial waters, demilitarize and denuclearize as national priorities, rejoin and enhance global cooperation related to climate change, and shift resources from ‘national (regime) security’ to ‘human (people) security.’

__________________________________________

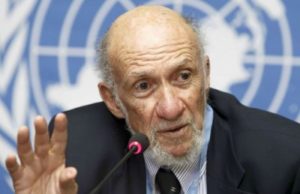

Richard Falk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network, an international relations scholar, professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, Distinguished Research Fellow, Orfalea Center of Global Studies, UCSB, author, co-author or editor of 60 books, and a speaker and activist on world affairs. In 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) appointed Falk to two three-year terms as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on “the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.” Since 2002 he has lived in Santa Barbara, California, and associated with the local campus of the University of California, and for several years chaired the Board of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. His most recent book is On Nuclear Weapons, Denuclearization, Demilitarization, and Disarmament (2019).

Richard Falk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network, an international relations scholar, professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, Distinguished Research Fellow, Orfalea Center of Global Studies, UCSB, author, co-author or editor of 60 books, and a speaker and activist on world affairs. In 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) appointed Falk to two three-year terms as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on “the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.” Since 2002 he has lived in Santa Barbara, California, and associated with the local campus of the University of California, and for several years chaired the Board of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. His most recent book is On Nuclear Weapons, Denuclearization, Demilitarization, and Disarmament (2019).

Go to Original – richardfalk.org

Tags: Anglo America, Assange, Corruption, Death Penalty, Justice, Trump, USA

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.