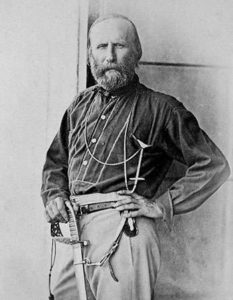

Giuseppe Garibaldi (4 Jul 1807 – 2 Jun 1882): Godfather of Transnational Democratic Politics

BIOGRAPHIES, 29 Jun 2020

René Wadlow – TRANSCEND Media Service

Giuseppe Garibaldi, born in Nice, now France, often called the hero of two worlds because of his efforts for independence in Latin America and then Europe, is in many ways inventor of transnational democratic politics. He was brought up in a religious Catholic family; his mother hoped that he would become a priest. However, the Church of Pope Leo XII had fallen asleep in its dreams of past glories. Garibaldi saw the need for change, and for a mystic motor to produce that change. Thus at 26, he joined the Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini. Young Italy was the public face of the Carbonari with its overlapping membership with that of Freemasonry, both outlawed throughout Italy, except in the Piedmont.

The factor uniting the Carbonari and Freemasonry was a militant opposition to the Roman Catholic domination of Italy . Both the Carbonari and Freemasonry shared the idea that politics should be based on the growth of individual development through stages of initiation. As Mazzini wrote in his Faith and the Future,

“How many stars, unravelled concepts of each epoch, must be raised in the sky of intelligence that Man, complete embodiment of the earthly Word, may say to himself: I have faith in myself; my destiny is accomplished?” (1)

Although, by definition, it is difficult to trace the influence of secret societies, the Carbonari are credited with winning constitutions in Spain and some states in Italy in 1820-21. They were also involved in the struggle for Greek independence and with the 1825 Decembrist rising in Russia. The Carbonari had a transnational view of politics and were willing to work wherever democratic ideals could be advanced, at times by armed revolt.

In 1834, Garibaldi participated in a failed military coup against the Duc of Savoie and was forced into exile in Latin America from 1836 to 1848. It was in Uruguay and Argentina that with Italian volunteers he organized a guerrilla force, the Red Shirts — modelled on the shirts worn in slaughter houses so as not to show the stains of blood. The militias of colored shirts were taken up by Mussolini and Hitler — a symbol of civilian unity outside the uniforms of military forces.

He returned to Italy in 1848 — the year of failed democratic revolutions. The Italian political movements could not decide on what type of Italy they wanted — federal or centralized, republican or monarchist. But the foundations of autocratic rule would never be the same again. By 1860-61, the power of Victor Emmanuel as King of Italy was established, though the real unity of Italy would take longer. The Papal states, an area going from Rome to the port of Ancona on the Adriatic and north as far as Bologna, were not yet integrated. It was in large measure Garibaldi who was able to unite the self-aggrandizement of the Piedmontese Government of Victor Emmanuel under the skilled leadership of Camillo Cavour with the progressive republicanism of Mazzini.

After the unification of Italy, his last military battles were with what he hoped would become Republican France against Prussia in 1870-71. The last 10 years of his life are those which made him the godfather of transnational democratic politics. From his island home of Caprera, off Sardinia, as president of the League of Democracy, he advocated a united democratic Europe, the emancipation of women, free education for all, the abolition of the death penalty, the end of the Papacy, and the independence of mind. His program followed closely that of his early Carbonari days, and he re-established his Carbonari-Freemasonry ties with the democratic forces of Europe.

Many major Italian movements, Fascism and Communism included, claimed Garibaldi as their ancestor. Only Planned Parenthood could not use him for their cause. The Italian state has used Garibaldi as a figure of Italian patriotism. However, as Max Gallo underlines in his biography Garibaldi, La force d’un destin, it is as a European with a policy of transnational politics, that Garibaldi stands out. From secret society, to ideological advocacy in the League for Democracy, Garibaldi experimented with many forces of transnational politics. While the use of force must be ruled out today, his other avenues may serve as inspiration as we develop new forces of democracy and justice.

NOTE:

(1) Quoted in E.E.Y. Hales Mazzini and the Secret Societies (New York: P.J. Kennedy & Sons, 1954).

__________________________________________

René Wadlow is a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Task Force on the Middle East, president and U.N. representative (Geneva) of the Association of World Citizens, and editor of Transnational Perspectives. He is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

René Wadlow is a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Task Force on the Middle East, president and U.N. representative (Geneva) of the Association of World Citizens, and editor of Transnational Perspectives. He is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Tags: Biography

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 29 Jun 2020.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Giuseppe Garibaldi (4 Jul 1807 – 2 Jun 1882): Godfather of Transnational Democratic Politics, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.