A Reassessment of Marx’s Theory as a Political Theory and a Theory of Conflict Resolution

PAPER OF THE WEEK, 12 Jan 2026

Prof. Antonino Drago – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract – I present an assessment of Marx’s theory based on a new understanding of the foundations of social science, consisting of two dichotomies. Based on these dichotomies, Marx’s theory implicitly assumed alternatives to those of the dominant economic theory of capitalism. However, his theory did not fully conform to these choices. Furthermore, I interpret Marx’s theory through Galtung’s recent theory of conflict resolution. At the time, Marx’s theory represented a major intellectual advance; its enormous relevance in the history of peoples over the last two centuries is also justified by this fact; however, it was ambiguous regarding the type of conflict resolution, whether violent or non-violent. Its ambiguities explain the historical regression of the Marxist movement and the societies subsequently constructed according to its theory. However, I demonstrate that both Marx’s theory and the Marxist movement paved the way, for better or worse, for a new, pluralist history of humanity.

- Two dichotomies as the foundation of the natural sciences

In Marx’s time (1848), almost all natural science belonged to the old paradigm (Newtonian), whose foundations were confused with metaphysics (recall, for example, the absolute space and absolute time of Newtonian mechanics). Instead, he wanted to construct an independent full scientific theory of both society and its historical dynamics. In fact, Marx founded his theory (primarily economics) without appealing to any metaphysical notions. In retrospect, we see that his theory is similar to the few non-metaphysical scientific theories of his time: chemistry, Sadi Carnot’s thermodynamics, Lobachevsky’s non-Euclidean geometry; unfortunately, they were largely ignored by Marx.

More than a century and a half later, scientific the theories alternative to the dominant ones are now numerous, so much so that by comparing them it is possible to accurately characterize the alternative nature of this type of theory and thus define the foundations of the natural sciences and, similarly, the foundations of the social sciences; (Drago 2016a) Through them, it is possible to characterize the model of an alternative theory and therefore accurately evaluate Marx’s theoretical effort for a new scientific theory.

In the past many scientific theories – for example Lazare Carnot’s mechanics (1783), classical chemistry (1789), Sadi Carnot’s thermodynamics (1824), Lobachevsky’s non-Euclidean geometry (1840), Einstein’s first quantum theory (1905), the theory of computation (1936) – have fundamental concepts and mathematical techniques which do not include the notion of actual infinity (AI) – for example infinitesimals, extreme points of a line, Newton’s fundamental notions – but only those that include the notion of no more than potential infinity (PI), the only kind of infinity that is actualized by operational means; for instance counting natural numbers in an unlimited way without reaching an ultimate number; approximating an exact value by an unlimited sequence of measurements, the results of which never achieve it (as scientists instead claim to achieve by appealing to AI and moreover maintain that this idealistic practice is the most productive for the progress of science). Furthermore, the organization of each of the above mentioned theories differs from the traditional, deductive one suggested by Aristotle (AO); the new organization is based on a crucial problem, and the theory seeks a new scientific method to solve it (PO).

In summary, the foundations of a scientific theory consist of two dichotomies, concerning the type of mathematics and the type of organization of a theory, respectively. Through these, the foundations of Newtonian mechanics are characterized by the following two choices: AI, because it uses infinitesimal calculus according to actual infinity, and AO, because the theory is derived deductively from the three famous principles-axioms (Drago 1988). In contrast, Carnot’s mechanics and the other theories mentioned above (with the exception of Einstein’s unnecessarily using one differential equation) do not use infinitesimal calculus, but only elementary mathematics, perfectly suited to operational physical notions; therefore, their choice of type of mathematics is PI. (Drago 2012) Moreover, each of these theories is a PO theory, since it is based on the search for a new resolution method of a given problem (respectively: which are the invariant magnitudes of an impact of bodies; which and how many are the elements of matter; which is the maximum efficiency of heat / work conversions; what are quanta of light; what is a computation). This second couple of choices, PI&PO, determines a model of scientific theory (MST) which is alternative to the MST of the AI&AO choices, inaugurated by Newton’s theory. It can be shown that the contrast between these two MTS gives reason of the history of classical Physics as well as the crisis of the early 1900s. (Drago 2013; Drago 2017a)

Three different representations of a MST are possible: first, the structural one which is constituted by the fundamental choices that determine the structure of a theory, i.e. the corresponding MST; second, the subjective one which is constituted by the notions that subjectively synthesize the fundamental aspects of this theory; third, the objective one which is constituted by the (mathematical and logical) tools which this theory makes use of. The following Table shows all them in detail.

Table 1. THE TWO MAIN MODELS OF A SCIENTIFIC THEORY (MST)

| Structural representation

(the one determined by the two fundamental choices) |

Subjective representation

(as scientists conceive it through surrogatory notions) |

Objective representation

(as teachers formalized it through tools of reasoning) |

|||

|

Newtonian MST (AO + AI) |

‘Dissolution of the finite cosmos and geometrization of space’ |

Classical logic

Analytic method Infinitesimal analysis (main example: differential equations of the 2° order) |

|||

| Carnotian MST

(PO + PI) |

‘Evanescence of the force – cause and discretization of matter’ |

Non-classical logic

Synthetic method Symmetry or cycle (main example: S. Carnot’s cycle in thermodynamics) |

|||

| Some centuries | One century | One generation | |||

Legenda: MST = Model of Scientific Theory; AO = Aristotelian Organization according to classical Logic; PO = Problematic Organization according to intuitionist Logic; AI = Actual infinity; PI = Potential infinity,

In the central column the several intuitive notions belonging to the subjective representation of a MST are summarized by a pair of propositions; the first pair was suggested by Koyré in order to summarize the subjective notions characterizing the birth of modern science (Koyré 1957); actually, they indicate the MST of Newton’s Mechanics, the theory to which the historical process of this birth was directed: ‘Dissolution [not PO] of the finite cosmos [not PI] and geometrization [AI] of space [AO]. (In square brackets the choices or refusals to which Koyré’s words allude; with his term ‘geometrization’ I mean the historical process of mathematization of reality that culminated in the calculus of infinitesimals applied by Newton’s theory to reality). For Carnotian physical theories I have suggested, in light of the alternative choices PI and PO, the pair of sentences: ‘Evanescence [not AO] of the force-cause [not AI] and discretization [PI] of matter [PO]’. (Drago 2017b, sec. 6.2-6.4) (The last line of the Table indicates how much time, on average, the elements of that representation persist before a change). (Drago 2016a)

As a fact, Newtonian MST has played a dominant role in the history of science, so much to devalue all theories of the alternative MST, i.e. the Carnotian ones, as “phenomenological”, “genetic”, “immature”; that is, as having each achieved only a first stage of development towards a future development which will necessarily lead them to be based on the choices AO and AI. Because of its dominant role, the first MST may be rightly called a “paradigm” in the sense of both Kuhn (Kuhn 1969, pp. 148ff.) and Feyerabend (Feyerabend 1975, 23ff.).

- An extension of the two dichotomies till to concern social sciences

A previous paper extended the two fundamental dichotomies, discovered in the natural sciences, to two fundamental dichotomies for the social sciences (Drago 2017b). The latter ones are represented by translations into social terms of the essential contents of the former dichotomies.

According to Alexander Koyré (1957), in the history of Western society the birth of modern natural science occurred when human mind made use of the notion of infinity within both mathematics and physics. In the same span of time, for the first time the notion of infinity has been actualized within social life by a process of infinite accumulation of money, i.e. the social process of capital’s growth (AI).[i] Moreover, it is clear that the idea of the organization of all the concepts and all the laws of a theory of natural science can be extended to the idea of the organization of the entire society; for example, the social organization determined by compulsive economic laws established by few capitalists, is analogous to the organization of a deductive scientific theory (AO), where every proposition is deductively derived from few axioms, located at the top of the theory.

We note that after a long period of time in which authoritarian social institutions (empires, kingdoms, centralized states) dominated society, in the time of French Revolution the above mentioned alternative scientific theories born; in particular, in opposition to the top-down organization of the aristocratic State (AO), two alternative movements born whose organizations were aimed at solving problems (PO) respectively, how people can gain civil rights (freedom) and (subsequently) how the movement of workers can obtain social justice; both their programs wanted to develop unlimited personal relationships (PI), through respectively new laws and economic constraints.

- A structural characterization of Marx’s theory

In history, the first social theorists conceived of society as a vertical organization governed by kings, armies, Church (AO) and its historical evolution as managed by, at the top of society, either nobles, or “geniuses”, or “an Absolute Spirit” (AI). These theories, being based on the AO&AI choices – that may include abstract and even mythical targets – supported idealistic interpretations of society.

The typical theory of capitalist economics, Adam Smith’s, may be characterized through the following two choices. He conceived the economic organization of society – generated by allowing full freedom of initiative to the cleverest persons – as governed by an “invisible hand”; which actually represents in metaphysical terms capitalists’ ability of organizing society according to AO. Moreover, the title of his most famous book was intended to suggest how the “Wealth of Nations” may be obtained; in reality, it presents the growth of capital (AI) within a country, in particular England, which at that time had rampant capitalists (and which, moreover, was accumulating a unlimited amount of resources from many colonized countries in the world). All in the above well represents in intellectual terms an authoritarian organization of capitalist society (AO), whose target is an unlimited increase of capital (AI).

Almost a century after Smith, Karl Marx started an important theoretical contribution to both economic science and historical consciousness of mankind. In order to rationalize his rejection of capitalist society in a convincingly way, the young Marx began a critical review of all social knowledge illustrating that type of society. He started with Hegel’s philosophy of right; but then he was attracted to Economics, whose study later absorbed almost all of his energy.

Marx interpreted the growth of capitalism as an infinite and absolute process (AI): “Accumulate, accumulate! This is Moses and the prophets!”[ii] His project was to eliminate the unlimited growth of capital in the development of humanity, by means of the human relations of all kinds, including the solidarity of the proletarian class also internationally, in order to ultimately achieve “a human society and a social humanity.” This means choosing IP.

Furthermore, his economic theory lacks any certain principle from which to derive, like theorems of the deductive method, economic or social laws (AO). Instead, he proposes to workers, exploited by capitalism, a revolution aimed at abolishing capitalist society (not OA). To this end, his major book presents—right from the title—a great universal problem (PO): how to understand the historical and social phenomenon of capital in order to invent a method for overcoming capitalism and then solving the problem of justice in society. His program for an alternative to the dominant organization introduced into people’s intellectual lives a social dichotomy that represents, in modern political terms, the ancient and universally recognized dichotomy: either freedom [for the most capable] or justice [for all].

In conclusion, Marx’s theory is characterized by the following two choices: the development of human relations to the level of class solidarity (PI) as a political alternative to the infinite growth of the social power of capitalism (AI); and the choice of an organization aimed at solving the problem of social justice (PO) by overcoming the domination of capitalism (AO), in order to ultimately build an alternative society[iii].

The above choices characterize Marx’s theory as an alternative theory, since they are directly opposed to both the social choices of dominant capitalism and the dominant theoretical choices of Smith’s theory (and, more generally, of “classical economics”). Furthermore, his choice pair is similar, within the natural sciences, to those of Carnotian MST (whose main theory is the mechanics of L. Carnot), which is an alternative to the choice pair of the dominant MST, initiated with the birth of Newtonian mechanics, which subsequently became the dominant theory.

Further evidence of the validity of this parallel between social and scientific theories is obtained by comparing Marx’s economic theory, based on the social choices PI and PO, with a theory of natural science, S. Carnot’s thermodynamics, based on the scientific choices PI and PO. Both theories deal with commodities that produce goods. But while the latter deals with any material commodity capable—through combustion in a heat engine—of producing a (social) good (i.e., labor), Marx’s theory deals with another commodity—namely, the labor power of workers— which in a factory produces , through manipulation of raw materials, goods. (Drago, Vitiello 1990) From this perspective, Marx extended the notion of “physical commodity” to the social notion (invented by him) of “labor power” and made it his fundamental objective category.

Further confirmation of this parallel is provided by the use of Koyré’s aforementioned categories to interpret the birth of modern science. They are given by a pair of sentences illustrated just after the previous Table. Let us now look for two pairs of similar sentences interpreting social phenomena in a way parallel to the previous pairs of sentences. Corresponding to Koyré’s pair that characterizes the dominant science, I suggest (Marx’s interpretation of) the birth of capitalism: “Dissolution [not PO] of the commodity economy [not IP] and capitalist monetization [AI] of the entire market, including workers [AO].” Similarly, Marx’s theory of the alternative society can be characterized by the pair of sentences: “Extinction [not AO] of capitalism [not AI] and a society based on justice [PO] through the growing solidarity of the working class [IP].”[iv] (Drago 2017b)

In summary, the aforementioned concordance between Marx’s theory and Carnot’s theories concerns all three representations of a scientific theory: in their structural representations, both share the same choices (IP and OP); in their objective representations, Marx’s theory extends the objective notion of commodity; and similar sentences à la Koyré characterize their subjective representations[v]. This characterization of Marx’s theory demonstrates that his aim of formulating it as a theory of the natural sciences was successful. Today we see that it shares the main elements of all three representations of a scientific theory; but, correctly, only the elements of the alternative theories (chemistry, thermodynamics, etc.), those of the Carnotian MST.

This assessment of Marx’s theory is more appropriate than the common philosophical characterization, according to which this theory is the result of a “superseding” of Hegel’s philosophy; in reality, this suggested philosophical process has not yet been made clear.

We also note that the above assessment qualifies Marx as the first economist to base his theory not on some notions related to the natural or social sciences (space, market, trade, prices, taxes, etc.) or, at most, directly linking (as Smith does) his basic notions to the two choices, AI and AO, which he considered the only possible ones. Rather, he grounded his theory by characterizing all four fundamental choices a scientific theory can make: both the choices of the dominant theory and those of the alternative theory. In other words, Marx also introduced into economics the intellectual conflict between opposing choices and theories; and this conflict is radical in nature, because it concerns two alternative scientific foundations.

It could be argued that precisely because his theory of society was radically alternative (even in the “scientific” sense) to the dominant one, Marx was able to suggest a political program for radical social change. Furthermore, precisely because he based his theory on the structure of two dichotomies—the two dominant choices and the two alternative choices—Marx revealed for the first time the structural aspects of science, which include a fundamental conflict between the alternative choices on the dichotomies; a conflict that provides implicit support for his revelation of conflicts within society (master-slave alienation, economic surplus, class division of society, class struggle, economic exploitation of workers by the capitalist, historical laws of capitalism’s defeat, etc.). In the past, this theoretical contribution of Marx occurred in the absence of any other theory of conflict resolution. This further characterization of Marx’s theory is on par with the other two characterizations—political and economic.

Therefore, Marx’s theory not only concerns politics and economics (which he also unites), but also includes a theory of social conflict resolution; albeit ignored as a theory. (We will discuss this after the next section, which more accurately characterizes the previous political-economic interpretation of Marx’s theory.) Thus, his program, founded on such profound foundations, generated a radical political movement around the world.

- A More Detailed Examination of Marx’s Political-Economic Theory

However, Marx’s theory partially corresponds to the above characterization.

A first reason for this ambiguity is that his entire work remained unfinished; during his lifetime, The Capital was only partially published. At his death, his initial, gigantic program of studies remained unfinished, even in economic matters. It is obvious that subsequent interpretations of what his theoretical thought essentially represented were controversial.

The second reason is that Marx’s critique of the social and historical development of capitalism does not concern the productive forces, which he sees—like capitalism itself—as a positive development throughout human history. Although he aimed to halt the growth of capitalism through an anti-capitalist political revolution of the workers, Marx’s theory believed in the inevitable progress of the productive forces. According to Marx, the historical progress of humanity (in technological and scientific factors and in human knowledge) was inevitable and essentially positive because would ultimately lead to the fall of capitalism; therefore, by developing these social forces, the bourgeoisie “digs its own grave.” For this reason, Marx harshly criticized Ludd, the mythical worker who attempted to thwart the technological progress introduced in his factory with new machines.

But today we well-know that the historical development of productive forces is ambiguous; if it is “tamed” by humanity, it contributes to the development of its self-sufficiency, social interrelations, and human knowledge; all represent IP development. But if it occurs independently of the political will of the people, as absolute growth (similar to the development of the Hegelian Absolute Spirit), it subordinates human life to the absolute power of a new fetishism, technology; in this case, it represents the choice of AI. Marx gave way to an almost fatalistic interpretation of history: due to the inevitable development of the productive forces, the proletariat would simply replace the bourgeoisie in the management of society, which would be carried forward by the same productive forces as before. He never resolved this ambiguity in his political theory.

The third reason is that his friend, Friedrich Engels (an industrial entrepreneur), wrote a controversial book, Anti-Dühring, advocating the idea that economic progress alone (AI) is the lever for political progress towards the new society of the proletariat. In the preface of the book Engels states that he wrote some of its parts together with Marx (whose economic survival he financed); this statement involved Marx in supporting this reductive conception of the liberation of the proletariat.

The fourth reason is that Engels erroneously presented Marx’s thought as belonging to an exclusive philosophical tradition, the German one; and worse still, to its idealist tradition, whose basic choices were clearly opposite to those (implicitly) chosen by Marx, PI and PO. Truly, Engels presented Marx as a reversal of this idealistic tradition; but there followed no common agreement on what kind of reversal Marx’s theory represented.

Thus, the Engelsian version of Marx’s theory overshadowed Marx’s choice for IP: his IP choice got confusing with the opposite AI choice of both absolutized technological progress and idealized German philosophy. Also his choice for PO was confused with the choice for AO: while awaiting Marx’s clarifications on his overturning of Hegel’s dialectical philosophy, Engels acted in politics in an authoritarian manner (OA) (see his authoritarian leadership of the Second International).

The ambiguities listed above – here accurately characterized thanks to the fundamental choices – explain the great difficulties encountered by scholars of the past in interpreting Marx’s theory. Although very different interpretations have been suggested over the last century, none of them have been widely accepted.

- Marx’s theory of social conflict and his theory of conflict resolution

Thanks to its implicit awareness of alternative choices, Marx’s theory was the first in the history of social theories to openly introduce the notion of conflict[vi]. Let us then examine Marx’s theory as a theory of social conflict.

A previous article (Drago 2016b) presented a general theory of conflict resolution (CR). It applies the basic idea of Galtung’s definition of conflict: an A-B-C. This acronym means the following points:

1) A conflict includes three independent dimensions, all coexisting within it.

2) They are: A, assumptions, preconceptions; B, behavior, objective facts; C, contradiction, subjective experience of conflict[vii]. These three dimensions are a consequence of Galtung’s non-violent attitude, which takes into account not only, as usual, the facts (B) and feelings (C) regarding the two parties in conflict, but also their basic motivations (A) in the face of conflict; in fact, it is by taking into account above all the motivations that the non-violent method can be able to suggest how to achieve a cooperative attitude between the two opposite parties.

He who follows a violent method can easily offer a rational justification for a violent final solution to the conflict, up to the suppression of the adversary; it is enough for him to describe the conflict according to only one of the three previous dimensions, seen as an absolute jsutification; the adversary can be judged guilty – and therefore to be repressed – because either he has committed substantially evil actions (B), or constitutes a public threat to everyone’s life (C), or has totally negative motivations (A). This is why those who are moved by a violent attitude close their mind within a narrow – because one-dimensional – vision of the conflict. Conversely, he who perceives only one dimension of the conflict rarely manage to reach a consensual resolution, even if he has a peaceful attitude leading him to appeal to values (A), or to carry out good deeds and offer kind words (B); or, even less, to appeal to the best feelings (C).

In the history of humanity, the birth of the Courts represented advancement in humanity’s effort to find a more adequate conflict resolution; firstly they take into account the dimension of the facts (B); moreover they are considered in the light of the other dimension of the laws that can be assumed as commonly accepted rules (A) to resolve all conflicts. However, a non-violent conflict resolution process is even more advanced because it looks for an agreement that does not leave aside or repress any dimension of the two parties. In other words, inspired by nonviolence (A), one has to invent an intelligent strategy capable to reconcile justice (B) with mutual charity (C) which is instead ignored by a Court.

It should also be noted that the bourgeois class has produced its own theory of the history of humanity; but regarding conflicts this theory was elementary. Above all, it recognized the historical dynamic of an unlimited and mythical growth of Capital upon itself. Within this kind of history the bourgeoisie obviously considered wars committed by its state because the latter one legitimizes its social power. However, he ignored conflicts within the social life; it ignored to be the cause of class conflict. Rather it viewed workers as refractory to its growth through some negative behaviors (B): indolence at work and protests aimed at obtaining higher wages. The bourgeoisie opposed these social reactions essentially through its social power within a liberal society, i.e. to push the political powers to apply the state laws, guaranteeing the prerequisites for the growth of capitalism (A): freedom of private property and freedom of enterprise. Therefore, for its defense, the bourgeoisie appealed to an already accomplished intellectuality, that is, to liberal jurisprudence. Instead, the proletariat had to rationalize its conflicts by starting from scratch; as a fact, it has laboriously created new ideologies that motivate its opposition to the political power of bourgeoisie; they were based on the claim of social justice (dimension A of the proletariat), to be achieved also by overcoming liberal laws (dimension A of the bourgeoisie). Therefore, the different ideologies (A) of these two social groups presented antagonistic contents so much so as to be a priori mutually incompatible.

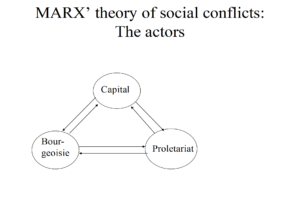

In the history of conflict theory, Marx’s theory represents a qualitative leap in humanity’s understanding of social conflict. Marx characterized it in structural terms, that is, he recognized its origin in the structure of society, divided into different classes. Furthermore, he saw this struggle as conducted not by two, but by three social actors: beyond the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the laws of Capital, which dominate society and govern the history of humanity. More precisely, these laws cause the problems of dimension A of class conflict; the bourgeoisie applies these laws to social life, in particular to working-class life; this application constitutes dimension B; the social contradictions suffered by the proletariat due to the management of social life by the bourgeoisie exploitation within the factory and oppression within society represent dimension C. To them the proletariat tries to react through social actions that Marx ideology directed towards a revolution.

Figure 1:

The conflictual dynamics of society is generated by all the interactions of these three social actors: social contradictions (C) lead workers to react (B) to the politics of the bourgeoisie applying the laws of capital (A).

The conflictual dynamics of society is generated by all the interactions of these three social actors: social contradictions (C) lead workers to react (B) to the politics of the bourgeoisie applying the laws of capital (A).

Marx illustrated the structural dynamics of class conflict through three writings, which correspond exactly to the A, B, C dimensions of this conflict. The Parisian manuscripts represent the proletariat’s experience of social contradictions; that is, the subjective experience (C) of structural oppression, caused by the domination of Capital (A); this writing ignores the social organization (for example bureaucracy, the army, technology, industrial development, etc.) managed by the bourgeoisie, because here Marx, following a subjective point of view, feels that all institutions are distant (including trade unions, elsewhere defined as a “gilded cage” that imprisons the proletariat). Instead, in Das Kapital Marx tries to describe the objective historical dynamics of a society, as results from the application (B) of the economic laws of Capital (A) by the bourgeoisie managing the proletariat (which here passively suffers these laws). Finally, Fragment on the machines is an attempt to analyze (ignoring the proletariat) how the economic laws of Capital (A) will change in the future due to technological advances; this document represents the conflict between the bourgeoisie, which manages society (B), and the future development of capital (A).

We conclude that, as a whole, Marx’s theoretical framework on social conflict, being well suited to the harsh social and ideological conflict existing in the society of his time, was far superior to bourgeois social ideology, which almost ignored the two representations, structural and subjective, of that conflict and furthermore misinterpreted its dynamics.

- The limits of the Marxian theory of conflict resolution

In Marx’s time the conflict resolution usually resorted to violent methods, up to the suppression of the opponent. But the birth of the factory conflict introduced an exception, since a capitalist could not suppress his opponent, the proletariat, otherwise the production of goods and therefore his profits would have ended. On the other hand, even the workers could not succeed in repressing the boss, because the factory would have been closed, leaving them without work and without wages. The factory was therefore the first social space in which (collective) conflicts had to be resolved without suppressing the opponent, although one of them, the proletariat, was evidently the weakest, a born loser.

Workers learned to fight capitalists mainly through strikes. In material terms, the strike constitutes a method of struggle of a non-violent nature: first of all, it does not repress any actor. Furthermore, it entails a greater cost for the workers themselves (who do not receive wages) compared to the capitalist, who must bear a limited reduction in industrial production and therefore in his earnings. Furthermore, in social terms, the strike is a breakdown in the solidarity of common citizenship; a workers’ strike calls on civil society to put pressure on capitalists to ensure better working relations and better wages.

Furthermore, the limitation of violence in factory life led the society to introduce laws allowing unions; who then empirically discovered new techniques and new methods of struggle, all of a non-violent nature; above all, dialogue and negotiation. Therefore, the practice of conflict resolution within a factory introduced non-violent methods of collective conflict resolution, which then were exported into social life[viii].

Let us now consider Marx’s theory of social conflict resolution more closely.

For Marx the overall result of resolving the class conflict was clear; this conflict had to be resolved through historical progress, attributing political power to the proletariat who will manage a new historical era of humanity. But this positive resolution of class conflict had a prerequisite: the exploited class had to acquire social power through internal growth, that is, by becoming aware of the historical development of society as a whole. Therefore, Marx’s slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” invited the proletariat not to carry out an immediate revolt and/or to build an army as armed as possible, but rather to grow in awareness of the possibility of a historical revolution, which, spreading from one country to another, would change the history of humanity. The acquiring historical consciousness, being a nonviolent historical process, did not necessarily have to result into violent social actions[ix]; in fact, Marx, Engels and even Lenin contemplated the possibility of a democratic resolution of class conflict, where the word “democratic” means historical change without social trauma, e.g. through political elections. (Schaff 1973)

Furthermore, once again one has to remind that Marx’s theory remained unfinished. In particular, Marx did not detail the social processes through which the consciousness of the proletariat could grow, nor the historical change of the proletarian class, from “a class in itself” to “a class for itself”, that is, a proletarian class capable of pursuing the universal interests of all humanity as its true interests. Nor did he have enough time to describe in detail the historical change that had to lead to the seizure of political power. Furthermore, Marx’s theory on class conflicts in everyday life was different from the best, because he did not notice the historical novelty of the exclusion of direct violence within factories.

Therefore, Marx illustrated his immediate awareness of the dynamics of social conflict without taking into account a third party (which also means mediations); being dualistic it was inevitably antagonistic. Thus, his main legacy was his emphasis on the subjective harshness of conflict within a factory; it was intended as a lesson to be learned for the social class conflict which had to add forcefully reactions to the bourgeoisie applying the economic laws of capitalism to social life.

Wanting to change the world after philosophers had interpreted it, Marx recognized the Hegelian philosophy of historical and social processes as the most advanced interpretation of this change, as subject to dialectical laws. Whose, however, he recognized the bourgeois origin: this dialectical logic determines its final result with a mere verbal addition of a negation to the verbal description of a negative social situation; in otehhr terms a not operative, idealist operation revealing the theological nature of Hegel’s thought. As a fact, Marx conceived class conflict in such radical ideological terms that he contrasted two types of logic; on the one hand the reasoning of the bourgeoisie according to classical logic and on the other the reasoning of the proletariat according to a new type of dialectical logic. Marx wanted to correct Hegel’s dialectical laws by turning up-down its theological attitude, so that Hegel’s dialectical logic should be transformed into a dialectical logic that expresses a proletarian type of arguing. However, Hegel’s logic was never formally defined (today we know that it is only a confused philosophical anticipation of modern intuitionist logic). Furthermore, it has never been decisively changed in proletarian terms. In short, Marx even claimed an alternative logic, but was unable to qualify it satisfactorily. In conclusion, Marx was only partially aware of the best way to resolve a social conflict.

It thus left ample space to theorize a pragmatic management of an increasingly bitter class conflict, which finally led to conceiving the desired historical change that would allow the rise of the proletariat to social power as the (physical?) suppression of the enemy (the capitalists) also through an upheaval of society such as a war.

- The history of the Marxist movement

Even more ambiguous than Marx’s theory was the history of the Marxist movement, which later became the most important workers’ movement. This movement was much larger and more powerful than previous political movements promoted by appealing to scientific theories; for example. the one scattered throughout the world of former students of the École Polytechnique, who spread technological progress in all countries to mobilize social life everywhere; or that of chemists, who spread Lavoisier’s new chemistry as a new intellectual world (Ben-David 1975).

All of the above suggests that Marxism must be conceive according to the alternative scientific theories. Unfortunately in the past almost all Marxist theorists linked it to philosophy, as a combination of Hegel’s philosophy (whose dialectics however should have been “reversed”) and materialist philosophy; and, to take real society into account, they concentrated their attention on a science that seemed to be a certain science of society also because it had been the main subject of Marx’s studies, that is, contemporary economics.

Already during Marx’s lifetime, Engels (through the book Anti-Duehring) reduced the entire theory to a merely economic representation of capitalism; it was the so-called “vulgar Marxism”, which ignored the role played by civil society in relation to class conflict. Thanks to Engels’ leadership, it determined the politics of the Marxist movement. The other theorists, without suspecting that Marx’s point of view could be characterized by the two alternative choices, also valid for characterizing the foundations of other scientific theories, improved Marx’s theory very little.

Furthermore, Marx’s conflict resolution theory was reductively simplified to represent class conflict as a conflict between only two actors, namely capitalism and the proletariat, the bourgeoisie being conceived as mere executors of the former’s rule.

In this way “the dialectical movement of the historical conquest of social power by the proletariat” became a historical law of transcendent nature, so much to miss a clear political strategy; and the conflict resolution theory was reduced to the simplest possible one: the usual, vulgar dualistic representation of a violent conflict, the resolution of which was simply the suppression of the other. This theory was maintained in these sharp terms also to distinguish it from the wing of reformist social democrats, willing to compromise with the formal democracy of the bourgeoisie. The overall result of these shortcomings was the conception of the historical revolution as an act of violent elimination of the other party; that was the opposite practice of non-violent conflict resolution by both workers and unions within a factory. Therefore the two policies of the two main institutions of the proletariat – trade union and party – did not agree. This ambiguity generated a tension between the daily politics of the workers inside the factory, on the one hand, and the general politics of the party outside the factory, on the other.

Moreover, subsequent Marxist theorists were not capable of radical innovations that improved the theory, despite the fact that in the meantime a new historical phase of capitalism had begun (companies managed by boards of directors, the birth of multinationals, a decrease in the role of the State in society), plus within democratic societies the introduction of universal suffrage,

The First International of the Marxist movement included anarchists. Marxists agreed with them not only on the overcoming of capitalist society (not AI), but also on a self-sufficient organization of society (PO). Yet Marx wanted to increase the central power of the movement leadership (AO), thus clashing with the anarchist Bakunin (1871), who abandoned the movement. During the Second International, Engels adopted an even more authoritarian attitude, which, for example, expelled Dühring from the International, because the latter’s influence on the workers could surpass that of Marx. Furthermore, Engels planned (against Marx’s opinion; see Marx’ Critique of the Gotha Program, 1875) an alliance with the radical wing of the bourgeois class. In 1896 almost all anarchists left the Movement.

Then Lenin theorized that, since the proletarians were not capable of independently achieving awareness of historical processes, the leadership of the movement had to be composed of professional intellectuals; who had to give themselves an authoritarian role, so much so that the union had to function as a transmission belt for the commands of the Party they directed. Therefore, since the times of the First International and even more so since the times of the Second, the workers’ movement has undergone an authoritarian direction (AO).

Even worse happened among the Russian Marxist revolutionaries. Lenin imposed his leadership and a vertical organization (AO), first on the group of Bolsheviks (Scherrer 1979), and finally on the Soviets (originally the workers’ parliaments) who had previously conquered the leadership of the large movement that made the Russian revolution. After winning the revolution, Lenin imperiously organized the Party-State (for example, in 1922 he assimilated to it the popular movement Proletkult (Workers’ Culture), created in 1917 to promote an alternative to bourgeois culture in order to make the proletarian class a class in itself). Shortly after Lenin’s death, Stalin imposed an overt dictatorship (AO) on the Russian people, which went far beyond the political justification of having to force the people to make a social transition towards the last socialist society of the proletarian class: it was one of the harshest in the history of humanity. Furthermore, through the Third International, the USSR imposed a top-down organization on all the Marxist parties in the world (AO).

Even more unfortunate was the fate of the PI choice. Duehring, a socialist mathematician, was very active in introducing an alternative to the dominant scientific theories, particularly in both Mathematics and Mechanics. By writing the book Anti-Dühring on purpose, Engels forced the International to expel him. Subsequently, Engels established a clear distinction between natural sciences (in which the object of study is objective for all social classes, therefore also for the proletarian class) and social sciences (in which human and social actions can change the preconditions of the object of study; therefore only in this case is the proletarian class the historical bearer of an alternative science)[x]. Consequently, Engels’ book (and his program for the International Conference of Gotha (1875)[xi]) led the Marxist movement to abandon any search for the discovery of an alternative within the natural sciences and hindered any idea of technological development alternative to the bourgeois one. This attitude excluded any attempt to question the growth of machines (as occurred through the introduction of Taylorism in the factories) in relation to the work of workers. Subsequently, the historical task of the proletarian class was no longer conceived as a change in the productive forces, but only as a change in the social institutions of the bourgeoisie (primarily the State). Its task was therefore reduced to replacing the bourgeoisie in only the management of the same productive forces as before (including science and art; for one of the last programs for an alternative science see: Bogdanov 1918, Anonymous 1960).

Surprisingly, the Marxist revolution did not first take place in England or Germany, the most advanced countries in historical progress, but in backward Russia; this implied that his people were the least prepared to face the enormous problems of the post-revolution. When Lenin planned the economic development of the USSR, he launched the slogan “Electrification [AI] plus Soviet [PO]”; he mistakenly thought that political relations among workers were sufficient to limit and control technical and scientific imperatives. The result was that the entire Marxist movement no longer recognized an alternative to capitalist technological development which subsequently progressed independently of political constraints; see for example the introduction of Taylorist slavery in Russian factories, which was exalted in its aberrant socialist version, Stakhanovism, and later was exalted as the best development of the productive forces, which now grew independently of politics. Especially at the time of the Third International, the choice of incessant technological development led the USSR to finally fall into a fundamental political contradiction: that of building nuclear weapons that would instantly destroy millions of proletarians in the enemy country; so that the defense of one’s nation subordinates the class solidarity of the workers of the world.

Constrained by military technological imperatives, the Marxist movement ultimately understood the historical process of overcoming the bourgeoisie through a catastrophic military confrontation, although the Army’s fundamental choices (arms race: AI; and organization of lines and personnel: AO) are opposite to the choices of the original Marx’s theory. Ultimately this Movement reaffirmed both Western military progress and the dominant theory of a violent conflict rersolution; they were the same as the choices of the dominant society[xii].

Forty years after the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Cultural Revolution sought to renew the search for political control over technology; but he had the same naive attitude as Lenin: reading Mao’s “red book” should have taught workers how to use technological tools (for example the lathe). Ultimately, even socialist China built nuclear weapons for its own national “defense”; later this country transformed the choice for social development based on justice (PO) into the choice to become a leading economic power in the world, even more than capitalist countries (AO).

Consequently, already a few decades after Marx’s death, the original alternative choices of his theory (PI & PO) appeared to have almost vanished. It is not surprising that in this story the leaders of the proletarian class have taken on an ambiguous role, not very different from that played by the leaders of a capitalist society[xiii].

Marxism promised a historical transition from capitalism to a PI society, whose human relations were to dominate the productive forces. But the USSR definitively postponed the creation of the new society to a very distant future. As a matter of fact, no “true socialist” society in the world has achieved its planned goal.

Because of this confusion of fundamental choices caused by an authoritarian policy that leaves freedom to capitalist technological progress, the Marxist movement has not introduced a new type of conflict resolution[xiv].

Marxist theory, having degenerated into a program for violent revolution, pursued disruptive class conflict in each country, ultimately resulting in civil war. Having won in several countries (both by political and military means), this political project has polarized all the states of the world by aligning them into two opposing blocs, ready for mutual suppression. For forty years this conflict has threatened a global military confrontation that could lead to global destruction. It was the most terrible conflict in the entire history of humanity. This world policy demonstrated that each Bloc was blind to any conflict resolution alternative to the military (nuclear) one.

According to the evaluation of Marx’s theory, some events of the 1980s appear to be a wise recovery of the political program of the workers’ movement. First, the worldwide demonstrations against Euromissiles relieved a large Western popular base that wanted a non-military conflict resolution. Then Gorbachev decided to unilaterally stop the nuclear arms race (non AI), an act that introduced non-military means of conflict resolution (as the first dialogue of trust) between the two Blocs. Finally, in 1989, popular movements arose in the socialist countries of Eastern Europe; their aim was to solve the problem of their freedom from deceitful dictatorships, which claimed to represent “workers’ dictatorship”. These movements involved a large number of citizens to recover the two alternative fundamental choices, a self-management organization (PO) and the development of human relations (solidarity) (PI) to carry out highly risky and unprecedented actions according to a new theory of conflict resolution, i.e. non-violence[xv]. By leveraging these choices they managed to successfully react in a non-violent way to the brute force of repression. They therefore demonstrated that a new type of collective conflict resolution, in addition to the military one, is possible in Europe.

- The Marxist movement in the context of past revolutions of the last century

Marx’ theory teaches that to overcome capitalism the workers’ movement must draw fundamental lessons from historical facts. Today the Marxist movement is disconcerted by historical facts that contradict the main predictions of Marxist theory. They are the historical events that occurred in the years around 1989: the fall of the USSR and many socialist countries. Does this fall represent the end of Marxism as well as its historical goal of liberating humanity from capitalism? Even academic studies, after four “generations” of scholars on the topic of social revolutions, do not know how to evaluate this subject of study (Drago 2010, chapter 2). In the absence of a theoretical framework in which to evaluate the historical meanings of the 1989 revolutions, the previous two distressing questions remain without a certain answer.

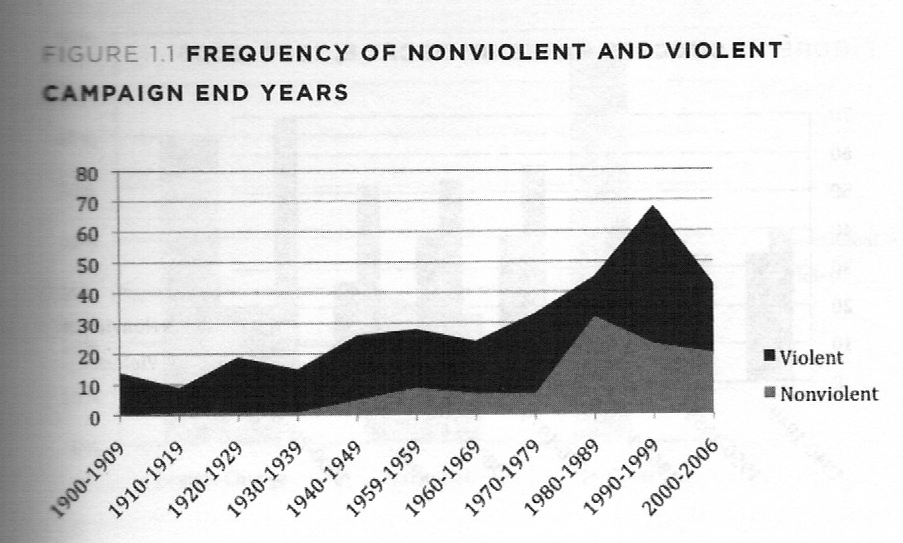

However, a decisive step forward has recently been made. Two Californian researchers have created a database of all the revolutions that occurred in the last century (1900-2006) (the authors neutrally call them “Campaigns”). Their statistical analysis of the main aspects of these revolutions produced surprising results (Drago 2010, chapter 1, based on data anticipated from an article by the two authors of the subsequent book; Chenoweth and Stephen 2011).

First of all, the number of these revolutions is very large: 323; have been repeated several times in most of the world’s 198 countries (apart from Western democratic countries). Secondly, among these revolutions, the number of non-violent ones was very considerable (about a hundred or a third). Even more surprising is that the number of these types of revolutions increases over time, as the following figure shows.

Fig. 2: The revolutions of the last century (from Chenoweth and Stephen 2011, p. 84):

Fourth, the political importance of nonviolent revolutions is great: 53% of them won, while only 24% of violent revolutions were successful. In particular, in Latin America the percentage of victories of non-violent revolutions was 83% and in the former Soviet Union 80%. Last but not least, after a nonviolent revolution the resulting government is more stable than after a violent revolution.

In light of this assessment of a century full of revolutions, we can conclude that Marx’s ambiguities, deviant interpretations of his theory, and the Marxist movement’s deviations from the original motivations of the proletariat have led to tragic consequences. Violent revolutions and wars have been doggedly pursued by those who ironically believed they had a truly scientific awareness of the history of humanity; and who therefore also opposed the ability of peoples to carry out revolutions non-violently (which instead were one out two successful). The birth of a new type of conflict resolution also had to overcome the strong opposition of the Marxist movement which claimed, on scientific grounds, to be the only one to liberate all the peoples of the world.

In retrospect, we can conclude that the birth of the Marxist movement was characterized by the birth of a radical alternative to the dominant society; but subsequently that movement gradually abandoned this alternative, due to the ambiguities of both its political theory and its theory of conflict resolution, ultimately military catastrophic, but considered as an inevitable result of technological progress. Its dictatorial political leadership ignored any alternative to violent revolution, even though it threatened imminent global destruction, and maintained its warped ideology to the end. Finally the peoples inside the Socialist Bloc have demonstrated a wise ability to make revolutions according to a new theory of conflict resolution, the non-violent one.

- The current perspective of the pluralism of development models

To draw a deeper historical lesson than that of the many revolutions of the last century, we must broaden our attention to the entire history of Western civilization and select there those few revolutions that represent the most decisive ones for the history of humanity. We can certainly say that these revolutions are the ones that have changed the entire development model (MoDv), that is, at least one of the two fundamental choices of society: either the choice of the type of organization or that of the type of development. We therefore note that the MoDv based on the pair of choices AI&AO was born more than two centuries ago with the English (1688), American (1783) and French (1789) revolutions; the MoDv PI&OA was born with Lenin’s revolution in Russia (1917). The MoDv AI&PO was born with the Iranian revolution of 1979 and then with the Arab Spring of 2011. The MoDv PI&PO was perceived as an actor in world politics fifty years after the Indian revolution led by Gandhi; that is, after non-violence had spread throughout the world to such an extent that in 1989 the non-violent revolutions of the peoples of Eastern Europe took place; not only did they avert the immediate threat of sudden destruction of all the peoples targeted by a nuclear exchange between these two blocs, but they also erased the aberrations of the dominant blocs, since, on the one hand, they overthrew the “proletarian” dictatorships of the second MoDV and, at the same time, abolished, in international politics, the global division of peoples established at Yalta in 1945[xvi].

In the last century, the Russian Revolution caused a shock to humanity, representing the first mass departure from the consolidated Western MoDV. This revolution occurred in a backward country because, rather than representing a direct and unique alternative to the liberal MoDV, it merely acted as a centrifugal drive from it. After this revolution, its leaders chose the policy of developing the socialist MoDV only within Russia (“Socialism in one country”). Thus, not only were the communist parties of other countries were oppressed by the development of a foreign country, but also other MoDVs had to emerge independently and in opposition to the building of socialist MoDV in Russia. Finally, in 1989, the Gandhian MoDv’s revolutions led humanity away from the antagonism of just two established MoDvs (embodied by two Blocs encompassing all countries), to enter into a coexistence of diverse MoDvs, as proposed by the pluralism of four MoDvs. The birth of this pluralism was a shocking event in Western culture, which for centuries had been based on a “winner-loser” conflict resolution model, without possible agreements for coexistence between enemies[xvii]. Therefore, current political thought is disconcerted because it must abandon a long theoretical tradition (at least the tradition of the Hobbesian motto “Homo homini lupus“) that once seemed irreplaceable, to enter into a pluralism that had never been theorized before[xviii]. The Arab Spring affirmed that Arab countries also wanted to be included in this pluralist world.

Today, the novelty of this pluralism of four MoDvs is not entirely evident because, while the first three MoDvs have representative states—more or less powerful—the fourth MoDv does not yet have a representative state (not even India), but only grassroots movements (for example, the Porto Alegre meetings) or simultaneous demonstrations around the world (the first in February 2003 against the US war in Iraq; currently, Greta’s movement for the survival of the Earth). Therefore, the stronger states do not receive political pressure from the fourth MoDv because it is not represented by states (and if these states existed, they would still be neglected by the stronger states, which still base international relations on their economic arrogance and nuclear deterrence, that is, on two attitudes that do not belong to the fourth MoDv)[xix].

The other two MoDvs (Socialist and Arab) have representative states. But the socialist MoDv, after the defeat of 1989, is blindly experimenting with a new type of politics, and the yellow MoDv must emerge from a backward civilization that the Western MoDv can still hope to absorb through colonialist methods, particularly the (capitalist) market economy and Western jurisprudence[xx].

But today we can embrace this pluralism precisely because it corresponds to the scientific one, based on the four MSTs. These MSTs offer the appropriate scientific basis for every social group wishing to establish and develop its own MoDv, even without a sudden revolution. In particular, only today could a social revolution be planned that fully understood how to build a MoDv, because only today did we know that it had to be coherently shaped on the basis of two fundamental choices, based on their specific language and strategy, and based on the scientific attitude characteristic of the MST, which has the corresponding pair of choices.

In retrospect, according to previous assessments of the history of Marxism, six factors were fatal to it:

- In the past, the development of science and the philosophy of science was inadequate to understand the foundations of the natural and social sciences and thus to provide a truly scientific basis for planning a social revolution.

- Marx’s attempt to construct a new science of economics for his time was incomplete and insufficient.

- The leadership of the Marxist movement had an even poorer understanding of scientific culture and

- The leadership of the Marxist movement had an even lesser understanding of scientific culture and historical consciousness.

- Furthermore, it unfortunately never paid attention to the theory of the conflict resolution, although workers and unions had already begun to renew it. By choosing violence, that is, the backward (capitalist) attitude in the conflict resolution, it actually acted against its own policy of introducing people to a truly new society. Most leaders of the Second International adopted a violent approach to resolving class conflict; thus, both the practice of harsh dictatorships over the peoples conquered by socialism and the technological arms race prevailed over the continuous improvement of political theory.

- The success of the first Marxist revolution in a backward country placed the revolutionary movement in a very difficult situation, because both the movement and its leadership ignored the fact that it represented anything more than the initiation of a local alternative to escape the first MoDv. It ignored the final stage in the historical evolution of Western civilization—not the victory of a particular group in Western society over others, to the point of their repression, and even globally, but the coexistence of more political attitudes. In other words, it ignored the historical introduction of a new history of the pluralism of the four MoDvs; in particular the birth of a MoDv practicing a non-violent conflict resolution.

- It is not surprising that the USSR accepted the slavery of Taylorism and catastrophic military wars; and it also failed to establish (through the philosophy of “dialectical materialism,” Diamat) an alternative to social science and even an alternative to natural science (recall the fiasco of the Lysenko experiment).

Consequently, the greatest and most generous attempt in human history, sparked by the Marxist movement, to transform capitalist Western society into a global civilization of “human sociality and social humanity” failed. In light of the pluralism of the four MoDvs, we see in retrospect that the Marxist movement has the great historical merit of having initiated the first exit from the first MoDv materialized by Western society, and then, after the victory of the Russian Revolution, the merit of having sparked a seventy-year-long attempt to find an alternative to the construction of a new MoDv. That is, during this period, it had the task of breaking the monopoly of the Western MoDv and also of anticipating, for better or worse, a pluralism that still awaits full development today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous (1960), “Il proletariato e l’arte”, “La scienza e la classe operaia”, in Rassegna Sovietica, pp. 184-9.

Ben-David J. (1985), The Scientist’s role in Society. A comparative Study, New York: Prentice-Hall.

Beyer W. (2002), “The Flaw in the Peoples’ Army”, Peace News, Jun-Jul. https://peacenews.info/node/3985/flaw-peoples-army.

Bogdanov A. (1911), Kul’turnye zadachi nashego vremeni (Cultural problems of our times), Moscow.

Bogdanov A. (1918), Science and the Working Class, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bogdanov_(1918)_Science_and_the_Working_class.pdf.

Bukharin N. et al. (1971), Science at Crossroad, London: Frank Cass.

Chenoweth E. and Stephen M.J. (2011), Why Civil Resistance Won. The strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, New York: Columbia U.P..

Clausewitz K. (1832), On War, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/clausewitz-on-war-vol-1

Drago A. (1988), “A Characterization of Newtonian Paradigm”, in Scheurer P.B., Debrock O. (eds.): Newton’s Scientific ami Philosophical Legacy, Dordrecht: Kluwer Acad. P., pp. 239-252.

Drago A. (2007), “The birth of Non-violence as a Political theory”, Gandhi Marg, 29, no. 3 oct.-nov., 275-295

Drago A. (2010), Le rivoluzioni non-violente nell’ultimo secolo. I fatti e le interpretazioni, Roma: Quale Cultura.

Drago A. (2012), “Pluralism in Logic. The Square of opposition, Leibniz’s principle and Markov’s principle”, in Béziau J.-Y. e Jacquette D. (eds.), Around and Beyond the Square of Opposition, Basel: Birckhaueser, pp. 175-189.

Drago A. (2013), “The emergence of two options from Einstein’s first paper on Quanta, in Pisano R., Capecchi D., Lukesova A. (eds.), Physics, Astronomy and Engineering. Critical Problems in the History of Science and Society, Scientia Socialis P., Siauliai, pp. 227-234.

Drago A. (2016a), “New Interpretative Categories for Natural and Social Sciences”, Advances in Historical Studies, 5, pp. 223-239, http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs:

Drago A. (2016b), “Improving Galtung’s A-B-C to a scientific theory of all kinds of conflicts”, Ars Brevis. Anuari de la Càtedra Ramon Llull Blanquerna, 21, pp. 56-91.

Drago A. (2017a), Dalla storia della Fisica alla scoperta dei fondamenti della Scienza, Aracne, Roma.

Drago A. (2017b), “Koyré’s revolutionary role in the Historiography of Science”, in Pisano R., Agassi J., Drozdova D. (eds.), Hypotheses and Perspectives in the History and Philosophy of Science. Homage to Alexandre Koyré 1892-1964, Berlin: Springer, pp. 123-141.

Drago A., Vitiello O. (1990), “The cycle method vs. the analytical method in thermodynamics”, in A. Diez, J. Echeverria, A. Ibai (eds.), Structures in Mathematical Theories, San Sebastian, pp. 349-356.

Feyerabend P.K. (1975), Against Method. Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge, London: New Left Books.

Habermas J. (1989), The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jaurès J. (1911), L’armée Nouvelle, Paris: L’Humanité.

Koyré A. (1957), From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe, Baltimore MD: U. Maryland P.

Kuhn T.S. (1969), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago: Chicago U.P..

Marx K. (1867), Das Kapital, Hamburg: O. Meissner.

Marx K. (1983), Mathematical Manuscripts, New York: New Park. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Mathematical_Manuscripts_1881.pdf

Schaff A. (1973) “Marxist Theory on Revolution and Violence”, J. of History of Ideas, 34, 2, 263-279.

Scherrer J. (1979), Bogdanov e Lenin: il bolscevismo al bivio, in Storia del Marxismo, Torino: Einaudi, vol. 2, pp. 493-546.

Sohn-Rethel A. (1975), “Science as an alienated consciousness”, Rad. Sci. J., no. 2-3, pp. 65-101.

Weber M. (1992), The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, London: Routledge.

Wikipedia: “Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Domela_Nieuwenhuis

NOTES:

[i] Unfortunately, most scholars of the foundations of economics have ignored this category, as if the unlimited growth of capital were an elusive premise of their macroeconomic analyses or a distant result of their microeconomic an alyses.

[ii] Marx 1867, vol. 1, end of chapter 22. Note that the characterization of the subjective representation of capitalism (i.e., capitalist life) was left to a bourgeois scholar, Max Weber (Weber 1991). This characterization, too, relies on the choice AI. Weber recognized devotion to the infinite growth of capital as an essential characteristic of capitalist life; this devotion requires the capitalist to adopt an ascetic attitude, which in effect prolongs the medieval religious attitude of infinite personal growth toward God.

[iii] Further evidence of these choices is found in Marx’s mathematical works. In his later years (1880–84), he intensively studied various theories on the foundations of infinitesimals in an attempt to re-establish these intriguing notions. (Marx 1983) He rejected the metaphysics of infinitesimals (which he called “the ghosts of dead quantities”) (AI) and the dominant axiomatic attitude (not AO); indeed, he finalized his theory to solve the problem of what infinitesimals are (PO); and he chose an operational point of view close to that of Constructive Mathematics (PI), born a few decades after his death.

[iv] These statements also align with the categories of one of the most important Marxist historians of pre-capitalist economics (Sohn-Rethel 1975).

[v] Another, much more detailed, formal connection has been provided by (Saslow 1999).

[vi] Note that Western thought is highly resistant to including it. Even Thomas Kuhn’s famous history of science, whose title includes the word “revolutions” (Kuhn 1969), does not represent real conflicts. It describes a continuous historical evolution of science (“normal science”) and then argues that “scientific revolutions” exist, each of which abruptly replaces the old paradigm with a new one through a shift that occurs instantaneously in the minds of all scientists, like an inexplicable Gestalt phenomenon. However, Kuhn did not study the revolution in early 20th-century physics, but only a lateral event, the shift from Priestly’s chemistry to that of Lavoisier.

[vii] Sigmund Freud is known to have depicted an internal conflict through the three internal actors that together constitute a personality: the superego, the ego, and the id; clearly correspond to A, B, and C, respectively. Even the military man Klaus von Clausewitz (1838, section 1.1.28) declared that his strategic thinking on war was characterized by “a fascinating trinity”: “What is war?… As a total phenomenon, its dominant tendencies always make war a fascinating trinity, composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which must be regarded as a blind natural force; by the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and by its element of subordination, as an instrument of politics, which makes it subject to reason alone”; that is, respectively, B, C, and A. Note that the essential novelty of Clausewitz’s thought was the inclusion of politics (A) in strategic thinking.

[viii] Recall that the other 19th-century CR theory, that of Freud, proposed the cooperative resolution of internal conflict. It is built on the foundation of human relationships; The nonviolent method of dialogue generates a resolution process (through a “transfer”).

[ix] Note that the famous slogan “Power is in the barrel of a gun” was attributed by Marx to the bourgeoisie, not the proletariat. None of the previous leaders practiced civil disobedience, and, of course, no one was aware of Gandhi’s new methods and techniques for resolving mass conflicts, developed first in South Africa, starting in 1909, and then in India, especially with the famous Salt March of 1931.

[x] The error of this conception is to assume natural science as a single theory, without variants or alternatives, as if it had no questionable principles and did not use questionable mathematical techniques—so questionable as to allow for different formulations of the same scientific theory (for example, in mechanics: Newton, L. Carnot, Lagrange, Hamilton, Hertz, etc.). The differences between these formulations clearly depend on different philosophies of science and, ultimately, social ideologies. In other words, the mistake was to assume the Newtonian paradigm as a neutral axiom with such an exclusivist attitude that it monopolized the notion of “science.” Lenin repeated the same mistake even when the emergence of special relativity and quantum mechanics overcame that paradigm. In the 1930s, the failures of the USSR’s initial economic plans prompted Stalin to offer compensation to the expectations of foreign communist parties; he claimed that an alternative natural science had been launched in the USSR, according to the idea of a “proletarian science” (Bukharin et al. 1971); but Stalin soon thereafter repressed this. This was again vindicated through a state-led experiment in agriculture (led by Lysenko), which, however, proved a resounding failure. Finally, in the 1950s, Stalin liberalized scientific research, accepting the mainstream science. Against this reunification of bourgeois science with the USSR, the student movement launched a slogan that opposed both capitalist science and the scientific involution of the USSR: “Science is not neutral!”

[xi] In this light, Marx’s manuscript, “Critique of the Gotha Program,” represents his last-ditch attempt to reverse the dominant trend in the Second International. Subsequently, this trend was countered by Bogdanov’s book on the Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1911) and later, in the 1960s, by the Chinese Cultural Revolution. But all three attempts were unsuccessful.

[xii] In fact, Trotsky was tasked with building a new type of army for the defense of post-revolutionary Russia; but Trotsky’s repression of both the Kronstadt anarchist rebellion and Makhno’s attempt at an autonomous policy led the revolutionaries to confirm the Western type of army as the most effective.

[xiii] In reality, Marx and Engels (and almost all subsequent Marxist theorists) were not workers, but bourgeois.

[xiv] The Dutch pastor Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (Beyer, 2002; Wikipedia) wanted to introduce a peaceful and non-violent attitude into the Second International. But in the early twentieth century, he abandoned the Movement because he believed the Second International was inattentive to the issue of peace. Within the socialist movement, the most important attempt to innovate the conflict resolution was Jaurès’ theory of a new national defense; he understood this primarily as a popular defense based on coordinated strikes by the two peoples which were countered by the bourgeoisie through war (Jaurès 1911). It is no coincidence that he was assassinated the day before the outbreak of the First World War.

[xv] It is no coincidence that the most important of these revolutions was the Polish Revolution, in which the main social actor was a trade union, Solidarity, and its pivotal event was the workers’ nonviolent defense of an important site of nonviolent bargaining for the union, namely the Gdańsk shipyard factory. In fact, the new method for resolving social conflicts within factories was extended by Solidarity to the entire social life.

[xvi] For a presentation of a general theory of nonviolent politics, see (Drago 2007).

[xvii] Evidence of this shock, even 30 years after the event, is the senseless historical assessment: “The Fall of the Berlin Wall,” which nullifies peoples as political actors, their non-violent method, and their denial of the single strategy planned by all states: nuclear annihilation.

[xviii] Recently, Jurgen Habermas (Habermas 1998) has attempted to propose cultural and political pluralism.

[xix] Within a country, “realist” politicians view any Green MDS movement as merely pre-political, useful when channeled into their realpolitik programs, and, ultimately, useful for drawing innovative ideas and extracting budding leaders from it. Here lies the complete opposition between the “two politics”: on the one hand, the innovative politics of grassroots movements, and on the other, the conservative politics of states and all their institutions (decision-making and power), especially the dominant political institution, all sharing the politics of Jacobin-style parties (aiming to win 50%+1 of the vote to impose their program on everyone).

[xx] In reaction to this rapprochement between the states of these MoDvs, extremist groups (in the socialist MoDv, the South American guerrillas and in the yellow MoDv, ISIS) want to conquer alternative states through armed struggle.

______________________________________

Prof. Antonino Drago: University “Federico II” of Naples, Italy and a member of the TRANSCEND Network. Allied of Ark Community, he teaches at the TRANSCEND Peace University-TPU. Master degree in physics (University of Pisa 1961), a follower of the Community of the Ark of Gandhi’s Italian disciple, Lanza del Vasto, a conscientious objector, a participant in the Italian campaigns for conscientious objection (1964-1972) and the campaign for refusing to pay taxes to finance military expenditure (1983-2000). Owing to his long experience in these activities and his writings on these subjects, he was asked by the University of Pisa to teach Nonviolent Popular Defense in the curriculum of “Science for Peace” (from 2001 to 2012) and also Peacebuilding and Peacekeeping (2009-2013. Then by the University of Florence to teach History and Techniques of Nonviolence in the curriculum of “Operations of Peace” (2004-2010). Drago was the first president of the Italian Ministerial Committee for Promoting Unarmed and Nonviolent Civil Defense (2004-2005). drago@unina.it.

Prof. Antonino Drago: University “Federico II” of Naples, Italy and a member of the TRANSCEND Network. Allied of Ark Community, he teaches at the TRANSCEND Peace University-TPU. Master degree in physics (University of Pisa 1961), a follower of the Community of the Ark of Gandhi’s Italian disciple, Lanza del Vasto, a conscientious objector, a participant in the Italian campaigns for conscientious objection (1964-1972) and the campaign for refusing to pay taxes to finance military expenditure (1983-2000). Owing to his long experience in these activities and his writings on these subjects, he was asked by the University of Pisa to teach Nonviolent Popular Defense in the curriculum of “Science for Peace” (from 2001 to 2012) and also Peacebuilding and Peacekeeping (2009-2013. Then by the University of Florence to teach History and Techniques of Nonviolence in the curriculum of “Operations of Peace” (2004-2010). Drago was the first president of the Italian Ministerial Committee for Promoting Unarmed and Nonviolent Civil Defense (2004-2005). drago@unina.it.

PAPER OF THE WEEK STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Capitalism, Conflict Resolution, Economics, Karl Marx, Marxism, Politica Theory

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 12 Jan 2026.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: A Reassessment of Marx’s Theory as a Political Theory and a Theory of Conflict Resolution, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.