Prisons as Sites of National Reconciliation or Continuing Hells

ASIA--PACIFIC, 1 Dec 2025

Sai Tun Aung Lwin | FORSEA - TRANSCEND Media Service

In Vietnam, prison, a colonial and wartime instrument of brutality, has been turned into a memorial museum contributing to national identity-building and reconciliation. Meanwhile, Myanmar’s prisons continue to operate as spaces of systematic violence under successive authoritarian regimes.

24 Nov 2025 – This article examines the contrasting trajectories of Hỏa Lò Prison in Vietnam and major prisons in Myanmar – Insein, Tharrawaddy, and Obo – to explore how societies confront, remember, or fail to transform their carceral pasts. Drawing on my firsthand visit to Hỏa Lò, I analyse how the site has shifted from a colonial and wartime instrument of brutality into a memorial museum contributing to national identity-building and, notably, reconciliation with former adversaries such as the United States. This transformation reveals how the Vietnamese state narrates sovereignty, victimhood, and resilience through selective memory and public heritage practices.

By contrast, Myanmar’s prisons continue to operate as spaces of systematic violence under successive authoritarian regimes. Rather than being reinterpreted as historical scars, they remain active tools of oppression, especially during the post-coup crisis. Through comparative reflection, I argue that the divergent fates of these prisons illustrate broader differences in political transitions, state legitimacy, and the construction of public memory.

The article ultimately raises a critical question: why has Vietnam been able to transform a site of colonial atrocity into a narrative of national healing, while Myanmar’s prisons remain frozen in cycles of fear and suffering? The comparison offers insights for future transitional-justice debates in Myanmar.

Hỏa Lò derives from Hao = fire, and Lo = furnace, stove, or kiln. It literally means “fiery furnace.” However, historically it carries a darker connotation because of the brutality inflicted there. In some contexts, it evokes the sense of ငရဲခန်း – a chamber of hell.

Before the French colonials built the prison, the area was a village called Phu Kham. In the 19th century, this village was distinctive within the Thang Long Citadel (the Vietnamese royal complex), known for its traditional ceramic craftwork – kettles, teapots, portable stoves. Hence the name Ha’o Lo’ (Fiery Furnace) became associated with the village. Its handicrafts were well-known.

Before the French colonials built the prison, the area was a village called Phu Kham. In the 19th century, this village was distinctive within the Thang Long Citadel (the Vietnamese royal complex), known for its traditional ceramic craftwork – kettles, teapots, portable stoves. Hence the name Ha’o Lo’ (Fiery Furnace) became associated with the village. Its handicrafts were well-known.

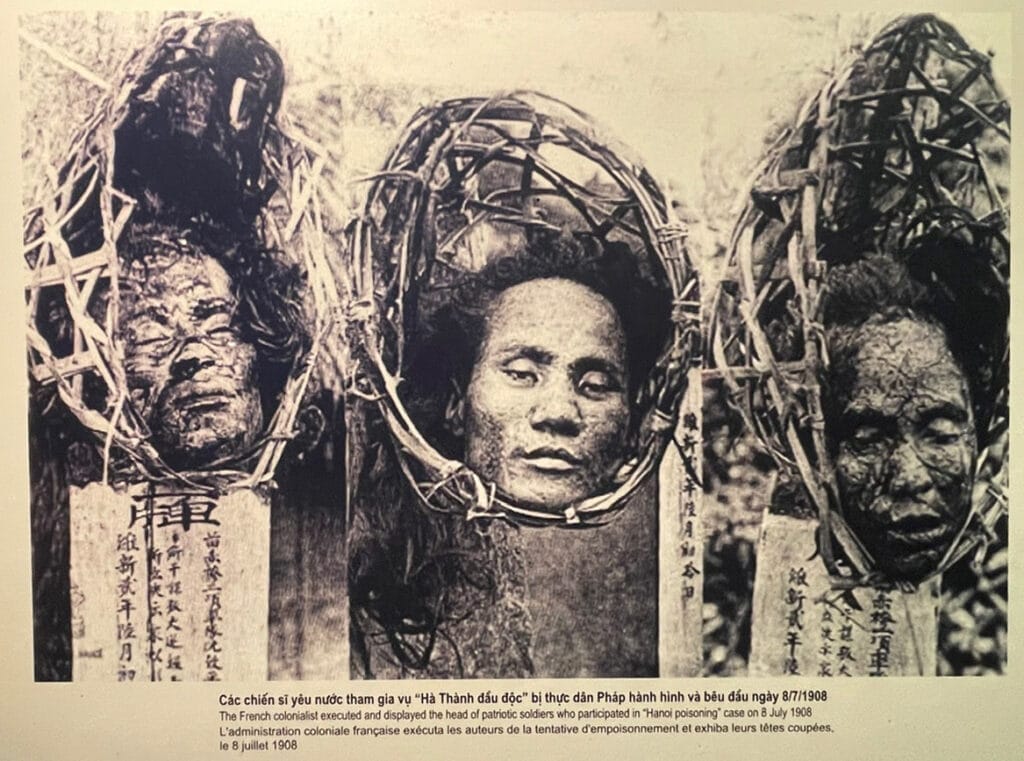

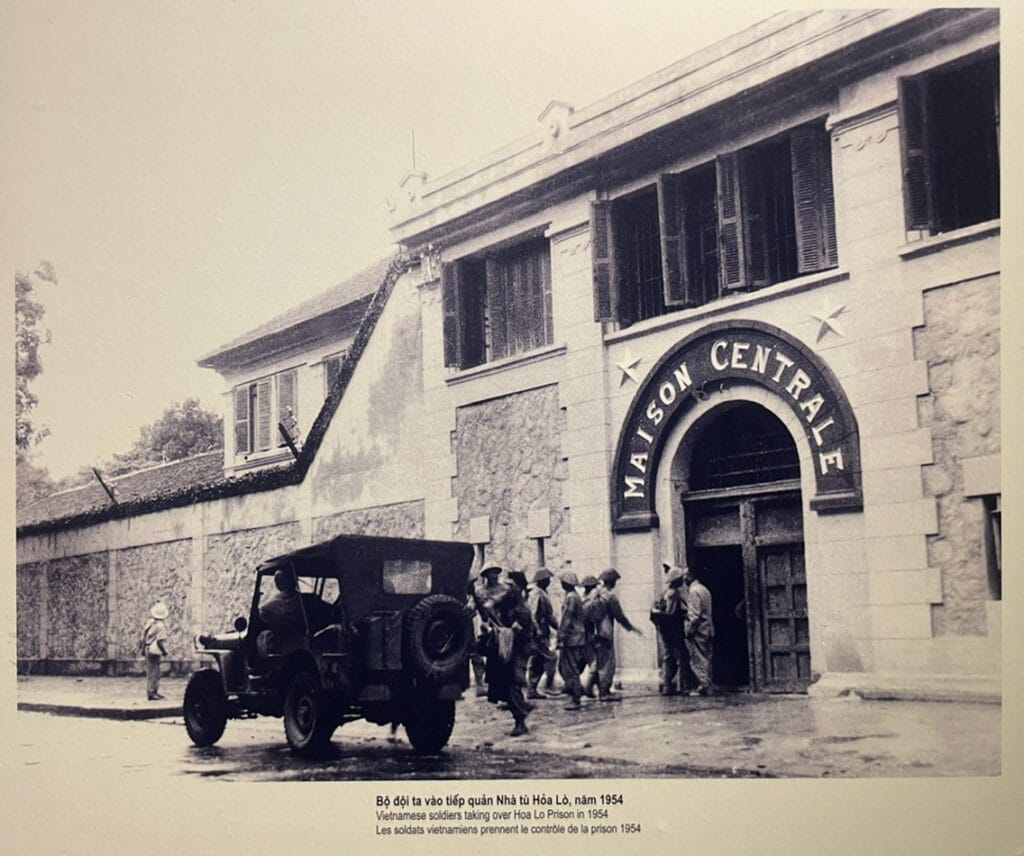

In 1896, the French colonialists built a prison on the site. Villagers, old pagodas, and communal houses were removed. The prison became a tool of autocratic rule, suppressing patriotic and revolutionary movements of the Vietnamese people. Throughout the colonial period, it was a special place for nationalists, communists, and patriots of Vietnam.

Built by the French in the 1890s, Hỏa Lò stands as a material symbol of colonial violence and domination. It embodies how colonial power suppressed nationalist movements through imprisonment, torture, and control over minds and bodies.

Many Vietnamese nationalists and patriots, including future communist leaders, were imprisoned there.

Today, the site has been transformed into a museum. Exhibits include the guillotine, iron shackles, belly chains, electric shock wires, and other torture instruments, underlining the brutality of colonial methods.

In that sense, Hỏa Lò is a scar, a wound left by imperial subjugation that still shapes Vietnam’s historical consciousness.

As the saying goes: the more they oppressed, the more things burst forth.

Even within cramped buildings and the strict discipline of colonial wardens, Vietnamese nationalists managed to mobilise and share political consciousness among patriots behind bars. The prison became a symbol of the Vietnamese struggle against colonial oppression.

A New Chapter: Reconciliation

In the Vietnam–US war era, the same prison held American POWs, including pilots such as John McCain, James Stockdale, and Jeremiah Denton. Between 1964 and 1973, hundreds of American pilots shot down over North Vietnam were imprisoned there – the chapter Americans most associate with Hỏa Lò.

Initially, some prisoners faced harsh conditions – poor food, unsanitary facilities, and interrogations – but later they were treated in line with the Geneva Conventions. From 1969 onwards, treatment generally improved and became more tolerable.

Some POWs later referred to the prison as the “Hanoi Hilton.”

Decades later, the site became part of diplomatic narratives, symbolising how former enemies could achieve reconciliation. John McCain, once a prisoner there, later visited Vietnam as a US senator and strongly promoted rapprochement. Many Vietnamese mourned his death in 2018 and recalled his role in reconciliation.

The museum now presents not only suffering but also mutual respect and peace-building after the war. It is a reminder that enmity can be transcended through reflection and dialogue.

Much of the complex was demolished in 1993 to make way for modern buildings, leaving a small portion preserved as a historical museum. Today it educates visitors on both Vietnam’s struggle for independence and the global conflicts that shaped the 20th century.

When I visited, I saw evidence from the colonial and Vietnam War eras alongside displays highlighting reconciliation between Vietnam and the United States.

Purposes of the Museum

Educate visitors

The exhibition teaches about the hardships of Vietnamese political prisoners under French colonial rule and their unwavering resistance.

Honour patriots

It serves as a memorial to the revolutionary spirit and sacrifices of those imprisoned there.

Foster national pride

By highlighting resilience and courage, it reinforces national pride and gratitude for independence.

Encourage reflection and reconciliation

Especially for Americans, it offers a space to reflect on how far relations have come.

Preserve historical artefacts

Artifacts, photos, and displays ensure the stories remain alive.

Global Comparisons

South Africa transformed its colonial and apartheid-era prisons, including Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was held, into museums.

In Iraq, Abu Ghraib prison was shut down due to security concerns. It remains a symbol of violations from Saddam’s era to the US-led invasion.

Hỏa Lò in Vietnam, Robben Island in South Africa, and Myanmar’s Insein, Tharrawaddy, and Obo prisons reveal how oppressive regimes and colonial rulers used incarceration to suppress dissidents and patriots.

Yet even during Myanmar’s NLD government, these infamous sites were never transformed into museums. Now, Aung San Suu Kyi’s house – No. 54 University Avenue Road – where she spent years under house arrest, also faces an uncertain future.

Only if these places are transformed into museums or centres for raising national consciousness can Myanmar truly approach peace. The current path offers no easy way forward.

_______________________________________________

Sai Tun Aung Lwin is a Shan/Myanmar journalist and researcher.

Tags: Burma/Myanmar, Colonialism, Colonization, Museum, Prisons, Vietnam

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.