Covid 19 Pandemic: Body Disposal Crisis–What to Do with Dead People in a Living World? (Part 2)

COVID19 - CORONAVIRUS, 31 May 2021

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

(Read Part 1 HERE)

Towards an Eternal Presence

25 May 2021 – Death and dying, as well as mechanism of body disposal have been a challenge for humanoids since genesis of man, as related in the scriptures of Abrahamic faiths[1]. The Biblical murder of Abel by Caine[2] posed a challenge for his brother as to how to dispose the body of his murdered brother. Abel was the second son of Adam and Eve, who was killed by his brother Caine, becoming the first record of murder. Not knowing what to do, he saw a bird digging into the sand and that gave Caine an idea that he should bury the body into the ground[3]. He subsequently proceeded to dig a hole in the soil and bury the corpse, firstly to hide his dastardly act and secondly to dispose of the body. This became the standard of care practice for the dead in a living world. Over the millennia, as humanoid evolved physically, from the primitive Neanderthal man[4], the social understanding of the ethics of managing a dead body became highly refined, with often highly complex funereal rites customs, traditions and ethic of a procedural protocol to subject the dead to after the soul has left the physical body. It is stated that “how a nation or community treats its dead, reflects the level of social evolution of that group of people”.

The number of global deaths from the Corona virus pandemic tallies at 3,469,640 with a total infection, clocking at 167,116,334 as on 25th May 2021, 5:21 AM, according to John Hopkins Resource Centre[5] statistics. The author has discussed the burial, land shortages, as well as the scarcity of wood for open funeral pyres in India, necessitating river funerals and disposal of the corpse in the holy Ganges River[6] compounding to the existing challenge of pollution.

The funereal customs following the demise of a humanoid are largely prescribed by religion and the culture of a particular community, in terms of how to dispose of a body or cadaver and what are the associated procedural aspects of the demise.

When death is eventually encountered, people, all around the world, deal with death and treat the bodies of their beloved, differently. Funeral rites vary between cultures, but the major factor which plays a role in how the final rites and funerary processes are performed, together with the disposal of the human body, is religion.

There are numerous ways in which a dead body is handled by living people and since most of humanity subscribes to the belief of life after death, funereal customs are specifically undertaken to make the life of the deceased in the hereafter as comfortable as possible. This resurrection after death is not only subscribed to by the followers of the Abrahamic faiths but was also the overarching religious philosophy of pharaonic Egypt where the journey in the underworld was as equally important at the physical life and provisions were made to ensure that process is subscribed to fully by the Pharaohs’ priests and household.

The dead body of the Pharaoh and other high caste individuals were mummified, by a complex process which often lasted 90 days in preparation for eternal immortality in the underworld. A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions[7]. Mummy is also the term given to a body embalmed, naturally preserved, or treated for burial with preservatives after the manner of the ancient Egyptians. The process varied from age to age in Egypt, but it always involved removing the internal organs (though in a late period they were replaced after treatment), treating the body with resin, and wrapping it in linen bandages. Among the many other peoples who practiced mummification were the people living along the Torres Strait, between Papua New Guinea and Australia, and the Incas of South America. There was a widespread belief that Egyptian mummies were prepared with bitumen.

Mummies were not only prepared by the Egyptians. They were also done in feudal China.[8] Mummification in Korea and China, the South East Asian Mummies prepared during the Mawangdui, Song, Ming and Joseon Dynasties. Over the decades, mummy studies have expanded to reconstruct a multifaceted knowledge about the ancient populations’ living conditions, pathologies, and possible cause of death in different spatiotemporal contexts. Mainly due to linguistic barriers, however, the international knowledge of East Asian mummies has remained a mystery, until recently. Upon analysis the outcomes of the studies so far performed in Korea and China in order to provide mummy experts with little-known data on East Asian mummies. The report, illustrates the similarities and differences in the mummification processes and funerary rituals in Korea and China are highlighted. Although the historical periods, the region of excavation, and the structures of the graves differ, the cultural aspects, the mechanisms of mummification, and biological evidence appear to be essentially similar to each other. Independently from the way they are called locally, the Korean and Chinese mummies belong to the same group with a shared cultural background.

The dead do speak and mummies speak up, as well. Through a comprehensive and holistic approach to the civilisations of the past, scholars have traced the biological and sociocultural profiles of ancient populations. Over the decades, the living conditions, pathologies, and possible cause of death of ancient populations in different spatiotemporal contexts (i.e., ancient Egyptians mummies, bog bodies, the Similaun Man (Oetzi), crypt mummies, the Arctic and high-altitude permafrost mummies, and South American precontact mummies) were progressively reconstructed by mummy studies[9]. Scientifically, the reality of the academic tradition of mummy studies in East Asia is distinct from other continents. East Asian mummies are culturally and biomedically so unique that extensive dissemination of cutting-edge research is paramount. Using modern scientific techniques and apparati such as scanning, the prevalence of diseases, including parasitic infestation in the people of that era, in the region during ancient times has been elucidated. In Korean mummy research, radiology showed to be a highly efficient diagnostic tool[10] that enabled researchers to establish the state of preservation of the inner organs and to estimate the patient’s pathological conditions in a non-invasive way.

However, the radiological approach also has its own biases. Since mummified tissues and organs underwent taphonomic[11] changes over the centuries, it may be difficult to apply modern radiological knowledge to ancient bodies. To overcome these biases (pathology versus pseudopathology), post factum dissections were performed to confirm the actual pattern of the mummified organs previously observed by computed axial tomography[12].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) was also applied on a hydrated Korean mummy, providing researchers with invaluable information on the state of preservation of the organs with minimal damages[13]. Lastly, endoscopy showed that the organs of the Korean mummies displayed a “vivid” appearance[14] were sceptical about the real efficiency of this minimally invasive technique applied to the study of ancient bodies.

Mummies have been a valuable source of information on the diseases that plagued the ancient Korean people. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was confirmed in a 17th century, Korean mummy by anatomical [15]and paleogenetic techniques[16]. Kim et al.[17] identified calcified pulmonary nodules in a 350-year-old-Joseon mummified individual, thus providing scholars with the oldest evidence of ancient pulmonary tuberculosis in South Korea. Thanks to multiple biomedical techniques, congenital diaphragmatic hernia[18] and Cherubism[19] were also diagnosed in Korean mummies. Research on ancient parasites was very successful field of investigation.

Since the first paleoparasitological report performed on a child mummy[20], remarkable evidence of ancient parasitism was accumulated through multiple studies. Using light and electron microscopy, Shin et al.[21] showed an excellent state of preservation of ancient parasite eggs in coprolites[22]. The paleoparasitological studies were conducted on coprolites from 24 Korean mummies, allowing the parasite infection prevalence of 16th to 18th century Joseon people[23] to be estimated. The prevalence of soil-transmitted parasites among these Joseon mummies was estimated to be 58.3 % for Ascariasis. and 83.3 % for Trichuris species.

This prevalence is quite similar to the one described in the 1971 Korean National Survey. The infection rate of soil-transmitted parasites dropped with the rapid industrialisation during the 1980s’[24]. More specifically, concerning the Trematode[25] species, the Joseon mummies showed very high infection rates (25 % for Clonorchis; 33.3 % for Paragonimus) whereas only 4.6 % (Clonorchis) and 0.09 % (Paragonimus) infection rates were detected in the 1971 National Survey[26]. Tis implies that the Trematode infection rates had already decreased way before the beginning of modernization in South Korea whereas the changing pattern of the infection rates of soil-transmitted parasites in South Korea occurred around the time of modernization [26].

Cases of parasitism rarely seen among clinical patients were reported in the Korean mummies. Ectopic (hepatic) paragonimiasis was identified in a 17th century Korean mummy[27]. A liver mass just underneath the diaphragm was identified through CT scanning; a subsequent microscopic examination revealed the presence of multiple ancient Paragonimus species eggs inside the mass. This was the first archaeo-parasitological case of liver abscess caused by ectopic paragonimiasis. Another case of ectopic paragonimiasis was also observed in 400-year-old Korean, female mummy[28]. In this case, Paragonimus eggs were detected in lung, faeces, intestine, and liver samples, but not in the brain, nor in pelvic-cavity-debris. The repeated reports of ectopic paragonimiasis indicate that the disease was widespread in the Korean people during the Joseon period[29].

Another tomb in South Korea called Mawangdui (Mawangtui) grave, provided scholars with an exceptional finding. In 1971, during the construction of an air-raid shelter, a grave of the Western Han period was discovered at a depth of circa 20 meters. The archaeologists, who successfully excavated the tomb in a period of political constraints, found multiple coffins (two outer and four inner coffins) of different sizes fitted within one another. Upon opening the innermost coffin, the archaeologist discovered the ‘cadaver’ of a woman that did not show evidence of decomposition[30]. According to archaeologists, at the time of discovery, the mummy was flooding in a liquid that filled the coffin.

The lady’s name was confirmed to be Xin Zhui, the wife of Li Cang (or Li Tsang), Marquis of Dai (or Tai) during the Western Han Period. Even after two thousand years, the mummified lady and her tomb assemblage were amazingly well preserved. Research performed on the tomb assemblage found in the Mawangdui grave provided scholars with valuable information about the life of this ancient Chinese lady[31]. The Mawangdui mummy underwent thorough biomedical investigations[32]. The body of the lady, who was 154 cm tall, weighted 34.3 kg. Her blood type was A. Her skin and hair were intact, soft tissues had maintained the original elasticity, and the joints could be moved freely. X-rays showed that the skeleton was complete.

At autopsy, it was shown that although the inner organs were remarkably shrunken, their relative positions had remained unaltered. Histology showed that both peripheral nerves and skeletal muscles were well preserved[33]. Many signs of ancient diseases were identified in the Mawangdui lady[34]: atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, cholelithiasis, chronic lead and mercury poisoning, fracture and malunion of the distal end of the right ulna and radius. Based on the pathological evidence, it was hypothesised that the most likely cause of death was a myocardial infarction or an arrhythmia due to heart attack possibly consequent to a biliary colic[35]. Muskmelon seeds (n=138.5) were found inside her intestines and paleoparasitology showed that she had suffered from Schistosoma japonicum, T. trichiura, and Enterobius vermicularis[36]. All these studies provided scholars with unexpected information about the life of a 2,000-year-old Chinese woman. The mummy is currently displayed in Hunan Museum, along with other artefacts.

The question which is raised is why did the Korean mummies spontaneously preserve and what kind of mummification allowed the Korean mummies to preserve? Climate in Korea is not suitable for natural mummification and, before the 20th century, the Joseon did not resort to embalming techniques[37]. Cultural beliefs implied that the intact preservation of the ancestors’ corpses was an ominous sign for the descendants.

In this regard, the discovery of a series of perfectly preserved mummified bodies became a sensational topic in South Korea. The mummification process was unlikely to be caused solely by natural or artificial causes, but is more likely the result of multiple, complex and synergistic mechanisms. Korean researchers interested in the actual mechanism of mummification paid attention to the unique structure of the graves (called Hoegwakmyo or the grave with lime soil mixture barrier) where the Joseon people had been laid to rest[38]. During the Joseon period, lime, red clay, and sand (called sammul or lime soil mixture) were blended, in given proportions, to construct the Hoegwakmyo tomb.

The mixture was poured around the coffin and once hardened, it completely sealed the grave. Since the Korean mummies were rarely found in partially or destroyed Hoegwakmyo graves[39], it can be concluded that the sealing itself played a major role in promoting the mummification[40]. It was also noted that a large amount of clothing was used to fill the coffins[41]. The use of textiles combined with the sealing produced a relative shortage of oxygen inside the coffin, hence retarding biodegradation of all the organic matter contained within.

In ancient history, in order to preserve the bodies of politically important figures, after their demise, various mechanisms were adopted to emphasise the physical potency and importance, even after death of these iconic figures.

Perhaps one of the strangest ways that people in the past tried to cure what ailed them was the alleged gruesome practice of “mellifying”[42] people or saturating them and embalming them with honey for the purpose of creating a mysterious all-healing confection; a process that began in life and continued well after death.[43] This was another mechanism of managing dead people in a living world. Other than food and ointments to cure various maladies, this also would not be the first case of honey being used to preserve human remains either, and there are many cultures in which honey has been used for this purpose.

There seems to be a long historical link between honey and rituals of death and burial. In many cultures, it was desirable to prevent the decomposition of corpses, and additionally some cultures viewed honey as a sacred, pure substance which in some cases could sometimes even bestow a corpse with the ability to be revived from the dead. The Egyptians, Babylonians, Persians, Assyrians, Spartans, Byzantines, and Arabs all made use of honey as a substance for embalming the dead of important members of society. The Burmese coat the corpses of high-ranking priests with a layer of honey as well, and often use honey as a way to temporarily preserve corpses awaiting burial.

Many historical figures are known to have been embalmed with honey as well. Alexander the Great [44]is said to have ordered that his body be embalmed with honey, and upon his death he was placed in a golden coffin filled with the purest of white honey and taken back to Macedonia.

Other famous figures were similarly preserved with honey. The body of King Edward I of England[45], who died on 7th July 1307, as he was on his way to wage war in Scotland and kill thousands of Scots, when he developed dysentery and demised. His embalmed body was brought south and buried in Westminster Abbey. was found to have hands and a face that were remarkably well preserved due to having been coated with a layer of wax and honey. Although in none of these cases are the corpses known to have endured a procedure like that described by Li for the Mellified Man[46], and none of them were consumed for healing purposes, it certainly shows that honey has long been closely entwined with death and that bodies can be successfully preserved for long periods of time with honey.

The Indonesia’s Torajan[47] people keep the bodies of their relatives to “live” at home with them, sometimes for years after their deaths. They provide the corpses with their own rooms; they are washed, and their clothes are regularly changed. Food and cigarettes are brought to them twice a day and they have a bowl in the corner that acts as their “toilet”. The bodies of the dead are embalmed by being injected with a preservative called Formalin, which prevents the bodies from decomposing.

Scientific embalming is a technique used to preserve the dead. Several doctors of Jewish origins owe their lives to knowing about the process of modern embalming[48]. Upon the deaths of Vladimir Lenin[49] and Joseph Stalin[50], their bodies were embalmed by a Jewish doctor. The body was then placed in state and queues of Russians in the former Soviet Union waited in harsh climatic conditions, in Moscow, to pay the last homage to the great Soviet Leader. Stalin had been the despotic dictator of the Soviet Union for nearly 30 years. He is now considered responsible for the deaths of millions of his own people through famine and purges, when his death on 5th March but was announced to the people of the Soviet Union on March 6th, 1953[51], many wept. Stalin had led them to victory in World War II against Nazi Germany[52].

Embalming was initially not accepted, as a means of preservation and disposal of the human body after death by the public. However, it was used extensively during the American Civil War, when the mortal remains of thousands of dead soldiers, on both sided had to be repatriated to their hometowns from the frontlines. Embalming was finally accepted after the body of the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln was embalmed and placed instate for viewing by the citizens[53]. Furthermore prior to his death he also had the body of his 11-year-old son, Willie, embalmed when he died from typhoid[54].

Today embalming is routinely used for transport of dead soldiers from global wars, repatriation of the dead to their home countries, important political figures who lie in state for many days, such as the late president Nelson R. Mandela[55] in Pretoria, South Africa and many others. This philosophy was also used in its primitive form in Spain when the great hero, El Cid [56]was killed in battle against the Moors and his crudely embalmed body was placed in a cathedral in San Pedro to emphasise his physical prowess and political importance even after death, that he is not subject to degradation as other mortals.

Newer techniques such as cryopreservation[57] is used in the 21st Century, where a body is rapidly frozen after death to prevent biodegradation in the hope that a cure will be found in future for the condition that was the cause of death of the person ab initio and that body would then be resuscitated back to life, in the future.

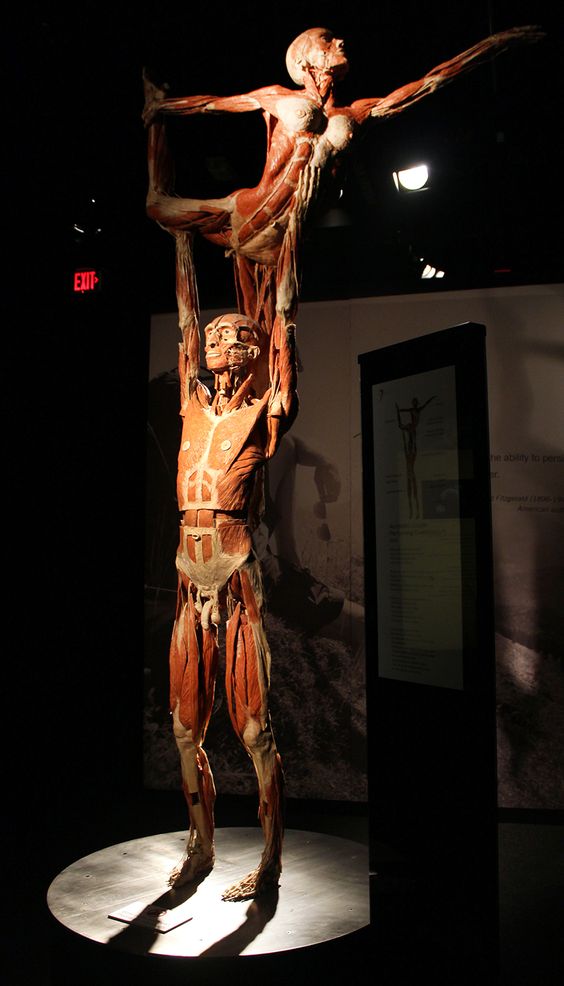

Plastination[58] is another 21st Century innovation to eternally preserve the dead body. It is a patented process formulated by a medical doctor Gunther von Hagens[59] whereby the entire body is replaced of all organic tissue after death by a patented silicone compound under vacuum and eternally preserved. Professor von Hagen has used this technique to hold the Body Worlds[60] exhibition globally showing intricately dissected human bodies in various poses, almost elevating the process to a 21st Century art form. The plastinated bodies have received divergent opinions and reviews about the ethics of plastinating human bodies for display to general public.

Finally, if the above processes of interment in the ground, ocean funerals, like that of Osama bin Laden[61] by the United States Navy after his execution, river funeral in the Ganges River in Varanasi, in India during the SARS Cov-2 pandemic. cremations, mummification, mellification in honey, freezing in cold storage, refrigerated containers, used to store slaughtered cattle during transport, cryofreezing for future resurrection, plastination, humanoid presently have the option of space funeral, interment on Mars and finally, immortalising your loved ones as an eternal, diamond.

This process of turning 100grams of human ashes, following cremation, into a piece of jewellery, as a diamond ring, a one carat diamond pendant or a ten carat diamond trophy, is presently offered by a private company in the United States. This uses the technology that is used by nature, over millions of years to convert carbon, coal, to raw, natural diamonds, which are then crafted in fine, expensive jewellery, to adorn the fingers and neck of some beautiful creation of the Lord, during her appointed term on earth. The technique used is compressing the ashes of the cremated deceased, under high pressure and intense heat, converting the carbon ashes into an industrial diamond. Therefore, the Prophecy of Prophet Jehovah, which states, “Ashes to ashes and dust to dust”[62], is negated. However, here we have “Ashes to Diamonds[63]” as an elegant remnant, eternal and aesthetically beautiful reminder of the disposed body of the beloved deceased, for posterity.

Therefore, while the original goal of preserving dead bodies was to prepare the deceased for their life in the hereafter, has now, paradoxically revealed their cause of death in ancient times, by using the latest research technology available to the 21st Century. However, the main motivation for any of these means of disposal of the human body, after death including mummification, are funereal customs based on religion, culture, tradition, and scientific breakthroughs over the centuries, to be prepared for humanoids to visualise and study, thousands of years later, were all tailored in the quest of humankind for an eternal presence after death. The processes also make the existence of the deceased, in the hereafter, as comfortable as possible for them, as well their acceptability to the supreme owner of their indefinable souls. The funereal customs undertaken by the living relatives, also given them solace, that they have fulfilled and discharged their obligations to the deceased.

The bottom line is that SARS Cov-2 pandemic has created a body disposal problem, globally, with the enormous number of deaths and how to dispose of the mortal remains of humanoids. Globally, the SARS Cov-2 pandemic has officially infected 169,487,389, with 3,523,506 deaths and has reached epic proportions[64]. The total doses of vaccines administered is only 1,806,457,958, as reported on 29th May 2021 at 0920 GMT, for the global population of over 6 billion humans. Land for burial of the deceased is at a premium, where interment is prescribed by the respective religion of the deceased, faculties are at critical levels or totally depleted.

The problem is further compounded by the evolution of newer variants of the virus, which are highly infective and transmissible. Clearly humanoids are at an unprecedented level of risk of decimation and possible extinction, as previous great civilisations did, this time caused by the invisible bioterrorist. The question which must be raised: is this a human, self-made catastrophe, or the retribution of the Lord against the ever-transgressing humanoids?

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abrahamic_religions

[2] https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+4&version=NLV

[3] https://goodnewsaboutgod.com/studies/spiritual/home_study/cain_abel.htm

[4] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Neanderthal

[5] https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

[6] https://www.transcend.org/tms/2021/05/covid-19-pandemic-body-disposal-crisis-what-to-do-with-dead-people-in-a-living-world-part-1/

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mummy

[8] Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2018, Article ID 6215025, 12 pages, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6215025

[9] T. A. Cockburn, E. Cockburn, and T. A. Reyman, Mummies, Disease, & Ancient Cultures, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2nd edition, 1998

[10] D. H. Shin, Y. H. Choi, K.-J. Shin et al., “Radiological analysis on a mummy from a medieval tomb in Korea,” Annals of Anatomy, vol. 185, no. 4, pp. 377–382, 2003.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taphonomy

[12] D.-S. Lim, I. S. Lee, K.-J. Choi et al., “The potential for non-invasive study of mummies: validation of the use of computerised tomography by post factum dissection and histological examination of a 17th century female Korean mummy,” Journal of Anatomy, vol. 213, no. 4, pp. 482–495, 2008.

[13] D. H. Shin, I. S. Lee, M. J. Kim et al., “Magnetic resonance imaging performed on a hydrated mummy of medieval Korea,” Journal of Anatomy, vol. 216, no. 3, pp. 329–334, 2010,

[14] S. B. Kim, J. E. Shin, S. S. Park et al., “Endoscopic investigation of the internal organs of a 15th-century child mummy from Yangju, Korea,” Journal of Anatomy, vol. 209, no. 5, pp. 681–688, 2006.

[15] M. J. Kim, Y. Kim, C. S. Oh et al., “Anatomical Confirmation of Computed Tomography-Based Diagnosis of the Atherosclerosis discovered in 17th Century Korean Mummy,” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 3, p. e0119474, 2015.

[16] D. H. Shin, C. S. Oh, J. H. Hong et al., “Paleogenetic study on the 17th century Korean mummy with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 8, p. e0183098, 2017.

[17] Y.-S. Kim, I. S. Lee, C. S. Oh, M. J. Kim, S. C. Cha, and D. H. Shin, “Calcified pulmonary nodules identified in a 350-year-old joseon mummy: The first report on ancient pulmonary tuberculosis from archaeologically obtained pre-modern Korean samples,” Journal of Korean Medical Science, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 147–151, 2016.

[18] Y. Kim, I. S. Lee, G. Jung et al., “Radiological Diagnosis of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia in 17th Century Korean Mummy,” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 7, p. e99779, 2014.

[19] I. Hershkovitz, M. Spigelman, R. Sarig et al., “A Possible Case of Cherubism in a 17th-Century Korean Mummy,” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e102441, 2014.

[20] M. Seo, S.-M. Guk, J. Kim et al., “Paleoparasitological report on the stool from a medieval child mummy in Yangju, Korea,” Journal of Parasitology, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 589–592, 2007.

[21] D. H. Shin, D.-S. Lim, K.-J. Choi et al., “Scanning electron microscope study of ancient parasite eggs recovered from Korean mummies of the Joseon Dynasty,” Journal of Parasitology, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 137–145, 2009.

[22] https://www.bing.com/search?q=coprolites+definition&cvid=413783f67a8e4466ab3f0c79aafd24c7&aqs=edge.1.0l7.8875j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531

[23] M. Seo, A. Araujo, K. Reinhard, J. Y. Chai, and D. H. Shin, “Paleoparasitological studies on mummies of the Joseon Dynasty, Korea,” The Korean Journal of Parasitology, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 235–242, 2014.

[24] M. Seo, C. S. Oh, J. H. Hong et al., “Estimation of parasite infection prevalence of Joseon people by paleoparasitological data updates from the ancient faeces of pre-modern Korean mummies,” Anthropological Science, vol. 125, no. 1, pp. 9–14, 2017.

[25] https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/trematodes-flukes/introduction-to-trematodes-flukes

[26] M. Seo, C. S. Oh, J. H. Hong et al., “Estimation of parasite infection prevalence of Joseon people by paleoparasitological data updates from the ancient faeces of pre-modern Korean mummies,” Anthropological Science, vol. 125, no. 1, pp. 9–14, 2017.

[27] D. H. Shin, Y.-S. Kim, D. S. Yoo et al., “A Case of Ectopic Paragonimiasis in a 17th Century Korean Mummy,” Journal of Parasitology, vol. 103, no. 4, pp. 399–403, 2017.

[28] D. H. Shin, C. S. Oh, S. J. Lee et al., “Ectopic paragonimiasis from 400-year-old female mummy of Korea,” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 1103–1110, 2012.

[29]History of the Joseon dynasty – Wikipedia

[30]L. X. Peng and Z. B. Wu, “China: the Mawangtui-type cadavers in China,” in Mummies, Disease & Ancient Cultures, A. Cockburn, E. Cockburn, and T. A. Reyman, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998.

[31] A. C. Aufderheide, The Scientific Study of Mummies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003.

[32] Benkantongxunyuan, “Some issues related to the study of ´ female body excavated from the Mawangdui tomb No. 1,” Wenwu, vol. 7, pp. 74–80, 1973.

[33] G. Z. Zheng, W. H. Feng, Y. H. Boa, J. N. Xue, and Y. S. Ying, “Microscopic and submicroscopic studies on the peripheral nerve and the skeletal muscle of the female. cadaver found in the Han Tomb No.1,” Scientia Sinica, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1095– 1098, 1979.

[34] https://www.history101.com/lady-dai-xin-zhui/

[35] C. Lee, D. Oscarson, and S. Cheung, “The preservation of a cadaver by a clay sealant: Implications for the disposal of nuclear fuel waste,” Nuclear and Chemical Waste Management, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 65–69, 1986.

[36] H.-Y. Yeh and P. D. Mitchell, “Ancient human parasites in ethnic Chinese populations,”The Korean Journal of Parasitology, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 565–572, 2016.

[37] C. S. Oh, I. U. Kang, and J. H. Hong, “An Experimental Assessment of the Cause of Mummification in the Joseon Period Burials, Republic of Korea,” Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 117–122, 2018.

[38] M. H. Shin, Y. S. Yi, G. D. Bok et al., “How did mummification occur in bodies buried in tombs with a lime soil mixture barrier during the Joseon Dynasty in Korea?” in Mummies and Science World Mummies Research, P. A. Pena, R. M. Martin, and A. R. Rodriguez, Eds., pp. 105–113, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2008. [44] C. S. Oh and D. H. Shin, “

[39] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diff-erence-in-Hoegwakmyo-grave-construction-A-at-the-initial-and-B-late-stages-In_fig4_319893189

[40] C. S. Oh and D. H. Shin, “Making an animal model for Korean mummy studies,” Anthropologischer Anzeiger, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 469–488, 2014.

[41] E.-J. Lee, C. S. Oh, S. G. Yim et al., “Collaboration of archaeologists, historians and bioarchaeologists during removal of clothing from Korean Mummy of Joseon Dynasty,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 94–118, 2013.

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mellification

[43] https://mysteriousuniverse.org/2015/05/the-bizarre-honey-mummies-of-ancient-arabia/

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_I_of_England

[46] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mellified_man

[47] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/indonesia-village-dead-corpses-dress-up-toraja-indonesia-south-sulawesi-alive-annual-festival-tourist-a7694541.html

[48]https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-the-quest-to-preserve-lenins-body-helps-the-living

[49] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-the-quest-to-preserve-lenins-body-helps-the-living

[50] https://www.thoughtco.com/body-of-stalin-lenins-tomb-1779977

[51] http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1954-2/succession-to-stalin/succession-to-stalin-texts/announcement-of-stalins-death/

[52] https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/stalins-victory-the-soviet-union-and-world-war-ii/

[53] https://connectingdirectors.com/54261-lincoln-embalming

[54] http://www.milwaukeeindependent.com/syndicated/a-lifelike-death-how-the-embalming-of-president-abraham-lincoln-started-the-funeral-industry/

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson_Mandela

[56] https://www.britannica.com/biography/El-Cid-Castilian-military-leader

[57] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryopreservation

[58] https://www.vonhagens-plastination.com/pages/medical-teaching-specimens/von-hagens-plastination.php/plastination

[59] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/gunther-von-hagens-human-body-corpse-worlds-exhibition-london-corpse-display-a8570581.html

[60] https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/body-worlds-exhibition_uk_5bb74288e4b01470d0509814

[61] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osama_bin_Laden

[62] https://www.bing.com/search?q=ashes+to+ashes+dust+to+dust&cvid=16f9210956404890a81104b1934748db&aqs=edge.1.0l7.7344j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531

[64] https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits):

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits):

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Pandemic

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 31 May 2021.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Covid 19 Pandemic: Body Disposal Crisis–What to Do with Dead People in a Living World? (Part 2), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

COVID19 - CORONAVIRUS: