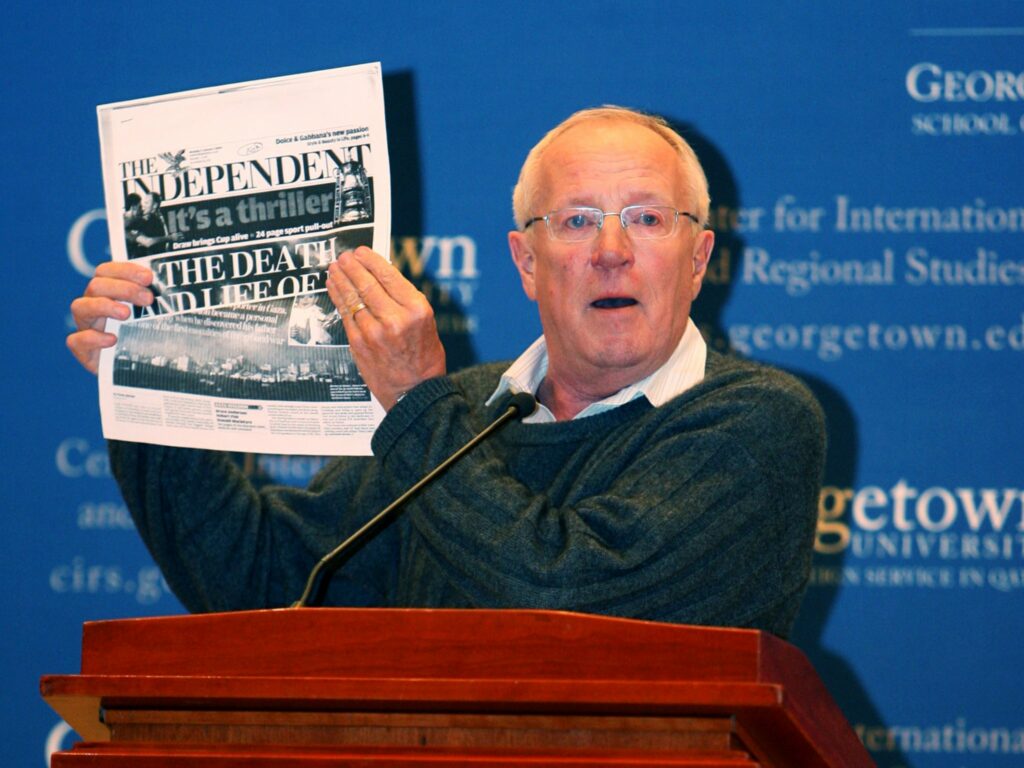

Robert Fisk of The Independent Has Died and Journalism Is Poorer

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 23 Nov 2020

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. – TRANSCEND Media Service

Tony Barber wrote an obituary in the Financial Times on November 6th:

“Robert Fisk, who has died at the age of 74, was one of his generation’s best-known foreign correspondents, admired for his indomitable courage and inimitable writing skills, but sometimes criticised for a lack of objectivity and exaggeration in his reports. His reputation rested primarily on his frontline coverage of wars and civil conflict in the Middle East and Islamic world. [ …. ] as he put it in 2010, “it is the duty of a foreign correspondent to be neutral and unbiased on the side of those who suffer, whoever they may be”. In practice he was an unrelenting critic of US and Israeli policies, a stance that increasingly coloured his work in the final 20 years of his career.”

“An unrelenting critic of US and British foreign policy (and French, and Israeli foreign policy)”? Tony Barber is paying Fisk a great COMPLIMENT: this is a description I would be proud to bear myself.

Was Fisk guilty of a “lack of objectivity and exaggeration” ???? I have often heard that said, but it simply means that he was an investigative journalist who described what he saw and what he heard. He actually did “investigations” rather than simply listening government spokesmen. He went into the field and took risks. Robert Fisk, unlike many whose bylines appear in newspapers (or even the famous BBC, whose anti-Alawite coverage of Syria – to take just one example – has been too one-sided to be called “impartial”), was unwilling to accept the official government line = propaganda put out by NATO member states and too often repeated as “news” quoting “unnamed government officials” or – as the New York Times loves to say – “citing senior officials requesting anonymity for speaking about security issues” or “on subjects they are not authorized to speak about.” Information … or propaganda?

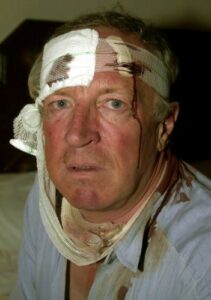

Good investigative reporters go to the front line, and they take risks. Fisk wanted to tell the stories of the victims. Robert measured the risks, and sometimes he misjudged the level of risk. That is a part of the job. Robert Fisk wrote stories that officials in comfortable Western embassies sometimes found uncomfortable.

Fisk took risks. He was dismissive of “hotel journalists” whose interviews are done by phone, or in the bar of a comfortable and secure hotel. I have often made similar criticisms about Western embassy and aid officials who only visit villages beside a tarmac road. I sleep in nomad tents and in villages with no water supply where I meet real people. If tarmac roads and 4WD vehicles provide your only vision of Africa, or Afghanistan, or Algeria – where Fisk reported on a vicious civil war during the 1990s – then your vision is bound to be distorted.

I am not saying that journalists should ignore government sources, or that they should not talk to opposition political leaders and government ministers in any country. I am saying that – like Robert Fisk – they need to get out into the streets and villages, meet other people and hear what is being said by those who live far from the capital city. Only then can outside observers present both sides of a political crisis, and that is what I call “impartial” analysis. As for pretending “objectivity”– that is rubbish. I used to tell my students in their first lesson of a semester, that “objective” is a word used by politicians and liars: who are often the same. We need active listening and the “subjectivity” of intelligent analysis based on experience, in order to approach the truth. Fisk did that very well.

A great many lies are fed to the media through the agencies AP, AFP and Reuters. Robert Fisk refused to repeat what other journalists were happy to take at face value. Fisk didn’t swallow the CIA’s version of Al Qaeda or ISIS, because he lived in Beirut and he had met Osama Bin Laden personally on three occasions, traveling to Tora Bora mountains to meet the Al Qaeda leader in a camp that the CIA had built for him to fight the Soviet army. Fisk was in a position to make his own independent and well-informed judgments.

Which explains why I regarded Robert Fisk as one of the most reliable sources of information and analysis of terrorism, political Islam, Middle East politics, and about the Modern Arab World – the title of a course I taught at Virginia Commonwealth University. I shall greatly miss Robert Fisk’s wisdom and understanding of the region. Most of the time I also agreed with Robert Fisk’s interpretation of Middle Eastern and World politics.

Tony Barber described how – while Robert was reporting from Belgrade on NATO’s 1999 military attacks on Yugoslavia – Yugoslav army officers pinned Fisk’s reports to a wall as an example of how foreigners should cover the war. As a supporter of Peace Journalism, I admired Fisk’s war reporting. He was not interested in reporting on the bullets; he was more interested in the victims and why they had become victims of violence. Not who? Or where? But WHY?

English and Irish by affiliation (he earned a PhD from Trinity College, Dublin and had an Irish passport) and born the same year as me, Robert Fisk made his name at The Times, where he worked from 1972 to 1989, before moving to The Independent, where he spent the rest of his career. Fisk died in Dublin on October 30. Michael D Higgins, Ireland’s head of state, said that with Fisk’s death “the world of journalism and informed commentary on the Middle East has lost one of its finest commentators”. I agree.

Fisk authored a large number of books, including some thriller novels. His magnum opus was The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East published in 2005 – a very long, and very depressing litany of British, French and American hypocrisy and biased Middle East policies with regard to the Arab–Israeli conflict, to Iran – and Fisk is not polite about the George Bush and Tony Blair invasion of Iraq in 2003. Fisk argues that the leaders of both countries deliberately misled the world about their motivations for invading Iraq in 2003.

Fisk authored a large number of books, including some thriller novels. His magnum opus was The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East published in 2005 – a very long, and very depressing litany of British, French and American hypocrisy and biased Middle East policies with regard to the Arab–Israeli conflict, to Iran – and Fisk is not polite about the George Bush and Tony Blair invasion of Iraq in 2003. Fisk argues that the leaders of both countries deliberately misled the world about their motivations for invading Iraq in 2003.

He is right. They lied. What is worse, many of us – including me – knew that they lied, wrote that they lied, and predicted appalling consequences including the destruction of Iraq and Syria, the end of democracy in Turkey and the creation of a mass migration of refugees into Europe. Are refugees a problem for Europe? Of course they are. And who created the refugee problem? Mainly Europeans.

Robert Fisk was an amusing and insightful speaker with great timing. From some of his interviews, I have culled a few precious quotations:

ON humanity:

In Oman it’s said, “If you see another man, he’s either your brother in religion

or your brother in humanity.” That officially is what we in the West believe; but I don’t think we practise it.

ON being a Journalist and Foreign Correspondent:

“I had a long conversation with Amira Hass, that very fine Israeli journalist who works for Ha’aretz, often reports from Ramala, and whose reports are more eloquent and more courageous than any of those of other western reporters in the Middle East. And she said, after I gave my very British definition of being a foreign correspondent (about how our job is to write the ‘first pages of history’), she said “no, Robert, you’re wrong. Our job is to monitor the centers of power; to challenge authority, especially when it wants to go to war, especially when it’s going to kill people, and especially when it tells lies.” “Notre rôle est de surveiller les cetres du pouvoir; de contester l’autorité, surtout s’il s’agit de la guerre, surtout quand il s’agit de tuer des gens et de mentir.”

And I thought that was the best definition I’ve ever heard of our job, or what our job should be. C’était la meilleure définition de notre rôle, de ce que nous devons faire.

ON Osama Bin Laden and democracy:

It doesn’t matter what happens if Bin Laden is killed tonight. He’s already created the monster: it’s there. How do we deal with it?

You know, I think we go on about democracy – I don’t think we want democracy. We never wanted it. Vous savez, on parle de la démocratie mais je crois que nous n’avons jamais souhaité promouvoir la démocratie.

Even when there was a serious opposition, the Egyptian parliament in the 1930’s the British arrested all the opposition. When there was democratic opposition to French rule in Lebanon, all the cabinet members were arrested and chucked into prison in Rashia. So it became a tradition in the Arab World of going underground if you wanted to be in opposition, because if you were legally in opposition you’d be arrested. La tradition veut dans le monde arabe, qu’on se cache pour rentrer en opposition aux pouvoirs politiques: sinon, tous ceux qui les opposent par une voie légale se trouvent emprisonnés.

Those in Muslim Brotherhood can tell you about that in Egypt today. So, in a sense you see, I don’t believe that democracy is something we’re interested in. I think Arabs would like some of our democracy. I think they’d like a couple of boxes of human rights off our western supermarket shelves. But I think they’d also like another kind of freedom. I think they’d like freedom from us. Je crois que les Arabes aimeraient bien avoir deux paquets de nos droits civiques; mais surtout ils souhaiteraient bénéficier d’une liberté d’une toute autre nature: être libérés de nous.

ON the American Empire and America’s New Iron Curtain:

Robert Fisk interviewed a man in the Middle East. He said, “Can you tell me why the Americans” — he meant, special forces, air force, line troops, infantry, whatever — “why the Americans are now in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Algeria – the special forces now have a fortress in the southern Algerian Sahara – and Oman, Yemen, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait – and still in part of Saudi Arabia? Why are they there?” he asked. “Pourquoi, me demanda-t-il, pourquoi toutes ces armes et toutes ces bases américaines – un véritable rideau d’acier – pourquoi sont-elles là?”

And indeed, you can go further north, Fisk observes. You can start in Greenland, Iceland, Britain, Germany, Bosnia -Yugoslavia now of course – Italy, Greece, and it all joins up at Turkey. From the Arctic Icecap to the borders of Somalia, there is now a continuous American Iron Curtain. In Pakistan too. Why?

What lies on the other side? India, China, Russia.

Why is that line there? What is that Iron Curtain for? I’m not sure of the answer, but these are the questions we should be asking. Instead of worrying about how many people were killed at Tal Afar, however important that may be. [Tal Afar is a town in Iraq where a bomb blast had killed 52 people or more just before this particular lecture.]

ON The Great War for Civilisation:

The name of Robert Fisk’s book comes from the Victory Medal, a United Kingdom and British Empire campaign medal, awarded to Fisk’s father for his services in the First World War 1914-18. Most of the borders of the modern Middle East were created by the British, French and Americans after WWI, by splitting up the Ottoman Empire. How many people discussing politics and elections in the pubs of US or UK understand that vital fact? How many of them know that Iran began its own internal, national, democratic experiment which was destroyed by a coup d’état engineered by the CIA and MI6 in 1953, ending with the death of Iran’s most popular politician: the elected Prime Minister Mohamed Mossadegh? Who believes that Western democracies are really trying to export “democracy?” Any rational study of Western foreign policy shows that we are mainly exporting weapons, mainly to support dependent dictatorships friendly to our business interests. “N’importe quelle étude sérieuse trouverait que nous n’exportons pas la démocratie: nous exportons des armes pour appuyer les dictateurs qui sont favorables à nos industries.”

ON our relationships with the Arab lands:

One of the conclusions I reached at the end of the book is how – and this was a more difficult message to pass across to audiences in the United States – how restrained Muslims had been towards us, given the cloak and blanket of injustice, which lay across their lands. Partly, we weren’t totally culpable; but we were very culpable because of our support for their dictators, because of our support, indeed our appointment and anointment of their dictators. [ …. ] As long as they obeyed the rules, the dictators were our friends in the region and we cared nothing about torture, or justice, or democracy. So I am left, still, at the end of the book, amazed that we have been visited so little violence by this part of the world. “A la fin de ce livre, je me trouve étonné que nous Occidentaux avons été si rarement victimes de violences faites par les peuples qui vivent au Moyen Orient.”

ON writing The Great War for Civilisation:

I found that writing of this book a very depressing experience. I never want to write a book like this again. It’s a very unhappy book.

J’ai trouvé fort déprimant l’écriture de ce livre. A l’avenir je ne souhaite jamais écrire un livre de la sorte. C’est un livre plein de malheurs.

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East is a book published in 2005 by the English journalist Robert Fisk. The book is based on many of the articles Fisk wrote when he was serving as a correspondent in the Middle East for The Times and The Independent.

__________________________________

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment and an independent researcher associated with UNIDIR-UN Institute for Disarmament Research and with the education association Virginia Friends of Mali. Poulton is the founder of the EPES Mandala Peace Consultancy. He is a sometime faculty member of the European Peace University (Austria), an Affiliate Research Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, and a consultant advisor on Africa to governments, the U.N. and the European Union. Poulton is a specialist in terrorism, disarmament, conflict transformation and peace building having 25 years of field experience with UNDP, EU, USAID and NGOs. He is the author of several books in French and English on development and disarmament. He received his Ph.D. from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, France. repoulton@epesmandala.com

Robin Edward Poulton, Ph.D. is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment and an independent researcher associated with UNIDIR-UN Institute for Disarmament Research and with the education association Virginia Friends of Mali. Poulton is the founder of the EPES Mandala Peace Consultancy. He is a sometime faculty member of the European Peace University (Austria), an Affiliate Research Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, and a consultant advisor on Africa to governments, the U.N. and the European Union. Poulton is a specialist in terrorism, disarmament, conflict transformation and peace building having 25 years of field experience with UNDP, EU, USAID and NGOs. He is the author of several books in French and English on development and disarmament. He received his Ph.D. from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, France. repoulton@epesmandala.com

Tags: Investigative Journalism, Journalism, Mainstream Media MSM, Media, Obituary, Robert Fisk

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 23 Nov 2020.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Robert Fisk of The Independent Has Died and Journalism Is Poorer, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.