Solidarity Economics: An Idea Whose Time Has Come

EDITORIAL, 26 Nov 2018

#562 | Prof. Howard Richards – TRANSCEND Media Service

As is generally true in the cases of intractable social problems–drugs, militarism, global warming, etc.–also in the case of low wages and precarious employment, in order to solve the problem, it is necessary to redefine the problem. Especially when we are dealing with socially created realities–as we are when we try to solve the problems of low wages and precarious employment–we should bear in mind that the ways people think about the problems create them. If people are going to solve the problems, they need to think differently.

Solidarity economics redefines the problems. The problem is not how to attract more investors to create more jobs at higher pay. The problem is how to liberate humanity from physical dependence on the confidence of investors to meet their vital needs. Solidarity economics is an epistemological break and a political strategy. It is an epistemological break because it deconstructs the 18th century European foundations of economic and social thought. It is a political strategy because it slowly but surely builds a plural economy capable of resisting the chantage of capital flight and disinvestment.

Buckminster Fuller suggested a question I find helpful for redefining a problem like low wages, and hence for solving it: How can we make the world work for 100% of humanity without ecological damage?[i] Remembering Ludwig Wittgenstein who said that the purpose of his philosophy was to show the fly the way out of the fly bottle, I suggest that If we focus on Fuller’s question, and not on conventional questions like How can we attract more investment? The fly is already on its way out of the fly bottle.

Many pioneers already realize that the reliable and sustainable creation of dignified livelihoods requires an epistemological break. They have already concluded that a living wage for everybody who needs one is not going to come to pass through any possible permutation of conventional economic thinking framed by conventional liberal philosophy and jurisprudence. The time is long past when we can expect every human living on this planet to make a good living by selling something –labour power or something else—to buyers willing and able to buy it at a price high enough to comply with human rights and meet human needs. Moving resources from where they are not needed to where they are needed–capturing rents and transferring surpluses—has got to come. The Roman Law iron cage of European “civilization” has got to go. European-rooted global law must demote itself to the status of servant, not master, of Europe’s Judeo-Christian heart. Europe must demote itself to the status of a peninsula of Asia whose savants are no wiser than Gandhi, Confucius, Julius Nyerere, Nelson Mandela or Paulo Freire.

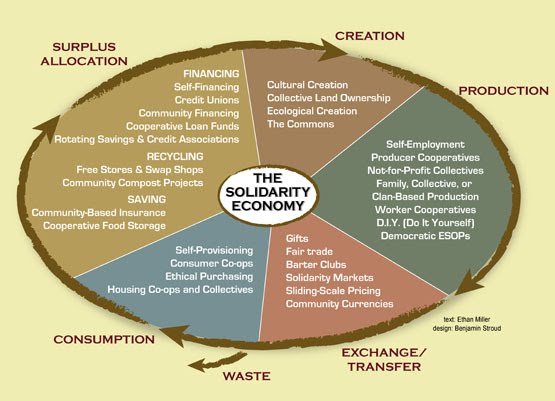

Many pioneers are developing alternative economies. A good umbrella name is “solidarity economy” although many other names are used, and although there are places in the world where people cringe at the very mention of “solidarity” because it has been the smokescreen for unworkable crackpot ideas, corruption, empty supermarket shelves, and terror.

Pioneers are already building a solidarity economy, also known as a caring economy. In the UK, the New Economics Foundation, inspired by E.F. Schumacher, is one of a number of limey think-tanks with its feet on the ground, doing as well as thinking. Its proposals for making workers co-owners of the firms where they are employed are as I write (September 2018) being incorporated into the platform and programme of the Labour Party. Emily Kawano who helped start and for nine years directed a Center for Popular Economics at U. Mass Amherst, recently published a list of seven practical things we can do to build the solidarity economy, the first of which is to increase self-provisioning and community production.

In Buenos Aires where there is a graduate programme in social economics at the Universidad Nacional General Sarmiento, its director, José Luis Coraggio is among those organizing on-the-ground worker-owned enterprises and cooperatives as a form of economic resistance to neo-liberal austerity. Jean-Louis Laville is among those similarly combining theory and practice in France. On a website supported by Catholic Charities (Caritas) of Spain almost every week there is a new example of building the new society in the shell of the old.

This week it features a community currency popularly called “El Zoquito” recently launched in the city of Jerez de la Frontera. In the Executive MBA programme at the Graduate School of Business of the University of Cape Town, students and teachers study “authentic leadership” putting people and planet first, and that means working to rebuild the system from within the system as Saint Francis worked to rebuild the church from within the church. The list goes on. Solidarity economics is not only a growing body of economic theory ignored by the mainstream academic establishment. It is also a growing social movement ignored by the mainstream media establishment.

The proliferation of such communitarian and socialistic practical initiatives around the world gives me hope that their sum will solve a decisive problem. The decisive problem in question, in the words of Mikhail Kalecki, is that capital has a veto power over public policy. It has a veto power because if investors lose confidence, there will be an economic crisis. Because of that veto power, to restate the gist of Habermas’s concept of legitimation crisis, society is ungovernable. Deciding what is rational, or what is right, is too often a fruitless exercise, because what is rational and/or right is regularly overruled –-if I may state the same point a third way (referring not to Kalecki or Habermas but this time to Robert Boyer, Michel Aglietta and David Harvey)—by the imperatives of a regime of accumulation. As the world is now organized, keeping capital accumulation going, come hell or high water, has become the necessary condition for meeting the physical needs of the people.

Solidarity economics is not about building a more successful regime of accumulation (like a developmental state), but about “graduating” (to use Bucky Fuller’s term) to a world where life no longer physically depends on obeying the systemic imperatives (to use Ellen Wood’s phrase) of any regime of accumulation.

Solidarity economics is needed to supplement the efforts of the moderate left to save the world from the presently dominant amalgam of neoliberal theory and sheer corruption. The moderate left concentrates on correcting market failure. That is not an inspiring idea. Solidarity is. Fighting corruption requires a stronger dose of ethics than the moderate left prescribes. But perhaps the greatest illusion that moderate left economists have to overcome in order to see the need for a different and more inspiring ethic is the illusion that it is possible for Scandinavian social democracy to make a comeback and to become once again a model for the rest of the world. It is time to frankly admit that while capitalism does not work and Communism does not work, social democracy does not work either.

Solidarity economics is building alternative economic power on the ground. It is making neighbourhoods more self-sufficient, communities more resilient, individuals less alone. To repeat Mikhail Kalecki’s point, capital really does have veto power over public policy, because any policy it does not like–for good reasons, bad reasons or no reasons–will cause an economic crisis. Whatever the specious reasons may be that the neoliberals give and the left tries to refute, for adopting policies that favour the rich, it remains true that with or without reasons, those of us who have more than we need hold economic power. Like it or not, meeting the physical needs of everybody depends on producing goods and services, while producing goods and services depends (not entirely but too much) on the decisions of the investing classes. Paul Krugman gives an instructive example: In Brazil in 1999 there was no unusual or dangerous federal government deficit. There was no inflation to speak of. There was an economic slowdown, in the face of which moderate left economists on the side of the angels like Krugman and Yanis Varoufakis would counsel expansion, not austerity. Nevertheless, the investment community decided that Brazil was a bad risk because of the government’s deficit spending. Krugman continues: “But what was the use of arguing? Investors believed that Brazil would have a disastrous crisis unless the deficit was quickly reduced, and they were surely right, because they themselves would generate that crisis.”

Now, if a decisive issue is who is able to get production going so that the babies will be fed, and who can paralyze the economy for good reasons or bad reasons or no reasons, then the five examples of solidarity economy I mentioned above –worker participation in the ownership of firms, self-provisioning, community production, community currencies, and authentic leadership —are steps in the right direction.

Understanding why the achievements of the social democrats when the moderate left led governments proved to be unsustainable, should lead to seeing solidarity economics as a logical response, as a regrouping and rethinking in the light of the downfall of social democracy and the rise of neoliberalism. It should lead to seeing the shadow side of the ideals of the 18th century that founded economics as a science as well as modern jurisprudence and political philosophy. The Asian origins of Buddhist and Gandhian economics, and the South American origins of solidarity economics narrowly defined, and (with respect to South America) its roots in two kinds of tradition that predate the 18th century ideals –namely the social doctrines of the Roman Catholic church and the buen vivir of indigenous pre-Colombian cultures—should be clues that solidarity offers modernity a heart it lacks.

_____________________________________________

Prof. Howard Richards is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He was born in Pasadena, California but since 1966 has lived in Chile when not teaching in other places. Professor of Peace and Global Studies Emeritus, Earlham College, a school in Richmond Indiana affiliated with the Society of Friends (Quakers) known for its peace and social justice commitments. Stanford Law School, MA and PhD in Philosophy from UC Santa Barbara, Advanced Certificate in Education-Oxford, PhD in Educational Planning from University of Toronto. Books: Dilemmas of Social Democracies with Joanna Swanger, Gandhi and the Future of Economics with Joanna Swanger, The Nurturing of Time Future, Understanding the Global Economy (available as e-books), The Evaluation of Cultural Action (not an e book). Hacia otras Economias with Raul Gonzalez, free download available at www.repensar.cl. Solidaridad, Participacion, Transparencia: conversaciones sobre el socialismo en Rosario, Argentina. Available free on the blogspot lahoradelaetica.

Prof. Howard Richards is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He was born in Pasadena, California but since 1966 has lived in Chile when not teaching in other places. Professor of Peace and Global Studies Emeritus, Earlham College, a school in Richmond Indiana affiliated with the Society of Friends (Quakers) known for its peace and social justice commitments. Stanford Law School, MA and PhD in Philosophy from UC Santa Barbara, Advanced Certificate in Education-Oxford, PhD in Educational Planning from University of Toronto. Books: Dilemmas of Social Democracies with Joanna Swanger, Gandhi and the Future of Economics with Joanna Swanger, The Nurturing of Time Future, Understanding the Global Economy (available as e-books), The Evaluation of Cultural Action (not an e book). Hacia otras Economias with Raul Gonzalez, free download available at www.repensar.cl. Solidaridad, Participacion, Transparencia: conversaciones sobre el socialismo en Rosario, Argentina. Available free on the blogspot lahoradelaetica.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 26 Nov 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Solidarity Economics: An Idea Whose Time Has Come, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

[…] Solidarity Economics: An Idea Whose Time Has Come […]