Sudan: A Failed Mediation Process

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, 10 Jul 2023

Meg-Ann Lenoble | Cordoba Peace Institute Geneva - TRANSCEND Media Service

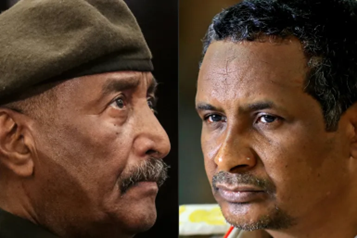

27 Jun 2023 – The United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Sudan, Volker Perthes, who is also Head of the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNAMITS), told the Security Council on 20 March 2023 that the “return to peace is near”. [1] To date, hundreds of people have been killed and injured in Sudan and sexual and gender-based violence as increased, particularly against women, as a result of the war that broke out on 15 April 2023, less than a month after this declaration. This conflict opposes the Sudanese army of Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Chairman of the Transitional Military Council of Sudan which rules the country, and the “Rapid Support Forces” (RSF), paramilitaries led by Mohamed Hamdan Daglo nicknamed “Hemedti”, Vice-President of the Transitional Sovereignty Council of Sudan at that time.

The two generals had jointly orchestrated the October 2021 coup, leading to the fall of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok representing the civilian government, thus leading them both to the governance of Sudan. Allies in the past, how can we explain this reversal? [2] How can we explain the lack of predictability on the part of the international community, which has not been able to accomplish its main mission of protecting civilians? Given the experience of the international community in the prevention, management and resolution of conflicts, how can we justify the non-anticipation of the use of lethal armed force in urban areas? How did the mediation process fail?

As of 31 May 2023, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) counts more than 1.65 million newly displaced people, including 425,000 outside Sudan. The country now at war is going through an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The capital Khartoum is plunged into an unprecedented catastrophic situation. The city has emptied, millions of people have fled, looted houses are occupied by the RSF and daily fighting hinders access to basic needs.

People who cannot afford to leave their localities are regularly deprived of access to water, food and medical care. The war is also having an impact as far away as Darfur. In crisis for 20 years, this area is once again plagued by widespread ethnic violence. [3] The tribal militias of Darfur [4] are also mobilized to respond to the resurgence of dramatic ethnic violence described by the late Masalit Governor of West Darfur, Khamis Abdallah Abakar as “genocide”. His assassination on 14 June 2023, allegedly by the RSF [5], illustrates the gravity of the situation.

A political framework agreement was signed on 5 December 2022 between the military and a large part of the civilian opposition in Khartoum. The trilateral mechanism composed of UNAMITS, the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and QUAD (the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States) have worked to formalize the willingness of each of the parties to work together to bring the Sudan out of a major political crisis. This period of democratic transition, initiated in 2019, was expected to lead to the conclusion of a lasting political agreement.

Specifically, the appointment of a two-year transitional government for the formation of an inclusive civilian government considering the voices of women and new generations, the revision of the constitutional text as well as the conduct of democratic elections were key objectives of the agreement. [6] According to the United States, guided by Joe Biden’s foreign policy,[7] erecting democracy worldwide as a bulwark against autocratic influences such as China and Russia, this process seemed to be a “credible path” to lead Sudan and the Sudanese towards a political stabilization. However, tensions between the two parties had been rising since the signing of the December 2022 agreement [8] which finally proved to be a failure.

The deterioration of Sudan’s political and security situation is hugely regrettable, four years after an extraordinary non-violent civic revolution carried out by the entire population, including young people and women embodied by Alaa Salah. [9] The international community has unfortunately not been able to support these activists to make this massive movement for peaceful change a reality. Indeed, the institutions involved in the process of resolving the conflict have not ceased to legitimize the protagonists of this war, who came to power by force of arms.

Exchanges and discussions with these personalities were valued as part of a “democratic transition” without taking into account the contradictory external signals. The outbreak of this war is described by some actors as “the failure of international diplomacy”. [10] This model of urban warfare in the capital of seven million inhabitants was unimaginable for the international community, which had turned Khartoum into a “family station” for these expatriates. Khartoum had not been the scene of such a high-intensity war since 1885.

At the UN Security Council meeting on 20 March 2023, warnings were shared by several nations including France and the A3 (Gabon, Ghana, Mozambique) regarding the high levels of intercommunal tensions that persisted and the recruitment of ongoing combatants that were not necessarily indicators of peace. Moreover, the rearmament of each of the belligerents over more than a year does not seem to have been noted as an indicator of potential future armed conflict. [11]

In addition, the need to work through an inclusive process that is representative of all parts of Sudanese society to reach a broad consensus on the adoption and development of a new constitution has been reiterated by several countries. The Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Sudan thus reassured his audience by confirming the good ownership of the peace process initiated by all Sudanese despite the fact that several opposition parties, resistance committees and former rebel groups had been excluded from the process. [12]

It was also clarified that under this agreement, the army would not participate in political discussions since it would resume its original functions of guaranteeing unity and territorial integrity without politicization or ideology. This raises the question of the nature of the inclusiveness of the process in a context where the military is in power and the primary beneficiary of the political and financial benefits of its current positions.

In view of current events, the mediation process has clearly failed. Several elements could have been taken more into account in the methodology and more specifically in a context-sensitive analysis respecting the principle of “do no harm”.

First of all, the dynamics of time is an essential element to be considered both in the methodological failure of the process, but also in the solutions proposed and their perceptions by the parties to the conflict. The urgency of the international agenda has not been in line with the realities on the ground and has not allowed for an efficient and coherent reading of the situation. Indeed, the major point of tension was the integration of the RSF into the army and more particularly the duration of this process. Al Burhan insisted that this be effective within two years, while Hemedti wanted a gradual transition over the next ten years.

According to Magdi el Gizouli, a Sudanese researcher and member of the Rift Valley Institute, [13] the perception of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) was that this option of gradual integration over ten years would never succeed. For his part, for Hemedti the two proposed years of transition were synonymous with “tomorrow” and concretized the loss of control of his paramilitary team starting with the integration of the generals as demanded by Al Burhan. Apart from these two options, completely unthinkable for either party, there has been no satisfactory alternative solution from the international mediators. The mediation process did not provide the necessary time for high-stakes discussions. Indeed, all communications relating to this peace process have stressed the need for agreement and a “rapid” transition. This approach, contradictory to the success factors of non-violent conflict resolution mentioned in the United Nations publication entitled “UN Guidelines for Effective Mediation”, [14] has exacerbated latent tensions. [15]

Then, given the profiles of the generals, it was obvious that they would not want to conclude the negotiations, but rather keep their political power and national and regional influence. The stakeholders were caught up in the “economic” rationality of the stakes, to the detriment of the democratic and socio-popular priorities carried by a strong Sudanese civil opposition. Indeed, the alliance between the two generals in the 2021 coup was opportunistic. They each have their own agenda, their own ambitions and international financial and logistical support motivated by divergent interests.

After providing private security for dictator Omar al-Bashir, the RSF is the armed wing of Hemedti’s thriving and ever-expanding commercial enterprise covering Sudanese gold mining and export operations. He has built up a colossal fortune and has much to lose in this process of integrating his paramilitary forces into the regular armed forces. Hemedti is the head of a private transnational mercenary company that has been hired by the Gulf monarchies to fight in Yemen and deals with the Wagner Group. Its external backers are influential, they have economic interests in Sudan and have resources to fight in the long term. Finally, Hemedti’s pride and determination emanates from the constant and historic humiliation of these troops who are feared, ridiculed and denigrated. The base of Hemedti belongs to various tribes united in their belief in having been deprived of recognition and political power. [16] They see here a concrete opportunity for revenge.

Finally, it would have been relevant to avoid the multiplicity of international mediation channels, to privilege and listen to local mediators who had understood the security issue between FSR and SAF and to maximize the coordination of the powers involved. The multitude of international actors involved in this peace process was not conducive to political stability. [17] This model of mediation is also the subject of particular warning from the “United Nations Guidelines for Effective Mediation”.

The imposition of the external political agendas of the regional powers, the United States, Russia, Israel and the European Union, have once again demonstrated the counter-productivity in a process of transition and peacekeeping and the deadly damage that this causes to the populations. [18] Moreover, the lack of international coordination and the presence of foreign powers with divergent agendas contribute to the risk of regionalisation of the crisis. It remains strong in view of the long-term economic and strategic challenges, the cross-border ethnic links between populations and the humanitarian consequences of the crisis. [19]

While the mediation process before the recent confrontation is open to criticism in view of the reasons exposed, the current mediation process also faces potential areas for improvement and risks being doomed to another failure if the strategic lines are not readjusted.

Talks between belligerents had started in mid-May in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, but the Sudanese army suspended discussions accusing the RSF of a lack of respect for the commitments made in the various agreements signed. [20] Despite the various “ceasefires” facilitated by Washington and Riyadh in recent weeks, abuses and violence are continually reported.

Therefore, in light of these elements, at the beginning of June 2023, the United States imposed its first sanctions in order to hold accountable all parties jeopardizing the stability of North-East Africa. [21] They particularly targeted companies controlled by the RSF leader that are located in the United Arab Emirates and Khartoum, as well as two defense industries of the Sudanese army. It remains to be seen whether sanctions against those two parties to the conflict alone will be an effective strategy. These sanctions could have a limited impact in view of the regional financial and logistical alternatives available to the two generals.

This new mediation process aimed solely at the application of a “ceasefire”, once again highlights the question of the methodological approach in terms of mediation and conflict transformation. Indeed, in view of the current stakes and the repeated non-respect of these “ceasefires” to the detriment of the populations, it would be interesting to be able to analyze more the positions, interests and needs of each of the parties who seem to want to go to continue this war until there is a single winner.

Moreover, the question arises again of which parties, nations, institutions and interlocutors can and should position themselves as mediators for the success of such a process? In view of the current mediators, their underlying political and economic interests, [22] “impartiality”, an indispensable element for a healthy [23] and positive mediation for the population, can be questioned. Other alternatives should be explored to resolve this multidimensional crisis through a coordinated multi-track approach that promotes the voice of local mediators and analysts.

It is important to remember that the field of conflict transformation has become largely professionalized and makes it possible to give credibility to the mediation efforts undertaken. It is a discipline that is the subject of constant research, taking into account the lessons of current and past processes and which provides the tools to identify the potentialities and limits of the mediation processes undertaken in order to prevent, manage and resolve in a non-violent manner any conflict. The United Nations has an “innovative” cell dedicated to supporting mediation efforts in its teams working on peace promotion. [24]

Despite these tools and means deployed for conflict resolution, it appears that in this case the processes initiated were damaging. In light of the formula of peace practice conceptualized by Galtung in 2014 ((Equity x Harmony) / (Trauma x Conflict)), [25] a major and non-negotiable imbalance focused on the construction of future equity and cooperation for equal and mutual benefit, particularly in the context of security sector reform. The mediation process did not result in compatible/conflicting goals being compatible. A step-by-step approach that favours time, patience and modesty has been lacking, although these are essential ingredients mentioned in the majority of mediation studies and manuals. [26] Once again, the hegemonic model of peacebuilding promoted by the West, implementing top-down models and wanting to impose its vision of peace, generates additional violence and instability of the system it initially seeks to stabilize. [27]

These methodological failures exploited by autocratic countries or other private actors such as Wagner lead to a crisis of confidence in international bodies for the promotion and maintenance of peace. Sudan’s Foreign Minister declared the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Sudan persona non grata on 9 June 2023, accused of inflaming the conflict, and demanded his immediate withdrawal. On 16 June, Mali called for the non-renewal of the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), created ten years ago, and also demands its departure without delay. [28] This decision is supported by Burkina Faso, which requested the repatriation of its MINUSMA troops as soon as possible [29] in a press release dated June 18, 2023. The accumulated rejection of the institutions set up by the West in the aftermath of the Second World War to fight against the emergence of armed conflicts will have serious consequences on the political and security situation of these countries,[30] on the protection of populations and on the strategic positioning of the West in the new world order.

References

[1] Sudan: “The return to peace is near”, promises the Head of UNAMID before the Security Council

[2] Sudan’s Descent into Chaos: What Washington and Its Arab Partners Must Do to Stop the Shootout

[3] Sudan: Darfur, epicentre of the war

[4] Sudan: War between Khartoum rivals takes on an ethnic dimension in Darfur

[5] “All the dogs are gone”; “Dar Masalit is for the Arabs now”

[7] How U.S. Efforts to Guide Sudan to Democracy Ended in War

[8] Stopping Sudan’s Descent into Full-Blown Civil War

[9] Sudan: Alaa Salah, the revolution by singing

[10] The Revolution No One Wanted

[11] Two rival generals threaten to plunge Sudan into chaos

[12] A Critical Window to Bolster Sudan’s Next Government

[14] About the UN Guidance for Effective Mediation

[15] Joshua Craze, Gunshots in Khartoum — Sidecar

[16] The many faces of Sudan’s General Hemedti, a ‘son of the desert’

[17] Diplomatic ballet in Sudan, a fragile and coveted country

[18] Sudan and the New Age of Conflict: How Regional Power Politics Are Fueling Deadly Wars

[19] Sudan Conflict: Assessing the Risk of Regionalization

[20] Sudan army suspends participation in Jeddah ceasefire talks

[21] US imposes first sanctions over Sudan conflict

[23] Rognon Frédéric, “What is mediation?”, Études, 2016/6 (June), p. 53-64.

[24] UN Mediation Support Unit

[25] Johan Galtung’s Peace Formula

[26] EU External Action – Peace Mediation Guidlines

[28] Security Council: Mali calls for immediate withdrawal of MINUSMA

[29] MINUSMA withdrawal: Burkina Faso hails Mali’s “courage”

[30] Mali withdraws consent to MINUSMA presence and calls for immediate withdrawal

Go to Original – cpi-geneva.org

Tags: Africa, Conflict Mediation, Cultural violence, Direct violence, South Sudan, Structural violence, Sudan, Violent conflict

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION: