The War at Home

ANGLO AMERICA, 18 Aug 2025

David Cole | The Nation - TRANSCEND Media Service

Red Scares in the US Past and Present

15 Apr 2025 – The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” So begins L.P. Hartley’s masterful novel of love and memory, The Go-Between. The line might serve as a motto for historians. The historian’s challenge is to understand just how different an earlier period of human existence was, and to resist drawing parallels with contemporary times.

Clay Risen’s Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America remains true to this principle. Providing a wealth of engaging detail that underscores how different the mid-20th century was from today, he tells his subject’s riveting and shameful story from its origins after World War II to its demise in the late 1950s. And he expressly declines to draw analogies to the current moment.

That may have been easier to do because he wrote Red Scare before the reelection of Donald Trump and the train wreck that is already Trump 2.0. But even if he studiously avoids delineating the similarities, for anyone reading it now the parallels are too stark to ignore. Because it shows how populist scapegoating can take hold of a nation and pose real dilemmas for the many who get caught in its web, Red Scare is essential reading today.

There have actually been multiple Red Scares in American history. The first one, which began shortly after World War I, featured most prominently the Palmer Raids, in which the federal government responded to a series of bombings by rounding up thousands of foreign nationals and deporting more than 500 for their suspected associations with anarchist or communist groups. The roots of many anti-communist laws, in fact, date back to that period. That Red Scare ended in 1920.

The second Red Scare, the subject of Risen’s account, emerged almost as soon as World War II ended. Winston Churchill was one of the first to predict the Cold War in a speech he delivered in Missouri in 1946. That war quickly came home, taking root in Hollywood four months later, when the founding editor of The Hollywood Reporter, Billy Wilkerson, published the names of 11 suspected communists in Hollywood’s ranks. Others promptly joined in the call to rid Hollywood of reds, including Ronald Reagan and the novelist Ayn Rand. The House Un-American Activities Committee, born in 1938 out of a committee that investigated Nazis, turned its attention to communists and soon subpoenaed countless writers, directors, and actors to testify about their alleged ties to the Communist Party.

By 1947, President Harry Truman had announced a “loyalty program” for federal employees. The program, which reviewed the background of every current and new federal employee, screened 4.76 million people over five years, searching for “any evidence of ‘disloyalty,’ a term that was left ominously undefined,” Risen writes. Truman also directed his attorney general, Tom Clark, to compile a list of “subversive organizations,” which eventually included hundreds of groups, including the National Lawyers Guild, a progressive lawyers’ organization. Association with any group on the list could land you in an FBI file or cost you your job. Most people survived the Truman loyalty screens, but nearly 7,000 people resigned or withdrew their applications, and 560 were fired. The loyalty program discovered not a single spy.

Prominent trials of alleged communist spies Alger Hiss and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg divided the country—and ended in convictions of all three and the death penalty for the Rosenbergs. Congress passed laws making it a deportable offense and a crime to be a member of the Communist Party or to advocate its positions, and countless foreign nationals were deported and citizens convicted for their political beliefs.

At its height, virtually every part of society was in on the project. Congress enacted anti-communist laws and held hearings to reveal communist sympathizers and fellow travelers. Federal prosecutors tried people for their association with the party and for refusing to name names. The courts, including the Supreme Court, upheld the convictions. The FBI developed extensive files on suspected reds, including many Americans who simply advocated for racial justice or workers’ rights. Hollywood, universities, and other private organizations cooperated in the suppression, barring suspected communists from their employ.

State governments extended the scheme to the local level, enacting their own loyalty oaths and anti-subversive laws. Chicago barred suspected communists from public housing; New York State denied fishing licenses to members of any group on the attorney general’s subversive organizations list, and New York City fired even high school math teachers for suspected communist ties.

The parallels to what is happening today are hard to miss. Consider, for example, the origins of the Red Scare. Risen attributes it to a backlash against the New Deal, further fueled by the fear of a nuclear-armed communist adversary in the Soviet Union. The New Deal, he writes, had upended the old order and ushered in, albeit tentatively, “a new America—egalitarian, diverse, tolerant.” But not everyone was on board. Businessmen objected to regulations that protected consumers and workers, as well as to the higher taxes needed to fund a bigger government. And then, as now, the resentment extended far beyond the wealthy:

The progressives of the 1930s claimed to stand up for the Forgotten Man, but there were many Americans who felt that the New Deal had in fact forgotten them: the small-town middle class, the religious fundamentalists, the avowed white supremacists who continued to insist that America was a country founded by and for northern Europeans. They saw an America that was increasingly urban and cosmopolitan, industrialized and regulated, diverse and tolerant, run by what they believed was a detached elite unsympathetic to the average white American.

In a fundamental sense, the right is still fighting the New Deal, and it’s using a very similar strategy—one that stokes the grievances of Americans who believe they have been left behind by economic and cultural developments and are eager to find fault in elites and migrants. It is for this reason that, while most Americans are uncomfortable with the irresponsible haste with which Trump, with the help of Elon Musk, began tearing down the federal infrastructure that many rely on, his core supporters are not all that troubled.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s majority, composed of six Republican-nominated justices, espouses a deep skepticism about the administrative state. Last year, it overturned a 40-year-old precedent that required courts to defer to the expertise of agencies. And it has increasingly insisted that the president must have unchecked authority to remove any executive branch official he wants for any reason, calling into question measures that safeguard the independence of government agencies. In May, the court signaled in a temporary ruling that it is likely to overturn a 1935 precedent that permits Congress to rein in the President’s ability to fire the heads of independent agencies absent malfeasance or neglect.

And where New Deal progressives prized expertise and science as the basis for solving social problems, Trump has aggressively sought to suppress any evidence or research that might contradict his ideological commitments—including, most catastrophically, critical research on healthcare and climate change.

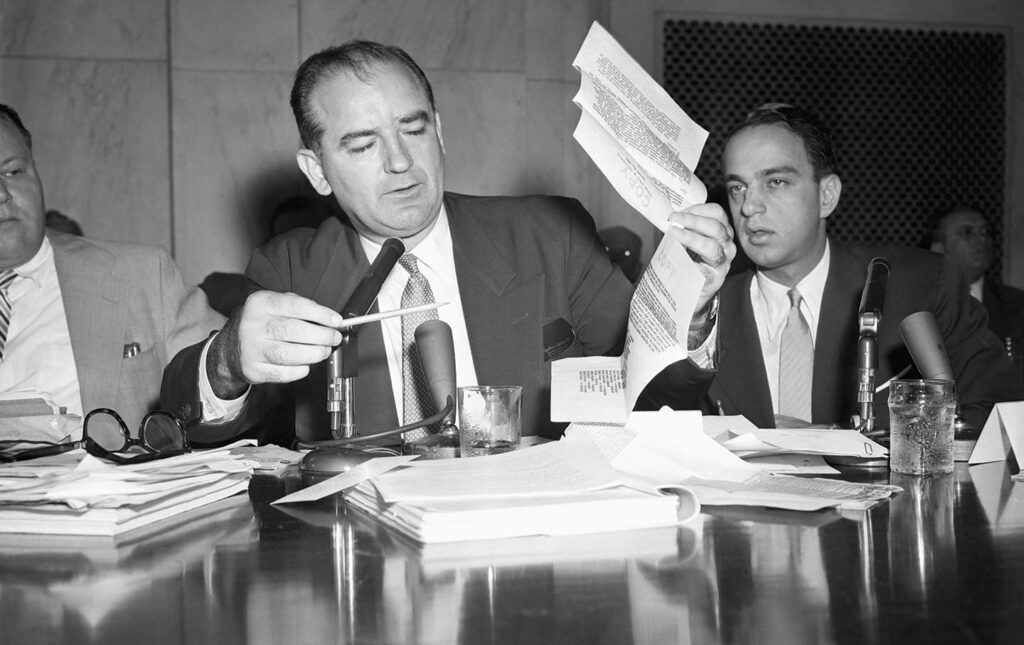

In both periods, anti-elite resentment was galvanized by politicians who had no respect for fundamental norms of fairness and decency, were willing to lie brazenly, and were deft at exploiting dissatisfaction and anxiety for personal and partisan gain. Joseph McCarthy, like Donald Trump, was an uncouth outsider to the Republican establishment who became so powerful that few in the party dared cross him. One difference: McCarthy was only a senator, so his power to shape American society was necessarily indirect. He could hold hearings and hurl accusations, but he had to rely on other parts of the government and society to deliver material punishments.

And where Truman required “loyalty” from federal employees, Trump has instituted a different sort of loyalty program altogether—firing anyone he deems insufficiently faithful to him (never mind the country) and appointing people to high office whose only qualification is their fealty to the boss. His administration resembles not so much a security state as an organized crime gang. And for that reason, among others, it is unlikely that Democrats will be co-opted by Trump the way many were by anti-communism.

Risen’s multi-textured account of how McCarthyism came to pervade every aspect of American life also reminds us that the current hysteria is, at least thus far, in no measure as deeply woven into the fabric of American life. The Red Scare lasted for more than a decade (and, if one includes the first Red Scare, even longer). It permeated every aspect of public and private life, and its investigations directly affected millions of Americans.

By contrast, apart from the “Big Beautiful Bill,” Trump’s initiatives thus far have largely been limited to unilateral executive orders and actions. Trump won reelection with less than a majority of the vote, and his poll numbers, historically low to begin with, are dropping. Red states are complicit, but blue-state attorneys general have challenged many of his initiatives in federal court, whereas Risen identifies only a handful of government officials who defied McCarthyism.

Moreover, thus far the courts have ruled against Trump on a wide range of his initiatives. A Bloomberg Law study counted more than 200 rulings against the administration. By contrast, the courts during the Red Scare did nothing to stop McCarthyism, and instead affirmed many dubious convictions and firings for mere political association. Only after the political tide had turned and the Senate censured McCarthy did the Supreme Court begin to dismantle the legal architecture of the Red Scare.

The legal turning point came on June 17, 1957, when the court issued four decisions against anti-communist measures. It overturned the contempt conviction of a union leader who refused to name names before HUAC. It reversed a New Hampshire decision that had held a Marxist professor in contempt for refusing to answer questions about his lectures. It reinstated a State Department employee who had been fired for disloyalty. And it vacated a conviction under the Smith Act, which criminalized Communist Party membership.

It was not until a decade later that the court went farther, ruling that one could not be punished for associating with the Communist Party unless one specifically intended to further its illegal ends, and could not be prosecuted even for advocating the violent overthrow of the US government unless one’s speech was intended and likely to incite imminent lawless action. These decisions remain good law to this day and are an important cornerstone of our First Amendment freedoms. But by the time the court issued these rulings, McCarthyism had become, as Dwight D. Eisenhower put it, “McCarthywasm,” and countless lives had already been ruined.

The most poignant parallels between the Red Scare and today involve the question of compliance or resistance. The Red Scare was very much a public-private partnership. McCarthy relied heavily on private institutions, including the entertainment industry and universities, to fire or blacklist those his committee contended were communists. A whole industry parasitic on anti-communism arose, first outing suspected communist sympathizers and then facilitating their “rehabilitation” through confessions, naming names, turning informant, and the like.

Many citizens were more than willing to go along. Out of 110 Hollywood figures called to testify before HUAC in 1951 alone, 58 cooperated, offering up 902 names. Much like some of the law firms that preemptively struck deals with Trump, some in Hollywood did not even wait to be called and instead reached out on their own initiative to name names. One such volunteer was the actor Sterling Hayden, who regretted it for the rest of his life. Even labor unions were complicit: The National Education Association expelled communist members in 1949, and the American Federation of Teachers voted not to defend teachers accused of communist associations.

The few who refused to go along suffered for their actions at the hands of both the federal government, which could prosecute them for contempt of Congress, and private industry, which refused to hire them. Dalton Trumbo, one of Hollywood’s most successful writers, refused to name names, served time in prison, and could find work only under pseudonyms. The noir author Dashiell Hammett served six months in prison for refusing to identify contributors to a bail fund. Gale Sondergaard, who won the first Oscar awarded for Best Supporting Actress, refused to name names and did not get another screen role for 20 years. Others were more fortunate. The playwright Arthur Miller declined to name names and was convicted of contempt, but his conviction was reversed on appeal. The Harvard physicist Wendell Furry refused to cooperate, but Harvard stood by him and, unlike others, he kept his job. Most of those who resisted suffered at the time; but in retrospect, they are the period’s heroes.

The same dynamic is in operation today, as some law firms and universities capitulate to Trump’s illegal demands, while others, such as the Perkins Coie law firm and Harvard University, courageously fight back. Here, too, history will likely look positively on those who stood on principle while condemning those, like Paul, Weiss and Columbia, that have chosen to comply with blatantly illegal orders.

In the first weeks of the second Trump administration, I appeared on a webinar with Ellen Schrecker, a historian of the Cold War. She began her remarks by saying that she had spent her career studying McCarthyism and the Cold War, and “this is worse.” I have my doubts. The Cold War, after all, lasted nearly half a century, spawned the modern surveillance state, and had the complete buy-in of federal, state, and local governments. Abroad, it led to millions of deaths in proxy wars; at home, it sent many people to prison for nothing more than exercising their right to association, subjected millions more to loyalty investigations, and led to the firing or blacklisting of countless innocent Americans.

Trump’s initiatives, as devastating as they have been, do not yet come close to matching the range and depth of the Red Scare. But then again, he’s only getting started.

_____________________________________________

David Cole is The Nation’s legal affairs correspondent and the George J. Mitchell Professor in Law and Public Policy at Georgetown University.

Go to Original – thenation.com

Tags: Communism, History, USA

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.