Standing Still while History Screams

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 19 Jan 2026

Raïs Neza Boneza – TRANSCEND Media Service

A reflection on dignity, betrayal, and the fine art of losing without selling your soul.

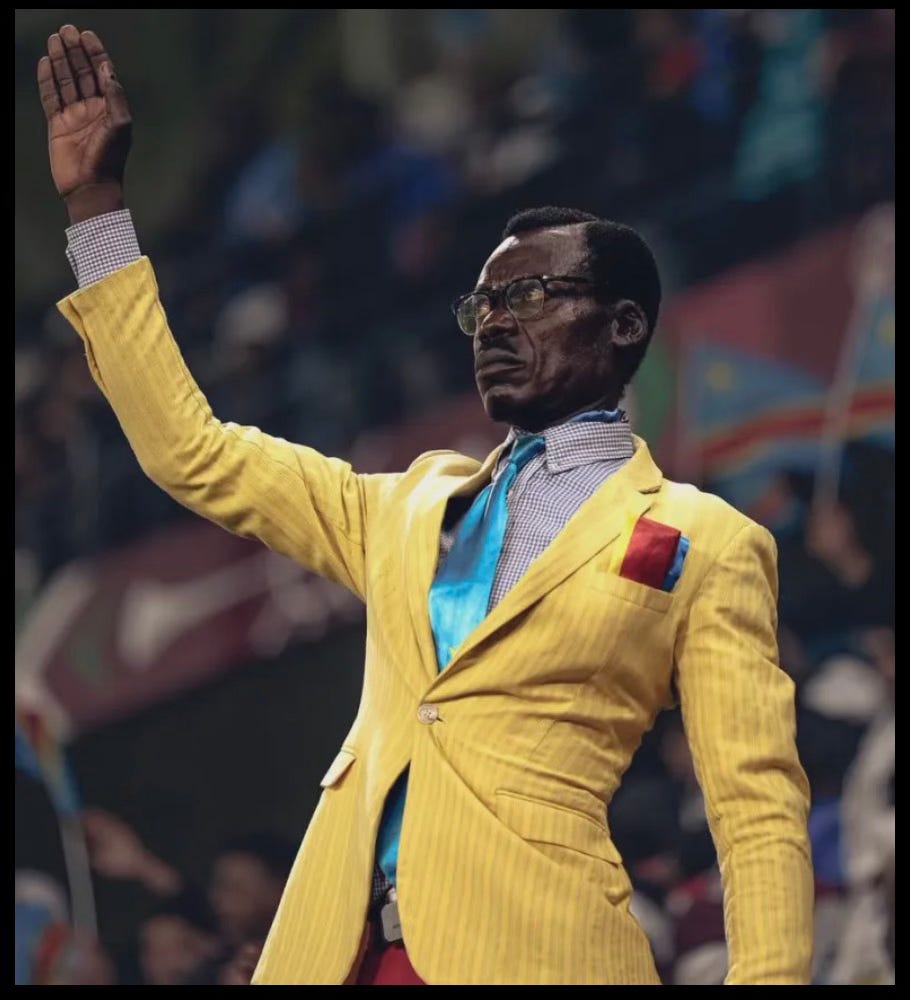

12 Jan 2026 – Because sometimes resistance doesn’t run, dribble, or score. Sometimes it stands still. At the Africa Cup of Nations, while sponsors blinked and pundits yelled, a Congolese man named Michel Kouka Mboladinga did something subversive: he refused to move. For seven hours. Match after match. Upright. Silent. Unbothered by the noise. A living statue of Patrice Lumumba.

He didn’t touch the ball, yet he dominated the tournament. This is not sports journalism. This is political anatomy. Lumumba taught us a scandalous idea in a world addicted to winning: it is better to lose without betrayal than to win by selling your people. Victory is cheap. Integrity is expensive. Most politicians go bargain-hunting anyway.

Michel Kouka’s stillness was not cosplay. It was verticality—moral posture in an age of permanent kneeling. While states prostrate themselves before empires, one man stood up. That’s why it hurt. That’s why it went viral. That’s why an opposing player mocked the posture—and then apologized. Symbols can be funny but until they cut.

When the DR Congo was eliminated in the 119th minute, Michel finally broke posture and cried. Those tears did more political work than a thousand press conferences. They reminded us that dignity is not abstract—it weighs on the spine.

Algeria: Where Revolutions Went to Be Taken Seriously

There’s an old truth revolutionaries know: Christians have the Vatican, Muslims have Mecca, and revolutionaries once had Algeria.

In 1960, when Congo gained independence and Algeria was still bleeding for it, Lumumba did something unforgivable: he recognized the Algerian provisional government before it had a fully liberated territory. That wasn’t diplomacy. That was heresy against the colonial order.

Algiers was not a capital. It was a sanctuary. Movements without a voice at the UN spoke from there. Fighters trained there. Ideas breathed there. From Cabral to Mandela, from the ANC to Congolese rebels, liberation had an address.

When Lumumba was assassinated in 1961—with Western fingerprints still warm—Algiers mourned as if it had lost a son. And then it acted. Support to Congolese resistance flowed through Algeria. Even Che Guevara coordinated aid from there. This is why history has a sense of irony sharper than satire.

Morocco: The Spa of Autocrats

Across the border, another geography formed. Morocco chose order over rupture, stability over justice, alliances over liberation. It became the lounge where friendly dictators rested. That’s why Mobutu Sese Seko, Lumumba’s executioner-by-proxy, is buried in Rabat. Not in Congolese soil. Not among ancestors. Exiled even in death. A man who preached “authenticity” now sleeps in foreign ground. History enjoys sarcasm. And Algeria held Moïse Tshombe—the man who helped deliver Lumumba—as a prisoner. Morocco keeps Mobutu as a relic. One land imprisons the crime. The other preserves it. This is not coincidence. This is political cartography.

Here is the problem Congo keeps dodging: you cannot invoke a martyr while honoring his executioners. You cannot chant Lumumba while kneeling in Washington. You cannot wear the costume of resistance while outsourcing sovereignty.

Today’s Congolese power speaks the language of independence but practices the grammar of dependency. The empire that approved Lumumba’s death is now asked to guarantee peace. Asking your assassin to babysit your children is not diplomacy—it’s amnesia with a suit.

And amnesia is costly.

A nation that does not mourn its dead loses its reflex to resist. Unwept blood doesn’t disappear. It lingers. It weakens. It confuses.

This is why Congo’s crisis is not only military or political. It is memorial.

From the rubber terror under Leopold to today’s coltan massacres, Congolese lives have been treated as renewable resources. Fifteen million then. Millions now. Yet the nation is told to dance, move on, reconcile—with whom, exactly?

Standing Is a Strategy

Algeria understands something Congo has been taught to forget: martyrs are not ghosts. They are foundations. The shaheed not in pas past tense, He is part of a civic infrastructure.

That’s why, in the stadium, before the match, Algerians honored Congolese victims from the East. Not as charity. As respect. Ignoring a martyr is sacrilege. Dancing over unburied bones is not joy—it’s dissonance.

Michel Kouka’s stillness created a moral short circuit. One man reminded millions that posture matters. That history watches. That ancestors don’t applaud betrayal. Congo will not recover through cosmetic elections, imported peace deals, or stadium theatrics. It will recover when it realigns its heroes and buries its lies.

When Lumumba stands above collaborators., when memory stops being negotiable; when sovereignty is practiced, not performed. Until then, one supporter standing still will continue to outplay presidents who keep kneeling.

At times, the highest form of resistance is stillness charged with refusal.

____________________________________________

Raïs Neza Boneza is the author of fiction as well as non-fiction, poetry books and articles. He was born in the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Former Zaïre). He is also an activist and peace practitioner. Raïs is a member of the TRANSCEND Media Service Editorial Committee and a convener of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment for Central and African Great Lakes. He uses his work to promote artistic expressions as a means to deal with conflicts and maintaining mental wellbeing, spiritual growth and healing. Raïs has travelled extensively in Africa and around the world as a lecturer, educator and consultant for various NGOs and institutions. His work is premised on art, healing, solidarity, peace, conflict transformation and human dignity issues and works also as freelance journalist. You can reach him at rais.boneza@gmail.com – http://www.raisnezaboneza.no

Raïs Neza Boneza is the author of fiction as well as non-fiction, poetry books and articles. He was born in the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Former Zaïre). He is also an activist and peace practitioner. Raïs is a member of the TRANSCEND Media Service Editorial Committee and a convener of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment for Central and African Great Lakes. He uses his work to promote artistic expressions as a means to deal with conflicts and maintaining mental wellbeing, spiritual growth and healing. Raïs has travelled extensively in Africa and around the world as a lecturer, educator and consultant for various NGOs and institutions. His work is premised on art, healing, solidarity, peace, conflict transformation and human dignity issues and works also as freelance journalist. You can reach him at rais.boneza@gmail.com – http://www.raisnezaboneza.no

Tags: Africa

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.