Defending Our Sovereignty: US Military Bases in Africa and the Future of African Unity

AFRICA, 12 Jul 2021

Tricontinental - TRANSCEND Media Service

5 Jul 2021 – How do you visualise the footprint of Empire?

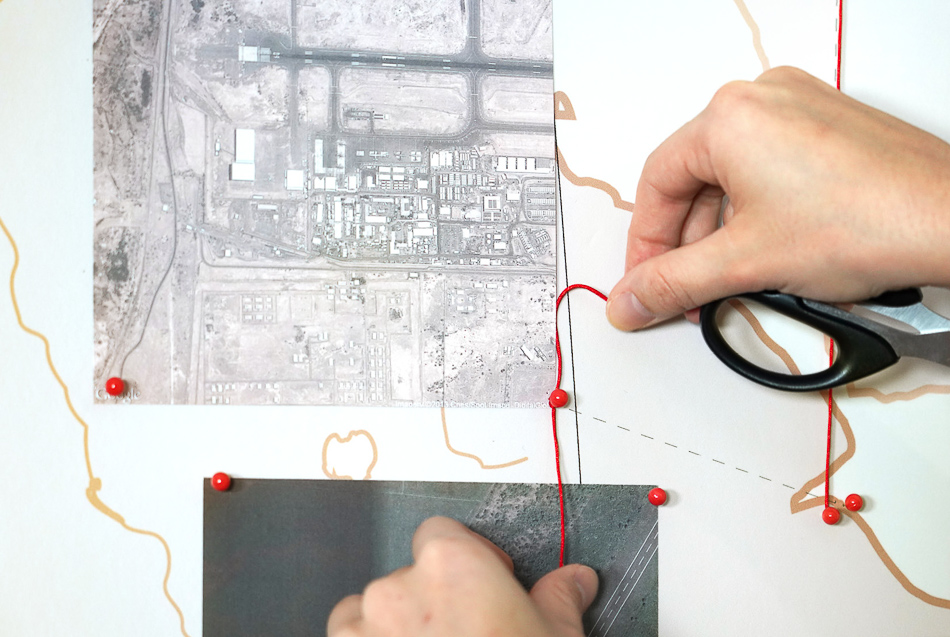

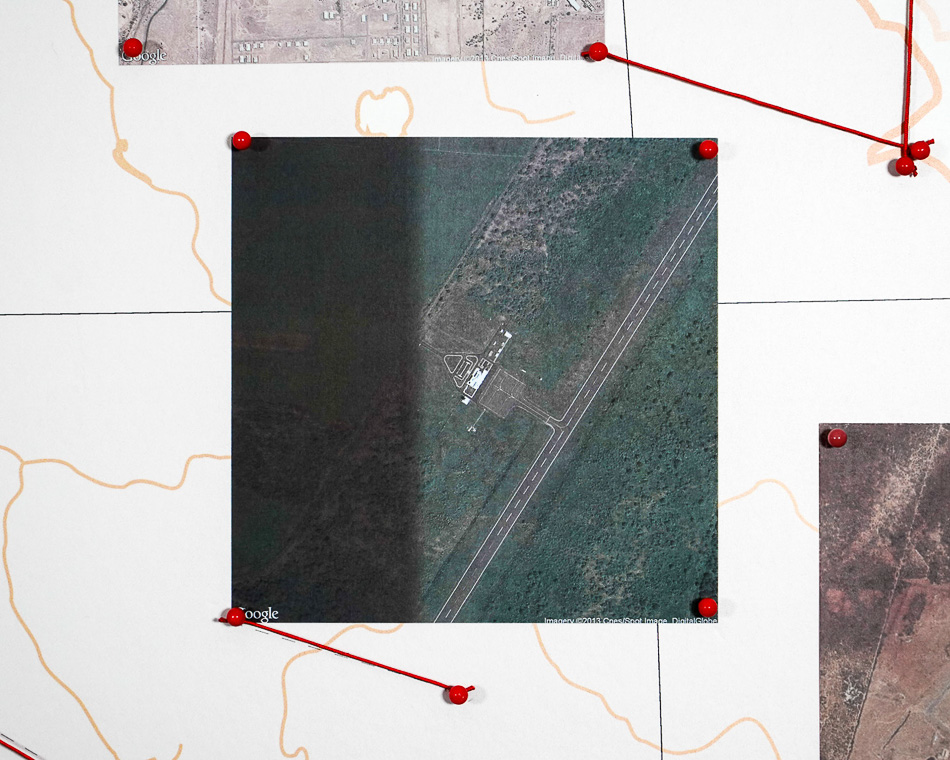

The images in this dossier map some of AFRICOM’s military bases on the African continent – both ‘enduring’ and ‘non-enduring’, as they are officially called. The satellite photos were gathered by data artist Josh Begley, who led a mapping project to answer the question: ‘how do you measure a military footprint?’

For this dossier, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research physically projected images and coordinates of these hidden-away sites onto a map of Africa, visually reconstructing the apparatus of militarisation today.

Meanwhile, the pins and thread connecting these places remind us of the ‘war rooms’ of colonial domination. Together, the set of images is a visual testament to the continued ‘fragmentation and subordination of the continent’s peoples and governments’, as this dossier writes.

We refuse simple survival. We want to ease the pressures, to free our countryside from medieval stagnation or regression. We want to democratise our society, to open up our minds to a universe of collective responsibility, so that we may be bold enough to invent the future. We want to change the administration and reconstruct it with a different kind of civil servant. We want to get our army involved with the people in productive work and remind it constantly that, without patriotic training, a soldier is only a criminal with power. That is our political programme.

Thomas Sankara (President, Burkina Faso) at the United Nations, 4 October 1984.

On 30 May 2016, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) held its 601st meeting. Though the agenda was broad, members of the PSC came to the meeting concerned about a range of conflicts: the collapse of the Libyan state and the impact that this had across the Sahel, the ongoing struggles in the Lake Chad region with the persistence of Boko Haram, and the wars that marked the Great Lakes region (with the loss of sovereignty by the Democratic Republic of the Congo on its eastern flank). The ‘primary responsibility for ensuring effective conflict prevention’, the PSC noted, ‘lies with the Member States’, namely the fifty-five countries on the African continent from Algeria to Zimbabwe.

The PSC needed no lessons from anyone on its own limitations, which were two-fold:

- Internal fragmentation. Only months before the May meeting, the PSC had authorised the deployment of 5,000 troops from the African Prevention and Protection Mission to Burundi. This was partly due to the enduring causes of the long-standing conflict in the Great Lakes, which included the Burundian Civil War (1993-2005) as well as the political crisis occasioned by President Pierre Nkurunziza’s suffocation of the political system, which led to public protests and state repression in 2015. President Nkurunziza pushed an agenda amongst African heads of governments to block the PSC’s decision. The AU decided that the situation in Burundi had calmed down, despite the fact that the United Nations found evidence of crimes against humanity. This was one example of the fragmentation of the African leadership, which prevented the PSC from moving an agenda.

- External pressures. In February-March 2011, the PSC met to draw up a full-fledged roadmap to dial back the conflict in Libya. A PSC mission gathered at Nouakchott, Mauritania to travel to Tripoli, Libya and open negotiations based on paragraph 7 of the PSC communique. This paragraph – which was known as the ‘roadmap’ – contained an elegant four-point pathway, including the cessation of hostilities, delivery of humanitarian assistance through cooperation, protection of foreign nationals, and adoption and implementation of political reforms to eliminate the causes of the crisis. Both the government of Libya and the opposition initially rejected the roadmap, but the avenues for dialogue remained open, which is why a PSC mission was ready to go to Tripoli. The day before the PSC mission could leave, France and the United States began to bomb Libya. This bombing took place under the aegis of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and UN Security Council resolution 1973 (voted on by three African countries: Gabon, Nigeria, and South Africa). The ‘humanitarian intervention’ quickly exceeded the UN mandate of protecting citizens, moving towards regime change using immense violence that resulted in civilian casualties. The disregard shown by the North Atlantic states for the African Union and the PSC has gone by virtually unremarked.

In the aftermath of the NATO war on Libya, the Sahel region experienced a number of conflicts, many of them driven by the emergence of forms of militancy, piracy, and smuggling. Using the pretext of these conflicts, and inflamed by NATO’s war, France and the United States intervened militarily across the Sahel. In 2014, France set up the G-5 Sahel, a military arrangement that included Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, and expanded or opened new military bases in Gao, Mali; N’Djamena, Chad; Niamey, Niger; and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The United States, for its part, built an enormous drone base in Agadez, Niger, from which it conducts drone strikes and aerial surveillance across the Sahel and the Sahara Desert. This is one of the many US bases on the African continent. The United States has twenty-nine known military facilities in fifteen countries on the continent, while France has bases in ten countries. No other country from outside the continent has as many military bases in Africa.

The number of foreign military bases on the African continent alarmed the PSC, which raised this as an important issue in its May 2016 meeting:

Council noted with deep concern the existence of foreign military bases and establishment of new ones in some African countries, coupled with the inability of the Member States concerned to effectively monitor the movement of weapons to and from these foreign military bases. In this regard, Council stressed the need for Member States to be always circumspect whenever they enter into agreements that would lead to the establishment of foreign military bases in their countries.

Since 2016, little advance has been made on the PSC statement. It is telling that the PSC did not name the countries that have the most bases on the continent, a question of quantity that has an impact of the quality of suppression of African sovereignty. Had the PSC named the United States and France as the main countries that have military bases in Africa, it would have had to acknowledge the particular reasons why the US and France continue to require a military presence for their ends.

It is important to acknowledge that these developments are neither the norm for Africa’s modern history nor are they inevitable. In 1965, Ghana’s former President Kwame Nkrumah published an important book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, which reflected on the phenomenon of military bases. These had been commonplace during the time of high colonialism, with bases across the continent from the British base at Salisbury in former Rhodesia (present-day Harare, Zimbabwe) to the French base at Mers El Kébir in Algeria. Both the British and the United States militaries had bases in Libya, from the Wheelus Air Base to the military posts in Tobruk and El Adem. In return for the land and the right to barrack troops at these places, the UK and the US provided Libya with ‘aid’, which Nkrumah rightly said was a payment for the loss of sovereignty. Here is Nkrumah’s assessment of these bases in Africa:

A world power, having decided on principles of global strategy that it is necessary to have a military base in this or that nominally independent country, must ensure that the country where the base is situated is friendly. Here is another reason for balkanisation. If the base can be situated in a country which is so constituted economically that it cannot survive without substantial ‘aid’ from the military power which owns the base, then, so it is argued, the security of the base can be assured. Like so many of the other assumptions on which neo-colonialism is based, this one is false. The presence of foreign bases arouses popular hostility to the neo-colonial arrangements which permit them more quickly and more surely than does anything else, and throughout Africa these bases are disappearing. Libya may be quoted as an example of how this policy has failed.

In 1964, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser called for the removal of these bases, and in 1970 – after Colonel Muammar Gaddafi overthrew the monarchy – the bases were removed. Five years before this, Nkrumah correctly judged the mood of the Libyan people. This mood, from 1965, runs through to the present. Since it was set up in 2007, the US government’s Africa Command (AFRICOM) has not been able to find a home on the African continent; the headquarters of AFRICOM is in Stuttgart, Germany. The African people continue to pressure their governments not to give in to US demands to shift the AFRICOM headquarters from Europe to Africa.

Neo-colonialism, Nkrumah noted, seeks to fragment Africa, weaken African state institutions, prevent African unity and sovereignty, and thereby insert its power to subordinate the aspirations of the continent for pan-African consolidation. Neither the Organisation of African Unity (1963-2002) nor the African Union (2002 onwards) have been able to realise the two most important principles of pan-Africanism: political unity and territorial sovereignty. The enduring presence of foreign military bases not only symbolises the lack of unity and sovereignty; it also equally enforces the fragmentation and subordination of the continent’s peoples and governments.

The Surrender of Our Sovereignty

In 2018, the US Department of Defense proposed that the US and Ghana agree to a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), a $20 million deal that would allow the US military to expand its presence in Ghana. In March, widespread unhappiness of this agreement swept large sections of the population into the streets; opposition parties, who worried about the possibility that the US would build a military base in the country, raised their objections in parliament. By April, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo said that his government had ‘not offered a military base, and will not offer a military base to the United States of America’. The US Embassy in Accra repeated this statement, saying that the ‘United States has not requested, nor does it plan to establish a military base or bases in Ghana’. The SOFA agreement was signed in May 2018.

It does not require a close reading of the agreement’s text to know that there is in fact the possibility that the US could build a base in the country. Article 5, for instance, states,

Ghana hereby provides unimpeded access to and use of Agreed facilities and areas to United States forces, United States contractors, and others as mutually agreed. Such Agreed facilities and areas, or portions thereof, provided by Ghana shall be designated as either for exclusive use by United States forces or to be jointly used by United States forces and Ghana. Ghana shall also provide access to and use of a runway that meets the requirements of United States forces.

Through this article, the US is permitted to create its own military facilities in Ghana. By any definition, this means that it can set up a base. The surrender of Ghana’s sovereignty also comes to light where the SOFA agreement states (Article 6) that the US would ‘be afforded priority in access to and use of Agreed facilities and areas’ and that said use and access by others ‘may be authorised with the express consent of both Ghana and United States forces’.

TO CONTINUE READING Go to Original – thetricontinental.org

Tags: Africa, Africom, Anglo America, Anti-militarism, Arms Industry, Arms Race, Conflict, Geopolitics, Hegemony, History, Human Rights, Imperialism, International Relations, Military, Military Industrial Complex, Military Industrial Media Complex, Military Intervention, Military Supremacy, NATO, Pentagon, Politics, Power, US Military, USA, Violence, War, War on Terror, World

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.