Harn Yawnghwe, an Extraordinary Life in Public Service & a Barricade against the Erasure of the Shan from Myanmar’s Memory (Part 2)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 2 Feb 2026

Maung Zarni | FORSEA – TRANSCEND Media Service

30 Jan 2026 – For half-a-century, Harn Yawnghwe has been pushing for federalism based on ‘ethnic group equality and inclusive society’ as the only twofold viable solution for peace and reconciliation in his native Myanmar.

“A Quiet but Determined Exile”

From Burmese cultural and Buddhist philosophical perspectives, we are explicitly advised against singing praise of anyone while he/she is still alive. For we assume that humans are corruptible creatures. A conclusive take on a person’s life, deeds and character can only be had after his or her passing.

Harn, on the far right, laughing at the photographer’s joke, with retired Professor U Kyaw Win (left, in Burmese attire), author of My Conscience: An Exile’s Memoir of Burma (2016) and Mr Abul Hassan Mahmood Ali, the then Foreign Minister of Bangladesh, at the Government House, Dhaka, 29 Nov 2017. Both Harn and U Kyaw Win were there as official guests of the FM to discuss Myanmar’s genocide of Rogingyas who became refugees in Bangladesh, before travelling on to Cox’s Bazaar where they went to see their fellow countrymen and woman in refugee camps.

(Photo courtesy of a Bangladeshi diplomat in attendance.)

A tragic case in point.

For nearly a quarter of a century, the world kissed the ground Aung San Suu Kyi walked on, only to eventually condemn the Burmese Nobel Peace Laureate and then State Counsellor for her complicitous silence on the ongoing atrocities against Rohingya people. Subsequently, the Burmese politician ended her studied silence and defended the allegations of genocide of Myanmar’s most vulnerable population of Rohingyas in Gambia vs. Myanmar case at the International Court of Justice.

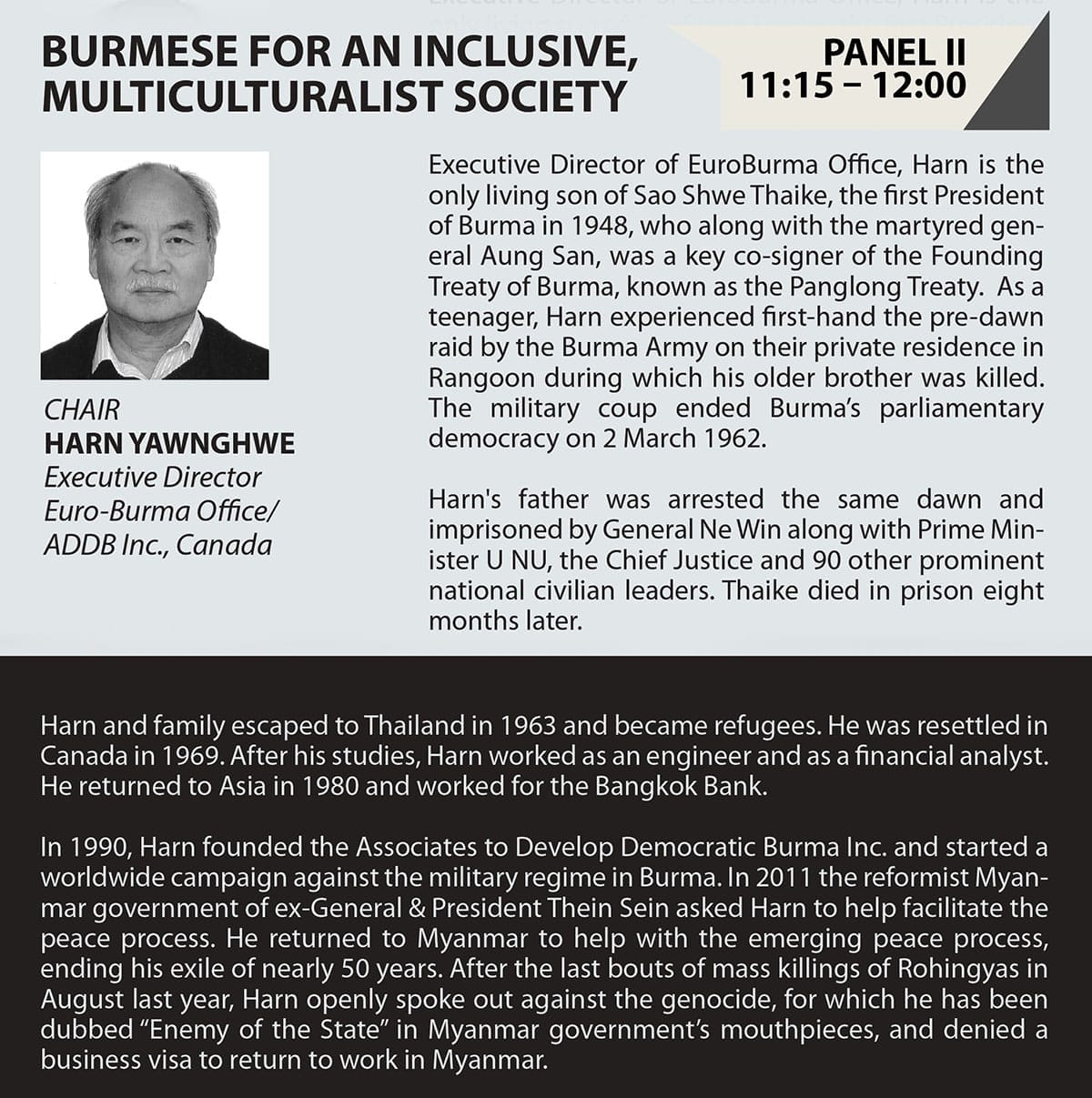

Harn’s bio in the program for the Berlin Conference on Myanmar’s Rohingya Genocide, Jewish Museum of Berlin, 26 March 2018.

In choosing to tell the semi-biographical tale of Harn Yawnghwe, a fellow political exile whom I have known for nearly three decades and have worked with as trusted colleagues in our various efforts for genuine change in our shared birthplace, I have felt confident that I don’t need to observe this cultural wisdom.

I am acutely aware that such an attempt runs the risk of being hagiographic. I trust my own trained intellectual habit of seeing things as they are, rather than through a pair of rose-tinted eyes of an admiring friend.

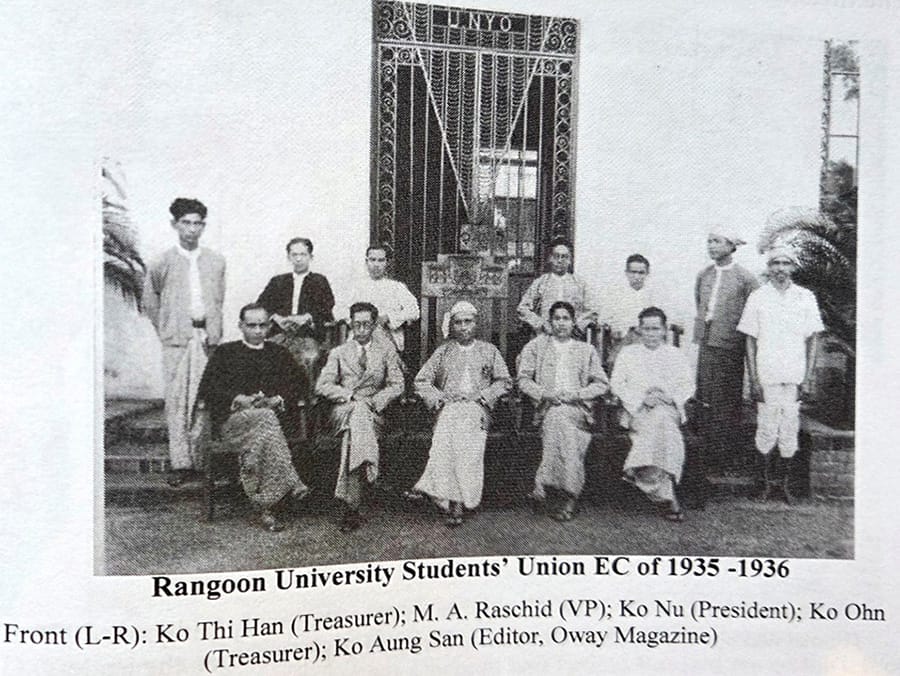

Growing up as a young man in the sleepy, isolated Mandalay, during General Ne Win’s military dictatorship (1962-89), in search of a role model, beyond one’s own parents, I benefited hugely from listening to my own close relative, the Commissioner of Saggaing Division, the late U Zan Yin, in a series of conversations, recounting what Myanmar’s best known national martyr, Aung San, was like as a person, what motivated him to throw his lot in the anti-imperialist struggle against the British rule in colonial Burma, how the latter conducted himself among other students, what influenced him. Zan Yin and Aung San, the two young men from upper-Burma’s petty bourgeoisie families, were classmates in Pali studies, friends and next-door neighbours at Pegu Hall, Rangoon University in the mid-1930’s.

Those conversations about Aung San were among the stories and narratives which shaped my conception of a fine Burmese revolutionary and an intellectual who was head and shoulders above his peers and what it meant to pursue a life of service, over narrow self-interests.

Based on my long years of friendship and meaningful interactions, I can say with confidence Harn is cut from a different moral and spiritual fibre vis-à-vis other public figures with similarly “good pedigrees”, for instance, exiled children of former nationalist leaders such as Kyaw Nyein, Aung San, Nu, etc.

Aside from a crucial issue of leadership qualities essential for anyone in political affairs to succeed in public service, exiled and in-country, what sets Harn apart from other exiles and dissidents is his observance of the faith of his choice.

In these thirty years of working closely –whenever we have overlapping political priorities – with Harn, I have picked up on the deep spiritual influence of Christianity on him, a born Buddhist who converted to what we in Myanmar consider “an alien faith” only in his 20’s, living in his adopted Canadian city of Montreal.

Harn’s conversion was significant because his parents, who led the ruling house of Yawnghwe in Southern Shan State, were traditional patrons of Buddhism in Shan agrarian society. Granted that the hereditary rulers of Shan states, including Harn’s family, were forced to give up their privileges, including their royal titles, during the 1st un-declared coup disguised as The Caretaker Government of General Ne Win (1958-1960), societal attitudes and sentiments persisted.

In spite of the weight of the tradition, his exiled revolutionary mother, the late Mahadevi Sao Nang Hearn HKam, blessed him as Harn married into a Christian Canadian family in a church wedding.

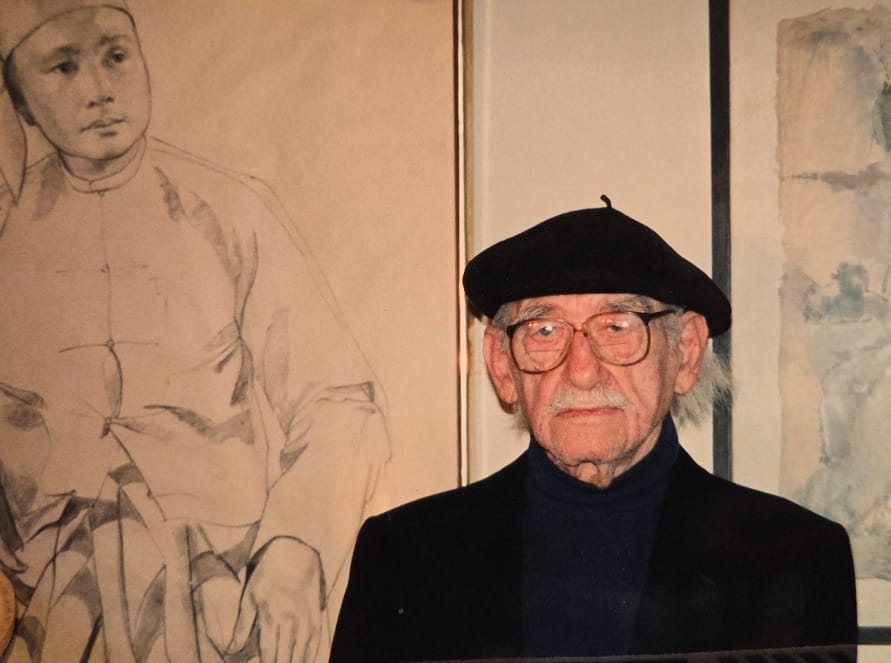

Louis Walinsky (1908-2002), in front of the portrait of his lifelong friend and the first Prime Minister of Burma, the late U NU, at home in Washington, DC, 1998 (Photo by Zarni)

A close mutual friend of Harn and I, the late Louis J. Walinsky once remarked to me, “you know Mahadevi showed a remarkable poise in accepting her son’s choice of faith (breaking with the family tradition).” The father of Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign manager and speechwriter Adam, Lou knew the Yawnghwe family, during his stay in Rangoon as the Economic Advisor in residence in the Union of Burma Government from 1953-1958)

In spite of his genuine belief in Christianity, Harn doesn’t wear his faith on his sleeves. But quietly, the faith guides his involvement in Myanmar politics in a positive way.

Certainly not in political meetings, policy briefings, or activist retreats which we both have been. There have been plenty of these occasions since we first became acquainted at a Burma event in New York City in 1996.

In the winter of 2019, I paid Harn a visit at his home in snowy, icy Montreal as I was on a short round of visits doing an oral history of the older generation of Burmese exiles, whose family lives were deeply intertwined with Myanmar’s political affairs. (The other two distinguished Burmese emigres whose live stories I had recorded are Bilal Rashid in Maryland and retired Professor U Kyaw Win in Colorado).

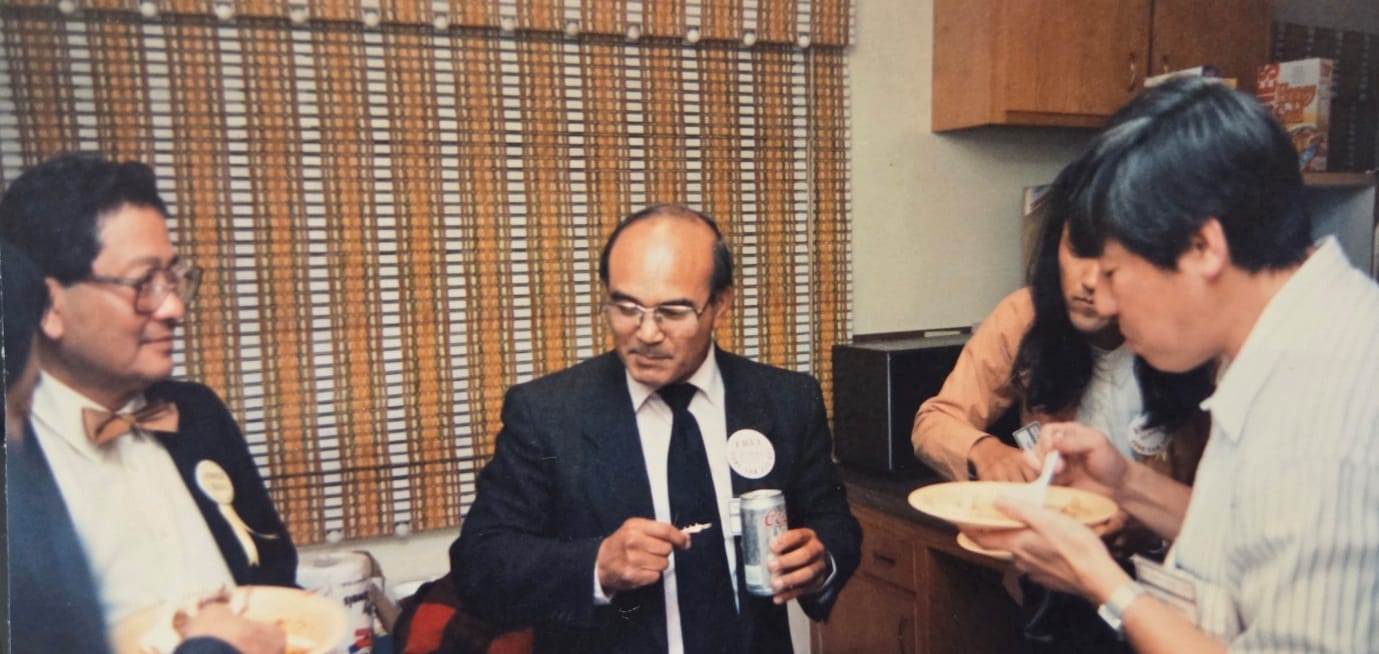

Myanmar exiles gathered for a meal after a Burma event in Los Angeles, California, 1992. From left to right: Professor U Kyaw Win, Dr Aung Khin (deceased), Coban Tun and Dr Kyaw Nyunt. (photo by Zarni)

Source: Why Myanmar’s Conflict Persists: An Interview with Sao Harn Yawnghwe, 10 Dec. 2025.

In our day-long conversation, Harn talked intimately about the importance of his Christian faith. A month ago, in his YouTube interview, in Myanmar language, with Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N), he was asked about personal trauma and pain of displacement and dispossession and his advocacy for dialogue with the much-reviled military leaders.

The interviewer Nang Seng Non asked if he had any resentment towards Myanmar military (leaders), and what motivated him to promote dialogue with them. He responded calmly:

“If I acted out of resentment, the cycle of revenge would never stop. Because of my faith, I leave judgment to God. My responsibility was to work for stability if dialogue could help.”

As I described in details, Harn was, naturally, afflicted with pains trauma and dark memories – of seeing the closest brother Sao Myee, under a sheet of white cloth, lying in a pool of blood who became the very first casualty of the military rule, the loss of the father who passed away in a solitary confinement in General Ne Win’s captivity, the loss of a family home in a prime location in Rangoon, the completely shattered life as a family who helped in the founding of a post-colonial multi-ethnic nation and the uprooted exile for more than half a century.

The impact of the trauma of having to flee one’s own country with the mother and two sisters in 1963 after the death of the politician father in Ne Win’s solitary confinement is lasting. I remember chatting with him over a quiet dinner one evening by Ping River in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, where Harn began his exilic years as a high school student. We were then talking about dissidents’ need to take safety seriously. He said, “you know I always carry my passport in my pocket.” It dawned on me that escape is his default position rooted in personal experience half-a-century ago.

Several months ago, I was having lunch with a small group of Ukrainian friends. At some point, our conversation touched on the subject of the Holodomor, Stalin’s policy of “death by hunger” in Ukraine, then a part of the USSR and the greatest grain producing republic of all Soviet republics. One of the Ukranians said, “my parents survived Stalin’s starvation in the 1930’s. When I was growing up, at home they never ate everything and always saved a little bit of food.”

Trauma is a common outcome of those who survive crimes of their states and countrymen. Exiles do reel from trauma. Aplenty. And I know. After nearly four decades away from my (now deceased) parents and seven other siblings and extended family members in our large clan in Mandalay. Their/our trauma differs in degree, not in kind, vis-à-vis the trauma and pain of those who remain trapped in repression in their country of birth.

During my short visits to Rangoon (from my hometown of Mandalay, 400-miles upcountry from the then capital) in those isolationist years of General Ne Win’s rule in the early 1980’s, I remember seeing the delipidated family residence in a large compound which once belonged to Harn’s family, from the window of a local bus I routinely took to get to my uncle’s home in Golden Valley where I usually stayed.

Once I asked Harn if the military ever returned the family estate. With a chuckle devoid of any resentment or bitterness, he said, “it’s now the site of the Pearl Condo. When I was staying in Rangoon (for ceasefire negotiations), I rented a flat there.” He said these words as a matter of factly.

To me, seemingly little things reveal a lot more about a person than grandiose pronouncements about God, Love, Faith, Vision etc.

Because I mentioned to him that I detected the influence of Christianity in the way he confronts the world, he emailed me a few biblical quotes, which he obvious lives by. Though not a believer myself, I appreciated them. Here is one that resonated with me.

“Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others.” — Philippians 2:3-4 (ESV)

Harn Yawnghwe, walking contemplatively among the mass graves at Sachsenhausen, the purpose-built Nazi concentration camp, on the outskirt of Berlin (with a group of anti-genocide Myanmar exiles who gathered at the Berlin Conference on Rohingya genocide, held at the Jewish Museum of Berlin), 27 Feb. 2018 (photo by Zarni)

During the military-led early reform years (2010-15), at the request of the then President and ex-General Thein Sein, Harn served as an advisor on inter-ethnic peace and played an instrumental role in facilitating a long series of ceasefire negotiations between the essential military’s stakeholders and representatives of the country’s ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), who had been waging a low-intensity war against the ruling military for federalist political autonomy for decades. This joint effort amongst different parties in conflict bore fruit with the signing of what came to be known as The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement” (or NCA) on 15 October 2015.

At the time, the Indian Defence Review offered a balance reading of the NCA: “(n)otwithstanding the shortcomings, the NCA is no mean achievement given the fact that it is the first of its kind in the history of the country. The coming together of a collective of the ethnic armed groups, the government of Myanmar as well as international actors to formulate the NCA signals the success of peaceful diplomacy.”

Harn correctly viewed the NCA under Thein Sein as a significant step in the right direction to bring the country’s civil war to a close, a war into which the country has plunged within 90-days of independence from Britain with the Burmese communist party declaring its armed revolt on 28 March 1948. For him, despite the non-participation of the two China-influenced Kachin Independence Organization and the United Wa State Army, the NCA explicitly recognized the civil war as a categorically political matter, that could only be resolved through political negotiations – as opposed to framing the country’s civil war as simply a technical matter that concern “military or national security” establishment.

These are two radically different framings of a single reality of brothers killing brothers while inhabiting a single national space.

Against the backdrop of Myanmar’s emerging political, administrative, geographic and commercial fragmentation ala Syria amidst the multi-front raging military conflict throughout the country, even the flawed political dialogue for nationwide ceasefire is better than no dialogue at all. That is, if the goal is long-term peace and political and ethnic reconciliation, particularly in a situation such as Myanmar’s where the Zero Sum victory or defeat is inconceivable for any group.

Myanmar’s larger issue: Faith and Politics vs Faith in Politics

Harn Yawnghwe, speaking in support of Myanmar’s persecuted Rohingya, an International Conference hosted by Hasene International, Cologne, Germany, 2 May 2018 (photo by Zarni)

The influence of faith (Buddhism in particular) in politics among Myanmar politicians is a well-documented phenomenon, with the late Prime U Nu and Aung San Suu Kyi being two best known cases.

However, upon closer look, one cannot fail to notice that the two most influential Bama or Burmese politicians appear to have talked the talk but did not really walk the walk.

In the case of the late U Nu, who was best known for his propagation of Buddhism and incessant talk of Buddhist meditation, Nu failed to approach the country’s most contentious issue of ethnic equality, using Buddhist-influenced conceptions of fairness, justice and equality, the conceptions that are not alien imports from the liberal West. In his biography entitled Saturday Sun (Yale University Press, 1975) translated and edited by two famous exiles, the Nation’s Chief-Editor Edward Law Yone and Professor Kyaw Win, U Nu talked about how he was engaged in loving kindness meditation to try to hasten, psychically sending the power of Metta or universal loving kindness, as we say in Burmese, the end of the undeclared American War in Vietnam, and yet he was bitterly opposed to recognizing the right of self-determination of the country’s non-Bama ethnic people!

Successive generations of the mainstream Buddhist Bama nationalists, both military leaders and parliamentarians, reneged on one of the two founding principles of post-colonial sovereign Union of Burma, namely ethnic group equality and the right to self-determination. The first driver behind Myanmar’s political conflict and the ensuing civil war, which began in March 1948, was the scramble for power among the Burmese communists and their former revolutionary comrades with non-communist orientations. The second trigger for the subsequent waves of armed revolts was the betrayal of the principle of ethnic equality or “federalist power sharing”, between the dominant ethnic Bama on one hand and the rest of the non-Bama ethnic groups on the other.

Similarly, Aung San Suu Kyi did not address this contentious issue of ethnic equality any more satisfactorily than the late Prime Minister U Nu (ousted in 1962 military coup), who was her father’s deputy at the time of his assassination in 1947. Her spectacular failure in standing up for Rohingya victims of Myanmar military’s genocide destroyed the international good-will towards Myanmar and her tremendous moral standing in the world. Dubbed “the most enlightened woman” by a former Buddhist monk from USA, Aung San Suu Kyi would sprinkle her political narratives with Buddhist vocabularies, but when push comes to shove, she chose not to extend her Buddhist notions of universal kindness or compassion to the genocided Rohingya Muslims.

While flying thousands of miles to the Far East, Australia, Europe and N. America to dine and wine with heads of states, queens and kings and politicians of all stripes and colours she didn’t bother taking one hour helicopter ride to visit Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazaar, across the boundary river Tek Naf, during her years as the de facto head of state. That, in spite of the then PM Sheik Hasina’s personal invitation, when the two powerful daughters of the martyred national leaders, met at a conference in Asia.

From Montreal, Canada, Harn took the trouble to go and bear witness to the post-genocidal conditions in which Myanmar’s Rohingya people exist, accompanied by Suu Kyi’s old friend Professor Kyaw Win of Colorado, USA, who is a Karen Christian.

It is one thing that individual politicians and activists are guided by their faith and spirituality, but it is entirely a different – and destructive – matter where they seek to openly mix their individual faith with matters of states and policies.

Ninety years ago, the emerging young anti-imperialist leaders of the premier colonial era Rangoon University had their own individual faiths, and yet they banded together as “brothers” for a cause larger than their personal ambitions and spiritual preferences. This old grainy photograph embodies what was possible and what still is possible for a multi-faith nation such as Myanmar. Aung San was a secular humanist with strong Marxist-Leninist revolutionary orientation. U Nu was a superstitious traditional Buddhist. MA Rashid, with ancestral root in Allahabad, British India, was a Muslim. They held each other with basic respect and genuine appreciation.

Source: Bilal M. Rashid, The Invisible Patriot: Reminiscences of Burma’s Freedom Movement (Bethesda, MD, 2015)

In that regard the country’s two most influential politicians since independence – the late U Nu and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi –deviated from a healthy approach to nation-building in a naturally multi-faith society of majoritarian Buddhists and sizeable segments of Christians and Muslims.

U Nu used Buddhism as his electoral plank: offering to make the predominant faith of the country “official” or “state faith” to get the majority’s votes which, in turn, significantly alienated non-Buddhist communities such as majority Baptist Christian Kachin and Chin communities.

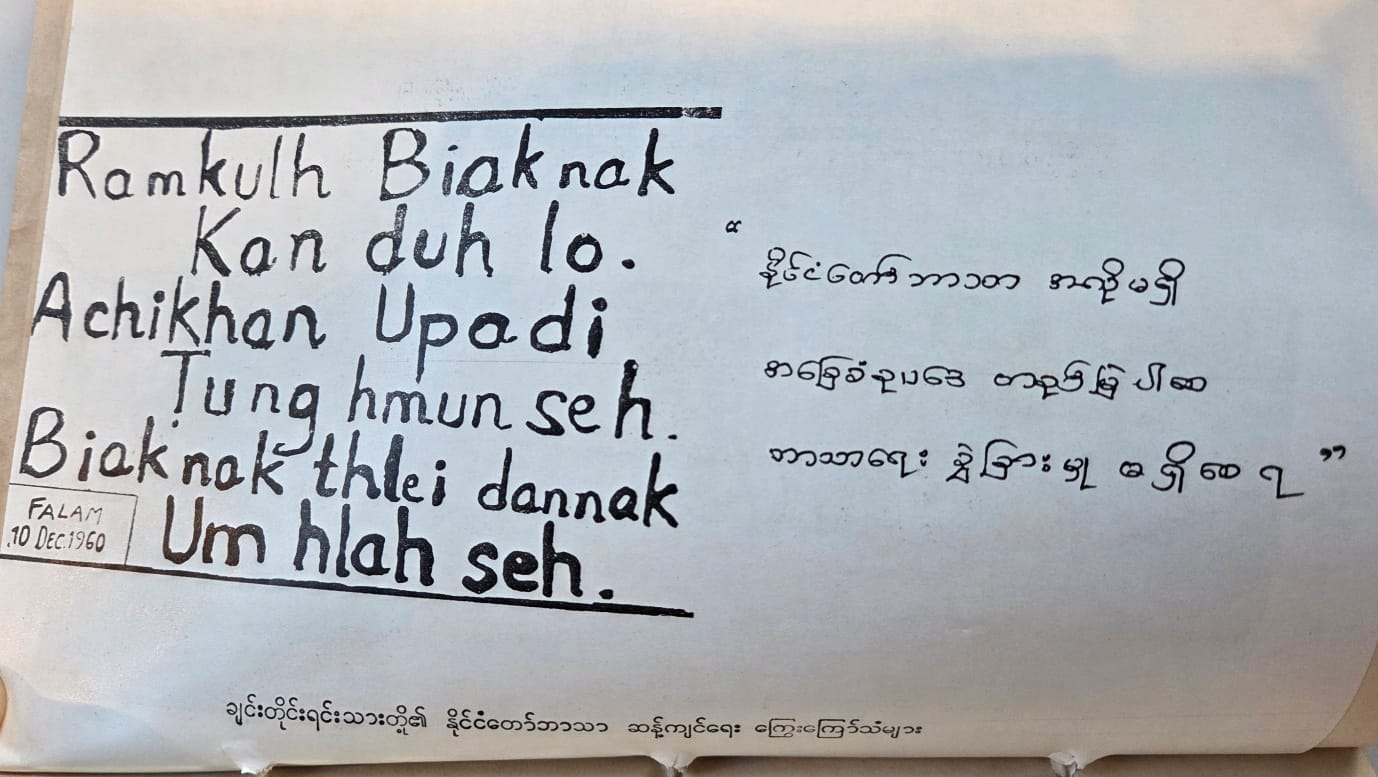

“We want no state religion. Long Live the Constitution of the Union of Burma. No religious discrimination.” are Chin People’s anti-state region slogans, Falam City, Chin State, 10 Dec. 1960.

Source: Myanmar Politics (1958-62). Volume III, Universities Press of Myanmar, 1991. P. 113.

Instead of providing Myanmar’s adoring public with a clear moral and intellectual leadership at a time the ruling junta of State Peace and Development Council was mobilizing Islamophobia via its proxies within the Buddhist Order to dilute and divert popular demand for democratic reforms, Aung San Suu Kyi stupidly opted to first keep studied silence and subsequently defended Myanmar military against genocide allegations. Instead of seeking to educate the public on the dangers of Islamophobia and racism, she swam downstream with the rising state-peddled racism against Muslims and Rohingyas. To placate Islamophobia, she chose not to field any Muslim candidate for her flagship opposition party National League for Democracy in the 2015 general election.

In both cases, the results were catastrophic with inter-generational consequences for Myanmar: Christian Kachin eventually resorted to open armed revolt, which to date continues; Rohingyas and other Muslims became victims of a textbook genocide and Islamophobic violence and further marginalization in Myanmar; and Myanmar as a UN member state, being confronted with genocide allegations at the International Court of Justice; and the anti-junta resistance movement with imprisoned Aung San Suu Kyi as its poster leader reels from little or no global support.

One of the reasons I hold Harn in high regards is the fact that despite his genuine devotion to his chosen faith of Christianity, Harn has kept his faith at a healthy distance from his policy advocacy and activist working meetings.

As “a secondary funder,” leading the longest-running Burma-focused political NGO run by a native Myanmar, he holds considerable influence in many an activist and resistance circles for the last three decades since the Euro-Burma office has been in operation. And yet he has shown remarkable capacity to avoid any type of discrimination based on faith or ethnicity. You would not even know that he is a Christian working to help end the vicious cycle of state violence, racism, and ethnicity-driven conflicts that have plagued our predominantly Buddhist nation. He has lent his support and cooperation in good faith, be they “the good soldiers” in the ruling military circles or the leaders of the armed resistance movements.

In the next section, I will turn to the mainstreaming of a non-ethnic Bama political exile into Aung San Suu Kyi-led pro-democracy opposition.

Harn and Government in exile, the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma

“(George) Soros was impressed with Harn. He wanted him (Harn) to head the Burma Project he was starting, but I wanted to keep Harn for our exile Government,” said the mathematician-turn-Member-of-the-Parliament-elect Dr Sein Win. U Ba Win, his father was General Aung San’s older brother who also served as a member of pre-independence cabinet of the Government of Burma which Aung San headed.

Dr Sein Win and I were chatting in his office in Washington, DC in the late 1990’s. In those days, as a student activist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, involved in Free Burma boycott and divestment campaigns, I made short and frequent visits to Washington DC to touch base with the leaders of the exile government and for political lobbying on US policy on Burma.

As Dr Sein Win put it, “the old man was ready to give us money. We didn’t even have a bank account then!”

From left to right: Professor Kyaw Win (90), Dr Vum Sum (deceased), Naw May OO, Dr Chao Tzang Yawnghwe, with sunglasses (deceased), Dr Sein Win (Aung San Suu Kyi’s cousin and head of the exile government), our American retreat facilitator, Dr Marjolaine Law Yone, , (deceased), Professor Maran Law Raw, Dr Thaung Tun, Dr Zaw Oo, Dr Kyi May Kaung, Harn Yawnghe and Maung Zarni, Political Exiles’ Retreat, Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, Feb. 1999.

Harn travelled to New York in order to assist and accompany the newly arrived Burmese political exile to the latter’s meeting with the billionaire philanthropist in his office in Manhattan.

A brief detour here on Harn and his background.

With an unassuming but self-assured personality, Harn comes with an impressive professional background: he was initially educated as a civil engineer at Chulalongkorn, Thailand’s top university, earned his MBA from McGill in Montreal where he settled as a political refugee in the late 1960’s, and worked as a finance advisor to President of a major Thai bank in Bangkok before moving on to work in finance in the then British-controlled Hong Kong.

He was then already a well-known Canada-based exile. I knew him by reputation: he circulated Burma Alerts, a compilation of Burma news updates, amongst the Burmese diaspora and those with an interest in Burma. In the pre-Internet days, the hard copies of the updates had to be posted to those who subscribed to the alerts. In fact, I knew his older brother Eugene (see the photo below) before I knew Harn, as early as 1991. We were both doing our PhDs studying authoritarian regimes, particularly Myanmar’s military dictatorship at two different N. American universities. I stayed with Eugene in Vancouver, British Columbia in Canada when we both read our research papers on Burma at a regional conference on Southeast Asia. A deep and radical thinker, he nurtured me intellectually through our regular postal correspondence before the Internet became the primary medium of communications. In those days, I was still soaked in Bama Buddhist chauvinism, having been raised in a nationalist, militarist social circle.

Both Harn and his late brother, a devout Christian and a Marxist radical thinker, handled themselves with modesty and humility, and treated others, young or old, with basic respect and decency, in spite of the fact that they were manor-born.

It was a rare personal quality among the neo-feudal social circles of Myanmar diaspora, which I admire most in my friendship with both.

Harn’s older brother the late Dr Chao Tzang Yawnghwe (known as Eugune Thaike, among my late parents’ generation who went to university in the late 1950’s), a Marxist-influenced scholar of comparative politics and former commander of the Shan State Army or SSA), speaking at the Free Burma Coalition conference, American University, Washington, DC, 2003 (photo by Zarni)

Nonetheless, the fact that Harn was a son of the late 1st President of the now defunct Union of Burma and a born prince, was a huge bonus for the exile government at the time. In politics, whether in a liberal democracy with advanced industrial economy, or formerly colonial and neo-feudal agrarian societies, pedigrees do matter. Google Nehru, Kennedy, Bush, Bhutto, Sukarno, and a long list.

The anti-junta opposition, both on the ground and underground inside Burma, as well as in the diaspora, were only happy to have dissidents with famous family names leading the fight.

To Soros, Harn was an ideal managerial candidate for his new Burma Project, out of the then Open Society Institute (later Open Society Foundations).

To Dr Sein Win, Harn was crucial to grow the nascent exile government into an influential political lobby, in western capitals, which, unlike today’s Trumpian West, gave a damn about democracy and human rights at the time.

What neither of them seem to understand is Harn was, and has always been, his own man.

As mentioned in the 1st part of this long semi-biographical essay on Harn, his Shan family was steep in federalist politics pre-1962 coup, and the Shan revolutionary movements which sprang up after the coup. The country’s successive military leaderships – or for that matter, the dominant ethnic Bama or Burmese political and intellectual elite had never really understood, appreciated or bought into the idea of ethnic group equality and the attendant political right to self-determination.

The martyred Aung San was officially and popularly portrayed as “the sole founder” of modern Burma, while ignoring the objective fact that there were other co-founders of the post-colonial or independent Burma, drawn from other non-dominant ethnic groups. This is something which Aung San Suu Kyi has internalized: my father founded Modern Burma and I bear his mantle as my father’s daughter. There was an easily detectible sense of entitlement and personal destiny in the way she had pursued national politics, which tragically ended with the coup of 2021.

Blinded by the mainstream ethnic Bama elite’s mistrust of the hill (read “backward”) peoples as tribes “bent on seceding from the new modern state, post-Aung San political elite of Burma, the Bama majority both civilian and soldiers, falsely viewed federalist thoughts and principles as a step towards secession (or “the break-up of “our small country between the two giant neighbours of China and India and Thailand as USA’s proxy). Little did the political and intellectual class of Bama understand that the Federalist movement Harn’s father was leading was to revive the original pre-independence vision of Burma as a federated union, a union based on voluntary association and anchored in the principle of ethnic group equality and self-determination.

In the previous section, I made a mention about Harn’s family friend the late Lou Walinsky, resident economic advisor to the Union of Burma Government (1953-58). In his retirement in Washington, Lou was in occasional correspondence with Harn’s exiled mother, the Mahadevi in Alberta, Canada. The main subject was the sordid affairs of Burma. After his passing, Lou family tasked me with sorting out his Burma papers for the Southeast Asia Collections at Cornell University, his alma mater. In going through Lou’s files, I stumbled upon one hand-written letter by Harn’s mother in Canada which had immense historical value.

In that letter, the exiled Mahadevi stressed that “it was (General) Aung San who volunteered to include the right of secession for non-Bama ethnic people who were present at Panglong Conference.” Besides the emerging broader political situation concerning Britain’s lukewarm stance towards demands for ethnic equality – after all the British rule was typically built on ethnic and religious divisions in any part of the world where London built its empire – that Aung San’s straightforward and honest character made a very favourable impression on the non-Bama representatives.

Here by ethnic self-determination (and the right of secession), she was referring to the Constitutional right of secession, based on the promise of the historic Panglong Conference of 1947 which produced what in effect was the blueprint for the independent Union of Burma. the blueprint in terms of the voluntary association of different ethnic groups to form a post-British sovereign nation-state.

The document which came to be known as The Panglong Treaty, was signed by a group of leading representatives from Kachin, Bama, Shan, and Chin groups, including her late husband Sao Shwe Thaike and Aung San Suu Kyi’s father the martyred general Aung San,12 February 1947.

Myanmar’s constitution specifically granted Kachin, and Shan people the right of secession after the initial period of 10 years from independence should the voluntary association failed to meet their political and administrative aspirations.

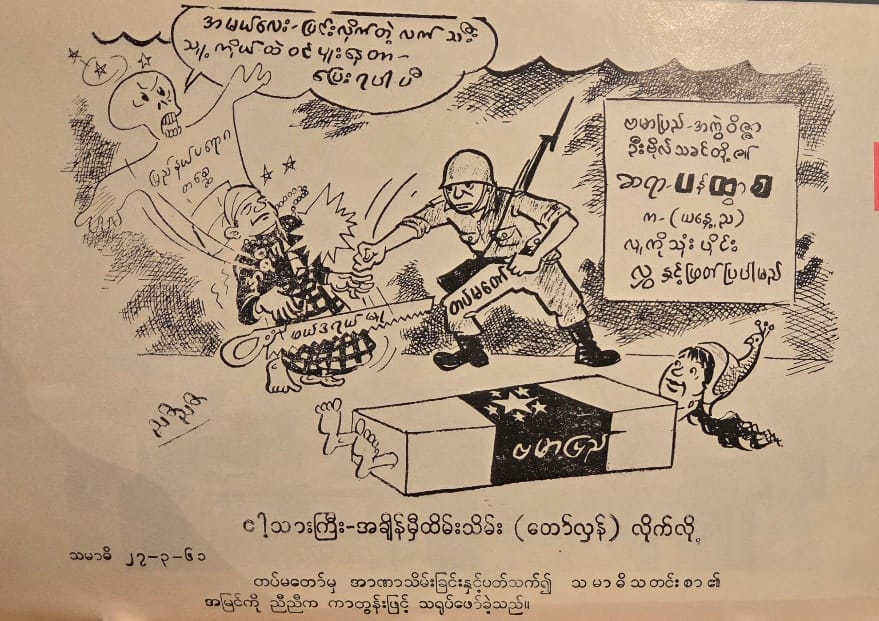

This political cartoon in the publication Ahtauk-taw (dated 21 Oct. 1961), paints a Shan hereditary leader as being deceptive, implying that the Shan federalists were operating behind the façade of the narrative of Federalist Seminar held in Southern Shan State Capital Taung Gyi while their real intent was secession through armed revolt.

Source: Myanmar Politics (1958-1962), Volume 4, Universities Press of Myanmar, 1991), p. 210.

One little known fact in Myanmar affairs needs to be stressed here: after the death of Aung San, the architect of Burma as “a federated union”, Bama ethnic political elite, made up of parliamentarians led by PM U Nu and the Tatmadaw (or the armed forces) (as well as intelligentsia), conspired to pre-empt this constitutional right to self-determination, particularly by the Shan leaders with control over the largest constituent state of the Union. In the fall of 1994, in Sterling, Virgina, USA, I interviewed the retired Colonel Chit Myaing and former Burmese Ambassador to UK, who served as a member of General Ne Win’s 1962 coup cabinet, The Revolutionary Council for nearly 10 hours with only lunch and rest room breaks. He said that the Defence Services Academy whose officer corps today rule Myanmar was founded in a new purpose-built town named Ba Htoo, in Shan State as a strategic military base. The Prime Minister U Nu presided over the establishment of the DSA in the early 1950’s.

The greatest irony is that the Bama elite’s paranoia about the other ethnic groups’ right to self-determination became self-fulfilling. Triggered by the anti-federalist coup of 1962, non-violence Shan politicians went underground and set up Shan State War Council which was headed by Harn’s mother Mahadevi, and united and strengthen a few armed organizations, into Shan State Army (SSA), in 1963. Six decades since the coup of 1962, virtually all ethnic communities, including Rohingyas, of Myanmar now have their own armed organizations. It certainly doesn’t bode well for peace in Myanmar.

Harn’s entry into the exile government circle was, for this single reason alone, for better. For it inevitably reinjected the original idea of federalizing Burmese politics, including the democratic opposition.

The absence of a national political framework grounded in ethnic group equality, that can adequately address respective sets of very real grievances among different ethnic communities has been an Archille’s heel for the country. The country’s trapped in the vicious cycle of coups and quasi-democratic elections that fail to resolve long-standing political problems though political means.

Source: Myanmar Politics (1958-1962), Volume 4, Universities Press of Myanmar, 1991), p. 210.

A Burma Day, a policy discussion, hosted by the EU External Affairs Division, EU, Brussels, 2001 (Photo in Zarni’s files)

The three Burmese exiles sharing a lighter moment, the Burma Day event, 2001 (photo in Zarni’s file).

Using his formidable managerial skills, Harn wrote funding and political proposals to various sympathetic governments and INGOs on behalf of the exile , sought to systematize the Washington-based exile government’s organizational and budgetary matters, set up a management team to run the Oslo-based Democratic Voice of Burma, set up after Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize helped exiled MP-elects, scattered in the United States and Thai-Burmese border regions with their strategic meetings, drafted speeches and briefing notes for Dr Sein Win, and accompanied him to important policy meetings.

Among the Burmese diaspora, Dr Sein Win was well-liked and well-respected for his honesty, simplicity and unassuming personality. But the exiled Bama leader, in due course, proved rather ineffectual and uninspiring. Whatever his shortcoming as an accidental revolutionary, with the benefit of the hindsight, his judgement to bring on board Harn as his chief advisor and organizational builder of the exiled government was spot on.

The exile government led by Aung San Suu Kyi’s cousin Dr Sein Win had long folded as Aung San Suu Kyi became the most important political player after her release from the last house arrest in November 2008. For years, he was serving as an unofficial representative for his cousin, on and off under house in the 1990’s.

Harn had also pivoted from supporting Dr Sein Win’s Burmese exile government towards building up the Euro-Burma Office, initially operationally based in Brussels.

Since the nationwide uprisings of 1988 which forced the Burmese military dictator General Ne Win to formally relinquish power the exilic political activism has been a growth phenomenon. Many an exiled organizations have sprung up in different parts of the world with varying degrees of success.

No pro-democracy political NGO based in the West has proven more professional, financially sustained and politically credible in international policy circles than the Euro-Burma Office (EBO). Harn set up EBO’s mother outfit in Canada, Associates to Develop Democratic Burma Inc. (ADDB, Inc.) as early as 1990. He has been running EBO as its operational venue since he left the exile government.

At times, I wondered if Harn should have worked for the deep-pocketed George Soros, running his newly established Burma Project, out of the then Open Society Institute (later Open Society Foundations). One major positive would be there would be no need him to stress about fundraising. As a politically independent organization, Harn does need to keep the EBO and its civil society and other political initiatives afloat through various philanthropic and governmental agencies in Europe.

But then again, Harn would have been a Soros’ employee or staff, however well-paid and financially stress free.

As is customary with Myanmar political circles, if a person is doing well, or advocates certain unpopular ideas, gossip mills generate slanderous rumours about a person’s character. The standard mudslinging involves finances – how they are managed, whether they are embezzled or misused or where the funding comes from.

Over the years the rumour mill has spread baseless accusations about EBO finances, Harn’s “luxurious” or “business class flights”, etc. Additionally, Harn has been portrayed as “an appeaser” or “a collaborator” with the successive military leaderships.

Dr Kyi May Kaung, a US-based former Burmese academic, poet and writer from a highly reputable Sino-Burmese family in Rangoon, emailed me and expressed her disgust that the Burmese who don’t really know Harn would question his personal integrity in handling finances. She moved in Rangoon’s cultural and intellectual elite circles in the pre-1962 coup years, and was very well-acquainted with Harn while both of them were assisting the exile government in Washington, DC.

Both Harn and I have publicly defended Rohingya people as they came under society-wide racism, long before the 2017 genocidal violence.

As a matter of fact, Harn was the first Myanmar public figure who was personally involved in helping to establish the Arakan Rohingya Union in Jedda, Saudi Arabia in 2011. EBO has long supported as a matter of organizational priority, the struggle for ethnic equality including the equality of Rohingya people in their own ancestral home of Western Myanmar. Because Rohingyas have been falsely framed as illegal “Muslim Bengalis” anyone or group that stands up for them is often subject to accusations of being in the pocket of “rich Muslim Arab governments” and the OIC.

Neither Harn nor I consider these rumours and personal slanders serious enough to respond.

I have been in many a Burma retreats, meetings and events with Harn, from western capitals to Southeast Asia’s capitals. Several years ago, we were travelling to Jakarta, Indonesia for a government hosted consultation meeting on the political developments in Myanmar. It so happened that we were catching the same connecting flight in Doha, he is coming from Montreal and I, from London Heathrow.

As I walked through the aisle to get to my Economy seat, I spotted him in the same Economy cabin, looking exhausted, in his early 70’s already, after a long haul flight from Canada to Qatar. We still had another 11 or 12 hrs to go.

Harn does these long-haul flights between his home city in Montreal and various Southeast Asian destinations quite frequently.

I told myself, “What dedication!”

Many of his contemporaries in exile have long bowed out of exilic activism on Myanmar, for various reasons, personal and political. Apparently, Harn has not given up.

In his 10 December 2025 interview with S.H.A.N, he told his interviewer Nang Seng No asked if he saw Myanmar changing for the better, “I don’t know if things will improve in my lifetime. But I hope the younger generation will carry on and find the solution. The public sees nothing good in the military, and that may be true. But I believe there are good people within the military. To them, I say this: If you truly care for the country, you must act. Do not let Myanmar fall further behind its neighbours. If this crisis continues, it will not only destroy the public—it will destroy the nation.”

Wise and heart-felt words.

Will the public, the resistance groups, the ruling military leaders heed them?

Ethno-supremacy of the dominant Bama, Burmese or Myanmar

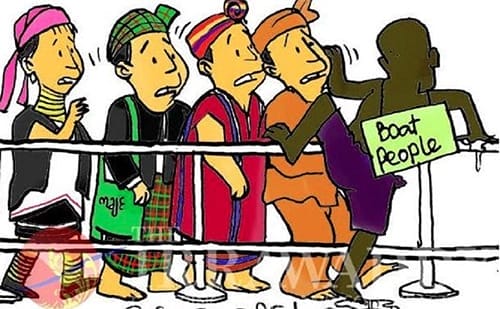

Myanmar’s pro-democracy intelligentsia including journalists supported the military’s genocide against Rohingya people, falsely portraying the victims as “illegal aliens”. Amidst the genocidal campaign in Rakhine State, Western Myanmar, the influential Irrawaddy News with millions of Myanmar followers published multiple news reports and cartoons such as these two.

Myanmar politics has been afflicted not simply with the political violence perpetrated by the successive military regimes, but also with what I consider internal colonialist ethno-racism of the dominant Bama. This continues a political plague even today with loyal followers of Aung San Suu Kyi, who now lead the National Unity Government of Myanmar and the National Unity Consultative Council, established after the 2011 coup.

Back to Harn’s joining the now defunct NCGUB, or the exile government, as its advisor.

Because of his Shan ethnicity, and the family’s legacy of advocating for genuine Federalism, many a Burmese politicians, activists and academics see him primarily through the prism of ethnicity. A well-known Burmese political scientist from my hometown of Mandalay who went on to serve as Thein Sein’s presidential advisor on Rohingya affairs, once asked me at a Burma Studies academic conference, “Ahko (older brother), do you trust Harn Yawnghwe? I don’t.”

Even some within the exile government harboured resentment towards Harn, on account of his ethnicity. The sentiment was: why was an ethnic Shan exile having an oversized role in the Burmese exile government headed by a son of a Bama martyr?

Accordingly, I was even urged to go and work for the DC-based Burmese exile government headed by Dr Sein Win.

In diaspora or inside Myanmar, we Myanmar have proven ourselves incapable of seeing beyond ethnicity and faith of political actors. U Nu and his deputies made a devastatingly consequential mistake when they replaced the young independent country’s Commander-in-Chief, a highly decorated professional General Smith Dunn, with the (Fascist Japanese military intelligence) Kempeitai-trained Colonel Ne Win in January 1949, on account of Dunn’s Karen ethnicity (and Christian faith). For the Bama elite’s ethno-paranoia blinded them to the fact that Smith Dunn was trained as a soldier in a parliamentary democratic tradition of England where elected politicians make defence policies and do the hiring and firing of commanders, not the other way around.

In Harn’s case, what was overlooked was Harn brought to the exile government circle his exilic international experiences, first hand understanding of interethnic political dynamics, managerial skills, a sharp mind and personal integrity.

After reading the 1st part of the semi-biographic essays on Harn, Dr Helen Jarvis, the Cambodia-based former Australian academic and the founding head of the Public Affairs department at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal wrote me a note saying that she remembered meeting Harn some years ago, and characterized him as “a quiet but determined person” (on Myanmar political affairs).

Though a Shan ethnically and a Christian by faith, Harn’s political involvement in Myanmar affairs, in the diaspora, among armed organizations and in the Thein Sein government-led ceasefire processes, is not anchored in his Shan-ness or Christianity. He is involved in Myanmar’s politics because he genuinely cares about the welfare of the people as a whole and the country’s future. I have been to so many policy briefings, activist retreats, international conferences and a Track II meeting with Myanmar’s military representative in the last 20-odd years. Never have I had an impression that Harn privileges any mono-ethnic causes above the nation’s need for the cessation of all-around hostilities, killings and violence and for peace and reconciliation.

In the third and final section of my semi-biographic essay on this remarkable son of Myanmar, I will discuss both the larger geopolitical and ideological context in which the exilic activism, revolutionary or conservative, has been pursued and the need to document our national history with intellectual honesty, by countering ethnonationalist tendencies to erase those who are not part of the dominant ethnicity or majoritarian faith-based group.

________________________________________________________

READ: PART 1 – PART 3

A Buddhist humanist from Burma (Myanmar), Maung Zarni, nominated for the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize, is a member of the TRANSCEND Media Service Editorial Committee, of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, former Visiting Lecturer with Harvard Medical School, specializing in racism and violence in Burma and Sri Lanka, and Non-resident Scholar in Genocide Studies with Documentation Center – Cambodia. Zarni is the co-founder of FORSEA, a grass-roots organization of Southeast Asian human rights defenders, coordinator for Strategic Affairs for Free Rohingya Coalition, and an adviser to the European Centre for the Study of Extremism, Cambridge. Zarni holds a PhD (U Wisconsin at Madison) and a MA (U California), and has held various teaching, research and visiting fellowships at the universities in Asia, Europe and USA including Oxford, LSE, UCL Institute of Education, National-Louis, Malaya, and Brunei. He is the recipient of the “Cultivation of Harmony” award from the Parliament of the World’s Religions (2015). His analyses have appeared in leading newspapers including the New York Times, The Guardian and the Times. Among his academic publications on Rohingya genocide are The Slow-Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingyas (Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal), An Evolution of Rohingya Persecution in Myanmar: From Strategic Embrace to Genocide, (Middle East Institute, American University), and Myanmar’s State-directed Persecution of Rohingyas and Other Muslims (Brown World Affairs Journal). He co-authored, with Natalie Brinham, Essays on Myanmar Genocide.

A Buddhist humanist from Burma (Myanmar), Maung Zarni, nominated for the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize, is a member of the TRANSCEND Media Service Editorial Committee, of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, former Visiting Lecturer with Harvard Medical School, specializing in racism and violence in Burma and Sri Lanka, and Non-resident Scholar in Genocide Studies with Documentation Center – Cambodia. Zarni is the co-founder of FORSEA, a grass-roots organization of Southeast Asian human rights defenders, coordinator for Strategic Affairs for Free Rohingya Coalition, and an adviser to the European Centre for the Study of Extremism, Cambridge. Zarni holds a PhD (U Wisconsin at Madison) and a MA (U California), and has held various teaching, research and visiting fellowships at the universities in Asia, Europe and USA including Oxford, LSE, UCL Institute of Education, National-Louis, Malaya, and Brunei. He is the recipient of the “Cultivation of Harmony” award from the Parliament of the World’s Religions (2015). His analyses have appeared in leading newspapers including the New York Times, The Guardian and the Times. Among his academic publications on Rohingya genocide are The Slow-Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingyas (Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal), An Evolution of Rohingya Persecution in Myanmar: From Strategic Embrace to Genocide, (Middle East Institute, American University), and Myanmar’s State-directed Persecution of Rohingyas and Other Muslims (Brown World Affairs Journal). He co-authored, with Natalie Brinham, Essays on Myanmar Genocide.

Tags: Burma/Myanmar, History

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.