The Real Nuclear Danger Isn’t Iran or North Korea

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, 10 Aug 2015

Analysis: The most dangerous nuclear nations are the U.S. and Russia, the ones with nearly all of the weapons.

“Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.” — President John F. Kennedy

Seventy years after the first atomic explosion lit up the New Mexican desert and nearly 25 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, both Russia and the United States retain nuclear postures from the darkest days of their rivalry. There are almost 16,000 nuclear weapons still in the world today, and the U.S. and Russia possess 94 percent of them. Worse, 1,800 of these Russian and American weapons sit atop missiles on hair-trigger alert, ready to launch on a few minutes notice.

Few people are even aware of these dangers. Most have forgotten about the weapons. They think the only nuclear threat is the chance that Iran might get a bomb. Or that plans are in place that effectively prevent or contain nuclear threats. They are wrong. On any given day, we could wake up to a crisis that threatens our country, our region, our very planet.

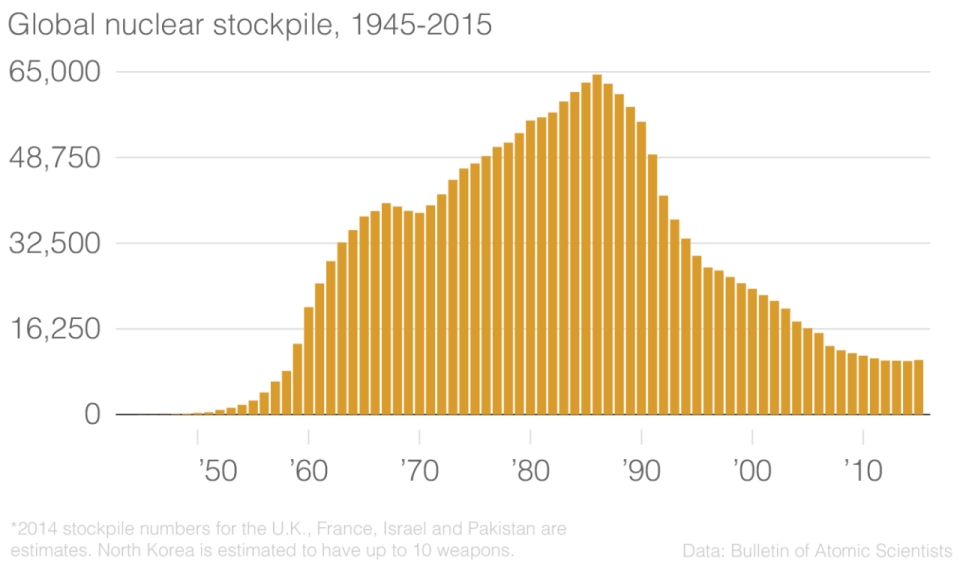

There is good news. The size of these arsenals has decreased dramatically in the last 30 years. When Ronald Reagan and Leonid Brezhnev squared off in the 1980s, pouring new nuclear missiles into Europe, there were more than 70,000 nuclear weapons in the world. Mass protests and the wisdom of Reagan and his negotiating partner Mikhail Gorbachev, who succeeded Brezhnev as the head of the Soviet Union, led to arms control treaties that slashed arsenals by 50 percent.

The restraint of the two nuclear superpowers rippled to other nuclear aspirants. More countries gave up nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons programs in the past 30 years than tried to get them. And these were tough cases, including Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, the nuclear successor states to the Soviet Union: Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan, and Iraq and Libya.

In turn, the American and Russian arsenals were cut 50 percent further under Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. President Barack Obama, early in his term, trimmed them a bit more. And the entire interlocking network of global treaties and security arrangements has gone a long way to providing tougher inspections, more rigorous export controls on nuclear technologies, better security over “loose nukes” and nuclear materials, and more formidable barriers to new states getting weapons.

Indeed, while people talk of “states like Iran and North Korea,” there actually are no states like Iran and North Korea. Apart from the eight countries with established programs there are no other governments racing to get the capability to build nuclear weapons.

And here, there is more good news. The nuclear agreement with Iran is a major step in stopping the spread of nuclear weapons. If we can contain North Korea’s program, or strike a similar deal, it then becomes possible to talk about the end of the wave of proliferation that began 70 years ago. Global intelligence officials are clear: There is no other nation looming on the new-nuclear-state horizon.

Even as proliferation risks decrease, however, the risks of accident, miscalculation or intentional use of one of the existing nuclear weapons is unacceptably high. Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, we have come closer to Armageddon than many realize.

In January 1995, a global nuclear war almost started by mistake. Russian military officials mistook a Norwegian weather rocket for a U.S. submarine-launched ballistic missile. Boris Yeltsin’s senior military officials told him that Russia was under attack and that he had to launch hundreds of nuclear-tipped missiles at America. He became the first Russian president to ever have the “nuclear suitcase” opened in front of him. But Yeltsin trusted U.S. officials, and he was confident that there was no hidden crisis that might prompt a surprise attack by the U.S. With just a few minutes to decide, Yelstin concluded that his radars were in error. The suitcase was closed.

American nuclear weapons, too, have often come within a hair’s breadth of detonation.

In 1958, a B-47 crew accidentally dropped an H-bomb that exploded near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Luckily, only the weapon’s conventional explosives detonated, but the crater can still be seen.

In 1961, a B-52 carrying two armed weapons broke apart over Goldsboro, North Carolina. Two bombs dropped from the bomb bay. One bomb’s parachute deployed and carried it safely to the ground. The other fell all the way down. All of the weapon’s safety mechanisms failed, save one. A single low-voltage switch, the technical equivalent of a light switch, prevented a hydrogen bomb from destroying a good portion of North Carolina.

As the numbers and deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons declined, accidents also decreased, but they did not end. In 2007, a B-52 flew from Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, carrying 12 cruise missiles on its wings. Unbeknownst to the crew, six of the cruise missiles were armed with nuclear warheads.

The missiles traveled across the nation and spent the night sitting on the tarmac guarded by just a few security officers and a barbed wire fence before their true nature was discovered. The really bad news? No one at Minot ever noticed that they had gone missing.

One has to be a true optimist to believe that we can leave 16,000 nuclear bombs in fallible human hands indefinitely and nothing will go wrong.

It could get worse. The world’s nuclear weapons are aging. Bombs, like cars, wear out and eventually have to be replaced. We are now in a generational transition, when the weapons built during the terrifying Cold War rivalry of the 1980’s are ready for retirement. This could be a good time for Russia, the United States and other nations to close down these obsolete arsenals and save billions of dollars.

Instead, the nuclear nations are raiding their treasuries to build an entire new generation of the deadliest weapons ever invented. As Hans Kristensen and Robert Norris point out, “nuclear nations have undertaken ambitious nuclear weapon modernization programs that threaten to prolong the nuclear era indefinitely. … New or improved nuclear weapon programs underway worldwide include at least 27 ballistic missiles, nine cruise missiles, eight naval vessels, five bombers, eight warheads, and eight weapons factories.”

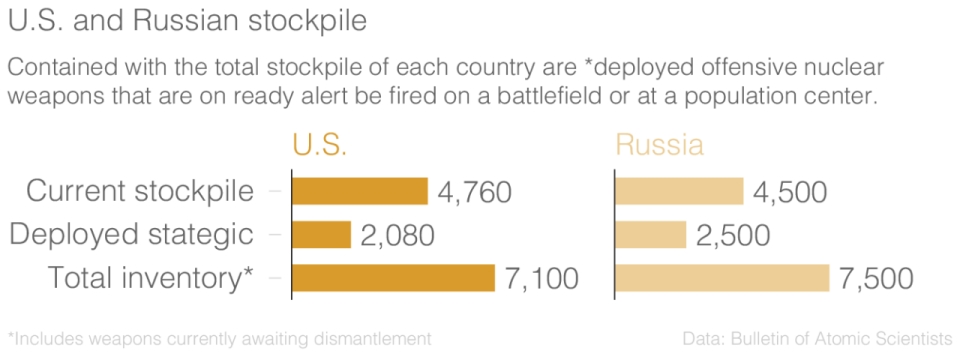

The world doesn’t need more nuclear weapons. Russia currently has the largest nuclear arsenal, with a total of approximately 7,500 warheads. The United States is second, with roughly 7,100 warheads. Other nuclear weapons states have far fewer. France possesses 300, China 260, and Great Britain, 225. Pakistan has about 120 weapons and India 110. Although Israel has never acknowledged its nuclear weapons stockpile, it is estimated to have nearly 80 weapons. North Korea has enough material for less than 10 bombs but has not deployed any.

Current global nuclear arsenal

| Country | Warheads |

| Russia | 7500 |

| U.S. | 7100 |

| France | 300 |

| China | 260 |

| Great Britain | 225 |

| Pakistan | 120 |

| India | 110 |

| Israel | 80 |

| North Korea | <10 |

Sources: US Nuclear forces, 2015, Russian nuclear forces, 2015, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Note: Not counted above: The U.S. has 2,340 warheads awaiting dismantlement; Russia has 3,200. Some numbers above are estimates, for example, it is estimated North Korea has the material for up to 10 bombs, but has not deployed any.

Nuclear weapons are not cheap. According to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, U.S. nuclear weapons spending alone is estimated to reach $348 billion over the next decade, while arms control experts estimate that it could reach up to $1 trillion over the next 30 years. Russia is also increasing the role of nuclear weapons in its strategy. But why?

It is difficult to think of a military combat mission that requires the use of even one nuclear bomb. There has not been one in 70 years. Perhaps there is a mission that might someday require one bomb. Or ten. Or an arsenal of 500. But the United States has 7,000. This is beyond all logic and military need. Clinging to these obsolete weapons is a vestige of Cold War thinking propped up by contracts and the desire of those with nuclear bases to keep the few thousand jobs they provide. Pandering to these parochial motives and flawed strategies risks catastrophes whose financial and human costs dwarf any conceivable benefits.

Pope Francis told a conference on nuclear threats in Vienna this year that “spending on nuclear weapons squanders the wealth of nations.” He questioned the morality of maintaining these huge arsenals for any purpose. These horrific weapons, he said, must be “banned once and for all.”

Seventy years after it was born on the sands of Alamogordo, there is a growing global sense that it is time to retire the Bomb.

Go to Original – aljazeera.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: