The Muezzin’s Call

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 29 Nov 2021

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

An Odyssey of Peace and Spirituality of the Minority “Zanzibari” in South Africa

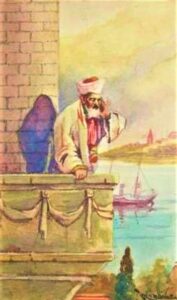

24 Nov 2021 – In Islam, Muslims are called to the five scheduled daily prayers by a formal announcement, called the azaan. This vocal call to prayer, from the mosque, is made by a specially appointed person, called the muezzin[1], who stands either in the mosque’s minaret tower if the mosque is large or in a side area if the mosque is small. This call is analogous to the ringing of bells, inviting the congregants to a prayer service in a church, in Christianity. In Judaism, a trumpet is used to summon the devotees to the Shul, while in Islam the human voice is utilized to invite the followers to the mosque for the daily prayers.[2]

The Muezzin, is therefore an Islamic religious official who proclaims the call to prayer, the azaan, for the public worship on a Friday, at midday and the call to the daily prayers, five times a day, at dawn, noon, midafternoon, sunset, and nightfall. The muezzin is the servant of the mosque and is chosen for his good character. He stands either at the door or side of a small mosque or climbs up to the top of a platform of the minaret of a large one. He faces each of the four compass directions in turn: east, west, north, and south. To each direction he vocalises the Azaan, also spelt Adhan is the Islamic call to Prayer. The English translation of the adhan is:-[3]

God is Great! God is Great! God is Great! God is Great!

I bear witness that there is no god except the One God.

I bear witness that there is no god except the One God.

I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God.

I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God.

Hurry to the prayer. Hurry to the prayer.

Hurry to salvation. Hurry to salvation.

God is Great! God is Great!

There is no god except the One God.

Many mosques have installed high-powered public-address systems, as in the Grand Mosque in Mecca, to relay the call to prayers without the Muezzin having to climb the spiral steps of the traditional minaret of the mosque with amplifiers. While the modern electronic can be used, it is traditional to use the physical services of the Muezzin, in most mosques. The prayer or salah, performed prior to sunrise at dawn, has a slightly extended version to the Azaan in which the devotee is invoked to wake up and come to the mosque for congregational prayer, which is compulsory for all Muslims, five times a day.[4] The additional words in the predawn azaan are “prayer is better than sleep”, appealing to the followers of Islam to come to the prayer. The azaan, by the Muezzin, is aimed at reaching everyone who practices Islam. But some countries have taken measures to ban the recital of the Azaan on loudspeakers.[5]

It is also interesting to note how the azaan, as a call to prayer originated in Islam. In the early days of Islam[6]. The origin of the adhan is traced back to the foundations of Islam in the seventh century. There was no prescribed way of informing the followers of Islam, that the time for prayer had commenced, nor was there any means to call Muslim worshippers to the mosque for congregational prayers. Prophet Muhammad was, however, aware of the Jewish, Christian and pagan practices in this regard. He sought counsel and asked his companions what should be done to call Muslims to the mosque for congregational prayers. “One morning, Hazrat Umar Abdullah ibn Aziz[7] approached the Holy Prophet and related to him a dream which he had had the night before. He had seen someone announcing the prayer time and calling people to the mosque for the congregational prayer in a loud voice. Hazrat Umar Abdullah then related the words of the Azaan which he had heard in the dream,”

The very first muezzin in Islamic history, was a slave named Bilal ibn Rabah[8], the son of an Arab father and an Ethiopian mother, who was a slave. Bilal who was born in Mecca in the late 6th century. Bilal was one of the earliest converts to Islam, but his owner tried to get him to renounce Islam by subjecting him to a series of torturous punishments. When his story became known, one of the Prophet Muhammad’s[9] followers, Abu Bakr[10], who later became the first caliph, bought him and set him free.

At about the same time, the number of people accepting Islam was growing. The number of prayers during a day seems initially to have been three, but later became five, but without clocks as we know them, the duty of praying together as a community was becoming difficult. One suggestion seen in a dream was to use a wooden clapper, a device found among the Christians; however, the man in the dream suggested the Muslims have someone vocalize the call to prayer, the adhan in Arabic. This proposal found favor with the Prophet Muhammad and he suggested Bilal, who was known for his mellifluous voice. In the dream, the words to be recited were given stated above, in English.

Bilal went to Medina in 622 with the Prophet Muhammad and from then on served as his mace or spear bearer and steward on the various military expeditions that the latter undertook. As his steward, he was responsible for the whole treasury of the Muslims and distributed funds to widows, orphans and others in need. The Muslim forces captured Mecca and in January 630, Bilal climbed to the top of the Kaaba[11] to sound the call to prayer there for the first time. The sources are not clear about what happened to Bilal following the death of the Prophet in 632. One report suggests that he continued to act as muezzin for the first Caliph Abu Bakr, but refused to do so for the second caliph[12]. Another source notes that he only sounded the call to prayer twice more – once in Syria at the request of the second caliph, Omar and again in Medina because the Prophet’s grandsons asked him to do so. Bilal died at some time between 638 and 642 and was buried in Syria or in Jordan, depending on which source you believe. He is honored as the first muezzin by both Sunni[13] and Shia Muslims. [14] and in keeping with that tradition, the muezzins in most mosques are persons of African origins.

Bilal started the tradition of sounding the call to prayer from a rooftop but, as Islam spread, the idea of building a tower for the muezzin appeared.[15] The first minarets have been dated from 673, although they might have been built somewhat later. They come in various shapes and materials, such as brick or dressed stone depending on the local culture. The interior, though, had to be hollow in which a staircase for ascending and descending ensured that the muezzin could reach the balcony from which to give the call to prayer. The stone steps were high and narrow; worn down over time and they are difficult to climb, so it’s not surprising that using loud speakers from the ground has gained favor. Only a very few throughout the Muslim world have stairs on the outside.

Traditionally, mosques in the Ottoman Empire had only one minaret with the exceptions being the so-called imperial mosques. These were built in Edirne[16] and Istanbul at the command of the sultan of the time. The four minarets at the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne are among the slimmest and highest ever built and have three balconies. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul has an unconventional six.

Muezzins with exceptionally beautiful voices sometimes achieve minor celebrity status, with worshipers traveling great distances to their mosques in order to hear their renditions of the adhan[17].

In South African mosques, it is traditional to employ an African person as a Muezzin, principally in keeping with the historic tradition and more importantly, these Muezzins have a melodious and loud voice, as did Bilal, the first muezzin of Islam. These muezzins are highly respected and spiritual individuals and in South Africa they mainly belong to the small, self-contained “Zanzibari” community.

The Zanzibaris were first classified by the South African Government as “Freed Slaves”, then “Bantu”, then “Coloureds” and finally by the Race Classification Proclamation No 6620 of 1961,-the Zanzibaris living in South Africa were classified as “Other Asiatics”, although they have always had their roots in the African continent.[18]

South Africa’s tight-knit Zanzibari community is not actually from Zanzibar, at all. They originated and are the descendants of freed slaves from Mozambique. Canthitoo is one of thousands of descendants of freed northern Mozambican slaves, known as the Makua people, brought to South Africa, Durban, by the British in the 1870s after they intercepted illegal slave ships en route to Zanzibar with captured slaves as cargo.[19]

The history of the ‘Zanzibari’ community in Durban, made up of people of predominantly northern Mozambican descent, provides an extraordinary illustration of the cultural linkages forged across the Indian Ocean, as well as of the particular importance of transnational Sufi Islamic networks in maintaining such linkages. The Indian Ocean slave trade not only involved the Cape, as documented by previous historians, but also encompassed the present-day area of KwaZulu-Natal. The history of Durban’s Zanzibari community highlights the diverse ways in which descendants of freed slaves in Southeastern Africa harnessed the power of religion to give meaning to their lives amid dramatic processes of social change. In response to shifting politics in South Africa and further afield, they engaged Islamic and Sufi ritual and networks to craft and codify stories-of-origin that promoted internal cohesion, respectability, and community progress.

At times, Zanzibaris emphasized their cosmopolitanism as members of an Indian Ocean world and, at other times, they focused on more narrowly defined ties to discrete territorial locations in South Africa and Mozambique.[20] These “Zanzibaris” were people of Mozambican origins and their religion as Islam. They settled in Kings Rest[21] on the Bluff on the bar of land shielding Durban’s natural harbour from the Indian Ocean along the eastern seaboard of South Africa. Their removal from their original settlement on the Bluff, by the group areas act promulgated by the apartheid, nationalist government in 1948, to the new Indian township of Chatsworth, caused a great deal of unhappiness. However, this community, fifteen years ago, won back land they lost in Durban under South Africa’s apartheid regime. The land is presently prime real estate in the city of Durban’s lucrative tourist market.[22]

The Early History of the Zanzibaris in Durban

The Zanzibari community developed from a group of 508 liberated slaves, who were brought to Durban as indentured labourers in the 1870s and 1880s. The majority were Makua-speakers, freed by British Navy vessels off the northern Mozambican coast en route to slave markets in Madagascar or Pemba.[23] Although most were taken to Durban by the British Navy, some went first to Zanzibar, the site of the headquarters of the British antislavery campaign. In Durban, they were advertised to labour-hungry settlers in local newspapers as ‘Liberated Africans from Zanzibar’. The Muslim majority of these freed slaves appropriated the name of ‘Zanzibaris’, marking themselves as distinct from local Zulu-speaking Africans. By contrast, a Christian minority among the freed slaves gradually becoming absorbed into the Zulu-speaking population.[24]

At the end of indenture, both groups came under the wings of missionaries and were settled on the Durban Bluff by a ‘Mohammedan Trust’ of Sunni and Barelwi businessmen with links to the Jumma Musjid mosque on Grey Street,[25] and by the Catholic St Francis Xavier’s Mission.[26] The contrasting paths of these liberated slaves – one group choosing to identify themselves as Zulu-speakers, the other group emphasizing their provenance from Zanzibar – corresponded to competing religious strategies operating in Natal in this period: Catholic missionaries’ expansionary drive on one hand, Muslim efforts to gather a faithful minority on the other.[27]

However, the identification of the former slaves as Zanzibaris, rather than as ‘natives’ or ‘Africans’, was tested in 1937–8, when a Zanzibari named Hassan Fakiri was convicted for evading the poll tax, which all Africans were obliged to pay. With the financial and legal backing of the Jumma Musjid Trust, Fakiri appealed the decision. As the grandchild of freed slaves who came from Zanzibar, a Muslim, and a ‘Swahili’-speaker, Fakiri stated that he was not ‘a Native within the definition of the legislation’, that is, not a member of ‘an aboriginal tribe or race of Africa’.[28] The case was lost but it demonstrated the possible political implications of Zanzibari identity: by figuring Zanzibar as outside of ‘aboriginal’ Africa and its inhabitants as ‘descendant of Arabs’, Fakiri could claim that he was not a ‘Native of Africa’.[29]

Zanzibari exceptionalism came to the fore in the high apartheid period of the 1950s, when the regime’s efforts to categorize the population according to race reached its peak. In 1961, Zanzibaris were reclassified under the Population Registration Act – another central piece of apartheid legislation, as ‘Other Asiatics’. This meant that their forced removal in 1962–3 under the Group Areas Act, when the Bluff became a ‘white’ area, took them, not to the African township of Umlazi on the southern outskirts of Durban, but to Bayview (Unit Two) of the neighbouring Indian township of Chatsworth.

Though the move meant the loss of proximity to Durban’s central business district, it affirmed Zanzibari claims to being ‘non-native’, and enhanced opportunities for pursing education and achieving respectability. Because of its relative autonomy and the strength of its religious organisations, the Zanzibari community had long been a magnet for African Muslims visiting Durban, either as sailors or as migrant labourers from neighbouring countries. It also became a model for other African Muslim groups in the greater Durban area, and from the 1930s, African Muslims, mainly from Malawi, began to establish ‘Zanzibari’ societies in settlements like Marianhill and Amaoti.[30] at the same time, members of the Zanzibari community served as religious instructors and teachers of Arabic in African townships.[31]

Makua language and traditions have figured prominently in Zanzibaris’ cultural entrepreneurship projects. Together with a particular dedication to Islam, the Makua language became a key marker of Zanzibari identity. This emphasis upon language gained new significance as the community came to incorporate new members, including poor Indian families as well as immigrants from Mozambique, Malawi, and Zambia. Such heterogeneity was nothing new; even the original group of 508 liberated slaves included a significant minority whose native languages were Ngindo and Yao rather than Makua. In the late nineteenth century, however, an extensive Makua diaspora emerged through the dispersal of slaves and freed slaves across the Western Indian Ocean region.

Indeed, Makua may have been a lingua franca among the liberated slaves when they arrived in Durban in the 1870s. Thus, in her research on slave descendants in Madagascar, Klara Boyer-Rossol found that Makua had been spoken among different groups of slaves held on the African coast prior to their transportation across the Mozambique Channel.[32] in most of the Makua diasporas that have been documented in the Western Indian Ocean, including Somalia, Reunion, and Madagascar, the Makua language has been lost, importantly due to its association with slave status.[33]

The Zanzibari community, in turn, embraced forms of Islam that could accommodate Makua cultural practices. In accordance with matrilineal traditions, women played prominent roles in the community, and girls and boys underwent elaborate ritual initiations.[34] Oosthuizen offers a syncretist interpretation of such practices as examples of ‘indigenous Islam’, in which traditional African customs and Islam merged into one another so that it is not easy to discern between the two at any given point’.[35]

Sufism became an important influence among the Zanzibaris through three different trajectories: one coming across the Indian Ocean from South Asia,[36] another through Cape Town from Indonesia and the Malay world,[37] and a third trajectory which extended down the Indian Ocean coast from Zanzibar and the Comoros through northern Mozambique to Durban.[38] One set of Sufi influences on the Zanzibaris in Natal came from interaction, beginning in the early 1880s, with Indian Muslims in Durban; that is, with representatives of the first of the three trajectories. Particularly influential were the group of Indian businessmen who controlled the Grey Street mosque and the Jumma Musjid Trust.[39]

As apartheid[40] governance crumbled in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the challenges facing Zanzibaris changed. Representations of the community as non-African Muslims with their own Swahili-like language proved advantageous under the Group Areas Act. In the context of the Act’s forced removals, it was a political achievement to be classified as ‘Other Asiatics’ and awarded housing and facilities in Chatsworth rather than in Umlazi. After apartheid, by contrast, policies of the African Renaissance and Black Economic Empowerment made recognition as black African more politically and economically advantageous.

Thus, it became increasingly common for Zanzibaris to present themselves as ‘Amakhuwa’, and locate their Indian Ocean roots in northern Mozambique rather than Zanzibar. As part of constructing an Amakhuwa identity, Durban Zanzibaris have emphasized their preservation of the Makua language, their Sufi faith, and their slave history. Such emphasis aims not to claim external origins but to give depth and authenticity to their South African citizenship and its attendant rights. This strategy resembles that of ‘Cape Malay’ groups in post-apartheid South Africa who claim to be both South African and members of a Malaysian or Indonesia diaspora.[41]

The coming years will tell how Zanzibaris resolve or do not resolve these tensions in their self-representations and commemorations of the past. These are not theoretical issues but practical ones that will play out as the land restitution project on the Bluff moves forward. In a sense, the restitution project is an attempt to turn history backwards by recreating a community that was forcefully dismantled fifty years ago. Restitution in such a literal sense is, of course, not possible as many members and descendants of the original community have since died or moved away. Nonetheless, it compels community members to decide how they want their history as Zanzibaris and Amakhuwa to be represented in local archives and museums, and through educational and heritage tourism initiatives.

This complex history of identity formation and self-representation highlights a number of issues that have been largely overlooked in the literature on Islam in both South and Southeastern Africa. These include the importance of Sufi brotherhoods and ritual for the development of Islam among Africans, particularly in Durban and KwaZulu-Natal. This history also highlights the interaction between the three different trajectories by which Sufism travelled to South Africa: with migrants from South Asia; with other migrants from Malaysia and Indonesia who settled in Cape Town; and with still a third set of migrants who travelled down the Indian Ocean coast from Zanzibar and the Comoros through northern Mozambique to Durban. The connectedness of Durban’s Zanzibaris to Mozambican networks challenges notions of South African ‘exceptionalism’ by providing a new perspective on the ways in which South Africa has been part of an Indian Ocean coastal continuum. Finally, this history of Durban’s Zanzibaris adds to the growing number of studies that examine the large and diverse Makua diaspora that arose from the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century slave trade.

The two modes of communal self-understanding – Zanzibari and Amakhuwa, point to a tension between the local and the transnational, uneasiness found in other Indian Ocean situations. As shown, membership in Indian Ocean and specifically Sufi religious networks can serve as a basis for both cosmopolitan connection and narrow territorial claims. The particular paradox involved in this case is that cosmopolitanism, as represented in arguments for membership in an Indian Ocean Zanzibari community, aided this group during segregation and apartheid, eras normally associated with a narrowing and hardening of forms of self-identification. By contrast, the narrower territorial understanding of the community’s origin in northern Mozambique emerged after the fall of apartheid in South Africa and the weakening of secular nationalism in Mozambique, shifts usually associated with multiculturalism and greater tolerance. Whether deployed as part of cosmopolitan connection or narrow territorial claims, Sufi networks offered vital resources for seeking recognition and citizenship.

The Bottom Line is that post-apartheid, the “Zanzibari” community regained their original land and today, their long odyssey has progressed from freed slaves to highly respected members of the Islamic community in South Africa. The community has empowered itself and opened up training centres where the young children are educated, proceeding up to tertiary levels of education in South Africa. In addition, most mosques in Southern Africa have highly qualified “Zanzibari” Muezzins, not only vocalising the Islamic call to prayer, but are also senior theologians and Hafez’s who are hafezs’[42] memorised the Quran, but also know the Arabic language to converse freely with visitors to South Africa from the Middle East.

These are the “Sheiks” as a title of respect. There are numerous such Sheiks throughout the country, but one person which needs special mention is Sheik Elias Balala[43], who although is not a direct descendant of the Mozambican slaves, but as a group, he is the Muezzin of the new mosque in the upmarket suburb of Musgrave in Durban South Africa. He has obtained his Islamic training in the city of Prophet Muhamad, Medina[44] and knows several languages, including Arabic, has led the main prayers in the Masjidus Salaam[45] (The Mosque of Peace).

Sheik Balala has on numerous occasions, in the absence of the Chief Priest, the Imam of this mosque. He is a living example of incorporating enculturation, with his traditional upbringing and the good western influence. Their original cultural practices, tradition and language are maintained and sustained and these so called “Zanzibaris” have maintained their identity, without the negative influences of the western civilization, which has also affected South Africa, leading to moral degeneration and spiraling into an abyss of vice, corruption at highest levels of the ruling party, government, drug addiction, uncontrolled HIV infection, crime, brutal farm murders, rampant violence, corrupt police force and gender based abuse which has affected the indigenous African people, post-apartheid, turning South Africa into a “Mafia State”. Essentially, the South African transformation consists of the Indian population imitating the White, the African population imitating the Indian, losing their respected cultural origins and identities and the Whites are simply leaving the country by emigrating to Australia, New Zealand and North America or Middle East.

References:

[1] https://www.google.com/search?q=muezzin+definition&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Muezzin&aqs=chrome.2.0i512l7j69i60.5348j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=The%20muezzin%20is%20the%20person%20who%20proclaims%20the%20call%20to%20the%20daily%20prayer%20five%20times%20a%20day%20at%20a%20mosque.%20The%20muezzin%20plays%20an%20important%20role%20in%20ensuring%20an%20accurate%20prayer%20schedule

[2] https://www.britannica.com/topic/muezzin#:~:text=muezzin%2C%20Arabic%20mu%CA%BEaddin,mosque%20and%20is

[3] https://www.learnreligions.com/what-do-the-words-of-the-adhan-mean-in-english-2003812#:~:text=The%20Adhan%3A%20The%20Islamic%20Call%20to%20Prayer

[4] https://islam.stackexchange.com/questions/10590/why-is-assalatu-khairum-minan-naum-only-said-in-the-fajr-morning-azan-call-for

[5] https://www.iol.co.za/thepost/news/loudspeakers-in-mosques-debate-echoes-globally-e1a27d41-7633-4f1c-b5b9-ee40f0c6a322#:~:text=THE%20Azaan%2C%20or,Azaan%20on%20loudspeakers.

[6] https://www.google.com/search?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.al-islam.org+Origin+of+Azaan&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.al-islam.org++Origin+of+Azaan&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i58.7080j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=the%20ritual%20of%20the%20adhan%20is%20traced%20back%20to%20the%20foundations%20of%20Islam%20in%20the%20seventh%20century.%20…%20When%20Bilal%20first%20called%20the%20adhan%2C%20%27Umar%20bin%20Al%2DKhattab%2C%20who%20later%20became%20the%20second%20caliph%2C%20heard%20him%20in%20his%20house%20and%20came%20to%20Prophet%20Muhammad%20saying%20that%20he%20had%20seen%20precisely

[7] https://www.google.com/search?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.al-islam.org+Origin+of+Azaan&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.al-islam.org++Origin+of+Azaan&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i58.7080j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=When%20Bilal%20first%20called%20the%20adhan%2C%20%27Umar%20bin%20Al%2DKhattab%2C%20who%20later%20became%20the%20second%20caliph%2C%20heard%20him%20in%20his%20house%20and%20came%20to%20Prophet%20Muhammad%20saying%20that%20he%20had%20seen%20precisely%20the%20same%20vision%20in%20his%20dreams.

[8] https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/the-history-of-the-muezzin–74007#:~:text=The%20very%20first,adhan%20in%20Arabic).

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad

[10]https://www.google.com/search?q=hazrat+abu+bakr+services+to+islam&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Hazarath+Abu+Bakr&aqs=chrome.8.69i57j46i13j0i13l7.17821j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=Bakr%20was%20a%20senior%20companion%20(Sahabah)%20and%20the%20father%2Din%2Dlaw%20of%20the%20Islamic%20Prophet%20Muhammad.%20He%20ruled%20over%20the%20Rashidun%20Caliphate%20from%20632%2D634%20CE%20when%20he%20became%20the%20first%20Muslim%20Caliph

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaaba

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umar

[13] https://www.google.com/search?q=Sunni&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Sunni&aqs=chrome.0.69i59.502112j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=A%20Sunni%20is%20a%20member%20of%20the%20largest%20branch%20of%20Islam.%20A%20Sunni%20is%20a%20Muslim%20who%20believes%20that%20the%20caliph%20Abu%20Bakr%20was%20the%20rightful%20successor%20to%20Muhammad%20after%20his%20death.%20There%20are%20several%20different%20traditions

[14] https://www.google.com/search?q=Shia+Muslims&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Shia+Muslims&aqs=chrome..69i57.632658j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=make%20up%20around%2015%20percent%20of%20Muslims.%20The%20early%20Shias%20rejected%20the%20authority%20of%20Mohammed%27s%20successor%2C%20Abu%20Bakr%2C%20and%20backed%20the%20Prophet%27s%20cousin%20and%20son%2Din%2Dlaw%2C%20Ali%2C%20as%20Islam%27s%20legitimate

[15] https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/the-history-of-the-muezzin–74007#:~:text=Bilal%20started%20the,worn%20down%20over

[16] https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/the-history-of-the-muezzin–74007#:~:text=These%20were%20built%20in%20Edirne%20and%20Istanbul%20at%20the%20command%20of%20the%20sultan%20of%20the%20time.%20The%20four%20minarets%20at%20the%20Selimiye%20Mosque%20in%20Edirne%20are%20among%20the%20slimmest%20and%20highest%20ever%20built%20and%20have%20three%20balconies.%20The%20Sultan%20Ahmed%20Mosque%20in%20Istanbul%20has%20an%20unconventional%20six.

[17] https://www.learnreligions.com/what-do-the-words-of-the-adhan-mean-in-english-2003812#:~:text=Muezzins%20with%20exceptionally%20beautiful%20voices%20sometimes%20achieve%20minor%20celebrity%20status%2C%20with%20worshipers%20traveling%20great%20distances%20to%20their%20mosques%20in%20order%20to%20hear%20their%20renditions%20of%20the%20adhan.

[18] https://www.bing.com/search?q=Zanzibaris+in+South+Africa+history&cvid=59486ac8bbfb4c5eab9632fa9d0ec947&aqs=edge..69i57.15106j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=Date-,The%20Zanzibaris%20were%20first%20classified%20by%20the%20South%20African%20Government,they%20have%20always%20had%20their%20roots%20in%20the%20African%20continent.,-History%20of%20Muslims

[20] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=The%20history%20of,Africa%20and%20Mozambique.

[21] https://www.bing.com/search?q=Kings+Rest+Bluff+Durban&qs=n&form=QBRE&msbsrank=0_1__0&sp=-1&pq=kings+rest+bluff+durban&sc=1-23&sk=&cvid=55085F4BCAAB477F888D551BFC29FB53#:~:text=Bluff%2C%20Durban%20(1.2%20miles%20from%20Kings%20Rest%20Railway%20Station)%20Located%20in%20quiet%20suburb%20in%20Durban%20south%20of%20the%20harbor%2C%20At%20the%20Sea%27s%20Edge%20features%20a%20terraced%20garden%20overlooking%20the%20sea.%20Free%20private

[22] https://www.google.com/search?q=Zanzibaris+in+South+Africa&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Zanzibaris+in+South+Africa&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i60.10500j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=South%20Africa%27s%20tight,lucrative%20tourist%20market.

[23] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%207,Indian%20Ocean%20slave%20trade.

[24] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%2026%E2%80%9354.

[25] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%2026%E2%80%9354.

[26] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=The%20Catholic%20mission%20of%20St%20Francis%20Xavier%20established%20a%20station%20in%20Inanda%20to%20the%20northwest%20of%20Durban%2C%20and%20an%20important%20school%20on%20the%20Bluff%20where%20significant%20numbers%20of%20both%20Catholic%20and%20Muslim%20Zanzibaris%20were%20educated.%20Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%2029%E2%80%9334%3B%20Oosthuizen%2C%20The%20Muslim%20Zanzibaris%2C%2013%E2%80%9318.

[27] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=The%20Catholic%20mission%20of%20St%20Francis%20Xavier%20established%20a%20station%20in%20Inanda%20to%20the%20northwest%20of%20Durban%2C%20and%20an%20important%20school%20on%20the%20Bluff%20where%20significant%20numbers%20of%20both%20Catholic%20and%20Muslim%20Zanzibaris%20were%20educated.%20Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%2029%E2%80%9334%3B%20Oosthuizen%2C%20The%20Muslim%20Zanzibaris%2C%2013%E2%80%9318.

[28] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%2036.

[29] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Ibid.%2037.%20It%20is%20likely%2C%20however%2C%20that%20the%20language%20Fakiri%20claimed%20to%20be%20Swahili%20was%20in%20fact%20Makua%2C%20and%20that%20such%20representations%20of%20Makua%20as%20Swahili%20were%20not%20uncommon%20among%20Zanzibaris.%20Ibid.%2072%E2%80%933.

[30] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Seedat%2C%20%E2%80%98The%20Zanzibaris%E2%80%99%2C%20253%E2%80%9382.

[31] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=A%20Zanzibari%20elder%2C%20Yussuf,Durban%2C%2028%20June%202010.

[32] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Boyer%2DRossol%2C%20K.%2C%20%E2%80%98De%20Morima%20%C3%A0%20Morondava%3A%20contribution%20%C3%A0%20l%E2%80%99%C3%A9tude%20des%20makoa%20de%20l%27ouest%20de%20Madagascar%20au%20XIXe%20si%C3%A8cle%E2%80%99%2C%20in%20Nativel%2C%20D.%20et%20Rajaonah%2C%20F.%20V.%20(eds.)%2C%20Madagascar%20et%20l%27Afrique%3A%20Entre%20identit%C3%A9%20insulaire%20et%20appartenances%20historiques%20(Paris%2C%202007)%2C%20192Google%20Scholar.

[33] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=N.%2DJ.%20Gueunier,93%E2%80%93122CrossRefGoogle%20Scholar.

[34] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Interviews%20with%20Salim%20Rapentha%2C%20Bayview%2C%2010%20Feb.%202009%2C%2012%20Feb.%202010%2C%20and%2015%20Feb.%202011.

[35] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Oosthuizen%2C%20The%20Muslim%20Zanzibaris%2C%2033%20and%2050.

[36] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Vahed%2C%20%E2%80%98Contesting%20%E2%80%9Corthodoxy,2007)Google%20Scholar.

[37] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Green%2C%20N.%2C%20%E2%80%98Saints,1999)Google%20Scholar.

[38] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Bang%2C%20Sufis%20and,2014)Google%20Scholar.

[39] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=These%20include%20the%20Badsha%20Piri%20shrine%20and%20burial%20site%20in%20Durban%27s%20central%20business%20district%2C%20next%20to%20the%20Victoria%20Market%20and%20the%20highly%20prosperous%20Sufi%20Sahib%20centre%20at%20Riverside%20on%20the%20Umgeni%20River%2C%20established%20in%201896.%20See%20the%20latter%27s%20web%20site%20at%20(http%3A//www.soofie.saheb.org.za/riverside.htm).

[41] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/zanzibaris-or-amakhuwa-sufi-networks-in-south-africa-mozambique-and-the-indian-ocean/894A07DDF7EDE7C1754B0CD1D95805E7#:~:text=Bangstad%2C%20%E2%80%98Diasporic%20consciousness%E2%80%99%2C%2032%E2%80%9360%3B%20Jappie%2C%20%E2%80%98From%20the%20madrasah%20to%20the%20museum%E2%80%99%2C%20369%E2%80%9399%3B%20Kaarsholm%2C%20%E2%80%98Diaspora%20or%20transnational%20citizens%E2%80%99%2C%20454%E2%80%9366.

[43] https://www.facebook.com/public/Balala-Sheik

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medina

[45] https://www.musjidussalaam.co.za/home/

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Azaan, History, Islam, Kaaba, Muezzin, Muslims, Peace, Religion, Spirituality, Tradition, Zanzibar

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 29 Nov 2021.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Muezzin’s Call, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.